KERR, JAMES (until at least 1806 he signed Ker), lawyer, judge, and politician; b. 23 Aug. 1765 in Leith, Scotland, third son of Robert Kerr and Jean Murray; d. 5 May 1846 at Quebec.

James Kerr, the son of a prominent merchant in Leith, received his early education at a local grammar school. On 1 Sept. 1785 he was admitted to the Inner Temple, London. While pursuing his legal studies there he enrolled at the University of Glasgow, but he did not graduate. He was called to the bar, and in 1793 was practising on the London and Middlesex circuits. By the following year he was married. He and his wife, Margaret, would have at least seven children, two of whom would die in infancy.

To improve his prospects, Kerr immigrated to Lower Canada, and on 10 Aug. 1794 he received his commission as a lawyer. By 1795 or 1796 he was sufficiently well established to bring out his wife and children. On the voyage to England a French vessel captured his ship and he was taken prisoner. Soon exchanged, he rejoined his family and brought them to Lower Canada in 1797. In France he had acquired knowledge which was, in his own words, “deemed important.” As a reward for transmitting it to the British government he was appointed on 19 Aug. 1797 judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court of Lower Canada.

Kerr’s nomination permitted him to continue his legal practice. One of his most controversial cases was a defence of Clark Bentom*, charged in 1803 with illegally exercising the office of a minister. In reply to an inflammatory pamphlet written by Bentom, accusing Kerr of having deserted and betrayed him, Kerr published a vigorous rebuttal of Bentom’s “ill founded and malevolent censure.” On 1 July 1809, giving up his practice, Kerr was named a puisne judge of the Court of King’s Bench for the district of Quebec. He was appointed to the Executive Council on 8 Jan. 1812 and became, ex officio, a member of the Court of Appeals. During the absence of Chief Justice Jonathan Sewell from 1814 to 1816, Kerr presided over the Quebec Court of King’s Bench as senior judge and was president of the Court of Appeals.

By 1816 Kerr was living in a “neat,” well-furnished home, having a coach-house and stables for eight horses, in the faubourg Saint-Jean. The property demonstrated Kerr’s interest in horticulture since it contained a garden sown “with every vegetable suitable to the climate,” as well as gooseberry and currant bushes, vines, asparagus beds, and 90 fruit trees. After his wife’s death in 1816, he put his home up for rent or sale and left for Britain on personal business. He remarried in Scotland some time before his return in 1819, but his wife, Isabella, who was 25 years his junior, died at Quebec in 1821, leaving him with at least an infant son.

From 1819 to 1827 Kerr was among four executive councillors auditing the public accounts. Appointed to the Legislative Council on 21 Nov. 1823, he served occasionally as speaker during Sewell’s absences, particularly in 1827. Highly conscious of his status as a judge and office holder, Kerr seems to have spent beyond his means in order to maintain his position in society. In 1824 his debts totalled £3,227 16s. and his salaries of £1,333 were attached for the benefit of his creditors. One of their trustees, Mathew Bell, cautioned Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay] in 1825 that Kerr was “agreeable in society” but was not respected; “irregular in money transactions,” he was “indebted to his tradesmen & always in distress.” Despite an income of £1,400, plus fees, he was occasionally prosecuted in court for non-payment of debts.

In part as a result of his financial difficulties, from 1828 Kerr was embroiled in a series of disputes concerning his conduct, salary, and fees. Although characterized by a contemporary as “a thorough gentleman of the old school,” he was inclined to outbursts of temper, even in court. That year Bartholomew Conrad Augustus Gugy*, a proctor in the Vice-Admiralty Court whom Kerr had suspended for contempt of court, presented to the House of Assembly what Louis-Joseph Papineau* described as “the most acrimonious petition I have ever seen.” A committee was struck to examine Gugy’s 51 accusations; its work would drag on for several years. Meanwhile, in December 1828, the Committee of Trade at Quebec protested the rate and structure of Kerr’s fees as judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court, and even argued that by an ordinance of 1780 his salary had been set in lieu of them. At the same time the assembly voted Kerr’s salary on the condition that he not receive fees. In response to the assembly’s action Kerr argued that it created a dangerous precedent; the assembly could attach numerous conditions to its voting of the civil list, thus encroaching on the privileges of the Executive and the Legislative councils and creating a “French democracy.” However, Sir James Kempt*, who had succeeded Dalhousie in the administration of Lower Canada, ordered Kerr to forego fees if he wished to retain his salary, and Kempt’s decision was supported in 1831 by Colonial Secretary Lord Goderich.

Kerr’s many difficulties induced him to support whole-heartedly a collective effort by the Lower Canadian bench, launched in 1824, to obtain independence for the judiciary from the legislative and executive branches of government. Under Sewell’s leadership the judges sought guaranteed salaries and pensions in order to free themselves from dependence on the assembly, and commissions during good behaviour in order to render them autonomous of the royal pleasure. On the other hand, like all the judges, Kerr opposed the assembly’s efforts to ensure the independence of the judiciary from the councils by removing judges from seats on those bodies. He feared that such action would limit the royal prerogative of appointment and deprive the councils of valuable members. He was also concerned, however, about the further loss of income that he would suffer. Thus, in 1831, when asked by the governor, Lord Aylmer [Whitworth-Aylmer], to resign from the Executive Council and to refrain from attending the Legislative Council, he complied but requested 6,000 acres of land for himself and 1,200 for each of his children as compensation. The request was refused.

Early in 1832 the assembly demanded Kerr’s suspension from his judgeships on the basis of several of Gugy’s charges. In particular, Kerr was accused of lacking knowledge of Lower Canadian law, “acting partially and unjustly,” displaying “a want of Temper and Courtesy,” not paying attention during hearings, rendering contradictory judgements, and illegally reversing his decisions. The assembly also argued that Kerr’s two judgeships were incompatible. Aylmer refused to suspend Kerr, and Goderich dismissed the charges since Kerr had been given no opportunity to defend himself. None the less Kerr left for England in 1833 to vindicate his character and to present various claims to the Colonial Office and the Admiralty.

Kerr had long been demanding compensation for revenue lost after the Admiralty’s prize court had been removed from Quebec to Halifax in 1801. The Admiralty insisted that he first pay £1,190 in droits which he had retained since 1816. In England that year, Kerr had deposited the money with his agent but had then been forced to draw on it to pay his passage back to Lower Canada. Obliged to settle with the Admiralty in 1834, Kerr was forced to borrow since the assembly in recent years had often refused to vote the civil list and the judges were owed substantial arrears in salary. To his dismay, not only was his claim to £4,088 for the loss of prize fees refused, but on 24 Sept. 1834 he was dismissed as judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court for having “Kept back a Sum of money belonging to the Public on Excuses not strictly correct.” Kerr had barely begun to prepare a protest when he learned that his resignation as judge of the Court of King’s Bench was required because of his dismissal from his other judgeship. Kerr’s protests to the Admiralty, the Colonial Office, and friends such as Dalhousie, largely on the grounds of long and loyal service and of expenses necessary to the maintenance of his social position, were to no avail. He stalled for time in hopes of being able to negotiate a pension or obtain more favourable treatment under a new government. He then refused to resign, arguing that to do so would constitute admission of guilt, and he was eventually dismissed. After his return to Lower Canada in 1836 he disputed with the Colonial Office the termination dates of his commissions and claimed £1,200 in arrears of salary. He published a petition to the House of Commons for redress but obtained nothing.

By January 1837 Kerr had suffered “an attack of paralysis of the head.” Unable to speak, he lived in retirement until his death, apparently with reduced means since he was supported by his children. A devout member of the Church of England, he sought comfort in daily readings of the Bible. To the end Kerr viewed himself as a sacrificial victim offered by the British government to appease a factious assembly, whose enmity he had aroused by his loyal defence of the royal prerogative. He was probably no less competent than many of his colleagues, but his indebtedness and continual grasping for fees and emoluments ultimately led to his downfall.

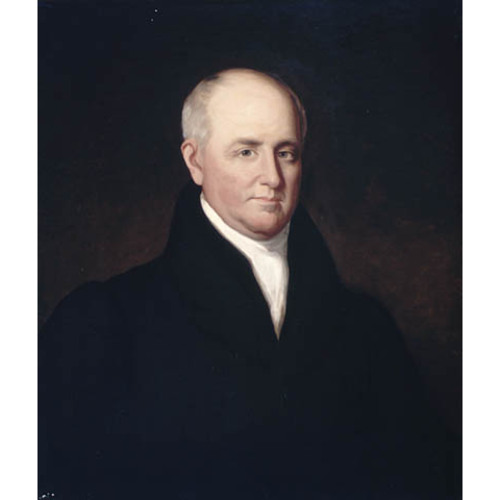

James Kerr is the author of Letter to Mr. Clark Bentom ([Quebec, 1804]) and Petition of James Kerr, esq., to the Honorable the House of Commons (Quebec, 1836). An oil portrait of Kerr is at PAC, Picture Division.

ANQ-Q, CE1-61, 12 juin 1816, 11 févr. 1821, 8 mai 1846; CN1-253, 23 août 1824; P1000-55-1054; Z300076 (microfiche), James Kerr et famille. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Geneal. Soc. (Salt Lake City, Utah), International geneal. index. Inner Temple Library (London), Admission records. PAC, MG 24, B167; RG 4, B8: 6325–27 (mfm. at ANQ-Q); RG 68, General index, 1651–1841. PRO, CO 42/223; 42/230; 42/236–38; 42/240–41; 42/244; 42/253; 42/255; 42/260; 42/277 (mfm. at ANQ-Q). Docs. relating to constitutional hist., 1819–28 (Doughty and Story), 238–39. L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 1835–36, app.V; Legislative Council, Journals, 1823–31. Ramsay, Dalhousie journals (Whitelaw). Quebec Gazette, 24 Aug., 5 Oct., 14 Dec. 1815; 1 Feb., 13 June 1816; 23 Oct. 1820; 26 Nov. 1821; 1 Jan. 1824; 11 May 1846. Quebec Mercury, 9 Feb. 1832. Browne’s general law list, being an alphabetical register of the names and residences of all the judges, serjeants, counsellors . . . attornies (12v., London, [1777–97]), 1793. Hare et Wallot, Les imprimés dans le Bas-Canada. The matriculation albums of the University of Glasgow from 1728 to 1858, comp. W. I. Addison (Glasgow, Scot., 1913). H. J. Morgan, Sketches of celebrated Canadians. P.-G. Roy, Les juges de la prov. de Québec. Buchanan, Bench and bar of L.C. Rumilly, Papineau et son temps.

Cite This Article

Paulette M. Chiasson, “KERR (Ker), JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kerr_james_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kerr_james_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Paulette M. Chiasson |

| Title of Article: | KERR (Ker), JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1988 |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | December 6, 2025 |