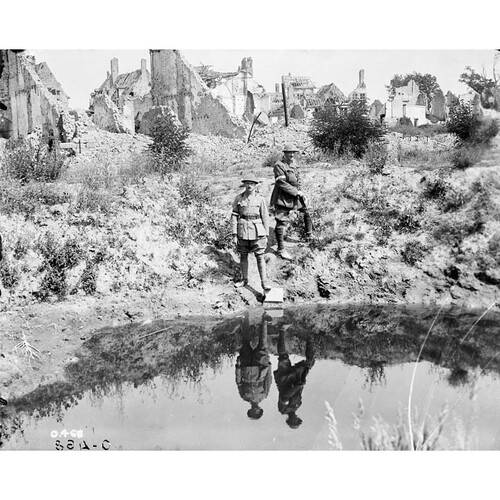

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

PAPINEAU, TALBOT MERCER, lawyer and army officer; b. 25 March 1883 in Montebello, Que., second of the four sons of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Caroline Rogers; great-grandson of Louis-Joseph Papineau*; d. unmarried 30 Oct. 1917 in Passchendaele (Passendale), Belgium.

Talbot Mercer Papineau was a beau idéal of his generation: handsome, clever and athletic, a gifted orator and writer, impeccably bilingual, and possessed of a charismatic personality. His brief life continues to symbolize all the bright promise cut down by World War I. Although he bore one of Quebec’s most famous surnames, his lineage was largely American and his upbringing mainly in English. The dominant influence of his childhood was his strong-willed and ambitious mother, a member of a prominent family from Philadelphia. Papineau was brought up a Protestant and he was educated at the High School of Montreal and at McGill University. Yet he described himself as a “French Canadian” and his boyhood at Montebello, in the Papineau family’s seigneury of Petite-Nation, instilled in him an attachment to the Quebec landscape that was close to metaphysical.

In 1905 Papineau received one of the first Rhodes scholarships awarded to a Canadian. He read law at Brasenose College, Oxford, achieved a second, and rowed stroke for the college eight. After returning to Montreal in 1908, he set up a law practice and began a career in public life. Thus far, his political ideas were eclectic; a strong believer in free trade, he was also a member of the Montreal chapter of the Round Table, a forum on imperial federation [see Edward Joseph Kylie]. Probably through the influence of his cousin Henri Bourassa*, who founded Le Devoir in 1910, Papineau also began to cultivate an interest in Quebec culture. The most concrete expression of his developing political philosophy is found in a letter written in October 1915. “Especially, I want to see Canadian pride based on substantial achievements, and not on the supercilious and fallacious sense of self-satisfaction we have borrowed from England.”

At the outbreak of war in August 1914 Papineau rushed to enlist in the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry [see Charles James Townshend Stewart]. His reasons for volunteering were straightforward. The war was both an adventure and the educated bet of a careerist. Although he had never joined the militia, he was well aware that a good service record would further his political fortunes.

Papineau was instantly commissioned a lieutenant. He proved to be both resourceful and mettlesome. He received one of the first Military crosses of the war to be awarded to Canadians for his role as co-leader of a successful raid at Saint-Eloi (Sint-Elooi), Belgium, during the night of 27–28 Feb. 1915. By May of that year, having survived the battle of Frezenberg Ridge, in which his regiment suffered massive losses, he was the only officer of the original complement not to have been killed, wounded, or sent off sick. That summer, promoted captain, he embarked on one of the most remarkable correspondences engendered by the war, with a young woman he had never met, a sculptor in Philadelphia named Beatrice Fox. As he later said, he was in search of a relationship that could be “absolutely natural and free from the artificialities which surround so generally the intercourse between men and women.” Nearly all of his letters are preserved, along with those he wrote almost daily to his mother. His style is alive and assured, his observations acute, his accounts of his own feelings candid and unsparing, as is illustrated in a passage dated 5 Aug. 1915. “I hate this murderous business. I have seen so much death. . . . Never shall I shoot duck again, or draw a speckled trout to gasp in my basket – I would not wish to see the death of a spider.”

In February 1916, through the influence of Sir William Maxwell Aitken*, head of the Canadian War Records Office, Papineau became a staff officer. That June he was seconded to the staff of the War Records Office, based at the headquarters of the Canadian Corps in France. His duties included writing press communiqués and directing photographers and cinematographers. At this time, he also continued to develop his political ideas. “The issue in Canada after the war is going to be between Imperialism and Nationalism,” he wrote to Beatrice Fox on 16 March 1916. “My whole inclination is towards an independent Canada with all the attributes of sovereignty, including its responsibilities.”

Papineau’s single contribution to public debate also dates from this period. As early as 1915 he had described the second battle of Ypres as “the birth-pangs of our nationality.” Yet within Canada, because of Quebec’s reluctance to participate, the war had become a bitterly divisive issue. To Papineau’s anger, the principal voice opposed to the war was that of his cousin Bourassa. Papineau’s challenge took the form of an open letter to Bourassa, published first in the Montreal Gazette on 28 July 1916. “As I write, French and English Canadians are fighting and dying side by side,” said the most eloquent passage. “Is their sacrifice to go for nothing or will it not cement a foundation for a true Canadian nation, . . . independent in thought, independent in action, independent even in its political organization – but in spirit united for high international and humane purposes to the two Motherlands of England and France?” Elsewhere in his letter, he expressed the political course he intended to follow once the war was ended. “As a [French] minority in a great English-speaking continent, . . . we must rather seek to find points of contact and of common interest than points of friction and separation. We must make certain concessions and certain sacrifices of our distinct individuality if we mean to live on amicable terms with our fellow citizens or if we expect them to make similar concessions to us.”

Bourassa’s reply to Papineau was published a week later. Much of his argument was ironic and ad hominem, but he made some telling points. Opposed to the war because he was opposed to imperialism and its exploitation of people, he drew parallels between the sufferings of the Belgians at the hand of the Germans and those of Franco-Ontarians under Regulation 17 [see Sir James Pliny Whitney]. “To preach Holy War for the ‘liberties of peoples’ overseas, and to oppress the national minorities within Canada is, in our opinion, nothing but odious hypocrisy.”

In the short term, Papineau won most of the honours. Overnight he became a national hero. He also gained a certain international reputation. On 22 Aug. 1916 the London Times reprinted his letter almost entirely, under the heading “The soul of Canada.” These cousins defined with eloquence the terms of a debate about the character of their country which could be reprinted virtually unchanged today.

In June 1917, shortly after the battle of Vimy Ridge, Papineau returned to active service with the PPCLI as the commander of a company. So far as can be judged from his letters, this decision was motivated by an inseparable blend of patriotism and ambition. As a staff officer, he had been nagged by a sense of guilt. “More friends have gone,” he wrote to Beatrice Fox on 30 Sept. 1916. “By what strange law am I still here? What right have I to selfish pleasure any longer?” Calculation impelled him as well. As the commanding officer of the PPCLI, Lieutenant-Colonel Agar Stewart Allan Masterton Adamson*, wrote to his wife, Ann Mabel Cawthra*, on 11 May 1917, Papineau “intended to go into public life after the war and thought that he would have a better chance . . . if he could show he had been with the Regiment through some big push like the last one.”

Papineau was promoted acting major in August 1917. Late that October the regiment was moved to Passchendaele as the spearhead of an assault. It attacked at 6:00 a.m. on 30 October. Papineau’s last recorded words before going over the top, spoken to Major Hugh Wilderspin Niven, were “You know, Hughie, this is suicide.” He was hit by a shell as he left the trench.

Without doubt, memorialized the Ottawa Citizen, he had been destined to fill a high place in public life. “Many people who had no personal acquaintance with him regarded him as the one man specially fitted to lead in the task of reconciling the two races.” In Britain, the Daily Mail saluted him as “A lost leader.” In the absence of tangible achievements, it is difficult to assign him his proper place in history. No other figure provides a more arresting metaphor for Canada during the war years: the reality of promise unfulfilled; the burgeoning of Canadian nationalism, but also the widening gap between the two cultures. “Nearly 35 I am, and very little or nothing done,” Papineau wrote to his mother shortly before the battle of Passchendaele. Yet he was wrong. His remarkable letters from the front are the Canadian voice of World War I, a reminder of all that was lost there.

Talbot Mercer Papineau’s open letter to Henri Bourassa was republished along with Bourassa’s reply and other related material in a pamphlet entitled Canadian nationalism and the war (Montreal, 1916). A speech delivered by Papineau in 1917 appeared posthumously under the title The war and its influences upon Canada . . . ([Montreal, 1920]).

NA, MG 30, E52; E149. Sandra Gwyn, Tapestry of war: a private view of Canadians in the Great War (Toronto, 1992). Ralph Hodder-Williams, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, 1914–1919 (2v., London, 1923). Mason Wade, The French Canadians, 1760–1967 (rev. ed., 2v., Toronto, 1968), 2. Jeffery Williams, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (rev. ed., London, 1985).

Cite This Article

Sandra Gwyn, “PAPINEAU, TALBOT MERCER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/papineau_talbot_mercer_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/papineau_talbot_mercer_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sandra Gwyn |

| Title of Article: | PAPINEAU, TALBOT MERCER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | November 6, 2025 |