Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

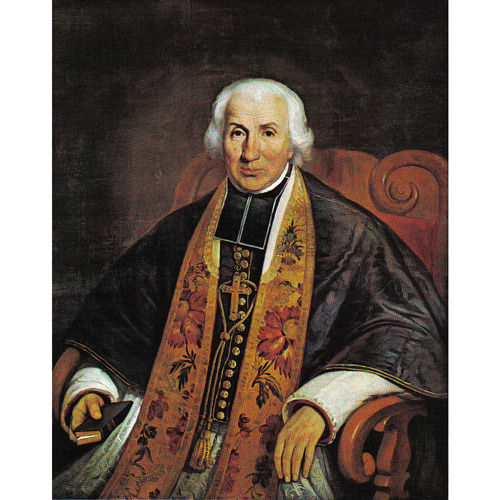

SIGNAY, JOSEPH (he signed Signaÿ, adding the accent still occasionally used at the time), Roman Catholic priest and archbishop; b. 8 Nov. 1778 at Quebec, son of François Signaï and Marguerite Vallée; d. there 3 Oct. 1850.

There were 11 children in the Signay family, but all except Joseph died before reaching adulthood, most of them in infancy. The ninth in the family, Joseph was raised by his mother, for his father, a seaman, was often away from home. He entered the Petit Séminaire de Québec in 1791 and proved a gifted and studious pupil. Six years later he went to the Grand Séminaire, where he studied until 1802. Although he taught at the Petit Séminaire while doing his theological studies, he none the less did extraordinarily well.

Signay was ordained priest by the bishop of Quebec, Pierre Denaut*, at Longueuil on 28 March 1802, and was named assistant priest at Chambly and then at Longueuil; he was made curé of Saint-Constant parish on 1 Oct. 1804. A year later he became the first parish priest of Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir (Saint-Nom-de-Marie in Marieville), with responsibility for visiting and ministering to Catholics around Missisquoi Bay. During his nine years there he gained a reputation as an able administrator.

In the autumn of 1814 the parish priest of Quebec, André Doucet*, resigned, and rumour had it that Signay would be appointed to replace him. Signay himself was strongly opposed but, at the insistence of Bishop Joseph-Octave Plessis* of Quebec, on 19 November he officially took charge of the parish. Its finances and religious edifices were then in poor condition. True to his reputation, Signay soon set them in order. He never went beyond the parish but did cover it from one end to the other; he even conducted censuses in 1815 and 1818. He also took a great interest in the education of young children; according to his contemporaries he had a special gift for teaching them the shorter catechism.

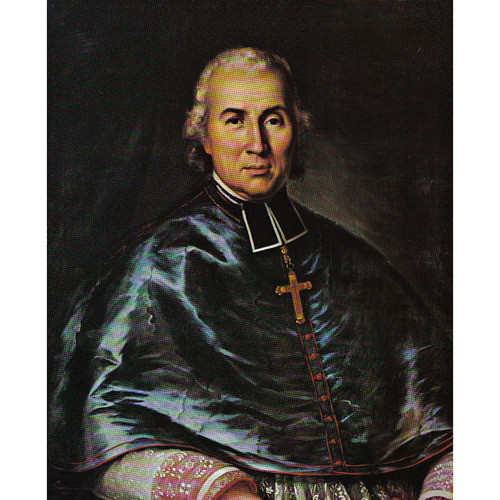

When Plessis died on 4 Dec. 1825, Bernard-Claude Panet* succeeded him as archbishop and announced that he had chosen Signay as his coadjutor. Although the appointment was approved by Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay], ratification was slow in coming from Rome, because Panet had sent only Signay’s name, rather than the three required; in addition, Bishop Jean-Jacques Lartigue, the archbishop of Quebec’s auxiliary in Montreal, expressed some reticence when consulted. Panet succeeded in overcoming these obstacles, and the bulls were finally signed by Rome. On 20 May 1827, in the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Quebec, Signay was consecrated bishop in partibus of Fussola. He remained parish priest of Notre-Dame, nevertheless, until 1 Oct. 1831. On 13 Oct. 1832 Panet resigned and handed administration of the diocese over to his coadjutor. The authorities in Rome accepted his resignation. Panet died on 14 Feb. 1833, and two days later Signay became the third archbishop of Quebec.

Signay also had great difficulty in getting recognition for his chosen coadjutor, Pierre-Flavien Turgeon*, because of opposition from the Sulpicians and pettifogging from Rome. Backed by the majority of his clergy, Signay insisted on ratification of his choice and won. On 27 Jan. 1834 the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda assented, but requested that the archbishop of Quebec be told “the hasty and irregular nomination of the coadjutor has immensely displeased the Sacred Congregation” and “the normal procedure is to be firmly respected in future.” Turgeon was consecrated bishop of Sidyma on 11 June 1834.

The victory was due largely to the work of the archbishop’s procurator in Rome, Abbé Thomas Maguire*, who also helped get two other problems examined: the property of the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice and the erection of the diocese of Montreal. The first problem had arisen many years before [see Jean-Henry-Auguste Roux*], but it became acute when in 1827–28 the Sulpicians indicated that they were ready to come to terms with the British government in the matter of their seigneurial rights. Alerted by newspaper accounts, both clergy and people voiced strong opposition, and Signay followed his predecessors’ example in denouncing the idea. Maguire was consequently given the task of correcting the statements made in Rome by Sulpician Jean-Baptiste Thavenet and of requesting that the Sulpicians be strictly forbidden to negotiate with the government. The cardinals of Propaganda went only so far as to request in 1834 that nothing new be done and that they be consulted before any further attempt at negotiation. In fact the problem was resolved when the Sulpicians came to a meeting of minds with Lartigue about the creation of the diocese of Montreal.

Lartigue’s appointment as auxiliary bishop in 1820 had greatly displeased his Sulpician colleagues, and he had become convinced that the difficulties would disappear if he were made bishop of Montreal and a diocese were erected. He had consequently put pressure on Plessis, Panet, and Signay to get a decision from Rome without waiting for London’s assent. Like his predecessors, and despite repeated requests from his auxiliary, Signay pleaded instead for prudence and compromise, and long maintained that the British authorities’ agreement was an essential preliminary. In February 1835, however, he resolved to write directly to Propaganda with the request for a diocese, but Rome was slow in replying. Relations between Lartigue and the Sulpicians improved, particularly on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Sulpician Jacques-Guillaume Roque’s ordination to the priesthood, on 24 Sept. 1835. The superior, Joseph-Vincent Quiblier*, even had the clergy sign a petition in favour of the erection of a diocese. When asked to transmit it to Rome Signay again delayed, to give himself time to sound out the civil authorities. On 24 December he finally gave in to Lartigue’s entreaties. The petition, with clarification and support from Bishop Joseph-Norbert Provencher*, who was in Rome at the time, was examined by Propaganda in March 1836, but the bull erecting the diocese did not reach Montreal until 29 August.

These events revealed that the bishops of Quebec and Montreal already had differing perceptions of some problems; in the ensuing years the differences became more marked on the subject of relations between church and state, as well as on the governance of the Canadian church. Whereas Lartigue and his coadjutor Ignace Bourget*, as faithful ultramontanists, advocated a policy affirming the church’s independence of the state, Signay, who was “purely and simply a man of the status quo” according to Father Jean-Baptiste Honorat*, preached respect for customs, prudence, and collaboration with the British authorities. He endeavoured to avoid all confrontation with the government and chose to shelve certain legitimate claims. The three bishops agreed, however, on one general principle: the clergy should be neutral in politics, except when religious interests were threatened.

The principle was particularly relevant at the time of the 1837–38 uprisings. Because the Quebec region remained relatively calm, Signay let events follow their course and did not intervene until after the first armed clashes had taken place. He asked the parish priests in the lower St Lawrence area to explain to their flocks that the troops arriving from the Maritimes were being called in not “for hostile purposes” but “to protect the inhabitants of the country and to maintain peace and order.” On 11 Dec. 1837 he published a pastoral letter denouncing the insurrection as “a means . . . not only ineffectual, unwise, and fatal to those who make use of it, but also criminal in the eyes of God and our holy religion,” and he warned his diocesans to watch for anything that might disturb the peace.

Signay’s customary prudence was intensified in the late 1830s by the climate of insecurity and depression in Lower Canada. He was in favour of the Canadian clergy’s address to the British parliament against the union of Upper and Lower Canada (it would eventually be forwarded in April 1840). But he also thought it useful in June 1838 to ask his priests to make known the views of the new governor, Lord Durham [Lambton], “either by having his proclamation read at the church door, or by any other means that prudence may suggest.” In January 1840, however, he again urged his clergy to use their influence to secure signatures for a petition against the union; he and his coadjutor Turgeon talked with Governor Charles Edward Poulett Thomson about the disastrous consequences of the imperial plan, and he congratulated Bourget on the firm language he had used with the governor.

From then on Signay left the initiative more and more to Bourget, the new bishop of Montreal, and sank into an “apathetic state” decried by a number of people. For example, when an education bill was introduced in 1841, he did not make known his reservations until after a violent denunciation of it had appeared in the Mélanges religieux, and some thought his remarks far too mild. He took the same attitude to the idea of setting up an ecclesiastical province, which had been entertained for a long time. Although Signay saw only the disadvantages and feared that it would be rejected by the imperial authorities, Bourget took up the matter with the Canadian bishops and presented the case to Rome. While awaiting a reply from Propaganda, he managed by his tenacity to calm the fears of Signay and his coadjutor and have them sign a petition to the Holy See in January 1843. In December Bourget sent Hyacinthe Hudon to Rome to further the cause, which was finally successful: in May 1844 the ecclesiastical province of Quebec was created.

A metropolitan against his will, Signay did everything he could to keep the promotion from taking effect. He was reluctant to receive the pallium and accepted it in November 1844 only on condition that “the immediate organization of the eccesiastical province not follow.” Similarly he did not approve the holding of a provincial council. He said that in principle he was in favour of a gathering of this sort but wanted to delay calling it until the “relations desirable among those bishops who must take an active part in this work have been established beforehand.” No such development occurred before his resignation, a step some people thought desirable in itself.

Bourget was one of those people. More and more irritated by Signay’s failure to act and his neverending objections to suggested changes and improvements – such as standardization of the liturgy and discipline, preparation of a new catechism, and establishment of a university – the bishop decided he would take advantage of a planned visit to Rome to call for his superior’s resignation. He informed Signay of his intention in a letter of 25 Sept. 1846, which summed up the reasons that he proposed to lay before the pope: the archbishop’s inertia as an administrator, the low level of respect and confidence he inspired, his inability to deal with important matters, and his lack of close relations with the suffragan bishops. Signay was deeply hurt by Bourget’s frankness and did not realize that the bishop of Montreal was expressing sentiments widely shared. As far back as 1835 Le Canadien had denounced the archbishop’s despotic rule. Vicar general Alexis Mailloux* was no less severe and wondered whether Signay had “the knowledge and the firmness combined with the independence from all human power that make a bishop what he must be.” At “the wish” of the secretary of Propaganda, visiting French historian Abbé Charles-Étienne Brasseur* de Bourbourg also wrote an indictment denouncing Signay’s extreme timidity, his stubborn and meddlesome disposition, and his inability “to take in the whole picture or enter into the details of orderly administration”; he furnished many examples of “the archbishop’s incompetence,” and of the savage opinions being circulated about him. This denunciation, kept secret at first, would appear almost word for word in Brasseur’s Histoire du Canada, de son Église et de ses missions, which was published in 1852.

Although in large part justified, these accusations took little account of other, more positive, aspects. Timid as he was, Signay did defend his priests against the government, and with success. His contemporaries praised his zeal and his spirit of charity; when disasters struck the town of Quebec – two cholera epidemics and the burning of the faubourgs Saint-Roch and Saint-Jean – he was the first to organize relief and urge people to help others. He did not hesitate to make his financial contribution in these instances, as well as at the time the bishop’s palace and the Séminaire de Nicolet were being built. He also took an interest in the missions and set up the Society for the Propagation of the Faith in 1836. His piety and his fondness for well-run ceremonies and for the liturgy in general were universally recognized.

Acquainted by Bourget with the situation in the archdiocese, the pope, not wanting to force Signay’s resignation, thought a simple indication to the archbishop that he would be pleased to receive it would be sufficient. When in February 1847 Bourget informed Signay of the pope’s attitude, the archbishop presented his own defence to the sovereign pontiff, saying at the same time that he was ready to resign. Rome did nothing. Dissatisfied, the bishop of Montreal threatened the archbishop with an accusation signed by the suffragan bishops. On 10 Nov. 1849 Signay handed administration of the archdiocese over to his coadjutor. Rome’s acceptance of his retirement finally arrived in March 1850, when Signay’s death was only a few months away. On 1 October he suffered a paralytic stroke, and two days later he died. In a detailed will he divided his property among various heirs, including the Séminaire de Nicolet, his servants, and the poor in the parish of Notre-Dame de Québec. His funeral occasioned the customary formalities, and Abbé Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau* delivered the eulogy.

AAQ, 12 A, N: 192; 31-13A; 20 A, VI: 35, 38, 44, 52; VII: 1, 70; 1 CB, X: 175; XIII: 71, 75, 79, 81; XVI: 79; CD, Diocèse de Québec, I: 138, 163–64, 167, 180–81, 183, 194; VI: 161, 193; VII: 134; 515 CD, III: 149; IV: 20–21, 60; VI: 112, 224; 516 CD, I: 22, 70–70A, 73A, 77; 61 CD, Notre-Dame-de-Québec, I: 18, 57, 60–61, 63; 10 CM, IV: 189A, 209, 214; 11 CM, II: 141; 310 CN, I: 150; 60 CN, II: 26–30, 58, 61; IV: 135, 137; V: 126; VII: 31; 26 CP, III: 148; IV: 147; V: 165; VI: 230; IX: 41–42, 71–71A, 72; C: 91–92; H: 132; 30 CP, I: 3, 6–7; Sér.E, II: 24, 38; IV: 56. ACAM, 295.098–295.101. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 9 nov. 1778, 7 oct. 1850. Archivio della Propaganda Fide (Rome), Acta, 1834, 194; Scritture riferite nei Congressi, America settentrionale, 5 (1842–48). ASN, Lettres des évêques, Signay à Harper, 1830–49; Signay à Raimbault, 1826–41. ASQ, Évêques, no.9, 30 nov. 1836; no.218, 2 mai 1841; Journal du séminaire, I, 10 sept. 1850; Lettres, W, 79; Y, 24, 26–27, 32;

Cite This Article

Sonia Chassé, “SIGNAY (Signaÿ), JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed May 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/signay_joseph_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/signay_joseph_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sonia Chassé |

| Title of Article: | SIGNAY (Signaÿ), JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | May 29, 2025 |