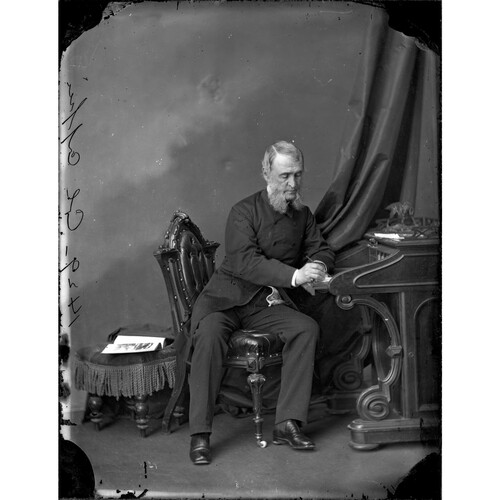

COFFIN, WILLIAM FOSTER, soldier, author, and civil servant; b. at Bath, Eng., on 5 Nov. 1808, son of an army officer and grandson of John Coffin*, a loyalist from Boston who moved to Quebec in 1775 and played a distinguished part in its defence against the Americans in 1775–76; d. at Ottawa, Ont., 28 Jan. 1878.

In 1813, William Foster Coffin’s family came to Quebec. His father being in the army, Coffin was aware as a child of the echoes of the War of 1812. He learned French at this time, at the home of the parish priest of Beauport. In 1815, with the war at an end, the Coffins returned to England and William spent the next nine years at Eton. Perhaps because his uncle Thomas* was living at Quebec and had become a member of the Legislative Council of Lower Canada, William looked to the colony for a career. In 1830 he came to Canada, articled in Montreal, and, after reading law with Charles Richard Ogden* and Alexander Buchanan*, was called to the bar of Lower Canada in 1835. Two years later, he was active among the volunteers organized against the Patriotes, serving as an interpreter and intervening to protect the habitants and church property from pillaging by these volunteers.

This background of law and loyalty helped to shape Coffin’s career in the ensuing years. In 1838 he was chosen by Sir John Colborne* to be assistant civil secretary for Lower Canada – an office created with a view to organizing a police force for the province – and in 1839 he became a police magistrate. In 1840, Coffin became commissioner of police for Lower Canada; two years later he was named joint sheriff of the District of Montreal, a post he resigned in 1851 when the legislature suddenly cut in half the income of the office. Coffin was frequently called on as a commissioner to investigate matters of law and order. In 1840 he looked into the state and condition of the Montreal jail; in 1841 he inquired into troubles on the Indian reserve at Caughnawaga and into election riots at Toronto [see George Monro]. In 1854 he investigated accidents on the Great Western Railway and, in the following year, he studied the affairs of the University of Toronto. In 1855 also, he was sent to maintain order on the Gatineau “then seriously threatened by refractory characters to the great disquietude of the lumbering interest.” Meanwhile, Coffin was acquiring land, wealth, and important interests in railways linking Montreal and New York.

In 1855, as a result of the Crimean War, Britain reduced her garrison in Canada to its lowest level in decades. Patriotic enthusiasm and anxiety at the possibility of war with the United States combined to persuade the government of the united province to revise the Canadian militia system. For the first time, formal authority was granted for the creation of units of volunteer militia. Coffin, a major in the older militia organization, was one of many who took advantage of the new legislation, forming the only militia field battery in Montreal. Since organizing field artillery involved hiring horses, recruiting men, and storing equipment, as well as mastering relatively complex training, only a man of enthusiasm and wealth could have managed so difficult a task.

To encourage Canadians to make permanent provision for their own defence, the British government decided to hand over, in 1856, most of its ordnance lands in Canada to the provincial authorities. With some misgivings, the Canadian government accepted the gift. At the suggestion of the governor general, Sir Edmund Walker Head*, Coffin was appointed commissioner for ordnance lands, a position he was to hold for the rest of his life. Choosing to establish himself in Ottawa, Coffin resigned his command of the Montreal battery, and received promotion to lieutenant-colonel as a final reward for his services.

Predictably, Coffin struggled hard to make Canadian government policy fulfil British expectations. The ordnance lands, he claimed, “represent a capital, the annual interest of which, if estimated as proposed, will exceed the present requirements of the militia of the Province.” Rent from land and buildings in Ottawa alone would yield a million dollars a year for defence purposes. Coffin’s efforts to secure the ordnance funds for Canadian defence were unavailing and his office and its revenues were soon swallowed up in the massive Crown Lands Department. For 18 more years he continued as a civil servant of first the provincial and later the dominion government.

Throughout his life, Coffin elaborated his claim that his grandfather had played the key role in saving Quebec in 1775 and, consequently, British power in North America. In the 1860s, with new threats of war with the United States, Coffin turned to a wider patriotic task in publishing 1812, the war and its moral. Although his younger contemporary, John Charles Dent*, condemned the book’s unflagging patriotic bias, he merely underlined Coffin’s own purpose: to combat the sensational American versions of the war and to offer “an antidote to the American literature of the day.” The heroism of Sir Isaac Brock*, Tecumseh*, Laura Secord [Ingersoll*], and the Canadian militia is presented with enough fervour to contribute significantly to a mythology known to a century of English Canadian schoolchildren. By accentuating the significance of Charles-Michel d’Irumberry* de Salaberry and the battle of Châteauguay, Coffin did his best to provide both the founding races of Canada with the heroic legends he felt were necessary for their common nationalism.

After his first book, Coffin continued to write, chiefly lectures. Those which survive in print, such as Thoughts on defence, from a Canadian point of view and Quirks of diplomacy, exhibit an increasing sense of Canadian nationalism. Even after the withdrawal of British troops from central Canada in 1870–71, Coffin argued that Canadians could defend themselves from the United States. If the British chose to be generous at Canada’s expense in their diplomacy with the United States, Canadians should be recompensed.

In 1873, Coffin declined the appointment of lieutenant governor of Manitoba. Five years later he died at his home, “Aux Écluses,” near Ottawa. In Boston, on 6 July 1841, he had married Margaret Clark, herself of loyalist and military stock. She and one son, Thomas, survived him.

PAC, MG 30, D62 (Audet papers), 8, 565–69. W. F. Coffin, 1812, the war and its moral; a Canadian chronicle (Montreal, 1864); Memorial of William F. Coffin to His Excellency Sir Edmund Walker Head (Montreal, 1855); Quirks of diplomacy; read before the Literary and Scientific Society of Ottawa, January 22, 1874 (Montreal, 1874); Thoughts on defence, from a Canadian point of view . . . (Montreal, 1870). Dom. ann. reg., 1878, 333–34. E. J. Chambers, The origin and services of the 3rd (Montreal) field battery of artillery, with some notes on the artillery of by-gone days, and a brief history of the development of field artillery (Montreal, 1898). Dent, Last forty years, II, 566. Hodgetts, Pioneer public service.

Cite This Article

Desmond Morton, “COFFIN, WILLIAM FOSTER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/coffin_william_foster_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/coffin_william_foster_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | Desmond Morton |

| Title of Article: | COFFIN, WILLIAM FOSTER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 6, 2025 |