Source: Link

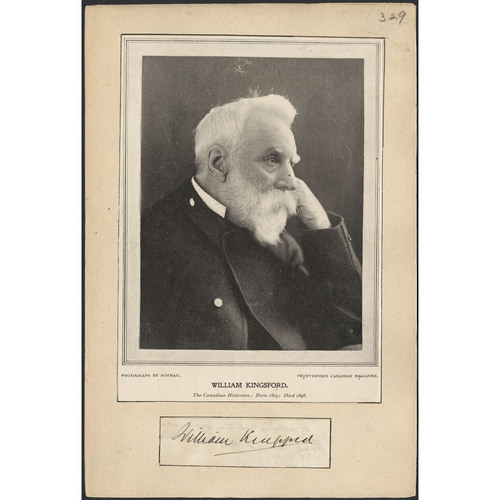

KINGSFORD, WILLIAM, soldier, surveyor, journalist, publisher, civil engineer, businessman, office holder, and author; b. 23 Dec. 1819 in the parish of St Lawrence Jewry, London, England, son of William Kingsford and Elizabeth ; m. 29 March 1848 Maria Margaret Lindsay in Montreal, and they had two children; d. 29 Sept. 1898 in Ottawa.

William Kingsford was the son of an innkeeper with means sufficient to send him to the school of the celebrated Nicholas Wanostrocht in London. Wanostrocht put his passion for cricket before more scholarly pursuits, and Kingsford thrived under this discipline; later a sturdy six-footer, Kingsford would demonstrate a life-long preference for physical activity over study, for the knowledge of experience over that of books. Upon leaving school he was articled briefly to an architect, but, “finding the office uncongenial,” he enlisted in the 1st Dragoon Guards in March 1838, on the eve of their departure to reinforce military units in Lower Canada in the wake of the rebellion of 1837.

Kingsford’s regiment was in Chambly in October 1838 and thus found itself the following month in the midst of the second uprising [see Robert Nelson*]. Under Lieutenant-Colonel George Cathcart it played a prominent role in both the suppression of the rebellion and the subsequent pillaging of rebel homes and farms. Kingsford had no sympathy for the Patriote cause but, “unaffected by the passions” of resident loyalists, he disapproved of reprisals against persons and property. With the countryside pacified, life in the cavalry lost its attraction for him, and in October 1841 he purchased his release at the rank of corporal.

Kingsford had learned the rudimentary techniques of land surveying while working under Cathcart’s supervision on the Chambly plank road. On the strength of this experience he obtained the position of deputy city surveyor of Montreal early in 1842; he was certified as a land surveyor in Lower Canada on 5 Nov. 1844, and in Upper Canada later, on 8 Oct. 1855. In 1844 he also began a shadow career as a journalist, joining Murdo McIver to found the Montreal Times. Never a reflective writer, Kingsford wielded the pen like a bludgeon on behalf of the Constitutional party and Governor Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*. He wielded a bludgeon of a more literal kind on the streets of Montreal during election riots in October 1844; captain in Saint-Laurent riding of his party’s vigilantes, variously styled the “black hussars” or “‘cavaliers,” Kingsford won the battle for control of the local polling station. His reform enemies took revenge two years later, assaulting and almost killing him; two wounds to the head marked his appearance thereafter.

Never content for long in any position, Kingsford resigned as deputy city surveyor in July 1845. When the Montreal Times folded the following year, he accepted a succession of temporary assignments as a surveyor across Lower Canada, determining the limits of crown property along the Lachine Canal, fixing the astronomical position of the lights at Cap-de-la-Madeleine, and supervising construction and maintenance of a portion of the Champlain and St Lawrence Railroad. In the process he assumed the duties and responsibilities of a civil engineer. These were the halcyon years when engineers were at the forefront of progress, building roads and railroads, canals and harbours, towns and cities. They were not yet professionals; adaptability was their hallmark, the market and their conscience were their only regulators. Kingsford was naturally attracted to the versatility and mobility of this way of life and was eminently suited for it by virtue of his energy and ambition.

In 1849 Kingsford moved to the United States. He surveyed, provided estimates for, and supervised the laying out of streets and the distribution of building lots in Brooklyn, N.Y., and then conducted a survey of the plank-road system for the state. From April 1850 to October 1851 he was assistant engineer on the Hudson River Railroad. He then moved to Central America, where for the first six months of 1852 he worked as the first assistant engineer on the northern division of the Panama Railway and then examined the water supply for Panama City. By October he was back in the Canadas; as engineer for the eastern division of the proposed Montreal and Kingston Railway, he surveyed and provided estimates for a line from Montreal to Cornwall, Upper Canada, and often filled in for the ailing chief engineer, Thomas Coltrin Keefer*. When the railway was swallowed up by the Grand Trunk Railway towards the end of the year, Kingsford retained his position and made numerous surveys and estimates for a line between Montreal and Bytown (Ottawa). He was also one of many engineers involved in the construction of the symbol of his profession and of the age of progress in the Province of Canada, the Victoria Bridge across the St Lawrence River at Montreal, on which work began in 1854 [see James Hodges*].

In June 1855 Kingsford accepted the position of city engineer in Toronto, but he resigned within months when he discovered that the salaries of his assistants were to be paid from his own. He returned to the Grand Trunk as superintendent and engineer in charge of construction between Belleville and Stratford. Early in 1856 he made the transition from employed engineer to hired contractor, and for the next four years he was in charge of running and maintaining the line from Toronto to Stratford. Understanding that one must “treat workers fairly and give good wages or risk disruption and disaster,” he was a successful employer, and he proudly claimed in 1861 that, under his hand, “not a single accident happened by defect of tracks or neglect of organization.” Apparently this record, and his ability to speak French, Italian, German, and Spanish, impressed the British contracting firm of Peto, Brassey, Jackson, and Betts, which was in charge of the Grand Trunk; that year Thomas Brassey hired him to examine “important works” in Europe east of Vienna and north of Naples.

Back in Canada in 1862, Kingsford acted as a consultant for a number of companies and individuals interested in speculative construction. In 1863, for instance, he examined the state of roads in and around Toronto for the York Roads Company, and in 1865 a group of businessmen hired him to study the possibility of building a railroad to Fort William (Thunder Bay, Ont.). That year he authored a book which recommended the deepening of locks on the St Lawrence River–Great Lakes system. In 1866 he returned to Europe for Brassey to examine the potential for a textile plant and railroad on Sardinia. He came back to Canada in the wake of confederation to report to “English capitalists” on contracting for the Intercolonial Railway. When it was decided to make this line a government project, Kingsford resumed the occupation of independent contractor and consultant.

Throughout these peregrinations across three continents and almost a dozen nations Kingsford kept a hand in journalism. From 1855 to 1858 he frequently contributed political commentary to the Daily Colonist in Toronto, attacking George Brown* for fanning the flames of anti-Catholicism and for recommending representation by population. In the early 1860s he also wrote theatre and music reviews, most often for the Montreal Herald. Kingsford’s travels themselves became the subject-matter of several articles as well as a small pamphlet and broadened his market. On his return from Europe in 1862, for example, he became Canadian correspondent for a London newspaper, defending the various ministries shaped by John A. Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier*; and when he went back to Europe in 1866 he acted as correspondent for the Leader (Toronto), reporting favourably on the London conference in December. A vocal Conservative and confederate, he looked forward to the development of a transcontinental nation on the spine of a transportation system constructed by engineers.

In 1870 Kingsford’s political sympathies and professional career converged. The major projects of the day were in the hands of the federal Department of Public Works, and it was in the hands of the Liberal-Conservative ministry. From 1870 to 1872 almost all of Kingsford’s work was done for the department; it included contracting on the Lachine Canal as well as on the Grenville and Welland canals in Ontario, and surveying the Ottawa and Gananoque rivers in Ontario and the Rivière Hudson in Quebec. In June 1873 his sympathies won him the post of engineer in charge of federal harbour and river works in Ontario and Quebec. His professionalism ensured that he kept the appointment when the Liberal party of Alexander Mackenzie took power in November.

Kingsford’s office surveyed harbours and rivers over which the federal government had responsibility; it determined, often in conjunction with leading local citizens and councils, what improvements should be made, estimated their cost, let contracts, and supervised the work. Most projects were small but politically charged, the building of a pier or the dredging of a channel being both an important source of employment and a sign of influence. To carry out this delicate task Kingsford had a staff of ten by 1879; it consisted of one assistant engineer and nine junior assistants or clerks of works. From May to December each year the assistant and three or four juniors surveyed, while the remainder of the staff supervised the progress of the operations; Kingsford was in constant motion to superintend, guide, and consult. From January to April he and his staff were in Ottawa to prepare the department’s annual report and plan the next round of improvements. He excelled and revelled in the life.

In performing his duties “faithfully and without sullenness” under Mackenzie, who acted as his own minister of public works, Kingsford aroused the suspicions of the Conservatives, who returned to power in October 1878. On 31 Dec. 1879 he was dismissed by the same minister who had hired him, Hector-Louis Langevin*, ostensibly because a departmental reorganization had rendered his post redundant. Considering himself a professional above politics, he fought long and hard to gain reinstatement. The issue occasioned one of the first major debates in the House of Commons on the incompatibility of traditional patronage and the new professionalism. Langevin, however, thought Kingsford disingenuous and went no further than to allow him a half year’s salary; his connection with the department ended altogether on 29 Feb. 1880.

Blocked from participation in public nation-building projects, too proud and, at 60, perhaps too old to find the lesser projects of private contracting rewarding, Kingsford returned to writing. Now, however, he shifted his focus from political commentary and technical manuals to Canadian history. His motives are not entirely clear: he had been collecting Canadiana for at least 20 years and, residing in Ottawa, he was attracted by the filling shelves in the archives branch of the Department of Agriculture under Douglas Brymner*; as well, he drew a parallel between the engineer building the sinews of the nation and the historian constructing its spirit. In any event, he dedicated the remainder of his life to writing a history of the British North American colonies through to the achievement of responsible government – which he dated from 1841 – based on original sources. He approached the task as would an engineer: he surveyed the existing material, excavated the relevant information, and hammered it into shape. He did so following a severe daily regimen which enabled him to complete the ten volumes of the History of Canada over 12 years, from 1887 to 1898. Each volume cost $1, 200 to produce, to raise which he mortgaged his house and furniture. Virtually broke by 1896, he was saved from ruin, and the project completed, only by the intervention of such friends as Sandford Fleming*.

Kingsford wrote as he built, quickly, without qualification or meditation, under pressure of time and budget. Thus, although he was among the first historians to use the archives branch extensively, his researches there were of necessity random and superficial, conducted to flesh out rather than alter received opinion. His themes of military, political, and constitutional history, although the preoccupations of his contemporaries, were inherited from his predecessors; his interpretations relied heavily on such precursors as Michel Bibaud*, Robert Christie*, and, especially, Lord Durham [Lambton*]. He assumed that the British conquest of New France was a victory for constitutional liberty and material progress, that the assimilation of French Canadians was inevitable, that the achievement of responsible government was the unifying heritage of all British North American colonies, and that ultimately Canada was one nation composed of a single people inhabiting a common land. Although his conventional views were often expressed with the zeal of a revisionist, his most arresting departures from historiographical norms were products less of new scholarship than of personal eccentricity. The result was a generally uncoordinated recapitulation of commonplaces, interrupted by irrelevant digressions and delivered in a pedestrian prose of interminable length.

The public applauded Kingsford’s diligence and self-sacrifice; he was honoured with an lld by Queen’s College (Kingston, Ont.) in 1889 and by Dalhousie University (Halifax, N.S.) in 1896 and was elected a member of the Royal Society of Canada in 1890. To his chagrin, however, it was increasingly clear that few individuals in fact read the tedious volumes they had felt duty-bound to purchase. Among those who made the effort were the country’s first generation of professional historians. In the pages of their new forum, the Review of Historical Publications Relating to Canada, they repeatedly took him to task for failing to meet their standards of comprehensive research and coherent argument. Some remarked briefly on his neglect of social and economic history. Always a good hater, but for unknown reasons denied the opportunity to respond by the Review’s editor, George MacKinnon Wrong*, Kingsford struck back in the Queen’s Quarterly. Although he often held his own in matters of detail, his reputation was thenceforth increasingly that of an amateur. Fortunately he did not live to endure the decline, and he would have appreciated the gesture of tobacco magnate Sir William Christopher Macdonald*, who in 1898 endowed the Dr William Kingsford Chair in history at McGill University. The endowment included provision for an annuity of $500 to be paid to Kingsford’s widow, to which was added a civil list pension of £100 per annum from Queen Victoria.

The dual career of William Kingsford provides insight into the process of professionalization in late-19th-century Canada. Often exhibiting the combative insecurity of the self-taught, Kingsford nevertheless had the ambition, will, and physical stamina necessary to push to the forefront of the still emerging profession of civil engineering. He did not, perhaps partly because of his irascible nature, achieve the prominence of Samuel Keefer* or Sir Sandford Fleming, and he was not a key figure in technological or organizational development. However, he was among the first practitioners of civil engineering, wrote books on the subject, held senior positions with major private firms and with the federal government, did battle on behalf of the professional status of his occupation, and, in 1887, was among the founding members of the Canadian Society of Civil Engineers. This career was only undone by the traditional practice of patronage. On the other hand Kingsford turned to the writing of history at a time when university academics were beginning to lay claim to the regulation of the profession. His patriotic nation-building purpose had become a commonplace, and if his method was in harmony with historical trends, his execution, despite his evident energy and sincerity, was insufficient to meet the new standards of the profession. Kingsford was shut out. It is regrettable to think that one who did so much as a pioneering civil engineer should be known today primarily as the definitive amateur historian.

William Kingsford was a prolific correspondent for newspapers in Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, and London. Many of his contributions can be found in five volumes of scrapbooks at AO, MU 1628–33. There is no complete bibliography of his publications, but “Bibliography of the members of the Royal Society of Canada,” comp. J. G. Bourinot, RSC Trans., 1st ser., 12 (1894), proc.: 47, and CIHM Reg. are both helpful. Among the most important of his publications are: History, structure and statistics of plank roads in the United States and Canada (Philadelphia, 1852); Impressions of the west and south during a six weeks’ holiday (Toronto, 1858); The Canadian canals: their history and cost, with an inquiry into the policy necessary to advance the well-being of the province (Toronto, 1865); A Canadian political coin: a monograph (Ottawa, 1874); Mr. Kingsford and Sir H. Langevin, C.B.: the case considered with the official correspondence; a memoir for the historian of the future (Toronto, 1882); Canadian archaeology: an essay (Montreal, 1886); The history of Canada (10v., Toronto and London, 1887–98); The early bibliography of the province of Ontario . . . (Toronto and Montreal, 1892); “Sir Daniel Wilson, (died, 6th August, 1892),” RSC Trans, 1st ser., 11 (1893), sect.ii: 55–65; and “Reply of Doctor Kingsford to the strictures on volume VIII. of The history of Canada in the Review of Historical Publications Relating to Canada,” Queen’s Quarterly (Kingston, Ont. ), 5 (1897–98): 37–52.

The entry for Kingsford in the DNB should be used with caution. His important career as a civil engineer awaits study. A photograph was published in “Decease of fellows – the historian Kingsford and the poet Lampman,” RSC Trans., 2nd ser., 5 (1899), proc.: xxiv–xxxi.

ANQ-M, CE1-63, 29 mars 1848. AO, MU 455, Kingsford to William Buckingham, 5 Sept. 1892. DUA, Dalhousie Univ., Senate minutes, 1895–96. Guildhall Library (London), ms 10422/A (St Lawrence Jewry, London, parish reg., 19 Jan. 1820). McGill Univ. Arch., RG 4, c.6, 13 Dec. 1895. McGill Univ. Libraries, Dept. of Rare Books and Special Coll., large mss, William Kingsford. Musée du Château Ramezay (Montreal), Alfred Sandham, “Montreal illustrated,” 3: 101. NA, MG 27, I, E17, general corr., Kingsford to J. R. Gowan, 8 April 1889; MG 29, A10; B1, 26; D61: 4603; D98, Kingsford to Charles Belford, 28 Nov. 1864, 3 May 1865; E15, 4, file Cosmic time, 1884–85; E29: 3300–3; RG 5, B9, 73, no.2346; RG 11, A1, 18; B1(a), 205–12; B1(b), 723–65. UTFL, ms coll. 106. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1890, no.18, app. 19, Rev. of Hist. Pubs. Relating to Canada (Toronto), 1 (1896): 10–19; 2 (1897): 18–23; 3 (1898): 18–20. Globe, 30 Sept. 1898. Toronto Herald, 17 April 1848. Queen’s Univ. and College, Calendar (Kingston), 1889–90: 156. C. [C.] Berger, The writing of Canadian history: aspects of English-Canadian historical writing since 1900 (2nd ed., Toronto and London, 1986). M. B. Taylor, “The writing of English-Canadian history in the nineteenth century” (phd thesis, 2v., Univ. of Toronto, 1984), 2: 447–58. J. K. McConica, “Kingsford and whiggery in Canadian history,” CHR, 40 (1959): 108–20.

Cite This Article

M. Brook Taylor, “KINGSFORD, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kingsford_william_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kingsford_william_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | M. Brook Taylor |

| Title of Article: | KINGSFORD, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | July 23, 2025 |