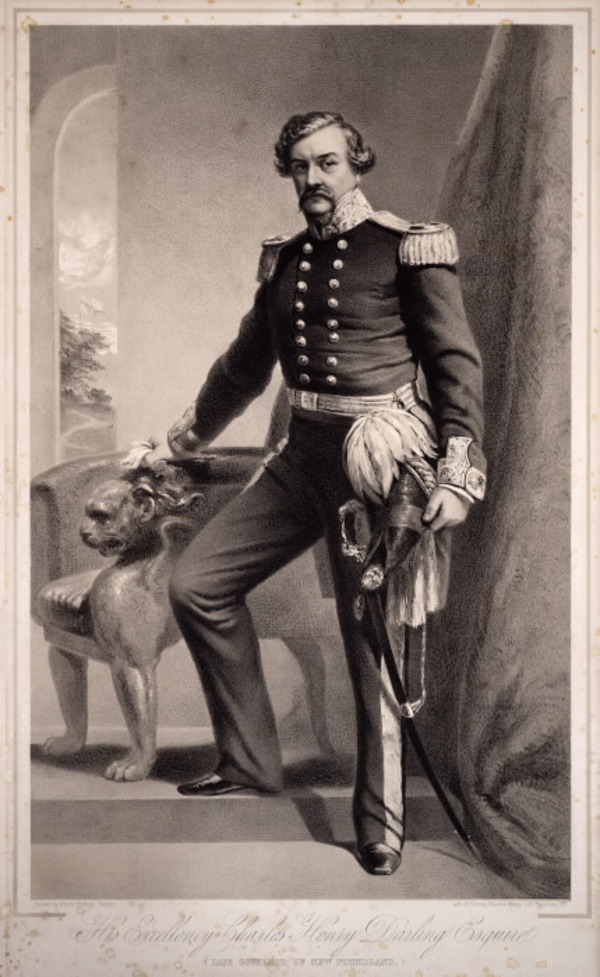

DARLING, Sir CHARLES HENRY, soldier and colonial administrator; b. 19 Feb. 1809 in Annapolis Royal, N.S., eldest son of Major-General Henry Charles Darling* and Isabella Cameron, daughter of a former governor of the Bahamas; d. 25 Jan. 1870 in Cheltenham, England.

When Charles Henry Darling was born, his father was a lieutenant-colonel attached to the militia in Nova Scotia. In December 1826, following an education at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, England, he began a military career as ensign in the 57th Foot. He was stationed with his regiment in New South Wales between 1826 and 1831, and for part of this time was assistant private secretary, then military secretary, to his uncle, Governor Sir Ralph Darling. He became a lieutenant in 1830, and in 1831 obtained leave to re-enter Sandhurst as a student in the senior department. He remained there until 1833, when he was appointed military secretary to Lieutenant-General Sir Lionel Smith, under whom he served in Barbados and the Windward Islands, 1833–36, and then in Jamaica until 1839.

Darling retired from the army in 1841 as a captain following two years in command of an unattached company. He had married twice, first, in 1835, the daughter of Alexander Dalzell of Barbados, who died in 1837, and in 1841 the eldest daughter of Joshua Billings Nurse, member of the Barbados Legislative Council; she died in 1848. Between 1843 and 1847 Darling served as agent general for immigration in Jamaica under the governorship of Lord Elgin [Bruce]; he became a member of the Legislative Council and adjutant-general of militia. After Elgin’s departure he was to serve again as a governor’s secretary.

Darling served as lieutenant governor of St Lucia from 1847 to 1851, and of Cape Colony (South Africa) during the absence of the governor in 1851. In that year he married Elizabeth Isabella Caroline Salter of Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire. From May to December 1854 Darling again administered the Cape Colony. At this time he was appointed governor-in-chief of Antigua and the Leeward Islands, but the colonial secretary, Sir George Grey, asked him to go to Newfoundland instead.

Darling was sent to Newfoundland to smooth the way for responsible government, which the incumbent governor, Ker Baillie Hamilton*, had made difficult by his anti-Liberal partisanship. In March 1855 Hamilton was told of his transfer to Antigua, and Grey remarked that Darling would “have the advantage of meeting the new assembly, and commencing the responsible system without any former connexion with the Politics of the Island.” Hailed as a man of experience in colonial affairs by the attorney general, Edward Mortimer Archibald*, Darling commenced his governorship by announcing the inauguration of responsible government. He came close to serious trouble, however, because he arrived without instructions to divide the old Council into its necessary executive and legislative parts, as was the established practice in colonies with responsible government. Happily for Darling the key members of that Council were anxious to go. Attorney General Archibald, Colonial Secretary James Crowdy, and Surveyor General Joseph Noad* arranged that their resignations would be accepted if the new assembly to be elected in May 1855 indicated a Liberal leadership. Subsequently the election returned a clear Liberal majority and on 22 May the new assembly passed resolutions designating Philip Francis Little*’s Liberal party the victors and the only possible source of the first Executive Council under responsible government. A stiff-necked governor could have insisted on his prerogative to decide that issue, but Darling let the slight pass with a mere rebuke to the assembly in the speech from the throne on correct constitutional practice.

The resolution in favour of Little’s party had the effect of dissolving the old régime, and Darling’s willingness to accept them surprised the Liberal members who had expected a fight. Fortunately, too, the Liberals were strong enough in the assembly to vote down resolutions proposed by Hugh William Hoyles*, leader of the Conservative and Protestant opposition, which charged Darling with unconstitutional conduct. Two productive sessions followed in 1855 and 1856. This era of relatively good feelings, though brief, was aided by the improved economic conditions resulting from the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 with the United States in which Newfoundland had been included. However, the hoary French shore problem soon disrupted the harmonious political scene.

Since 1783 the French had claimed exclusive rights of fishery on Newfoundland’s western coast from Cape St John to Cape Ray; Newfoundlanders steadily challenged this claim and asserted a concurrent right to the fishery. In 1856 Henry Labouchere, the British colonial secretary, reopened negotiations with France on the basis of modifications of the 1851 proposals made by Sir Anthony Perrier, the British negotiator. Governor Hamilton had condemned the Perrier proposals to the satisfaction of the colony, but Darling now endorsed many of Labouchere’s suggested modifications, which would divide the French shore into two exclusive sections, one French and one British, and acknowledge the French right to take bait on the south shore; he argued that since the Americans could take bait there under the Reciprocity Treaty, it would be impossible to prevent the French from doing so. Though Darling did not accept all the terms of Labouchere’s new proposals, it was believed that his dispatch of July 1856 to Labouchere strengthened the colonial secretary’s resolve to complete the convention of 14 Jan. 1857. When it was presented a month later, the Newfoundland assembly and Legislative Council vehemently condemned it. Darling then declared himself “absolutely helpless” to implement the convention in the face of such unanimous opposition. Eventually Labouchere withdrew the convention, and sent off a dispatch promising “that the consent of the community of Newfoundland is regarded . . . as the essential preliminary to any modification of their territorial or maritime rights.”

Seriously compromised by this triumph of the assembly’s views, though he had heeded its protest, Darling left the colony in February 1857, amid bitter criticism, to become governor of Jamaica. Perhaps his new appointment was not a means of extracting him from Newfoundland, because it came in February before the protest had fully developed, but his alleged role in the negotiations may have hindered his usefulness to the colony.

In 1863 Darling received his last appointment, as governor of Victoria (Australia), among the best appointments of the colonial service. This one, however, ended abruptly in 1866 after a disagreement between Darling and the colony’s Legislative Council. He returned to England to live in Cheltenham where he died in 1870. He had been knighted in 1865 for “his long and effective public services.”

PRO, CO 194/144–51. Royal Gazette (St John’s), 15 May 1855–28 April 1857. ADB. DNB. G.B., WO, Army list, 1827–41. Gunn, Political history of Nfld., 139–49. Thompson, French shore problem in Nfld., 25–47.

Cite This Article

Frederic F. Thompson, “DARLING, Sir CHARLES HENRY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed May 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/darling_charles_henry_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/darling_charles_henry_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Frederic F. Thompson |

| Title of Article: | DARLING, Sir CHARLES HENRY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | May 30, 2025 |