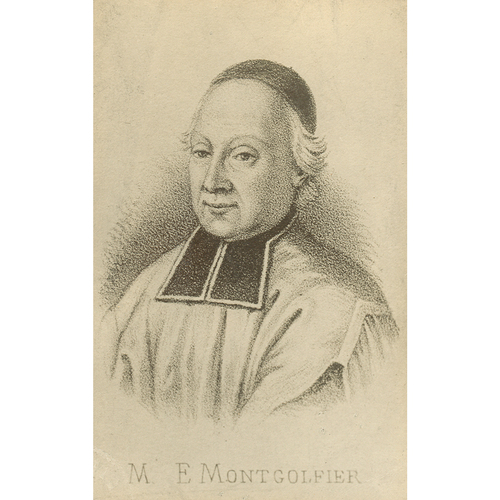

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MONTGOLFIER, ÉTIENNE, priest, superior of the Sulpicians in Montreal, and vicar general; b. 24 Dec. 1712 at Vidalon (dept of Ardèche), France, son of Raymond Montgolfier, and uncle of Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne de Montgolfier, the famous inventors of the balloon; d. 27 Aug. 1791 in Montreal (Que.).

Having chosen the priesthood when he was 20, Étienne Montgolfier entered the diocesan seminary in Viviers, France, where he undertook classical studies and courses in philosophy and theology. Ordained priest on 23 Sept. 1741, he obtained his bishop’s permission to join the Sulpicians. He went to Issy-les-Moulineaux to spend his year of seclusion (the equivalent of a noviciate). During the next nine years he taught theology in various Sulpician seminaries in France. In compliance with a request from his superior general, Jean Couturier, he left La Rochelle on 3 May 1751 to join the Sulpicians in Montreal, where he arrived in October.

Montgolfier soon gained a natural authority over the Sulpicians in Montreal. In January 1759 he was named superior, replacing Louis Normant* Du Faradon. This title automatically conferred on him the duties of administrator of the seigneuries belonging to the Sulpicians, titular priest of the parish of Montreal, and vicar general of the bishop of Quebec for the District of Montreal; he gave up this last office in 1764. No superior ever held office under such difficult circumstances. Quebec had just surrendered to the British, Bishop Pontbriand [Dubreil*] took refuge at the Sulpician seminary only to die there on 8 June 1760, and Montreal surrendered to the enemy on 8 September. Major-General Amherst, however, left the Canadians free to practise the Catholic faith, and Montgolfier was able to remain in contact with the vicar general of Quebec, Jean-Olivier Briand, who following the bishop’s death was considered to be the “first vicar general.”

After the ratification of the transfer of Canada by France to Great Britain, Montgolfier decided to go to Europe, initially to see his superior general in France, and then to meet with the British government in London. His objective was to secure the Sulpicians’ enjoyment of their property by getting the Sulpicians in France to relinquish it in their favour, and by keeping his group from being identified as a religious community like the Recollets or Jesuits. In this way the Sulpicians were to avoid being despoiled by the new colonial government.

On the occasion of the trip which he undertook in October 1763, Montgolfier had also been entrusted by the chapter of Quebec with the task of working for the appointment of a new bishop in North America. Putting forward the ancient right by which they were to elect a new bishop when the see was vacant, the canons had made the customary arrangements on the preceding 15 September: a mass of the Holy Spirit, a swearing-in of electors, and an election. They had confided to the Sulpician superior the name of the person whom they wanted for bishop – Montgolfier himself. The election was deemed null and void by the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda, because from the time the provisions of the Council of Trent (1545–63) had come into force the choice of bishops had rested with the pope, even though his choice might be made from among candidates put forward by other bishops or even, as in the present circumstances, by the canons. Pope Clement XIII indeed accepted the canons’ choice of Montgolfier, and no one in Rome, Paris, or London was opposed to it. However, before the date set for his consecration, June 1764, Montgolfier learned that the governor general of Canada, Murray, preferred Canon Briand. The Sulpician did not insist; he returned to Canada and gave his resignation as bishop elect to the chapter of Quebec. After Briand had become bishop in 1766, he appointed Montgolfier second vicar general of Montreal, in order to ease the burden on Étienne Marchand.

Later Montgolfier took part in an attempt to set up a bishopric in Montreal. Briand and his coadjutor, Louis-Philippe Mariauchau d’Esgly, seldom went to Montreal, mainly – because of their advanced age and the primitive state of transportation at the period. The population of Montreal was growing rapidly, however, and the need for a bishop was being felt. Consequently two Canadian delegates were chosen to go to London bearing a memoir drawn up with Montgolfier’s help which advocated the creation of an episcopal see in Montreal and the coming to Canada of French speaking priests from Europe. Jean-Baptiste-Amable Adhémar and Jean De Lisle* de La Cailleterie went to London in 1783, but they found it difficult enough to pursue the second objective and confined themselves to it. When Briand resigned the following year and the question of appointing a coadjutor for d’Esgly arose, both of these men, along with Governor Haldimand, thought of Montgolfier, but in July 1785 the latter indicated his unwillingness. He felt that he was too old and he preferred to continue directing his efforts to having French Sulpicians come to Montreal.

Meanwhile Montgolfier had found himself obliged to take a stand on various political occasions in Canada. Opportunities to do so were not lacking. There was, for example, the incident on 7 Oct. 1773 on the occasion of the erection in Montreal’s Place d’Armes of a monument of thanksgiving to George III. Montgolfier had not been invited to be present, and not being in the habit of taking part in military or civil ceremonies, he remained in the Sulpician house. Luc de La Corne suggested to the military commander that church bells should be rung to accompany the artillery salvoes. The officer did not object, but Montgolfier, the ecclesiastical superior, who was approached three times by La Corne, retorted: “You know we consider our bells as instruments of religion that have never been used in military or civil ceremonies.” He finally added, when pressed by his importunate visitor: “If the commandant demands that the bells be rung, he is free to order the beadle, and I shall have nothing to say.” The commandant, in fact, was less insistent than La Corne, and the bells did not peal.

The invasion of Quebec by Americans [see Richard Montgomery] led to Montgolfier’s taking more significant action. At Bishop Briand’s request, the Sulpician prepared an outline of an appropriate sermon and distributed it to parish priests in the District of Montreal. In order to counteract American propaganda he elaborated in the sermon four points to prove the importance of supporting the British government: as a patriot, the Canadian must defend his country against the invaders; as a subject, a citizen who has taken an oath of loyalty to the king is violating the law if he refuses to obey orders; as a Catholic, the Canadian must show that his religion teaches him to obey his sovereign; finally, Canadians have a debt of gratitude towards the king, who has treated them well, and towards Governor Guy Carleton*, who has defended their cause in London. Montgolfier concluded his model sermon with a reminder of what had happened to the Acadians some 20 years earlier [see Charles Lawrence*]; was it not wiser to choose the established power?

His correspondence with Bishop Briand reveals that Montgolfier was well informed of the comings and goings of the American rebel forces and the British soldiers. Carleton’s presence in Montreal in 1775 prompted the Indians and certain French speaking whites to take a stand; having been neutral, they now came out in favour of the king. At the same time, moreover, Montgolfier wrote a circular letter to all the parishes in his district, supporting Carleton’s decision to re-establish the militia units. During the period the Americans were in Montreal, from November 1775 to the spring of 1776, Montgolfier avoided relations with them; he considered them rebels and had difficulty understanding the neutrality of most Canadians. Once the town had been liberated, he expressed appreciation that tranquillity had been restored through “the protection of an equitable government; integrity is respected, and virtue protected.” He assured Briand that parish priests were admitting to the holy sacraments only those of the pro-Americans who had recognized their error and had recanted in public through word or deed. A small number, however, refused to accept these conditions. For their part, the clergy seemed to be completely submissive to the legitimate authority, with the exception of Jesuits Joseph Huguet, a missionary at Sault-Saint-Louis (Caughnawaga), and Pierre-René Floquet, the priest in charge at Montreal, and Sulpician Pierre Huet* de La Valinière, parish priest at L’Assomption.

The other stands taken by Montgolfier were in particular cases usually related to his office as vicar general: approval or refusal of marriages between Catholics and Anglicans, recruiting and training of candidates for the priesthood, restoration of the old chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours which had been destroyed by fire in 1775, a new printing of the shorter and longer catechisms, the appointment of priests, the possibility of holding Church of England services in certain Catholic churches. These subjects were dealt with in his correspondence with the bishop of Quebec, who had the final responsibility for the decisions taken by his vicar general.

Montgolfier was also concerned about the influence in Montreal of the French philosophers of the Enlightenment. The first poem published in French in a North American newspaper, La Gazette de Québec/Quebec Gazette, was an epistle from Voltaire to a cardinal; in it he criticized the church’s intolerance and sectarianism. When the Académie de Montréal established its own official organ, La Gazette littéraire pour la ville et le district de Montréal, ten years later, in 1778, this paper praised Voltaire’s writings, thinking, and wit [see Fleury Mesplet]. Montgolfier asked Bishop Briand to intervene with the authorities in order that the harm might be checked. “Scorning it as it deserves, I had always hoped that this gazette would disappear by itself; but since it looked to me as if the government’s protection was being sought for it, I thought it opportune to anticipate events.” In any case, the newspaper had to be given up the following year, 1779. The academicians’ infatuation with the French encyclopaedists, and especially with Voltaire, had in truth done their cause harm, for the spirited replies of the readers ultimately had greater influence on the thinking of Canadians than had the academicians’ ill-chosen remarks.

At the end of his life Montgolfier was extremely concerned about a drop in the number of priests. His numerous efforts to bring Sulpicians or other priests from France were never rewarded by the hoped-for results. In the autumn of 1784 he tried to make contact with his superior general, Jacques-André Emery, through former Governor Carleton who was in England at that time: “Could you not send me someone reliable, chosen by yourself, to succeed me in the position I hold in Montreal, and have him accompanied by one or two equally reliable persons?” But Governor Haldimand insisted upon respecting the king’s instructions of 1764 which dictated that no Frenchman could come to Canada. Yet the Sulpicians were recruiting few Canadians, one among many reasons being to maintain a majority of Frenchmen within the group; the attitude was a hangover from colonialism. In any event, few Canadians had a calling to the priesthood at that period. Montgolfier, in short, reached the end of his life fearing that he would see the Sulpicians disappear from Canada. In 1787 he resigned from his double charge as ecclesiastical superior and chaplain to the Congregation of Notre-Dame, having just written La vie de la vénérable sœur Marguerite Bourgeois . . . , which was to be published in 1818. In 1789, his faculties failing and no longer able to read or write, he got his colleague Gabriel-Jean Brassier to assist him in his role as superior of the Sulpicians and vicar general to the bishop of Quebec. He died in Montreal on 27 Aug. 1791.

A dignified, affable, and well-mannered man, Montgolfier tried to collaborate as far as possible with the bishop of Quebec in the ecclesiastical organization of his adopted country. More a pragmatist than a thinker, more a jurist and canonist than a theologian, he wanted to ensure the survival of Catholicism in new and delicate circumstances. Had he been titular bishop, Montgolfier might have displayed his personality in more striking fashion, and he would in the process have become more Canadian. In fact, throughout his stay in Montreal he remained French, and he preserved a European turn of mind in the Sulpicians which made them feel closer to the new British masters than to the Canadian people.

[Étienne Montgolfier], La vie de la vénérable sœur Marguerite Bourgeois, dite du Saint-Sacrement, institutrice, fondatrice, et première supérieure des filles séculières de la Congrégation Notre-Dame, établie à Ville-Marie, dans l’isle de Montréal, en Canada, tirée de mémoires certains et la plupart originaux (Ville-Marie [Montréal], 1818).

ACAM, 901.005, 763-2, 766-4, 768-5, 768-6, 769-1, 769-5, 769-6, 771-2, 771-6, 773-2, 773-3, 773-6, 773-7, 775-11; 901.115, 776-3, 776-5, 777-2, 777-3, 777-6, 779-1, 779-2, 780-2, 780-7, 780-8, 780-9, 781-1, 781-4, 782-6, 782-7, 782-8, 782-9, 783-2, 783-4, 783-7. PRO, CO 42/16, ff.280–82. Mandements des évêques de Québec (Têtu et Gagnon), II, 265–66. Allaire, Dictionnaire. Louise Dechêne, “Inventaire des documents relatifs à l’histoire du Canada conservés dans les archives de la Compagnie de Saint-Sulpice à Paris,” ANQ Rapport, 1969, 149–288. Desrosiers, “Corr. de cinq vicaires généraux,” ANQ Rapport, 1947–48, 79–100. Gauthier, Sulpitiana (1926), 234–36. Lanctot, Le Canada et la Révolution américaine, 65. Lemieux, L’établissement de la première prov. eccl., 1–8, 18–23. M. Trudel, L’Église canadienne, I, 260–96. T.-M. Charland, “La mission de John Carroll au Canada en 1776 et l’interdit du P. Floquet,” SCHÉC Rapport, 1 (1933–34); 45–56. Séraphin Marion, “Le problème voltairien,” SCHÉC Rapport, 7 (1939–40), 27–41. É.-Z. Massicotte, “Un buste de George III à Montréal,” BRH, XXI (1915), 182–83. Henri Têtu, “L’abbé Pierre Huet de La Valinière, 1732–94,” BRH, X (1904), 129–44, 161–75.

Cite This Article

Lucien Lemieux, “MONTGOLFIER, ÉTIENNE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/montgolfier_etienne_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/montgolfier_etienne_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lucien Lemieux |

| Title of Article: | MONTGOLFIER, ÉTIENNE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | November 6, 2025 |