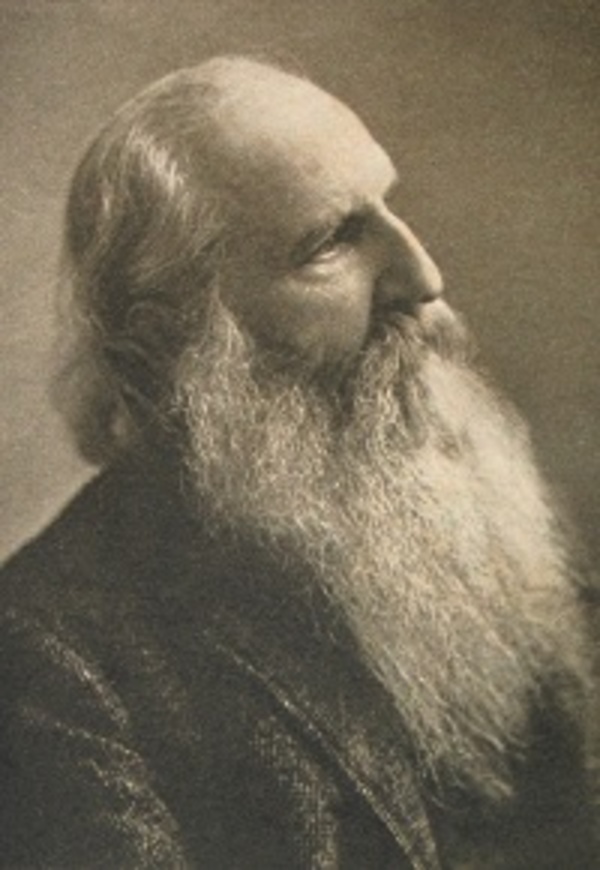

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BUCKE, RICHARD MAURICE, physician, asylum superintendent, and author; b. 18 March 1837 in Methwold, England, seventh of ten children of the Reverend Horatio Walpole Bucke and Clarissa Andrews; m. 7 Sept. 1865 Jessie Maria Gurd in Mooretown, Upper Canada, and they had five sons and three daughters; d. 19 Feb. 1902 in London, Ont.

Richard Maurice Bucke’s family emigrated to Canada in 1838 and settled near London in Upper Canada. Bucke’s early years were spent on the family farm. Instead of receiving formal schooling he was turned loose in his father’s immense library, where he consumed an eclectic intellectual diet, including, significantly, Robert Chambers’s controversial work on evolution, Vestiges of the natural history of creation (London, 1844). Having lost his mother in 1844 and his stepmother in 1853, Bucke left home at the age of 16 and went to work as a labourer in the American Midwest. In 1856, following the death of his father, he joined a covered-wagon train to the far west, arriving on the slopes of the Sierra Nevada late that year. There he joined forces with two young prospectors, Allen and Hosea Grosh. The latter died of blood poisoning within a year, and the former died of exposure after an epic struggle to cross the mountains with Bucke in November–December 1857. As a consequence of that tragic journey, Bucke lost all of one frost-bitten foot and part of the other.

Returning to Canada in 1858 he followed the example of two elder brothers and entered the medical faculty of McGill College, at that time possibly the most advanced medical school in North America. The four-year curriculum included anatomy, chemistry, pharmacology, medicine, surgery, midwifery, and medical jurisprudence. In the final year students acquired practical experience on the wards of the Montreal General Hospital. Bucke excelled at McGill, graduating in 1862 with several prizes, among them one for his thesis, entitled “Correlation of the vital and physical forces.”

Bucke left McGill to study at University College Hospital and King’s College Hospital in London, England. There he came under the influence of Benjamin Ward Richardson, physician to several London hospitals, noted literary figure, and staunch advocate of public health measures. Bucke journeyed to Paris in 1863 and during a four-month sojourn became fluent in French and absorbed much of the scepticism about contemporary therapeutics associated with the Paris clinical school. Of greater importance, however, was his conversion to the philosophy of positivism. Already in England he had read works by Auguste Comte in translation, but during his Paris residence he gamely attacked the prolix volumes of the French sage in their original language. He shared Comte’s belief that a scientific study of human society would allow philosophers to discover universal sociological principles analogous to the natural laws of biology. Questions as to the nature of mind, he learned, were to be answered by the science of medicine rather than by the idle speculations of metaphysicians. Comte’s notion that conventional religion was best replaced by assigning a divine role to collective humanity would be echoed in Bucke’s later work. Finally, in the pages of this thinker, perhaps more so than in the work of Charles Darwin or Herbert Spencer, Bucke found a useful theory of human evolution. In recognition of these contributions to his intellectual development, Bucke in 1863 without hesitation declared Comte “the greatest mind I have ever come in contact with.”

Late that year Bucke returned to Canada and assumed the medical practice of his recently deceased brother, Edward Horatio, in Sarnia. Though his plans were briefly interrupted by a trip to California to testify in the Grosh family’s unsuccessful claim to the famous Comstock silver lode, he eventually opened his office in 1865. During the next decade he worked as a busy general practitioner, and made several journeys to England; in a brief period of ill health he tried his hand at land speculation. In 1876, with the influence of his good friend in the provincial cabinet, Timothy Blair Pardee*, he secured the superintendency of the Asylum for the Insane in Hamilton. He transferred the following year to the London Asylum for the Insane, having been chosen over Dr Stephen Lett to replace the deceased Dr Henry Landor. He thus began a quarter-century of service with this institution.

During his years as a general practitioner in Sarnia, Bucke had lamented his intellectual isolation, observing in a letter to his friend Henry Buxton Forman: “I live here in a state of Egyptian darkness as regards the light from the literary world.” Yet the complaint was misleading, for it was in this period that Bucke developed his lifelong enthusiasm for Walt Whitman and his work. He was introduced to Whitman’s poetry in 1867 by the geologist Thomas Sterry Hunt* and over the next two years came to appreciate the poet’s “extraordinary moral qualities” and to believe he equalled Milton for “grandeur of expression.” In 1877 he travelled to New Jersey to meet Whitman and proclaimed him “an average man magnified to the dimensions of a God”; exposure to him “altered the attitude of my moral nature to everything,” Bucke recorded. He had earlier written to Whitman that his own philosophy was first given coherent form during an illumination in 1872 inspired by the poet’s works. Whitman was astute enough to appreciate that Bucke simply read into his poems “the things that he had been dreaming about”; Bucke himself felt he saw in them meaning which “could never be fully appreciated from the author’s point of view.” In contrast to the impression frequently given by literary scholars, Bucke borrowed little of his philosophy from Whitman, often attempting, instead, to convert the poet to his own way of thinking.

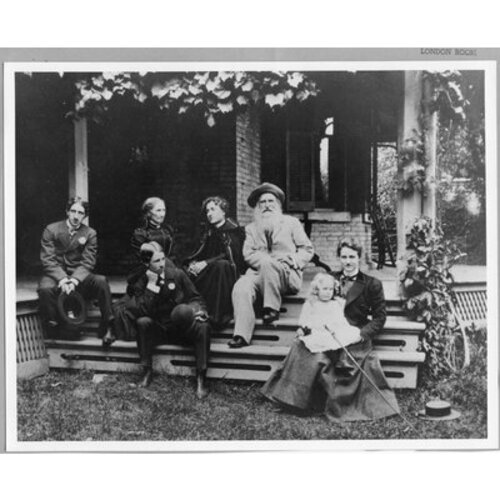

During their 15 years of personal friendship Bucke had nothing but praise for Whitman, enduring public ridicule and his wife’s marked displeasure at his close association with the unorthodox and controversial poet. The two men corresponded several times a week, Bucke journeyed to New Jersey on a number of occasions, and Whitman spent almost four months with the Bucke family in 1880 while Bucke began his biography of the poet. As Whitman’s health deteriorated dramatically from the mid 1880s, his relationship to Bucke became increasingly that of patient to physician. Indeed, the poet commented to his friend Horace L. Traubel, it was only in a medical context that one could “thoroughly know, comprehend” Bucke. Whitman’s gradual decline, marked by brief missives on bowel function and dietary intake, Bucke found a trying experience, and the end, in 1892, must have come as a relief. He then assumed his role as one of his friend’s executors.

If literature and philosophy were, for Bucke, a consuming passion, he was none the less charged with the daily administration and medical supervision of one of North America’s largest asylums. Founded in 1870, the London asylum housed over 900 patients together with their attendants in a complex of buildings which, Bucke declared in 1883, “almost reached the magnitude of a town.” The patients, approximately half men and half women, were usually from the lower strata of the working poor. Once incarcerated, almost 50 per cent remained in the institution for more than ten years. Indeed, discharges in many years barely exceeded the number of deaths in the asylum. Despite constant attempts to contain costs, expenditures rose steadily from 3.1 per cent of the provincial budget in 1878 to 3.6 per cent by 1893. Given the accumulation of chronic cases and the increase in the cost of their care, Bucke became less a medical practitioner than an overburdened administrator. Cloistered with his charges on the asylum grounds and subject to the same daily routines, he gradually came to share what he referred to as “the horribly monotonous life of the patients.”

Bucke recognized the reality of chronicity, declaring that “insanity is essentially an incurable disease.” His treatment reflected this conviction and differed little from that of most Victorian alienists. Designed to hasten and encourage spontaneous recovery, it consisted of sound diet, useful daytime employment, constructive amusement, and regular religious observances. Yet Bucke did depart from orthodox therapeutics in several respects. First, by 1882 he had abandoned the medicinal use of alcohol, departing from the practice advocated, for example, by Dr Daniel Clark* of the Toronto asylum and endorsed to varying degrees by many physicians at the time. Secondly, apparently under the urging of his assistant, Dr Nelson Henry Beemer, by 1883 he had discontinued most forms of physical restraint and initiated an open-door policy allowing the majority of patients free access to the hospital grounds. Most large asylums of the period had yet to grant patients the same degree of freedom, but similar practices would soon be adopted by Drs William George Metcalf* and Charles Kirk Clarke* of the Rockwood Asylum in Kingston. Finally, Bucke was convinced that, in certain cases of insanity, surgery might provide a cure. His first venture into surgical treatment involved the use of a minor procedure to inhibit masturbation, then generally assumed to be a common cause of mental illness. After 21 procedures in 1877, Bucke could show no therapeutic benefits and was forced to concede that in most patients the “solitary vice” was more likely a symptom than a cause of the illness. His next foray into surgical treatment did not occur for 18 years.

In 1895 Bucke launched an attempt to cure female patients through gynaecological surgery. According to the widely accepted notion of reflex action, disease in one part of the body was capable of producing symptoms in a distant region. Nowhere did Victorian physicians find greater confirmation of this theory than in the widely held belief that pelvic disease in women might induce mental aberrations. What propelled Bucke beyond a quiet acceptance of this theory to direct surgical therapy was the fortuitous appointment of an assistant with a keen interest in gynaecological surgery, Dr Alfred Thomas Hobbs. Many of the asylum’s women residents doubtless did suffer from annoying and debilitating gynaecological conditions. Some would have borne the scars of the crude obstetrical care which characterized the period. Still others may have suffered the consequences of venereal diseases, then prevalent. Finally, some patients must have exhibited minor anatomical anomalies later recognized as benign but at the time considered pathological. Thus it was not surprising that when Bucke and Hobbs examined their typical female patient – a married woman in her mid thirties who had borne children – they found apparent disease in 85 per cent of cases.

Of the first 19 patients operated upon, almost two-thirds showed, according to Bucke, an unexpected post-operative mental improvement or recovery. Over a five-year period, 228 women underwent procedures, the most common being uterine suspension (24 per cent), dilatation and curettage (21 per cent), cervical amputation (16 per cent), and perineal repair (14 per cent). Despite Bucke’s claims, however, a comparison of his patients with age-matched controls fails to demonstrate that the operations had any psychiatric benefit. The findings of Bucke and Hobbs doubtless reflect observer bias: they very much wanted a successful outcome. Quite apart from a genuine desire to cure their patients, they were acutely aware that the field of psychiatry languished behind other areas of 19th-century medicine. By incorporating the advances of the new antiseptic surgery and suggesting an important explanatory role for the recently discovered “internal secretions” or hormones, they sought to give modernity and status to their neglected discipline. It is this professional concern rather than Victorian theories of gender – which their numerous medical critics certainly shared – that best explains the gynaecological enthusiasms of Bucke and Hobbs.

While serving as asylum superintendent, Bucke at last gained the time to commit to paper his literary and philosophical speculations. The result, Man’s moral nature, appeared in 1879 and advanced two basic arguments. First, Bucke believed that human beings possessed an innate moral sense which resided in that portion of the autonomic nervous system known as the sympathetic nervous system. The concept was an anachronistic one based on French physiology of the 1820s and argued from anatomical inference rather than experimental evidence. Yet the attempt to localize specific mental functions to precise neurological sites, and the use of associationist psychology borrowed from Alexander Bain or Herbert Spencer, was entirely congruent with the major currents in Victorian medicine. The second thesis advanced by Bucke held that this innate moral sense was increasing. To support his view he used evolutionary theory and the recapitulation hypothesis popularized by Ernst Haeckel, which maintained that the human race evolved as a collectivity in a fashion similar to a child’s passage to maturity. Though Bucke considered his work “a very remarkable and valuable book,” only four copies were sold in England during its first year in print, and a scant 241 copies were purchased in North America during the four years after publication. None the less, as the first Canadian monograph on neuropsychiatry it remains a literary landmark.

Over the next two decades Bucke published his biography of Whitman as well as numerous papers on psychiatry, and he participated in commemorative publications following Whitman’s death. Throughout this period he collected evidence and theories for what would be his most significant work, Cosmic consciousness (Philadelphia, 1901). On a personal level, the book allowed him once again to pay tribute to Whitman while also giving coherence to his own illumination experience of 1872. In an intellectual sense, the volume assumes importance not as a classic of mysticism but as a specific example of psychological medicine’s attempt at the end of the 19th century to grapple with an emerging awareness of the unconscious mind. If to later readers his work would appear largely religious in tone and intent, to Bucke himself it was a study of mental physiology and psychology; it did not concern itself with the supernatural, and its subject could, he asserted, “be studied with no more difficulty than other natural phenomenon.”

Many of the ideas expressed in the introduction to the new volume were found in Bucke’s previous work. Once again he argued for an evolutionary view of the human mind. Borrowing from George John Romanes, the British zoologist-psychologist, he held that the mind had gradually developed through three levels beginning with the simple registration of sensations, progressing to an animal-like “simple consciousness,” and finally arriving at modern “self consciousness.” Bucke’s contribution to this theory was to add a new stage of mental evolution, termed “cosmic consciousness,” which implied “a consciousness of . . . the life and order of the universe” and was accompanied by “intellectual enlightenment” and “a state of moral exaltation.” The bulk of his book was composed of case studies of some 50 men who were said to have possessed the faculty, including Jesus, Muhammad, Buddha, Dante, Francis Bacon, Bucke himself, and of course Whitman. Bucke was convinced that cosmic consciousness, rare in previous centuries, was on the increase and would one day be present in all human beings. Endowed with such cosmic insight, people would no longer require the trappings and doctrines of conventional religion. For Bucke, as for Auguste Comte, God was nothing more or less than collective humanity.

Like most of Bucke’s writings, Cosmic consciousness rested on common Victorian beliefs, but the conclusions drawn were idiosyncratic. The seeming mystical eccentricity of the work should not be allowed to obscure the context in which it was conceived. Two late-19th-century intellectual currents are of particular relevance. First, Bucke was thoroughly familiar with the work of the Society for Psychical Research, a group which numbered among its members Alfred Russel Wallace, William James, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and Pierre Janet. The empiricism of this group, manifested in sophisticated studies of telepathy and clairvoyance, stripped spiritualism of its supernatural connotations. Secondly, with the legitimation of hypnosis as a focus of medical interest by Jean-Martin Charcot, Europe’s leading neurologist, in 1882, the floodgate was opened to a growing volume of work by physicians on disorders and attributes of the dynamic unconscious. If to subsequent generations Bucke’s work, particularly Cosmic consciousness, appears largely religious, to his contemporaries it must have seemed little different from the early writings of Jung, Janet, or Freud.

Sadly, Bucke did not live to see the success of his last book, which, in the next three-quarters of a century, would be reprinted over 20 times. In February 1902 he paused to gaze at the winter stars, lost his balance, and died from the resulting head injury. But for his untimely demise he, rather than Ernest Jones, might well have become Freud’s champion in Canada, and he certainly would have lent his voice to the early mental hygiene movement. As it was, his career ranged from high adventure on the western frontier, through study in the universities and salons of London and Paris, to participation in the avantgarde of American literature. Though often an enigmatic individual of eccentric views, Bucke garnered many honours and offices. He was elected a charter-member of the Royal Society of Canada in 1882, was appointed first professor of nervous and mental diseases at Western University of London, Ontario, the same year, became president of the British Medical Association’s psychological section in 1897, and the following year was elected president of the American Medico-Psychological Association.

Such recognition from his contemporaries suggests that, while Bucke was certainly unconventional, the intellectual issues he identified as important and the philosophical tools by which he sought to fashion a coherent world-view were very much in the Victorian mainstream. His literary activities, his metaphysical speculations, and his clinical theory constituted for Bucke a seamless whole. The philosophy he endorsed was woven of evolutionary naturalism, Whitman’s poetry, positivism, associationist psychology, and theories of neurological localization. If his proselytizing on behalf of Whitman and his seemingly far-fetched speculations on cosmic consciousness dominated his later years, he is none the less best recalled as a compassionate Victorian psychiatrist and as Canada’s first theorist of neuropsychiatry.

In addition to Man’s moral nature: an essay (New York and Toronto, 1879) and Cosmic consciousness: a study in the evolution of the human mind (Philadelphia, 1901), major publications by Richard Maurice Bucke include Walt Whitman (Philadelphia, 1883) and the report of his gynaecological experiments, “Two hundred operative cases – insane women,” American Medico-Psychological Assoc., Proc. (n.p.), 1900: 99–105. His md dissertation, “The correlation of the vital and physical forces . . . ,” appeared in the British American Journal (Montreal), 3 (1862): 161–67, 193–200, and 225–33. Bibliographies of his writings are available in Richard Maurice Bucke: a catalogue based upon the collections of the University of Western Ontario Libraries, comp. M. A. Jameson (London, 1978), and as an appendix to J. H. Coyne, “Richard Maurice Bucke – a sketch,” RSC Trans., 2nd ser., 12 (1906), sect.ii: 159–96.

Bucke’s correspondence with Whitman and his circle has been published as Richard Maurice Bucke, medical mystic: letters of Dr. Bucke to Walt Whitman and his friends, ed. Artem Lozynsky (Detroit, 1977).

AO, RG 10, 20-C-1; RG 63, A-1. Univ. of Western Ont. Library, Regional Coll. (London), R. M. Bucke papers. Sarnia Observer and Lambton Advertiser (Sarnia, [Ont.]), 14 Sept. 1865. M. L. Barr, A century of medicine at Western: a centennial history of the faculty of medicine, University of Western Ontario (London, 1977). Cook, Regenerators. J. R. Home, “‘Cosmic consciousness – then and now’: the evolutionary mysticism of Maurice Bucke” (phd thesis, Columbia Univ., New York, 1964); “R. M. Bucke: pioneer psychiatrist, practical mystic,” OH, 59 (1967): 197–208. C. L. Krasnick, “‘In charge of the loons’: a portrait of the London, Ontario, Asylum for the Insane in the nineteenth century,” OH, 74 (1982): 138–84. Wendy Mitchinson, “Gynecological operations on insane women: London, Ontario, 1895–1901,” Journal of Social Hist. (Pittsburgh, Pa), 15 (1982): 467–84; “R. M. Bucke: a Victorian asylum superintendent,” OH, 73 (1981): 239–54. Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers, annual reports of the medical superintendent of the London asylum in the reports of the inspector of prisons and public charities, 1877–81, and annual reports upon the lunatic and idiot asylums, 1882–1902/3. Edwin Seaborn, The march of medicine in western Ontario (Toronto, 1944). S. E. D. Shortt, “The myth of a Canadian Boswell: Dr. R. M. Bucke and Walt Whitman,” Canadian Bull. of Medical Hist. ([Quebec]), 1 (1984), no.2: 55–70; Victorian lunacy: Richard M. Bucke and the practice of late nineteenth-century psychiatry (Cambridge, Eng., 1986). H. B. Timothy, “Rediscovering R. M. Bucke,” Western Ontario Hist. Notes (London), 21 (1965), no.1 : 34–40.

Cite This Article

S. E. D. Shortt, “BUCKE, RICHARD MAURICE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bucke_richard_maurice_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bucke_richard_maurice_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | S. E. D. Shortt |

| Title of Article: | BUCKE, RICHARD MAURICE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | July 25, 2025 |