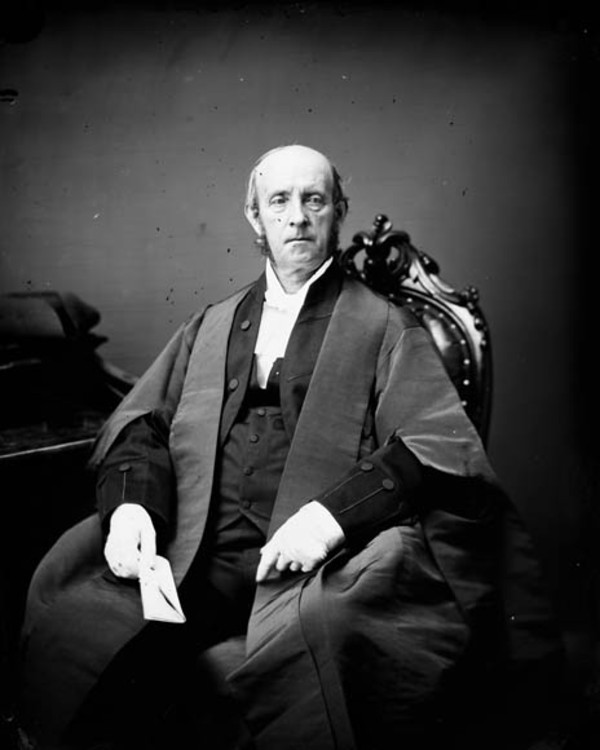

CHRISTIE, DAVID, politician and farmer; b. in Edinburgh, Scotland, in October 1818, son of Robert Christie; d. at Paris, Ont., 14 Dec. 1880.

David Christie was educated at Edinburgh High School; he was a good student, particularly well versed in Latin literature. In 1833 he came to Canada with his family. The next year his father took up a farm near St George in the southern part of Dumfries Township (in what is now South Dumfries Township), an area of largely Scottish settlement in the Grand River valley of Upper Canada. The Christie family was closely connected with the Dumfries Secessionist Presbyterian congregation, especially through David’s uncle, the Reverend Thomas Christie, a Presbyterian missionary in the district for the United Associate Secessionist Church, a fragment split from the established Kirk in Scotland. David was certainly exposed to the Dumfries church’s strongly held doctrine of voluntaryism – that churches should be voluntary organizations, not established, aided, or in any way interfered with by the state.

In the following years he also gained a strong interest in the improvement of agriculture, as he became an experienced farmer in his own right. By 1846 he was actively engaged in the movement to encourage better farming in Canada West through the holding of regular agricultural exhibitions. In August he was delegate to a meeting at Hamilton which set up the Provincial Agricultural Association. This in turn organized the first of an annual series of provincial fairs, held in Toronto that October. Christie again was a member of the committee that arranged the second provincial exhibition at Hamilton in 1847. He practised what he preached about agricultural improvement; in 1850 his own wheat won first prize at the fifth provincial fair in Niagara (-on-the-Lake).

Christie was emerging as a well-established, well-known member of the farming community, a fact signalled when, under the act of 1850 that incorporated the semi-official Board of Agriculture of Upper Canada, he was named one of its first members. He also served as reeve of Brantford Township in 1850, following the inception of the newly organized system of local municipal government for Canada West. And during the next decade he particularly gained a reputation as a stock breeder on the extensive new farming property he acquired between Brantford and Paris, though he was still engaged as well with the Dumfries farm. Further, he continued to be active with the Provincial Agricultural Association, becoming its second vice-president in 1851 and first vice-president in 1853, and being elected president in 1855 – at which time he gave an eloquent presidential address on the theme of agricultural education.

Christie had developed still another keen interest, provincial politics. He was a staunch Reformer in background and temperament; indeed, his political and religious views had much in common with those of his old Edinburgh schoolmate, George Brown, now editor of the Toronto Globe. The two Scots were in frequent contact by the late 1840s, and may well have been from Brown’s own arrival in Canada in 1843. Brown did not, however, share Christie’s enthusiasm for reforming the constitution along fully elective lines, once responsible government had been achieved in Canada by 1849; in supporting a British parliamentary pattern Brown stood with the main, moderate Reform group associated with Robert Baldwin*. But David Christie, full of zeal for democratic progress, turned toward a more radical element, concerned by the apparent tendency of the party to rest on its laurels, now that Reform had gained office as well as responsible rule.

The feeling that ministerial leaders were growing fat, if not unprincipled, in power was particularly likely to bring a response from Reform grassroots in agrarian Canada West. And Christie assuredly shared the rising demand among the farming community for cheap and simple government close to the people – not to mention the demand to abolish the clergy reserves system that gave churches (chiefly the Church of England) public funds from reserved lands. Accordingly, in the fall of 1849, he became engaged with a small but vigorous coterie who sought to remake the Reform party in a more radical image. This group, which included experienced politicians such as Malcolm Cameron and later Caleb Hopkins, as well as younger idealists such as Christie and William McDougall*, were quickly denominated the “Clear Grits.” There are several possible origins for the name, but “the best authenticated version,” according to John Charles Dent*, traces it to a discussion between Brown and Christie in the autumn of 1849 over the emerging radical movement, wherein Christie rejected any who might hang back like Brown, declaring, “We want only men who are clear grit.”

Although it is impossible now to document that origin, the Globe certainly began applying the term to the radicals in December 1849. Moreover, it was evidently accepted by them, connoting as it did thoroughgoing reform integrity: in early 1850 they formulated a “clear grit” platform calling for elective institutions throughout, universal suffrage, and secularization of the reserves. By the following summer they had made sufficient impact in parliament to cause Baldwin to resign as premier. The Francis Hincks*–Augustin-Norbert Morin* Liberal regime that succeeded had to admit two Clear Grits, Cameron and John Rolph*, to the cabinet, a bargain worked out in July 1851 by McDougall and Christie. And in the ensuing general elections at the close of the year, Christie successfully ran for Wentworth County, which then included the Brantford area, to enter parliament at the age of 33.

Brown had meanwhile broken with the Reform ministry, because it had failed to settle the reserves question and had fostered Roman Catholic separate schools, but he continued to oppose the Clear Grits because of their advocacy of elective institutions and because they themselves, as he saw it, had now sold out for office. Undoubtedly Christie found himself in a difficult position after parliament opened in August 1852. The Hincks government showed more interest in promoting the new railway era than in taking up basic constitutional reform. Besides, not only did it still hang back on the reserves, but it also supported further enlargements of Catholic separate school rights in Canada West and incorporations of Catholic religious bodies in Canada East, thanks largely to the powerful French Canadian influence in its midst. These proceedings were sorely compromising for Grit ministerial supporters such as Christie, scarcely less voluntaryist on church-state issues than Brown. Indeed in January 1853, during the parliamentary recess, Christie met Brown in a grand public debate back in his constituency at Glen Morris, and, despite bold efforts to justify his support of the ministry, came off second best.

Nevertheless, Christie continued to hold a prominent place within Grit circles, a fact displayed when McDougall, voicing his own discontent with the Hincks government in a letter to Charles Clarke* in September 1853, even suggested that Christie might replace Hincks as leader. By 1854 the mounting strains between the eastern and western sections of the existing Canadian union and the unrest within Reform itself in Canada West, threatened to upset the government. In June it was beaten in the house, and elections were quickly called. This time, Christie stood for East Brant, one of two constituencies in the new county of Brant which had recently been divided off from Wentworth. He was narrowly defeated by a Conservative candidate, Daniel McKerlie – because, he said, “I had the whole Brown influence against me.” Still worse, when parliament met in September, the Hincks and Morin Liberals joined with Conservative forces to establish the Sir Allan MacNab*–Morin Liberal-Conservative government (“Awful treachery” to Christie). At least the new coalition was committed to secularize the reserves. Christie himself had hopes of overturning McKerlie’s one-vote lead through contesting the electoral verdict. He still affirmed, “I have full confidence in Democratic principles. . . . The people will be brought to see their duty.”

The electoral commission decided in Christie’s favour in March 1855, and he was again seated in the Legislative Assembly. Here he found the Reform factions left in opposition beginning to form a common front against their Liberal-Conservative foes. In particular, the Clear Grits and Brown were moving together, as the former set aside their demand for elective institutions, at least for the present, and the latter concentrated on representation by population, to overcome eastern Conservative and French Catholic power in the Canadian union.

Like many Clear Grits, Christie was inclined to favour the outright repeal of the union of the Canadas, considering representation by population “a just and righteous thing” but “too slow a remedy.” He nevertheless gradually came around in response to Brown’s and the Globe’s forceful appeals for Reform unity. By September 1856 he could write: “Our friend Brown is wrong on many points. I suspect he will never go the length of constitutional changes and repeal. . . . He is a powerful man [however]. . . . We did right in standing by him.” This knitting up of party ties, qualified as it might be, was symbolized by the Reform Convention of January 1857 in Toronto, which Christie attended. Indeed, he was one of the signers of the requisition calling it.

The reunited Reform forces carried Canada West in elections held late in 1857. Christie, returned again for East Brant, was on hand for the major debates on the ills of the union in the session of 1858 and the hectic summer change from the John A. Macdonald*–George-Étienne Cartier Conservative government to Brownite Liberals, and swiftly back to Macdonald and Cartier again. In the autumn, however, he campaigned for a seat in the upper house, the Legislative Council. This had been made elective in 1856, and it was a less demanding arena than the assembly. Hence he would have more time for his growing farm outside Brantford; and he was also involved in local railway development: earlier in promoting the Buffalo and Brantford line (which became the Buffalo and Lake Huron Railway), and now in negotiating with Buffalo interests for a bridge to give direct rail access over the Niagara River. He was elected for the Erie division (which included his home territory) of the Legislative Council, and in December resigned his seat in the assembly.

He continued to be prominent in the Reform party. At the grand Reform Convention of November 1859, in Toronto, he was one of the vice-chairmen and a member of the key committee that controlled the structure of the sessions – although Brown’s close associates still kept an effective grip upon them. At the convention, indeed, Christie seemed to have dropped some of his earlier outright radicalism. He did not support a demand for repeal of the union, and instead endorsed the Brownite call for a federation of the two Canadas as a step towards a future general British North American federation. Yet the next year he was informing one enduring radical associate, William Lyon Mackenzie*, that the convention’s federal scheme would not do: “I now see that the only thing to save Upper Canada is a Simple Dissolution of the Union.” In any case, Christie’s role was now more one of prestige than of party influence. His political activities had less significance in the upper house, and old Grit radicalism had largely been tamed within the Brownite Liberal party. Accordingly, he played no very weighty part in politics in the early 1860s, as the Canadian union wound through mounting crises to complete deadlock in 1864. But when out of deadlock came the coalition of Brown, Cartier, and Macdonald to seek confederation, Christie gave it earnest support from his place in the Legislative Council. At the same time he advised the government on patronage questions in the Brant area as a leading Reform figure there.

During the confederation debates of 1865, when the plan for federal union was put to parliament, Christie spoke strongly in the council in favour of the scheme. True to his past, he did criticize the proposed federal Senate because it was to be an appointed, not an elected body: “I have always been an advocate of the elective principle.” Still, he said, “I shrink from the responsibility of voting against the scheme because of that objection.” And the next year, when it was enacted that existing members of the Legislative Council of Canada should be appointed to the Senate of the new confederation, Christie, at the end of his eight-year elected term, proceeded to accept a life position in the future federal upper house.

With the coming of confederation he remained actively involved in Liberal affairs. He attended the Reform Convention of June 1867 in Toronto; he worked faithfully in the party interest in the elections that followed, both in the federal sphere and in that of the new province of Ontario; and he sought to maintain his strong political influence in Brant County. Yet, as Sir John A. Macdonald shrewdly pointed out to a disconsolate local Conservative in October 1867, having become a senator had really greatly reduced Christie’s importance: “the fact of being a nominee of the Crown instead of the choice of the people deprives him of any real hold.”

In the following years David Christie nevertheless remained to the fore in the Senate itself; he had become one of the patricians of Liberalism. Thus, when Alexander Mackenzie* formed a Liberal government in November 1873, he was named secretary of state in the cabinet. But after the government won a sweeping election victory he was moved to the post of speaker of the Senate in January 1874, a post more honorific and less onerous, which he held with distinction until his resignation in October 1878 when the Mackenzie government fell. Although not an eloquent orator, Christie had forceful dignity, straightforward logical clarity, and a judicious choice of words that earned him respectful attention. After he left the speakership at the age of 60, he virtually withdrew from public life. Still, even in the years before, much of his most significant activity had not been in the Senate at all.

He had especially kept his interest in agricultural development; for example, he had served in various capacities in the Provincial Agricultural Association, and was its president again for the last time in 1870–71. In 1873 the Liberal government of Oliver Mowat* in Ontario named him a member of the commission which was responsible for setting up the Ontario School of Agriculture (later part of the University of Guelph). Subsequently, in 1880, he was president of the Dominion Council of Agriculture and of the American Shorthorn Breeders Association, an international body. He also sat on the Senate of the University of Toronto from 1863, and briefly in 1875 was administrator of the province of Ontario, during the illness of Lieutenant Governor John Willoughby Crawford.

Meanwhile, he had continued to make his own estate, “The Plains,” an agricultural showplace. The Dumfries property was also held until 1871, and by 1868 Christie already had, by deed, some 540 acres in his Brantford Township estate, on which he built a handsome mansion. He had married Isabella Turnbull of Dumfries in 1848. She died in 1858, and in 1860 he was married again, to Margaret Telfer of Springfield in Elgin County. The Christies had a large family at their Plains residence, where they frequently housed friends, political allies, and visiting agriculturalists. Moreover, from 1866 onward, a one-time schoolfellow become political enemy and now again an increasingly close friend, George Brown, had been developing his own extensive farming estate at Bow Park on the other side of Brantford. In the 1870s the two became frequent visitors, happily reminiscing about past political battles. Christie, in fact, became vice-president of the cattle company which Brown incorporated for his large-scale pedigreed stockbreeding enterprise at Bow Park.

Like Brown’s, however, Christie’s final years were clouded by financial troubles. The deep depression of the later 1870s, the venture into the costly business of raising pedigreed cattle for a Canadian market not yet ready for it, undoubtedly had as much to do with his difficulties as with Brown’s. But Christie had no powerful Globe to fall back on, and he was much more seriously overextended. He went bankrupt. His household goods were sold at auction in Brantford in December 1879; he had to leave the Plains for quarters in nearby Paris. And there the next year he suffered a trivial wound in his foot which refused to heal. His exhausted state forbade the operation needed for gangrene. He died on 14 Dec. 1880, aged 62 – only months after George Brown: their two interconnected lives thus having coincided in the year of both birth and death.

Blue Lake and Auburn Women’s Institute (Paris, Ont.), “Tweedsmuir history” (copy in PAO). PAC, MG 24, D16 (Buchanan papers); MG 26, A (Macdonald papers), 339. PAO, Charles Clarke papers; Mackenzie-Lindsey collection. Brantford Weekly Expositor, 17 Dec. 1880. Canada, Province of, Confederation debates. Globe (Toronto), 10 Dec. 1849, 10 Jan. 1850, 22 Aug. 1851, 9 Jan. 1857, 11 Nov. 1859, 16 Dec. 1880. Weekly Globe (Toronto), 19 May 1876. Dom. ann. reg. 1880–81. Encyclopedia of Canada, III. Careless, Brown. Cornell, Alignment of political groups. Dent, Last forty years. C. M. Johnston, Brant County: a history, 1784–1945 (Toronto, 1967). W. J. Rattray, The Scot in British North America (4v., Toronto, 1880–84), II. James Young, Public men and public life in Canada . . . (2v., Toronto, 1912), I; Reminiscences of the early history of Galt and the settlement of Dumfries, in the Province of Ontario (Toronto, 1880).

Cite This Article

J. M. S. Careless, “CHRISTIE, DAVID,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/christie_david_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/christie_david_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. M. S. Careless |

| Title of Article: | CHRISTIE, DAVID |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 6, 2025 |