Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WELDON, RICHARD CHAPMAN, educator, lawyer, and politician; b. 19 Jan. 1849 in Sussex Parish, N.B., son of Richard Chapman Weldon and Catherine Geldart; m. first 11 July 1877 Sarah Maria Tuttle (d. 1892) in Stellarton, N.S., and they had four sons and one daughter; m. secondly 28 Dec. 1893 Louisa Frances Hare (d. 1957) in Halifax, and they had two sons and five daughters; d. 26 Nov. 1925 in Dartmouth, N.S.

The Weldons were among the Yorkshire Methodists who settled in the Maritimes in the 18th century. Richard Chapman Weldon and his seven siblings were raised on a farm at Penobsquis, N.B., where he developed into a tall, athletic young man who loved the outdoors. Mount Allison Wesleyan College in Sackville was a natural magnet for a person with Weldon’s intellectual leanings. After graduating in 1866 with his ba at age 17, he taught school for two years near Sussex. He would later return to Mount Allison to teach and to obtain his ma in economics (1870). In 1868–69 and 1871–72 he attended Yale College in New Haven, Conn., following in the footsteps of his eldest brother. There he studied constitutional and international law under Richard Henry Dana and Theodore Dwight Woolsey, and graduated with his doctorate in political science in 1872.

Encouraged by his mentors at Yale, Weldon decided to pursue further studies in international law at the Rupert Charles University of Heidelberg in Germany. Adept at languages (he was fluent in German), he soaked up European culture, marvelling at medieval architecture and walking to nearby Mannheim to attend opera rehearsals. Perhaps the cultural diet was too rich: he suffered some kind of breakdown and had to return home in early 1873. This illness incapacitated him until 1875 when he accepted President David Allison’s offer of a professorship in mathematics and political economy at Mount Allison. The first phd to join the faculty, he quickly developed a reputation as an excellent teacher in spite of being occasionally obliged to take on subjects as diverse as botany, zoology, and geology in addition to his regular load. Weldon was a firm supporter of university consolidation in the Maritimes, serving as an examiner for the University of Halifax until its collapse in 1881.

Benjamin Russell*, a former fellow student at Mount Allison and a lifelong friend, kept Weldon abreast of the attempts to create a law school in Halifax in the 1870s and early 1880s. These centred on Dalhousie University in spite of its state of near-bankruptcy. The decision of expatriate Nova Scotian philanthropist George Munro* to endow five chairs at Dalhousie allowed these efforts to come to fruition. When Munro wrote to the board of governors in March 1883 offering $40,000 to endow a chair in constitutional and international law, he noted that Weldon had been “recommended by competent judges as most suitable to be at the head of the Law Faculty.” Weldon accepted the board’s offer, becoming the first full-time professor of law in post-confederation Canada. It may be that a “draft Weldon” movement had begun as early as 1880, when the then professor of mathematics apprenticed himself to a Sackville lawyer. Weldon’s articles were recognized by the Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society, and he was called to the bar on 9 Dec. 1884.

Modern university legal education was in its infancy in the 1880s. The Harvard law school had come out of its ante-bellum torpor only with the 1870 appointment of Dean Christopher Columbus Langdell, who clothed legal study with the mantle of a science and insisted on a more interactive and analytical classroom atmosphere. Harvard tended nevertheless to stress the instrumental and practical side of law. Weldon’s training drew him to the cultural side, and he included in the curriculum courses in international law, constitutional history, and conflict of laws. The more traditional, professionally oriented subjects were taught by his lieutenant Benjamin Russell and a group of talented members of the Halifax bar, such as Robert Sedgewick* and John Sparrow David Thompson*. Weldon managed to secure the services of John Thomas Bulmer* for a year as founding librarian, and a respectable library of some 5,000 volumes was soon in place. Weldon aired his dreams for the infant institution in his inaugural address, when he encouraged his audience “to build up in this city of Halifax a university with faculties of arts, medicine, applied science and law . . . that shall influence the intellectual life of Canada as Harvard and Yale have influenced the intellectual life of New England.”

No sooner was the law school up and running than Weldon launched into a second career as a federal mp. He ran for the Conservatives in the 1887 election in Albert, N.B., where he owned a farm. Law student Richard Bedford Bennett* helped Weldon canvass the county in the 1891 campaign, when he was re-elected. The law-school year was altered to run from September to February so as to accommodate Weldon’s absence in Ottawa. This system continued after his defeat in the Liberal sweep of 1896, when Russell in turn became an mp, and continued “through sheer academic inertia” (in the words of John Willis, the historian of the law school) until 1911, seven years after Russell’s elevation to the bench.

Weldon displayed an intense interest in public affairs and tried to instil a sense of public service in his students. By today’s standards his political career was only modestly productive, but in his own day he was a highly esteemed parliamentarian and at one point was considered as a potential prime minister. He achieved recognition mainly for an 1889 act extending existing extradition legislation to fugitives from countries with which the United Kingdom had no extradition treaty, and expanding the list of crimes for which American fugitives in Canada could be extradited to the United States. The provisions of this act, known to contemporaries as the Weldon Act, remain in today’s Extradition Act. In 1894 Weldon was responsible for the passage of a measure providing for the disenfranchisement for seven years of any person found to have sold his vote at a federal election. He himself had been accused of bribing electors in the 1887 and 1891 elections by John Thomas Hawke, editor of Moncton’s Liberal Daily Transcript, but had successfully sued for libel. Something of a gadfly to his own party, Weldon refused to support federal remedial legislation to solve the Manitoba school crisis, and urged upon a reluctant government disallowance of Nova Scotia’s 1893 legislation granting extensive rights over provincial coal to Boston industrialist Henry Melville Whitney. In early 1896 Weldon was actively involved in a clandestine attempt to find an alternative to Sir Charles Tupper* as a successor to Prime Minister Sir Mackenzie Bowell*. He ran again for parliament, unsuccessfully, in 1900 and 1906.

The law school’s success in attracting students from the west coast provided Weldon with some interesting contacts. In 1910 alumnus Richard McBride*, then premier of British Columbia, asked the dean to chair a commission charged with finding a location for the new University of British Columbia. After touring 12 communities, they settled on the Point Grey site. A less successful trip to British Columbia in 1900 had seen Weldon searching for a non-existent mica mine into which he had poured some of the family savings.

Weldon’s initial salary of $2,000 was very generous by contemporary standards (the premier of Nova Scotia earned $2,400 in 1883), but it had risen only to $3,000 by the time of his retirement three decades later. Appointed a dominion qc in 1890, he acted as counsel to the firm of Harris, Henry, and Cahan from 1897. Never wealthy, Weldon was nonetheless able to accommodate his large family in two of Dartmouth’s stately homes, Lakeside and The Brae, the latter the early Victorian mansion in which he died. The Weldons also spent some years in a gracious home on Inglis Street in Halifax’s south end.

It is a fair observation of historian Della Stanley that the school’s opening years, “which can be seen as creative and experimental, were followed by a long period of consolidation ending in routine activity and relative stagnancy.” During Weldon’s later years a new generation of students wanted more hours of instruction, and sought to have courses such as civil procedure and agency law substituted for his courses in constitutional history and international law. Their restiveness was reflected in verse in the Dalhousie Gazette in 1914, the year of Weldon’s retirement:

I’m familiar with the judgments of all the higher courts,

From the Fourteenth Century Year-Books to Dominion Law Reports;

In general jurisprudence I can give full satisfaction,

But – I don’t know what is proper for the conduct of an action.

The bar supported this move to a more professionally oriented curriculum, as did the new dean, Donald Alexander MacRae. His revised curriculum became the standard adopted by the Canadian Bar Association in 1920 and exported to emerging university law schools across the country. The liberal tradition inaugurated by Weldon was not displaced but it was somewhat overshadowed by these developments.

Weldon was the sole full-time professor at the law school during the entire 31 years of his deanship. His working relationship with his half-time colleague Russell – who called Weldon “dimidium animae meae, the other half of my soul” – has been compared to that of Langdell and James Barr Ames at Harvard and Albert Venn Dicey and William Martin Geldart at Oxford. The Weldon–Russell team covered what they believed to be the essential curriculum and relied on the Halifax bar to supply the rest. Even then, Weldon was often called upon to fill in gaps: he taught crimes for over a decade, was obliged in 1893 to take on shipping, which he then taught until 1914, and in 1905 added torts to his repertoire – all of these in addition to his “signature” courses. The efforts of Weldon and Russell to conjure up an academic legal education with virtually no resources were nothing short of heroic. If there is an aspect of Weldon’s deanship that is open to criticism, it would be the absence of women students at the law school. It is not known whether Weldon actively discouraged women from studying law, but he certainly could not have encouraged them. Nor does it seem that he urged the Nova Scotia Barristers’ Society to review its traditional exclusion of women from the profession. It was only in 1915 that the law school admitted its first woman student. Two black students graduated during Weldon’s tenure, however, the first being James Robinson Johnston* in 1898.

Given the demands on him as professor and administrator, and those of his political career, it is perhaps not surprising that Weldon left no trace in scholarship. His marked mental deterioration (probably Alzheimer’s disease), evident as early as 1906, foreclosed any possibility of academic work after his retirement. Even apart from these impediments, it may be that Weldon had no coherent vision of the Canadian constitution that he felt compelled to set down. In all that has been written about him, and in his political speeches and activities, it is difficult to discern any consistent constitutional theory on his part beyond a basic commitment to federalism and to British rather than American conceptions of law and politics. (Weldon would remain an ardent imperialist and harboured a lifelong suspicion of all things American.) In any case, during the law school’s early years the priority had to be on the educational enterprise itself, and on those foundations subsequent deans and faculty members found it easy to erect a scholarly superstructure.

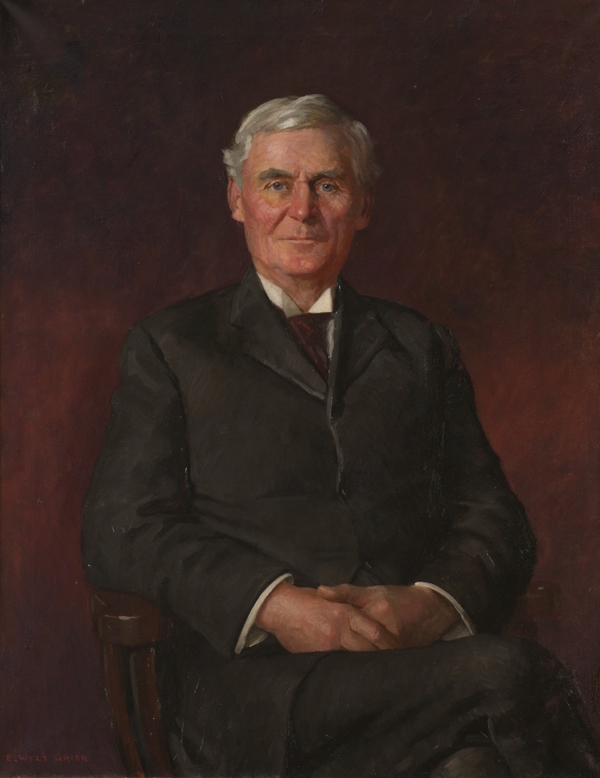

It is as an educator that Weldon is still deservedly remembered, and on this basis that historian P. B. Waite has declared that he was “of all Munro’s great gifts to Dalhousie, perhaps . . . the most fruitful one of all.” With the encouragement of the local bar, Weldon firmly anchored legal education in a university milieu, creating a model which would radiate across Canada in the 20th century. He lectured in the grand manner rather than employing the newer Socratic method of teaching, and his effect on students was magnetic. They never forgot his combination of intellectual power, impressive demeanour, and personal solicitude, which nourished a potent Weldon mystique that long outlived the dean himself. No doubt his students shared the sense of excitement that comes from being involved in any new and innovative enterprise, but it was Weldon who communicated its significance. He oriented his project around a vision of civic virtue and national service, encouraging his students to look beyond the confines of their community and even their profession. As Premier Angus Lewis Macdonald* would declare on the occasion of the school’s 50th anniversary, triumphally fêted in 1933, Weldon had given Dalhousie “not merely a Law School but a breeding ground for public service and public men.” The number of graduates who had risen to prominent positions across Canada and abroad in the judiciary, law, politics, and business by that time confirmed the accuracy of Macdonald’s eulogy. When Dalhousie opened its new law building in 1966 it was not only inevitable but appropriate that it would be named after the founding dean. On its centenary in 1983, when the law school wished to establish a new prize to honour outstanding accomplishment by a graduate, it created the Weldon Award for Unselfish Public Service. Shortly after the dean’s retirement former students had commissioned a portrait of him by Edmund Wyly Grier*. It presides in the foyer, and each new generation of students is introduced to the “Weldon tradition.”

[Weldon left little in the way of personal papers, though descendants in Halifax retain some memorabilia. The Dalhousie Univ. Arch. contains very little relating to Weldon. The Dalhousie Law School Arch. possesses not much more, but holdings include Weldon’s lecture notes from his constitutional history course and the notes of a student, Stephen Edgar March, taken in Weldon’s constitutional law course in 1891–92. His discourse at the opening of the law school was published in A. G. Archibald and R. C. Weldon, The inaugural addresses, &c. delivered at the opening of the law school in connection with Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, at the beginning of the first term in 1883 (Halifax, 1884). Aside from this item and his speeches recorded in Can., House of Commons, Debates, 1887–96, which are not extensive, Weldon left no publications, which has only added to his legend. The best treatment of his role at Dalhousie is John Willis, A history of Dalhousie law school (Toronto, 1979). Della Stanley provides as complete a biography as we are ever likely to have and examines some of the contradictions in Weldon’s life in “Richard Chapman Weldon, 1849–1925: fact, fiction and enigma,” Dalhousie Law Journal (Halifax), 12 (1989): 539–66. A sidelight on Weldon’s role as a political lobbyist aiming to obtain an exemption from anti-pollution regulations for a sawmill owner in his Albert County constituency is found in Gilbert Allardyce, “‘The vexed question of sawdust’: river pollution in nineteenth century New Brunswick,” Dalhousie Rev. (Halifax), 52 (1972): 177–90. For the Dalhousie context, see P. B. Waite, The lives of Dalhousie University (2v., Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1994–98), 1. On Weldon’s years at Mount Allison, see J. G. Reid, Mount Allison University: a history, to 1963 (2v., Toronto, 1984). Benjamin Russell’s Autobiography . . . (Halifax, 1932) contains several lengthy passages on Weldon, and includes the full text of the tribute he published in the Evening Mail (Halifax) at the time of Weldon’s retirement. p.g.]

NSARM, RG 39, ser.M, 13, file 11. Atlantic Weekly (Dartmouth, N.S.), 2 Feb. 1895. Dalhousie Gazette (Halifax), 7 Nov. 1923. Dartmouth Free Press, 22 March 1967. Evening Mail (Halifax), 27 Nov. 1925. Halifax Herald, 27–28 Nov. 1925. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 27 Nov. 1925. Alumni News (Halifax), December 1925. Can., Statutes (Ottawa), 1889: c.36; 1894: c.14. Canadian Bar Rev. (Toronto), 11 (1933): 402–3. J. E. Read, “Jurist and mentor of jurists” [book review], Canadian Bar Rev., 11: 68–69. B[enjamin] Russell, “Richard Chapman Weldon,” Canadian Bar Rev., 4 (1926): 197–200.

Cite This Article

Philip Girard, “WELDON, RICHARD CHAPMAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed June 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/weldon_richard_chapman_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/weldon_richard_chapman_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Philip Girard |

| Title of Article: | WELDON, RICHARD CHAPMAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | June 23, 2025 |