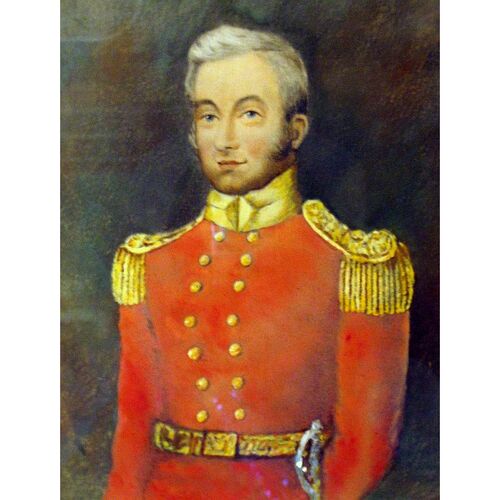

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DURNFORD, ELIAS WALKER, army officer and military engineer; b. 28 July 1774 in Lowestoft, England, son of Elias Durnford and Rebecca Walker; d. 8 March 1850 in Tunbridge Wells (Royal Tunbridge Wells), England.

Although he was born in Suffolk, on the North Sea coast, Elias Walker Durnford spent his first years in Pensacola (Fla), where his father was commanding engineer and then lieutenant governor of the British colony of West Florida. When he was about four, he went back to England without his parents, who entrusted him to the care of an aunt. After his father also returned on the conclusion of the American revolution, Elias, who wanted to become a military engineer himself, attended a preparatory school for the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich (London) and was subsequently admitted to the academy in October 1788. He was commissioned in the Royal Artillery in April 1793, at 18 years of age, and in October was promoted second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers. His first posting took him to the West Indies to serve alongside his father. In 1794 he directed the construction of defensive works for Pointe-à-Pitre in Guadeloupe, where he was subsequently taken prisoner by the French. After 17 months of captivity he was exchanged in July 1796 for a French officer. He resumed his engineering duties in England, and then in Ireland. When he was appointed in 1808 as commanding engineer in Newfoundland, he had to give up a “deep desire” to take part in the war in Spain.

In Newfoundland Durnford was primarily occupied with maintaining and building coastal batteries; he also put up a blockhouse on Signal Hill, near St John’s. In 1813 he became a major in the army and a lieutenant-colonel in the Royal Engineers, undertaking garrison duties in addition to his engineering responsibilities. He was also named aide-de-camp to the officer commanding the forces on the island. During his stay he obtained a grant of four acres on which he grew potatoes.

From 1816 to 1831 Durnford was commanding officer of the Royal Engineers in the Canadas. He lived at first in a rebuilt section of the former intendant’s palace at Quebec, and then moved with his family into the official residence for the commander of the Royal Engineers on Rue Saint-Louis. The construction of the Quebec citadel was undoubtedly his major accomplishment in British North America. The work substantially completed the town’s defensive system, but the classical plan he had chosen showed that the military had a constant fear of a popular uprising. At Quebec Durnford also was in charge of rebuilding the Palais gate as well as of repairing the Anglican Cathedral of the Holy Trinity. He coordinated the reorganization of the colonies’ defences to fit a new plan developed after the War of 1812 by the governor, the Duke of Richmond [Lennox*], and approved by the Duke of Wellington. A number of military works were built at that time, on Île Sainte-Hélène and Île aux Noix and at Kingston, Upper Canada, among other places. In addition, Durnford worked on the construction of canal systems on the Rideau and Ottawa rivers, although the Rideau Canal was built under his friend John By in the period 1826–31 and was never under his authority. In 1823 he had signed a voluminous report on the state of the fortifications and military buildings in the Canadas. He obtained the rank of colonel in the Royal Engineers in March 1825. As such he was granted his request, made to Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay], that he be appointed commander of the troops in Lower Canada while retaining his engineering post; to his chagrin, he had failed to obtain the command a few months earlier.

Durnford returned to England in 1831 and six years later was retired from service. In 1846 he obtained the supreme rank of colonel commandant in the engineers, and in the army he almost reached the top, since he was made a lieutenant-general.

Throughout his career Durnford displayed assiduity and exemplary honesty, and he apparently won the esteem of both colleagues and superiors. During the height of the construction season he visited work sites early in the morning and then busied himself in the engineers’ office until supper time, late in the evening. Eager to manage public funds with economy, he behaved irreproachably in the numerous transactions that he conducted in the name of the British government to purchase properties needed for the glacis of the Quebec citadel. Despite his zeal, he was not always beyond reproach. In 1825 the Board of Ordnance accused him of being lax in his administration of the Royal Engineers, in particular because of appointments and salary arrangements made without following the usual administrative procedures. Like most military engineers of the time Durnford did a poor job of calculating the building costs for military works. The case of the citadel is especially revealing: initially estimated at £72,400, the project cost the Treasury a little more than twice this sum.

Family values, along with professional principles, were of the greatest importance for Durnford. On 30 Oct. 1798 he married Jane Sophia Mann, daughter of a lawyer in Gravesend, England. They had 13 children, of whom four were born in Newfoundland and three at Quebec. Their six sons followed in Durnford’s footsteps to become officers in the British army. Three worked in turn with him as clerks in the office of the Royal Engineers at Quebec, and the eldest and the youngest joined the corps. The family followed him wherever he went, and two of his unmarried daughters remained with him even after he retired.

An ardent conservative, Durnford respected the traditional values of his station, although he did not much enjoy social gatherings. He engaged in several sports, including cricket. Whether in Newfoundland, the Canadas, or Tunbridge Wells, the village to which he retired, Durnford liked to relax by gardening and taking care of a few animals. He was fond of reading, as was his wife; he particularly enjoyed Hannah More’s religious and philanthropical works, which he bought for the Garrison Library at Quebec when he was its president.

It is difficult to estimate Durnford’s fortune. Certainly, his engineering officer’s pay, his post as officer commanding the Royal Engineers, and the various allowances to which he was entitled put him near the top of the British army’s pay structure. He regularly kept more than one servant, and sometimes three or four. His sons studied at private institutions in England, and he gave them allowances befitting their rank. Durnford also travelled a great deal. His father and one of his aunts had owned numerous lands in Florida and New Orleans which were confiscated as a result of the American revolution. He took various measures, even making a six-month trip to the United States in 1820 and going to court several times in 1838, but title had been lost and he was never able to profit from these holdings. It is not known whether he received money that had been left by his father for his mother’s use, but when her second husband died, he inherited £1,000 sterling.

Elias Walker Durnford’s career was centred mainly on administration and no important scientific contribution to military engineering came out it. The name Durnford remained famous in the Royal Engineers, however, through the ongoing presence for more than a century and a half of 11 members of the family. In addition to his father and two of his own sons, his brother Andrew and four of Andrew’s descendants, as well as two other Durnfords whose relationship is not known, all served in the corps. Through the descendants of a third son, Philip, the Durnford line still exists in Canada today.

Elias Walker Durnford began writing his autobiography but it was never finished. The first part was published in 1850, the year in which he died, as “Scenes in an officer’s early life at Martinique, Guadeloupe, &c., during the years 1794 & 1795, recalled in advanced years,” Colburn’s United Service Magazine (London), pt.ii: 605–14.

ANQ-Q, CE1-71, CN1-16, CN1-49. PAC, MG 24, F73; RG 8, I (C ser.), 393–441; II, 80–81. Private arch., E. A. Durnford (Montreal), Notes and docs. PRO, CO 42/136–200; WO 55/860–68. Family recollections of Lieut. General Elias Walker Durnford, a colonel commandant of the Corps of Royal Engineers, ed. Mary Durnford (Montreal, 1863). List of officers of the Royal Regiment of Artillery from the year 1716 to the year 1899 . . . , comp. John Kane and W. H. Askwith (4th ed., London, 1900). A. J. H. Richardson et al., Quebec City: architects, artisans and builders (Ottawa, 1984). Roll of officers of the Corps of Royal Engineers from 1660 to 1898 . . , ed. R. F. Edwards (Chatham, Eng., 1898). J. E. Candow, A structural and narrative history of Signal Hill National Historic Park and area to 1945 (Parks Canada, National Hist. Parks and Sites Branch, Manuscript report, no.348, Ottawa, 1979). Andre Charbonneau et al., Québec ville fortifiée, du XVIIe au XIXe siècle (Québec, 1982). Whitworth Porter et al., History of the Corps of Royal Engineers (9v. to date, London and Chatham, 1889– ; vols.1–3 repr. Chatham, 1951–54). J.-P. Proulx, Histoire de St-John’s et de Signal Hill (Parks Canada, National Hist. Parks and Sites Branch, Manuscript report, no.339, Ottawa, 1978). A. G. Durnford, “A unique record,” Royal Engineers Journal (Brompton, Eng.), [new ser.], 2 (1909).

Cite This Article

André Charbonneau, “DURNFORD, ELIAS WALKER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed October 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/durnford_elias_walker_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/durnford_elias_walker_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | André Charbonneau |

| Title of Article: | DURNFORD, ELIAS WALKER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | October 21, 2025 |