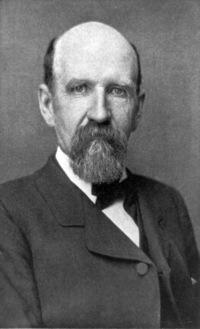

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SLOCUM, JOSHUA, sailor and author; b. 20 Feb. 1844 in Mount Hanly, N.S., son of John Slocum and Sarah Jane Southern; m. first 31 Jan. 1871 Virginia Albertina Walker (d. 1884) in Sydney (Australia), and they had seven children; m. secondly 22 Feb. 1886 his first cousin Henrietta Miller Elliot in Boston; they had no children; d. on or shortly after 14 Nov. 1909 in the Atlantic Ocean.

Joshua Slocum’s ancestors were loyalists from Massachusetts. When he was eight his family moved to the extreme western tip of Nova Scotia; his formal education ended two years later. Although his father worked on land, the males on both sides of his family had traditionally been seamen. Joshua was a cook on a local fishing boat for a while. In 1860, shortly after his mother died, he went to sea.

A year later Slocum was in the Pacific, where he would spend most of the next 23 years, developing into an accomplished sailor and navigator. About 1869 he became an American citizen. In 1875 he built a ship in the Philippines and was paid with a small ship, the first he owned. He gathered a crew to fish off Siberia; his wife Virginia, pregnant with twins, and their three children came with him. Slocum moved to larger ships twice, and remembered the second, the Northern Light, as the “finest American sailing-vessel afloat.” But the age of sail was ending. In early 1884 Northern Light needed repairs that economic conditions could not justify and so became a coal barge. Slocum’s career was in its twilight.

Slocum bought a new ship, the Aquidneck, which he later claimed was “nearest to perfection of beauty,” and took it to South America. There Virginia died. His sons believed that he never recovered from the shock. Two years later, however, he remarried, and after six days sailed with his new wife and two of his sons to South America. At the end of 1887, following many troubles, the uninsured Aquidneck was lost on a sand bar. Slocum and his family built the Liberdade from local materials and sailed it to Washington, where the vessel was exhibited at the Smithsonian Institution. Slocum wrote a book about the adventure, which he published and sold himself, without much success. No ships were subsequently offered to him. For a while he was employed in a Boston shipyard; his wife worked as a seamstress. In 1892 an acquaintance gave him an old sloop, the Spray, which he completely rebuilt and used for an unsuccessful fishing season in 1894. He was middleaged and groping for a living. The world saw no value in his sailing skills.

In response Slocum decided to celebrate those skills by sailing alone around the world, which no one had done. He left Boston in the Spray on 24 April 1895. He returned to Nova Scotia for the first time in 35 years to visit childhood friends, and in Yarmouth he bought the one-handed clock he called his navigational chronometer. The joke hid his skills as a navigator, including his ability to find longitude by complex calculations from lunar observations. It also concealed his spirituality; lunar navigation for him was “reading the clock aloft by the Great Architect.” He crossed the Atlantic to Gibraltar, where, daunted by stories of Mediterranean and Red Sea pirates, he changed direction and headed southwest towards Cape Horn, visiting Virginia’s grave en route. At the end of the Americas, where the Atlantic and Pacific collide to form the most dangerous sea in the world, Slocum had “the greatest sea adventure of my life.” After completing the difficult 400-mile passage through the Strait of Magellan, he was driven by a storm for four days towards Cape Horn. He thought, mistakenly, that he had rounded it, and headed north towards one of the greatest death-traps in the oceans, the shallow entrance to Cockburn Channel. In freezing darkness and fierce squalls he struggled to stand off it, and with daylight worked north into the Strait of Magellan to retrace his route into the Pacific.

Sailing westward, Slocum, a passionate reader, stopped at islands of literary significance to him: Más a Tierra (Isla Róbinson Crusoe), where Alexander Selkirk, the inspiration for Robinson Crusoe, had been stranded; and Upolu (Western Samoa), where he visited the widow of writer Robert Louis Stevenson. He arrived in Australia on 1 Oct. 1896. Word of his voyage had preceded him, and he was received with curiosity and honour. He gave newspaper interviews, raised money by giving tours of his boat, accepted hospitality, saw Virginia’s relatives, and waited for the season to change. Slocum left Australia on 24 June 1897 and passed to southern Africa. By now his exploit was famous, and the explorer Henry Morton Stanley and the Boer leader Paul Kruger both received him. From the Cape of Good Hope he re-entered the Atlantic and arrived in Newport, R.I., on 27 June 1898 after a voyage of 46,000 miles. He proclaimed himself healthier, happier, and younger than when he left.

The trip had been a step into unimaginable isolation. And yet in a sense Slocum was never fully alone. He befriended a spider on Spray; turtles, porpoises, and sea lions listened to his songs; when he was sick, the pilot of Columbus’s Pinta guided Spray. Although he does not seem to have been particularly Christian, he was respectfully sympathetic to all religions, and he felt the sacred in many things at sea. He withdrew from the human world and made the ocean his country.

The American public reacted with curiosity and scepticism to Slocum’s voyage. His serialized account of it, which appeared during 1899 and 1900, was a popular success, as was his book, Sailing alone around the world (New York, 1900). Lectures and the book’s royalties gave Slocum an income, and he bought a farm with his wife. But he was not a landsman; he drifted back to Spray and began spending winters in the West Indies. When in New Jersey to lecture to a yacht-club in 1906 he was charged with raping a 12-year-old girl, and after 42 days in jail did not dispute a reduced charge of indecent assault. He became more withdrawn from humanity. On 14 Nov. 1909 he sailed for the south from Massachusetts and was never heard from again.

[Nova Scotians claim Slocum as one of their own. A monument to him was unveiled at Westport in 1961; press articles about him appear with increasing frequency; and his book about his world voyage was adapted for radio in 1984. His defiance of a changing world, once seen as an oddity or a nuisance, is now as honoured as his seamanship.

Joshua Slocum is the author of three books on his life at sea; the first two, Voyage of the “Liberdade” ; description of a voyage “down to the sea” (1890) and Voyage of the “Destroyer” from New York to Brazil (1894), were privately issued at Boston. A publisher’s edition of Voyage of the “Liberdade” which omitted some appended material appeared there in 1894, and has been reprinted (New York, 1967). “Sailing alone around the world” first appeared in monthly instalments in Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine (New York and London), September 1899–March 1900, and was then published in monograph form (New York, 1900). It has since gone through numerous reprintings and subsequent editions, as well as several translations.

The full texts of Slocum’s books, including the appendices to the 1890 Voyage of the “Liberdade”, and many of his letters are available in The voyages of Joshua Slocum, a new edition prepared by Walter Magnes Teller (New Brunswick, N.J., 1958; 2nd ed., Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., 1985).

Archival sources on Slocum are relatively few and are scattered. Whatever papers he had were lost with Spray. His early life was documented by his eldest son in Victor Slocum, Capt. Joshua Slocum: the life and voyages of America’s best known sailor (New York, 1950; repr. Homewell, Eng., 1981), a British edition of which was published under the title The life and voyages of Captain Joshua Slocum (London, 1952). In The voyages of Joshua Slocum, Teller provides a note on sources; additional documentation appears in his preliminary biography, The search for Captain Slocum, a biography (New York, 1956), and in the extensively revised and augmented version of it, Joshua Slocum (New Brunswick, 1971).

The main holdings in public institutions are in the United States. There is also material in the Mitchell Library, Sydney, Australia. The holdings of the PANS are disappointing. The only material relating to Slocum is a few pages of research notes within the C. B. Fergusson papers at MG 1, 1846, F/3; however, the genealogical collection and clipping files contain some useful items. There are also some relevant clippings and notes in the Arch. files of the Yarmouth County Museum and Hist. Research Library, Yarmouth, N.S., including an account of Slocum’s visit from the 29 Sept. 1897 issue of the Planters & Commercial Gazette of Port Louis, Mauritius.

A fictionalized “autobiography” of Slocum by Robert Blondin, 7° de solitude ouest: autobiographie apocryphe reconstituée à partir de souvenirs recueillis au grenier de la légende volontaire du héros, was published in Montreal in 1989, and is now available in an English translation, The solitary Slocum (Halifax, 1992).

Modern solo sailors have taken Slocum as their inspiration and their teacher. However, they have yachts that are products of a technologically advanced society, are sponsored, and are linked to supporters at home by radio. A good indication of the extent to which these sailors are no longer isolated is provided in Dan Chu and Bonnie Bell, “While Bill Pinkney sails the world alone, thousands of Chicago school kids are keeping him company,” People Weekly (Chicago), 26 Nov. 1990: 101–5. b.d.m.]

R. B. Powell, “First, solo trip around the world,” Chronicle-Herald (Halifax), 15 Aug. 1964: 9. Along the clipper way . . . , ed. Francis Chichester (London, 1966). D. B. Sharp, “Joshua Slocum – sailing master,” Nautical Quarterly (New York), no.3 (April 1978): 88–97. W. [M.] Teller, “The Canadian who sailed alone around the world,” Canadian Geographic (Ottawa), 100 (1980–81), no.3: 74–79.

© 1994–2024 University of Toronto/Université Laval

Image Gallery

Cite This Article

Brian D. Murphy, “SLOCUM, JOSHUA,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/slocum_joshua_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/slocum_joshua_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Brian D. Murphy |

| Title of Article: | SLOCUM, JOSHUA |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2024 |