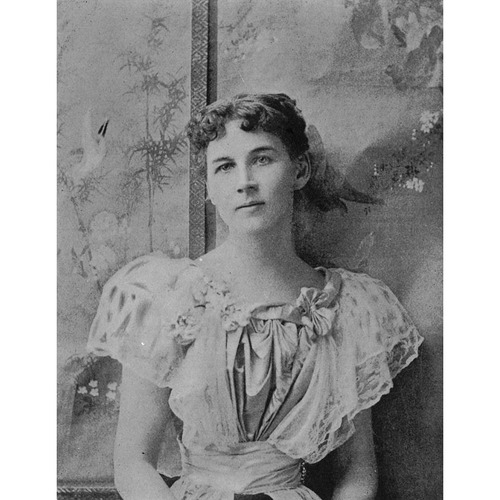

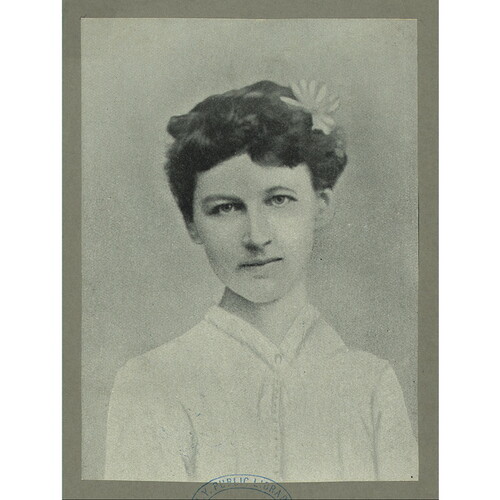

DUNCAN, SARA JEANNETTE (Cotes), known as Garth Grafton, teacher, journalist, and author; b. 22 Dec. 1861 in Brantford, Upper Canada, daughter of Charles Duncan, a dry-goods merchant, and Jane Bell; m. 6 Dec. 1890 Everard Charles Cotes in Calcutta, India; they had no children; d. 22 July 1922 in Ashtead, England.

Sara Jeannette Duncan would have declined the opportunity to begin her own biography with an account of her antecedents. As she wrote in The imperialist (London and New York, 1904), she felt that Canadians defined who they were by their merit and choice of occupation, not by their birth. Nonetheless, her parents were formative influences. Her father, who was born in Cupar, Scotland, immigrated in the 1850s to New Brunswick, where he met his future wife. The two settled in Brantford by 1858 and became parishioners of the legendary Presbyterian minister William Cochrane*. On 18 May 1862 their first daughter was baptized Sara Janet Duncan, the name she would later use for legal purposes (sometimes with the spelling Sarah) and which would appear on her headstone; the Duncans nicknamed her Redney, a name she used only within the family. (She later wrote that she deplored the use of nicknames and diminutives by professional women, which she felt put “an element of incongruity between them and their work, and g[a]ve it a character often undeservedly flippant and frivolous.”)

Like many intellectual women of the day, she trained as a teacher, taking her third-class certificate at the Brantford Model School in 1879 and her second-class certificate at the Toronto Normal School in 1882. Her career in teaching, however, was short. Her first poems appeared in print in 1880 and her first article in 1881. These writings suggest that journalism was her goal even while she worked as a supply teacher in Brantford and nearby towns.

In late 1884 Duncan persuaded John Cameron* of the Toronto Globe to pay her for articles on the upcoming World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial exposition in New Orleans. She headed south in December. Her articles, published under the pseudonym Garth in both the Globe and the London Advertiser (London, Ont.) and reprinted in American papers, were so successful that she was offered a regular column in the Globe when she returned the following spring. Thus began a remarkable journalistic career. After a summer writing a weekly column for the Globe, she moved in the fall of 1885 to Washington, D.C., where by early 1886 she was in charge of the current literature department of the Washington Post and was one of its prominent editorial writers. In the summer of 1886 she took over the “Woman’s World” section of the Globe as a regular member of its editorial staff. She left in November 1887 to work for the Montreal Star and in February she became its parliamentary correspondent in Ottawa.

In May 1885 Duncan had begun making regular contributions to the Globe under the pen-name Garth Grafton. Her column, “Other People and I,” was a precursor to “Woman’s World,” the section created in 1886 for female readers. These columns, a grab-bag of “delicious scraps,” dealt with topics as diverse as life insurance for women, mass-produced interior decor, and the popularity of gilt hairpins. On a more serious note, “Woman’s World” also included interviews with prominent women, among them the Mohawk poet Emily Pauline Johnson* and Dr Alice McGillivray (one of Canada’s first female physicians), and discussed such issues as the new literary realism and its attraction for women readers. She had defined this attraction in June 1885: “The ordinary detail of humdrum life and circumstance, pen-painted by an artist with sympathies keen enough to detect the mysterious throbbing of the life that is inner and under, fascinates us like our own photographs.” Under her own signature Duncan also wrote a column for the Toronto literary periodical Week on the important intellectual issues of the day. These included the effects of Canada’s colonial position on the growth of the arts. “We are well-clad, well fed, well read. Why should we not buy our own books!” she lamented in September 1886. “Our enforced political humility is the distinguishing characteristic of every phase of our national life. We are ignored, and we ignore ourselves.” She went on to condemn Ontarians as a “camp of Philistines” and cited their newspapers as proof: “Politics and vituperation, temperance and vituperation, religion and vituperation; these three dietetic articles, the vituperative sauce invariably accompanying, form the exclusive journalistic pabulum of three-quarters of the people of Ontario.” Well-suited to the Week, her strongly defined progressive views on international copyright, women’s suffrage, and realist fiction made her work remarkable in such conservative journals as the Globe and the Post.

Duncan resigned from the Montreal Star in 1888 to circle the globe with fellow journalist Lily Lewis. She intended the trip to furnish material for a book. Both journalists described their journeys in the Star and, after the pair had arrived in London in May 1889, Duncan revised her notes, with some contributions from Lewis, and submitted the manuscript to the Lady’s Pictorial. The resulting novel, A social departure: how Orthodocia and I went around the world by ourselves, published in London by Chatto and Windus in 1890, relies on the strengths of Duncan’s journalism – close observation, description of manners, and wry humour – while transforming the narrator’s travelling companion from the sophisticated Lewis into a naive and romantic English girl. A social departure provided a pattern for Duncan’s early success as a novelist. An American girl in London (London and New York, 1891) and The simple adventures of a memsahib (London and New York, 1893) rely on the convention of a travelling outsider to create comedic clashes of manners and attitudes. Her first serious novel, A daughter of to-day (London and New York, 1894), addresses the theme of the “new woman” in the character of Elfrida Bell, an aspiring artist who champions the French Naturalists and writes a book based on her experiences as a burlesque dancer. Reviewers generally enjoyed the book, but condemned the “bad end” reserved for the heroine, who commits suicide.

A daughter of to-day was the first book to appear under the signature Duncan would use for the rest of her writing life: Mrs Everard Cotes (Sara Jeannette Duncan). She had met Cotes, a British civil servant working at the Indian Museum in Calcutta, early in 1889. He proposed, and the two were married when Duncan returned the following year. Despite plans to move to England in 1894, they remained based in India, where Cotes became a successful journalist, editor of the Indian Daily News (Calcutta) from 1894 to 1897, and later managing director of the Eastern News Agency Limited. Duncan never lived in Canada permanently again, though she would continue to visit her family and maintain her connection to Brantford by directing that the royalties on her books be paid into her bank account there. Little is known of her relationship with her husband. In the manner of other grass widows in India, she lived apart from him at times and made frequent trips “home” to England, sometimes accompanied by Cotes but often alone. Although it is tempting to speculate about their association based on her novels, it is unclear whether her strongly individualized and emotionally demanding heroines are conventions of new woman fiction or guides to her personal feelings. Certainly she maintained a harmonious relationship with Cotes, contributing articles and editorials to the papers he edited and accompanying him on working trips to Burma (Myanmar) in 1902 and Canada in 1919. Marriage did not dampen Duncan’s ambition or her output. She suggested in an interview in the Idler (London) [see Robert Barr*] that her move to India had actually facilitated her career: “One’s housekeeping is done in a quarter of an hour in the morning. . . . And there is such abundance of material in Anglo-Indian life – it is full of such picturesque incidence, such tragic chance.” She maintained a steady schedule of writing and publishing, working every morning until she had completed three or four hundred words. She continued this daily routine even when she was under treatment for tuberculosis in 1900: her autobiographical On the other side of the latch (London, 1901) was set in her garden in Simla (the summertime administrative capital of India), where she spent a year recovering. Her chronic lung problems may have been exacerbated by the extreme heat and poor sanitation of Calcutta.

A prolific and popular writer, Duncan published 22 books in all, including two volumes of personal sketches and a collection of short stories. Multi-book contracts negotiated by her literary agents in 1907, 1911, and 1922 suggest that she planned her projects far in advance of publication. Her books usually appeared in serialized versions (in periodicals such as the Times and the Queen in London and the News in Toronto) and then in book form simultaneously in Britain and the United States. She maintained connections with such important figures as George William Ross* (whom she had met in Brantford), Goldwin Smith* of the Week, John Stephen Willison of the News, novelist and editor Jean Newton McIlwraith* of Doubleday in New York, and her agents, Alexander Pollock Watt and his sons Alexander Strahan and Hansard. She played hostess to the writer Edward Morgan Forster when he visited Simla in 1912 and pursued acquaintances with the American authors William Dean Howells and Henry James, whose work she greatly admired. Forster’s letters from Simla offer a glimpse of her life in India. He found her home “quite English,” and described her as “clever and odd – nice to talk to alone, but at times the Social Manner descended like a pall.” Although her early writings suggest a lively intelligence which never suffered fools gladly, Forster’s portrait hints at a thoughtful but exclusive maturity, which perhaps only a few intimates managed to penetrate.

Despite her critical eye and sharp wit, Duncan came to identify herself with the Anglo-Indians of the Raj, possibly because they shared with Canadians a sense of marginality within the empire and similarly lacked any appreciation of their privilege in it. Her Canadian upbringing and adulthood in India made her sympathetic to the problems of representing the perspectives of the colonized. Several of her late works, including Set in authority (London and New York, 1906) and The burnt offering (London, 1909), deal with Indian nationalism. She saw colonials as more intellectually flexible, less concerned with appearance and more with principles, and more willing to see the world with “the touch of irony and of tolerance” than the British. She loved “the look of wider seas and wider skies” that travel and experiences brought to the British abroad, in contrast to the insular provincialism she deplored.

Duncan’s fiction, which illustrates the turn toward local colour realism and description of manners in late-19th-century Canadian fiction, is distinguished by her ironic tone and her interest in creating complex psychological motivation. Like Henry James, she was fundamentally concerned with point of view in fiction. Many of her novels, as their titles indicate, attempt as well to define representative types of characters, often nationally or culturally differentiated. Her work frequently focuses on females, addressing their ethical and personal choices in the context of their dual imperative to develop as individuals and to represent moral ideas. Duncan thus creates a kind of heroine who defines herself through love, travel, and artistic vocation, and whose gender politics is linked to a critique of imperial-colonial relations.

Most of Duncan’s novels are set in London or India. The notable exception is The imperialist, which depicts a by-election in small-town Elgin, a fictionalized Brantford. The hero, Lorne Murchison, runs for the Liberals on a platform of imperial federation, and his attachment to this cause is represented as a passionate young man’s belief in the ideals represented by the monarchy and the history of England. This novel, which demonstrates imperialism as a form of Canadian nationalism, also conforms to the post–Indian Mutiny representation of imperialists as self-sacrificing visionaries misunderstood by those they serve. Duncan had tried to make it her “best book,” but contemporary reaction was mixed. The London Spectator complained that it hid a medicinal message in a spoonful of jam while the Globe asserted that Duncan was disqualified by her gender from writing on political subjects. The New York Times praised the work, however, as did Toronto Saturday Night: “To the Canadian, to the Ontarian especially, it means more than any other Canadian story, for it gives with truth and with art a depiction of our own community.” Duncan wrote two other novels with significant Canadian content, Cousin Cinderella; or, a Canadian girl in London (London and New York, 1908) and His Royal Happiness (Toronto and New York, 1914), both of which represent the dominion as an approximation of the ideal community. As she had written to Archibald McKellar MacMechan* in 1905: “The Empire is a big place and interesting everywhere, but ours is by far the best part of it, and the most full of the future.”

Among modern-day critics, Carol Ann Shields [Warner*] calls The imperialist “charming and intelligent” and recommends it as a book that explains “how Canadians think.” Carole Gerson argues for Duncan’s historical importance as “Canada’s most articulate advocate of realism” and “its most accomplished practitioner.” Others find her work intriguing in its own right, and surprisingly contemporary in its subject matter and technique. Ajay Heble shows how the “de-colonisation of Canada” in The imperialist is accomplished through the skilful manipulation of narrative voice. Stephen Scobie also highlights Duncan’s technique, praising the subtle and “delicate play around what is said and not said” in her collection of novellas, The pool in the desert (New York, 1903).

During World War I, Duncan travelled between India and London, where she worked on original stage plays, which were mainly unsuccessful, and to Toronto, where a stage adaptation of His Royal Happiness appeared in January 1915. After Cotes sold the Eastern News Agency in 1919, he joined his wife in her home in Chelsea (London). Duncan came to Canada for the last time later that year with her husband, who was reporting for Reuters on the tour of the Prince of Wales. In 1921 they retired to a house in Ashtead, Surrey, where she died of chronic lung problems (possibly emphysema), exacerbated by her smoking. She was buried in the churchyard of St Giles Anglican Church, in Ashtead, with the inscription “This leaf was blown far.” She left an estate worth over $13,000. That all of it was invested in Canada indicates perhaps that she continued to regard her homeland as “full of the future.”

A bibliography of Sara Jeannette Duncan’s feature articles and uncollected stories, compiled by the author, is available at the DCB/DBC. In addition to the books listed in R. E. Watters, A checklist of Canadian literature and background materials, 1628–1960 (2nd ed., Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1972), Duncan is the author of Two girls on a barge, published in 1891 in both London and New York, written under the pseudonym V. Cecil Cotes, and Two in a flat (London, [1908?]), which appeared under the pseudonym Jane Wintergreen. A sampling of her journalism is provided in Sara Jeannette Duncan: selected journalism, ed. T. E. Tausky (Ottawa, 1978). Manuscripts of her plays are in the S. J. Duncan coll. of unpublished mss at the Univ. of Western Ont. Libraries, James Alexander and Ellen Rea Benson Special Coll., London, Ont.

AO, RG 22-322, no.5756. Dalhousie Univ. Arch. (Halifax), MS 2-82 (A. McK. MacMechan papers). NA, MG 30, D29. UCC-C, Fonds 1470, 97.094L, file 1-1. Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Wilson Library, Manuscripts Dept., 11036 (A. P. Watt and Company records). Courier (Brantford, Ont.), 7 Oct. 1907. Expositor (Brantford), 31 Oct. 1877, 13 Jan. 1891. Times (London), 24, 27 July 1922. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Misao Dean, A different point of view: Sara Jeannette Duncan (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1991). Florence Donaldson, “Mrs. Everard Cotes (Sara Jeannette Duncan),” Bookman (London), 14 (1898): 65–67. E. M. Forster, Selected letters of E. M. Forster, ed. Mary Lago and P. N. Furbank (2v., London, 1983–85). Marian Fowler, Redney: a life of Sara Jeannette Duncan (Toronto, 1983). Carole Gerson, A purer taste: the writing and reading of fiction in English in nineteenth-century Canada (Toronto, 1989). R. E. Goodwin, “The early journalism of Sara Jeannette Duncan, with a chapter of biography” (ma thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1964). Ajay Heble, “‘This little outpost of empire’: Sara Jeannette Duncan and the decolonization of Canada,” Journal of Commonwealth Lit. (London), 26 (1991), no.1: 215–28. Marjory MacMurchy, “Mrs. Everard Cotes (Sara Jeannette Duncan),” Bookman, 48 (1915): 39–40. Stephen Scobie, “The deconstruction of writing,” in his Signature event Cantext: essays (Edmonton, 1989), 25–39. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). T. E. Tausky, Sara Jeannette Duncan: novelist of empire (Port Credit [Mississauga], Ont., 1980).

Cite This Article

Misao Dean, “DUNCAN, SARA JEANNETTE (Cotes), known as Garth Grafton,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duncan_sara_jeannette_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duncan_sara_jeannette_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Misao Dean |

| Title of Article: | DUNCAN, SARA JEANNETTE (Cotes), known as Garth Grafton |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 6, 2025 |