Source: Link

JOBIN, LOUIS (baptized Louis-Jean-Baptiste), sculptor, statuary, gilder, and inventor; b. 26 Oct. 1845 in Saint-Raymond, Lower Canada, son of Jean-Baptiste Jobin, a farmer, and Luce Dion; m. c. 1869 Marie-Flore Marticotte, and they adopted a daughter named Éva; d. 11 March 1928 in Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, Que.

Louis Jobin was the first child born to Jean-Baptiste Jobin and Luce Dion, who had married in January 1845 in Pointe-aux-Trembles (Neuville), and then moved to Saint-Raymond in the Portneuf region. In 1847 the Jobins returned to Pointe-aux-Trembles but two years later they went to the village of Petit-Capsa (later part of Pont-Rouge). Little is known about Louis’s childhood and youth except that he received a fairly good education. When he was about 14 or 15 years old he began working with an uncle, a wood-carver living at Quebec who was employed in the shipbuilding industry.

In 1865 Jobin entered the workshop of François-Xavier Berlinguet*, a celebrated Quebec wood-carver. Since there was no art school, the only way of learning the trade at that time was through a traditional apprenticeship to a master artisan. In the course of this broad training, Jobin created liturgical furniture (the altars of Sainte-Marie in Beauce), figureheads, commercial signs, ornaments, British coats of arms, and other works, most of which have now disappeared. His natural talent ensured that he soon became known for both secular and religious statuary. His Self-portrait, a polychrome relief now in the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Hull, dates from this period.

After a three-year apprenticeship with Berlinguet, Jobin left for New York, where he honed his skills in carving signs and figureheads. For more than a year he was employed as a carver at a number of workshops in lower Manhattan. He was first taken on as an assistant by William Boulton, a marble carver from London, England, who specialized in statues to be used as signs for tobacconists’ shops. He then worked for some Germans, in all likelihood at the firm of Simon Strauss, who advertised himself as a “Carver of Figures for Segar Stores.” At both places Jobin turned to good account his talents as a rougher and carver of statues.

Early in 1870 Jobin moved to Rue Notre-Dame in Montreal, where a number of sculptors had their studios. According to the 1871 census, he lived with Marie-Flore Marticotte, his new 30-year-old wife, and Narcisse Jobin, his younger brother, who was then a carver’s apprentice. During his five years in Montreal, he worked for himself in his own shop. In order to meet the competition and build up his reputation, he had to accept all kinds of orders, but only a few examples of his work remain.

It was mainly because of the various markets for secular sculpture that Jobin was able to earn his living during his early days in Montreal. He produced numerous figureheads for a Captain MacNeil, including one for the vessel Chief Angus. He carved a number of signs, in relief or in the round, depicting animals (a Hanging sheep for a tailor) as well as life-size human figures (a Lawyer for a law office and a Sailor for a tobacco merchant). According to an advertisement first carried in La Minerve on 4 June 1870, he had on display statues to be used as garden ornaments or as signs for tobacco merchants (“Indians and little Negroes,” as he put it). In the field of religious art, Jobin’s creations ranged from cabinetwork (the altar of the church of Saint-Pierre-Apôtre in Montreal) to representational sculpture. Of the few reliefs he produced that have been traced, three date from this period: Apparition of Our Lady of Lourdes for the church at Sault-au-Recollet (Montreal), Holy Family for the Carmelite monastery in Montreal, and Good shepherd (now in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa). A few sculptures in the round also bear witness to his skill in statuary. It was in his Montreal workshop that he began to specialize in the production of religious statues. Given a declining demand for sculpture for vessels – due to the advent of the steamer and the metal ship – and keen competition in the field of religious statuary, Jobin eventually had a hard time making a living at his trade in Montreal. In the fall of 1875 he closed his workshop and moved to Quebec.

On arrival in the capital, Jobin went into partnership for a year with Charles Marcotte as “merchants and wood-carvers.” He lived at various addresses in Saint-Jean ward before settling in 1878 at the corner of Rue Burton and Rue de Claire-Fontaine, where he had a house built for himself. A fire on 8 June 1881 in that faubourg destroyed his workshop, but he reopened it the following year at the same place. For a year he also had a shop on Rue Saint-Jean, where he sold his statues. Jobin regularly worked outdoors, attracting both passers-by and journalists. He hired assistants to produce furniture and ornamental work, in particular, and trained apprentices, including Henri Angers, who was with him from 1889 to 1893 and helped him create the monument to Saint Ignatius of Loyola for the Villa Manrèse at Quebec.

Jobin’s competitors included many local artists – amongst them wood-carver Jean-Baptiste Côté* and especially Italian sculptor and caster Michele Rigali* – but he also had to contend with imported items of foreign manufacture now on the market. He advertised regularly in Le Courrier du Canada (Quebec). These advertisements contain much information about the development of his career and work. At first Jobin offered a wide variety of statues and was ready to create, repair, or decorate altars, statues, and ornaments to order. Devoting himself increasingly to religious statuary “after the best European models,” Jobin began in 1881 to concentrate on what was to become his specialty: “lead-coated wooden statues for outdoor use” – figures sheeted in metal by a process of embossing and punching. In 1877 he displayed a Saint Joseph in the window of Le Courrier du Canada and three other statues at the Quebec provincial exhibition, at which he was awarded a “special prize.”

Religious statuary, then, proved Jobin’s most lucrative market. The artist found clients among the clergy, religious communities, architects active as contractors (Ferdinand Villeneuve*, David Ouellet*, Joseph-Ferdinand Peachy*), and ordinary citizens. While some fabriques, such as those of Saint-Charles parish (in the region of Bellechasse) and Sainte-Jeanne (in Pont-Rouge), purchased a good many statues at various times, others commissioned imposing decorative groupings to embellish the interior (32 statues for Saint-Henri, near Lévis, 1878–84; 17 statues for Saint-Patrice, in Rivière-du-Loup, 1894–95) or the exterior (six statues for Saint-Thomas in Montmagny, 1890). In 1894 Jobin delivered eight statues for the high altar in the church of Saint-Michel (Saint-Michel-de-Bellechasse). In 1894 and 1895 he produced 16 busts for the Séminaire de Québec. These imposing ensembles are among his most noteworthy religious works. Closely linked to the major devotions, which were themselves widely disseminated by contemporary popular imagery (the Sacred Heart, the Virgin Mary, St Joseph, St Anne, Calvary, and patron saints and angels of all kinds), many religious statues were also commissioned by individuals for diverse purposes such as thanksgiving, protection, or commemoration. A notable example was his Our Lady of the Saguenay, a huge 7.5-metre ex-voto created in 1880–81 for commercial traveller Charles-Napoléon Robitaille which was erected on Cap Trinité. Its history is truly an epic. Jobin also became renowned as an expert carver of Christ on the Cross and calvaries. He even received a commission from New Brunswick (a Calvary with six human figures for Richibucto, 1879–84). On the whole, the statues Jobin produced, which were dictated by the tastes and needs of his clients, bore a strong resemblance to the mass-produced plasters of his competitors. With his Our Lady of the Saguenay, however, he began to concentrate on the new market for large-scale, metal-clad outdoor statuary (Saint Louis, for the church of Lotbinière in 1888). Jobin’s reputation in this field even brought him some orders from the United States; the Brothers of the Christian Schools in 1889 purchased a Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle for their school in Ammendale, Md.

Despite this increasing specialization, Jobin still turned out sculpture for vessels and carved signs (figures of Amerindians and of all kinds of animals), designed liturgical furniture (altars at Cap-Chat in 1885 and Pointe-aux-Trembles in 1886), and supervised woodworking and ornamentation (interior decoration for the chapel of the Hôtel-Dieu du Sacré-Cœur de Jésus at Quebec, 1879). He also produced a few unusual works, such as a carved Coleoptera for naturalist Léon Provancher*, and in 1894 he invented a device for opening and closing the slats of window blinds without opening the windows. For the Saint-Jean-Baptiste festivities at Quebec in 1880, he helped create at least two banners and four floats bearing statues, including the one representing agriculture, which featured a Ceres (now in the Musée du Québec at Quebec). During the first winter carnivals in the capital, in 1894 and 1896, Jobin carved a few ice sculptures, including a replica of the Statue of Liberty, thereby becoming a pioneer in this technique in the province. In the spring of 1896 his studio again burned down. He sold his house and moved, penniless, to Sainte-Anne-de Beaupré, one of the most famous places of pilgrimage in North America. There he would carry out a number of commissions for the basilica and build up his religious clientele.

At first Jobin lived in a small dwelling adjoining a workshop, but in 1901 he bought a lot on Chemin Royal and had a house built there. He set up his new shop in the basement and decorated the exterior with numerous statues. He again hired a few apprentices and assistants. In 1901, to complete the interior decor of Saint-Louis-de-l’Isle-aux-Coudres (including the retable, high altar, and side altar), he hired Régis Perron, a local carpenter who would later follow the master artisan to Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré. In 1907, after the death of his wife, Jobin took in his nephew, Édouard Marcotte, who would become his chief assistant, as well as an eccentric inventor and sculptor named Octave Morel, who would later die in his house.

At the beginning of his stay in Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, Jobin again gave his attention to church ornamentation and to making liturgical furniture. Around 1898, for example, the sculptor created various works in the old basilica of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré (among other things, altars and ornaments for the side chapels and canopies for the episcopal thrones). In the secular field, he would produce only five more statues: a Neptune and a Wolfe for two commercial buildings at Quebec (1901), a bust of Champlain for the capital’s tercentenary (1908), and a Frontenac and a Lord Elgin for the Séminaire Saint-Charles-Borromée in Sherbrooke (1913). By specializing in statues “overlaid with metal, impervious to seasonal inclement weather,” Jobin held pride of place, as a wood-carver, in the market for exterior religious and monumental statuary. Designed to stand in the open air, his works imitated, moreover, the bronzes of his competitors. The sculptor’s last two account books, which cover the years 1913–25, list some 240 commissions for religious statues, for the most part of considerable size. In this period, and especially during World War I, he would become the Quebec specialist in monuments to the Sacred Heart and in calvaries with one, three, or six human figures (Ermitage San’Tonio at Lac-Bouchette, 1918), themes which were often commissioned as ex-votos and which would constitute 40 per cent of his output.

At Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré Jobin acquired a significantly larger and more diverse clientele. He became the leading supplier of religious statues for architect-contractors, for retailers of religious articles, and even for other sculptors, such as Louis Caron of Nicolet, Joseph Villeneuve and Joseph Saint-Hilaire of Saint-Romuald, and François-Pierre Gauvin of Quebec. Several fabriques (Saint-Georges-de-Windsor and Sainte-Perpétue in the Nicolet region; Chute-à-Blondeau and St-Eugène in Ontario) and religious communities (Redemptorists and Franciscan Missionaries of Mary in Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré) also purchased a number of works. Jobin created a dozen groupings, consisting of three to five statues each, to decorate church façades (Saint-Casimir in the Portneuf region in 1899, and Saint-Dominique in Jonquière in 1913). Living very close to the railway, Jobin also shipped many works to tourists and pilgrims who came from all over Canada and even from the United States.

Jobin’s everyday work at Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré is generally of rather average quality because of technical and aesthetic factors, but also due to the modest price of the statues and the short time allowed for completion of a large number of works. When the client agreed to pay their true value, however, the sculptor succeeded in executing exceptional works. Three illustrations are: the recumbent statue of Saint Anthony of Padua in the chapel of the Hôtel-Dieu Saint-Vallier in Chicoutimi (1900), with its unusual subject and model; the Angel with trumpet on the organ case of the church in Plessisville (1902), a masterpiece of delicacy and elegance; and the equestrian monument of Saint George slaying the dragon for the parish of Saint-Georges in Beauce (1909), the most complex work the artist ever created.

There was a marked decline in Jobin’s output around 1920, when he reached the age of 75. At the same time a number of prominent people rediscovered “the old sculptor on the Beaupré shore,” and their accounts, while invaluable, depict the artist sometimes as an exotic or folk figure, sometimes as a romantic and legendary one. They included journalist Victoria Hayward and photographer Edith S. Watson; writer Frank Oliver Call; painter John Young Johnstone; ethnographer Marius Barbeau* of the Victoria Memorial Museum in Ottawa (which in 1927 became the National Museum of Canada), accompanied by two painters from the Group of Seven, Arthur Lismer* and Alexander Young Jackson*; and writer and journalist Damase Potvin*. At the end of 1925, after shipping one final work to Florida, the sculptor gave all his property, including his statues and tools, to his nephew, and retired. It was only then that museums and collectors began to purchase his sculptures and that the first exhibits of his works were held at the Art Gallery of Toronto (Art Gallery of Ontario) and the Château Frontenac at Quebec. On 11 March 1928 the artist died in poverty but famous because of the many articles about him published in newspapers in Quebec and in English Canada during the 1920s.

More than any other sculptor of his day, Louis Jobin demonstrated an unusual adaptability and sensitivity to the needs of his milieu and the dictates of the marketplace, which was shaped by pressures of competition and of nascent industrialization. In the province of Quebec, he was one of the most famous and prolific sculptors of his time and he is now considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of this art. During his 60-year career he produced at least 1,000 sculptures, which are now to be found across North America. Despite his traditional and non-academic background, he is seen as a fully-fledged artist. When he was living at Quebec, he was from the outset the sculptor favoured by the press, and columnists never stopped praising his talent and his creations. Some of his works, such as the Our Lady of the Saguenay, are real technical feats. Others, such as the statues at Saint-Henri and Saint-Patrice, are among the masterpieces of early sculpture in Quebec. Spanning the 19th and 20th centuries and linking the traditional and the modern, the career and output of Louis Jobin stand as a milestone in the evolution of Quebec sculpture.

[Louis Jobin was the subject of a major retrospective at the Musée du Québec during the summer of 1986. The exhibition was accompanied by the publication of a monograph by Mario Béland entitled, Louis Jobin, master sculptor (Québec, 1986). Of its 210 illustrations, 59 present a selection of Jobin’s sculptures and another 59 concern his studio pieces, his tools, and other items. The work contains a historical essay, a chronological summary, a list of exhibitions, and a bibliography. Also valuable are Mario Béland, “Les trente premières années du sculpteur Louis Jobin (1845–1928): formation et premier atelier” (mémoire de ma, univ. Laval, Québec, 1984), and especially the same author’s “Louis Jobin (1845–1928) et le marché de la sculpture au Québec” (thèse de phd, univ. Laval, 1991). The doctoral disseration includes a detailed chronology and an exhaustive bibliography divided into several sections: archives and manuscript sources, printed sources, reference works and research guides, specialized publications, and newspaper and journal articles. In addition it contains four appendices: references to Louis Jobin in the Quebec and Montreal directories between 1860 and 1896; announcements in La Minerve (Montréal), from 4 June to 7 Sept. 1870 and Le Courrier du Canada (Québec) between 5 May 1876 and 30 Jan. 1896; order-books (1913–26); and 12 extracts from various journals (1873–1900).

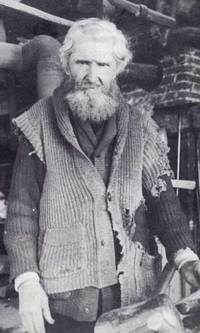

Examples of Jobin’s work are to be found in most art galleries in Quebec and Ontario. There are numerous photographic portraits of him, taken at different periods, as well as sketches drawn by Arthur Lismer in 1925 and a canvas painted by John Young Johnstone around 1920. Most of these images show the sculptor working in his studio or posing beside his statues.

Despite intensive research, the place and date of Jobin’s marriage have not been identified. His baptismal record is available at ANQ-Q, CE301-S53, 4 déc. 1845. Given the extensive bibliography provided in the author’s thesis, only a few additional publications issued since 1991 are cited here: Mario Béland, “Les monuments de bois: ces autres disparus,” Continuité (Québec), 49 (1991): 33–37, and “Aux origines de la sculpture sur glace,” Continuité, 59 (1994): 18–20; and Karel, Dict. des artistes.] m.b.

© 2005–2024 University of Toronto/Université Laval

Image Gallery

![Original title: DescriptionLouis Jobin dans son atelier 1926.jpg Français : Le sculpteur Louis Jobin dans son atelier, à coté d'une sculpture de la Vierge et l'enfant Jésus. Date 1926 Source [1] Author Frank Oliver Call](/bioimages/h100.7102.jpg)

Cite This Article

Mario Béland, “JOBIN, LOUIS (baptized Louis-Jean-Baptiste),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 16, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jobin_louis_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jobin_louis_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mario Béland |

| Title of Article: | JOBIN, LOUIS (baptized Louis-Jean-Baptiste) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 16, 2024 |