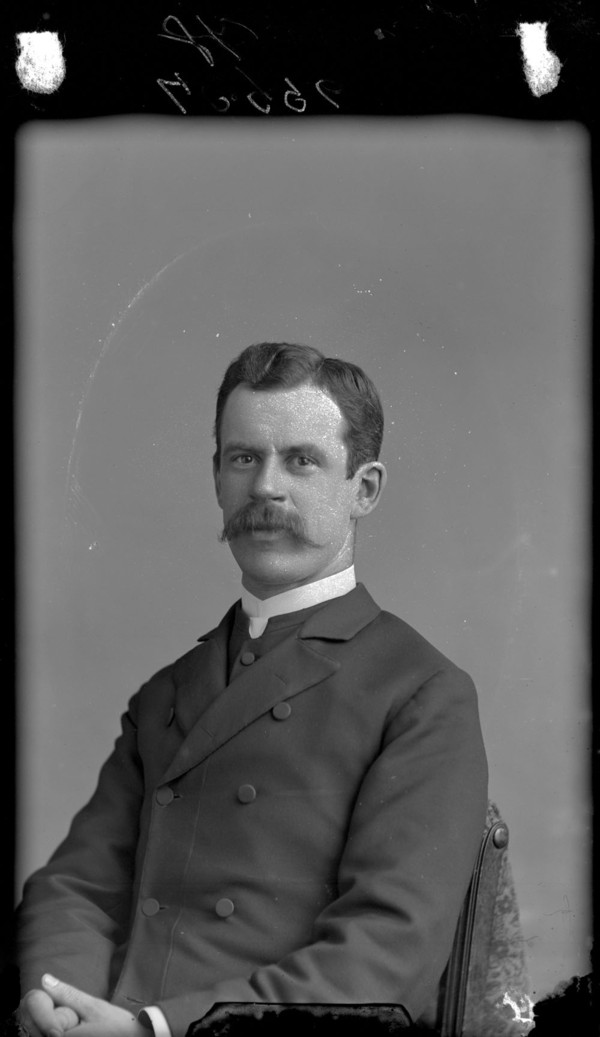

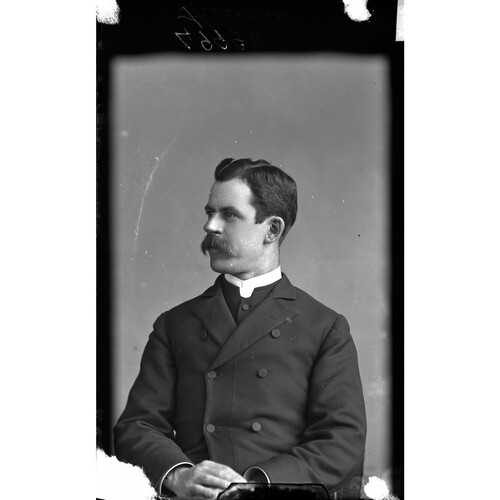

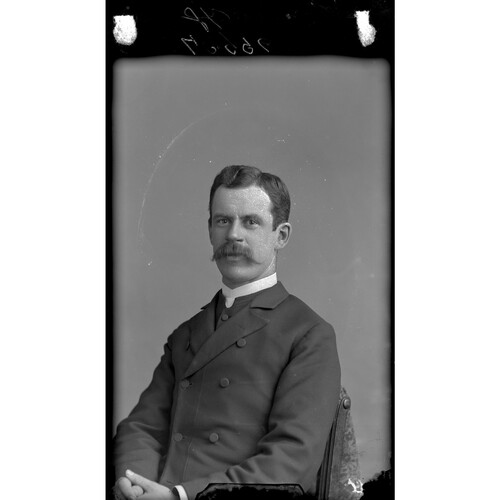

SHEARER, JOHN GEORGE, Presbyterian minister and reformer; b. 9 Aug. 1859 near Bright, Upper Canada, son of John Shearer and Margaret ———; m. 8 Aug. 1883 Elizabeth A. Johnson in Northfield (Northfield Centre), Ont.; they had no children; d. 27 March 1925 in Toronto.

One of the most tireless moral reformers Canada has ever had, John G. Shearer was born to Scottish settlers on a farm in an area of Oxford County known for its evangelical Presbyterianism. He attended the public school in Ratho, the high school in Weston (Toronto), and the collegiate institute in Brantford. He went into teaching but in 1883, following a conversion experience, he decided to enter the Presbyterian ministry. He began preaching in Onondaga, near Brantford, and later worked as a missionary in Fort William (Thunder Bay) and then in Toronto. It was there, as a student at Knox College, that he witnessed the realities of inner-city poverty and vice and began to see city missions as a means to spiritual and moral regeneration. In the Knox College Monthly of November 1886, he and a fellow student described mission work in Toronto, with Shearer reviewing the Elizabeth Street mission supported by the Central Presbyterian Church. He graduated from Knox in 1888; ordained on 5 June of that year, he took up parish work in Caledonia. During his time there he continued his studies, earning a ba from the University of Toronto in 1889. Two years later he moved to Erskine Presbyterian Church in Hamilton.

Shearer soon became active in nation-wide efforts to keep Canada morally “pure,” in which cause he demonstrated tremendous zeal and organizational talent. He was particularly strong in his commitment to the Ontario branch of the Lord’s Day Alliance, a group formed in 1888 to secure laws to uphold what it called “the English Sunday.” In The workingmen and the weekly rest day (Toronto), a pamphlet written about 1896, Shearer attempted to align the interest of labour with Christian moral reform. In 1899 the Presbyterian Church in Canada selected him to convene its committee on sabbath observance and legislation.

The following year Shearer left the ministerial field to become the first general secretary of the dominion Lord’s Day Alliance, based in Toronto. Its Sabbatarian focus became a pressing concern for evangelical Christianity when decisions by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in 1903 and 1905 nullified Sunday laws in Ontario. Shearer provided pressure. In 1903 he had founded a promotional serial in Toronto, the Lord’s Day Advocate. The Alliance succeeded in its main aim with the passage of the federal Lord’s Day Act in 1906, and subsequently devoted its efforts to ensuring the enforcement of the law by local police. In Toronto, for instance, charges under the act constituted the largest group of offences reported in the years before World War I. Many of these charges involved prosecuting Chinese and Jewish vendors, among them vegetable sellers on Spadina Avenue. The Alliance insisted that if Jews wanted to immigrate to Canada, they had to abide by English/Scottish customs regarding Saturdays and Sundays. “A number of Jews in Toronto, at Englehart, and other places, who have found asylums and home comforts in Canada when driven by persecution from other lands,” the Alliance noted in its report for 1911, “do not scruple to break our laws while enjoying the protection they afford them.”

Sunday observance, temperance, and the fight against prostitution, probably the main three interests of Protestant Canada’s moral reform movement, absorbed much of Shearer’s time and energy. In 1907, the same year that he had been granted a dd by Knox, he was asked by the Presbyterian General Assembly to head up a department similar to the Methodists’ Board of Temperance, Prohibition, and Moral Reform, run by Samuel Dwight Chown*. Leaving the Alliance, Shearer initially set up a standing committee on temperance and other moral and social reforms. The work of this body, which was organized as the Board of Moral and Social Reform in 1908 and renamed the Board of Social Service and Evangelism in 1911, was more evangelical and less influenced by modern approaches to social reform than Chown’s. (The Methodists, among other programs, offered courses in sociology and classes in sex hygiene.) To fulfil his mission, Shearer toured the country denouncing red-light districts, obscene literature, and the “demon rum.” Such sweeps were characterized less by modern sociological analysis and rescue work than by Shearer’s talent for sensationalist revelation and thunderous denunciation, and his undeviating faith in law enforcement and imprisonment. One “vice tour” led him in 1910 to Winnipeg, where he singled out the involvement of Asians in the so-called white slavery traffic, though the only Chinese uncovered by a subsequent provincial commission on prostitution in Winnipeg were those doing housework in brothels.

On 31 Oct. 1907, in Toronto, Shearer and Thomas Albert Moore*, the social service secretary of the Methodist Church, had founded the interdenominational Moral and Social Reform Council of Canada (renamed the Social Service Council of Canada in 1913). In 1912 Shearer was selected to head one of the council’s most active subcommittees, the National Committee for the Suppression of the White Slave Traffic. In this capacity he led lobbies that resulted in criminal-law amendments against prostitution and procurement. He also represented Canada in the international movement against white slavery led by British journalist William Thomas Stead.

Possessed of narrow views, Shearer fit the stereotype of the crusading moralist keen on prohibiting pleasure and oblivious to people’s welfare. “Immoral” literature was thus one of his concerns as well. In 1909 the Moral and Social Reform Council joined with Toronto deputy police chief William Stark in successfully lobbying the federal government to strengthen the Criminal Code and consequently to facilitate prosecutions for the sale and distribution of obscene material. In cooperation with his American counterpart Anthony Comstock, Shearer campaigned to enforce the new legislation by targeting such booksellers as Leonard James Skill of Toronto, who was charged after repeated seizures of his books by the Department of Customs. Prior to imposing sentence in this case, the judge opined that the most “poisonous” literature originated in France. Shearer was also influential when, in 1911, Toronto police laid charges against several other prominent booksellers, including Albert Britnell, for selling Sir Richard Francis Burton’s unexpurgated translation of Arabian Nights’ entertainments and short stories by Guy de Maupassant and Honoré de Balzac – all of which were ordered burned by police magistrate George Taylor Denison and placed on the list of publications prohibited entry into Canada.

The tenor of Shearer’s enforcement efforts in all of these areas is captured in an article he had written for the Dominion Presbyterian in 1906: “We may not want to copy the Puritans in every particular, but, in their respect for righteousness, law, order, religion, and the Lord’s Day, we could stand a good deal more Puritanism than we are getting. . . . Let [our] Puritanism be that of the twentieth century – wise, tolerant, gracious, and inflexible . . . let us go ahead in the present crusade unterrified by all sneering cries of ‘puritanical legislation’ raised by cavilling newspapers that would cater to an evil-minded crowd.”

Like many of his Presbyterian colleagues, notably George Campbell Pidgeon*, Shearer maintained that evangelism – a fundamental dedication to Jesus – must be accompanied by reform. This linkage, so central to Shearer’s theology, was strongly evident in the report he and Thomas Buchanan Kilpatrick wrote on their evangelistic campaign in the Kootenay region of British Columbia in 1909. Their efforts had failed, they concluded, because of strong local disregard for the Lord’s Day, the power of liquor and brothels, and the undermining absence of social restraint. According to historian Brian J. Fraser, the campaign “found its most responsive audience among those middle-class community leaders already connected with the church who were seeking to legitimate and defend their moral, social, and religious values in a pioneer community.”

By 1912, in the debate within the rising Social Gospel movement over the relation between Christianity and socialism, the puritanism of Shearer’s concepts of social welfare was being modified by his increasing progressivism. Shearer’s theories of social regeneration were far from original, but when delivered with his customary fire, they conveyed a potent message. He had long argued for his church’s involvement in urban problems. In June 1913, at the Presbyterian congress at Massey Music Hall in Toronto, his stirring address on “Redemption of the city” highlighted the hellish impact of urbanization and the need for the social and spiritual reclamation of inner-city folk. Moved by vigorous applause, he asked, “At the peril of the Kingdom of Jesus Christ in Canada, at the peril of the very life of the Church in Canada, shall we neglect to redeem our cities?”

To meet this goal Shearer, through the Board of Social Service and Evangelism, devoted much effort and money to establishing settlement houses in major Canadian cities (starting with St Christopher House in Toronto in 1912), funding local social and moral agencies, and investigating weak police work. Wherever success was achieved, from Halifax to Saskatoon, the much-travelled Shearer was there to trumpet, in the press and public addresses, the eradication of “recognized public vice.” Within his own church, however, his demands for increased funding for the board produced a financial crisis in 1913 that led the General Assembly to direct its amalgamation with the Board of Foreign Missions the following year.

Undeterred, in 1914 Shearer and T. A. Moore took leading roles in organizing the seminal Social Service Congress in Ottawa. In his introduction to its published report, Shearer’s long-time friend and Social Service Council president Charles William Gordon* placed at the feet of government and big business the responsibility for the dismal living conditions of many urban and farm dwellers. In 1917 Shearer’s membership in the Presbyterian commission on the war, which expressed profound dissatisfaction with conventional religion and intense commitment to social reform, confirmed this vice warrior’s dual focus. Two years later he would express sympathy with the United Farmers of Ontario and the participants in the Winnipeg General Strike, a move that likely alienated him from many Presbyterian colleagues and aligned him more with Methodism’s progressive sector. In discussing the strike he lamented that “workers had to resort to wrong tactics to secure a correct principle.”

The Social Service Council, which increasingly was Shearer’s preferred vehicle for social uplift and for which he worked full-time as general secretary from June 1918, was never a radical organization. It shunned direct association with labour’s left wing, and workers were largely indifferent to Presbyterian moralizing. Unlike some Social Gospellers, Shearer refused to consider leaving the church in order to pursue his concerns with wealth and poverty, housing, and working conditions. By 1918 the council’s influence and organizational strength were peaking. A federation of leading social-work bodies, it had a full range of representation, including the major religious denominations, agrarian associations, and purity-education and temperance groups. The council’s most lasting venture was probably the magazine Shearer founded in 1918, Social Welfare, Canada’s first major publication in the emerging but largely unprofessionalized field of social work. Ever alert to bright recruits, in July 1918 he hired Charlotte Elizabeth Hazeltyne Whitton* as assistant editor and assistant secretary, responsible for handling the council’s office in Toronto and liaising with welfare agencies there. Whitton found Shearer, a severely stern man to many, quite amiable – she called him “Mr. Greatheart” – and a hard but understanding taskmaster. After his death in March 1925 and the loss of his sustaining drive, the council seems to have declined to the point of oblivion.

It is not unfair to conclude that the Reverend John G. Shearer had spearheaded the most conservative wing of the social purity/social gospel movement of the early 20th century – conservative theologically, sexually, and racially. Nevertheless, after the war he appeared to move with the times, not just in the direction of the Social Gospel, but also in breaking with the most evangelical wing of Canadian Presbyterianism, the wing that rejected church union. Shearer distanced himself from many fellow ministers as a result of his belief that moral and social reform could be accomplished best through a union of resources. (The United Church of Canada would come into being in June 1925.) Though Shearer was widely recognized in Social Welfare and elsewhere as the dean of social service, the Presbyterian Record, despite his national prominence, did not even publish an obituary.

AO, RG 22-305, no.52182; RG 80-5-0-114, no.1180. NA, RG 31, C1, Blandford Township, Ont., 1871, div.2: 40 (mfm. at AO). Canadian annual rev., 1918: 598. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). B. J. Fraser, The social uplifters: Presbyterian progressives and the Social Gospel in Canada, 1875–1915 (Waterloo, Ont., 1988). S. P. Meen, “The battle for the Sabbath: the sabbatarian lobby in Canada, 1890–1912” (phd thesis, Univ. of B.C., Victoria, 1979). Mariana Valverde, The age of light, soap, and water: moral reform in English Canada, 1885–1925 (Toronto, 1991).

Cite This Article

Mariana Valverde and S. Craig Wilson, “SHEARER, JOHN GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shearer_john_george_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/shearer_john_george_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mariana Valverde and S. Craig Wilson |

| Title of Article: | SHEARER, JOHN GEORGE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | July 24, 2025 |