Source: Link

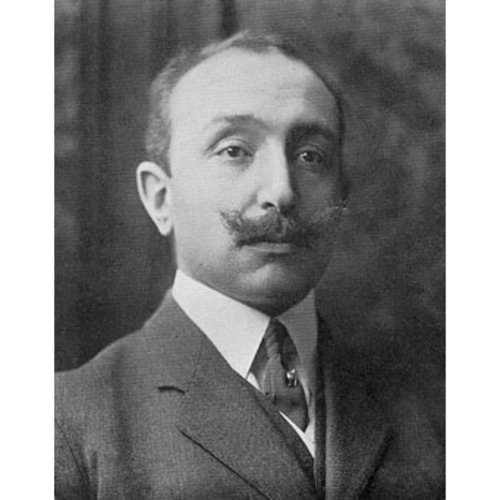

Versailles, JOSEPH (baptized Marie-Joseph-Louis de Gonzague Martin, dit Versailles), businessman and politician; b. 28 March 1881 in the parish of Notre-Dame in Montreal, son of Joseph Martin, dit Versailles, a roofer, and Julie Monarque; m. September 1904 Marie Prendergast in the parish of Saint-Jacques-le-Majeur in the same city, and they had seven sons and three daughters; d. 8 July 1931 in Montreal East and was buried two days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery, Montreal.

Joseph Versailles received his elementary schooling at the École Saint-Joseph in his native city. He spent a year at the Collège de L’Assomption, but following the accidental death of his father in 1893 he broke off his studies. He took them up again the next year at the Collège Sainte-Marie, a Jesuit institution in Montreal. Despite his mother’s straitened circumstances, the young man received a baccalauréat ès arts from the college in 1900 with the help of financial support from its authorities. That year, at the Université Laval in Montreal, he started evening courses in law, but for want of money he left in 1902 before completing them. To repay his debts and provide for his family, of which he was the eldest, he opened Versailles et Frères, a hardware store on Rue Ontario, around 1903–4.

To launch his enterprise, Versailles probably was able to take advantage of his contacts with graduates of the Collège Sainte-Marie and with some of his former teachers. All his life he would benefit from this rather extensive network not only in business but also in his activities on the nationalist scene. On 23 March 1903, at the request of Samuel Bellavance, a Jesuit priest and teacher at the Collège Sainte-Marie, Versailles and other alumni created a committee charged with establishing a vast collegial organization to seek the adoption of the Carillon–Sacré-Cœur as the national flag of French Canadians. Here Versailles drew the attention of Marie-Joseph-Alfred Prendergast, the chairman of the movement’s Montreal committee. An Irish Catholic businessman, head of the Banque d’Hochelaga, and former Zouave, Prendergast had married a French Canadian, Lucie Brault, and was active in the St Vincent de Paul Society of Montreal. In 1904 Versailles would marry his daughter Marie. Meanwhile Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* pressed Archbishop Paul Bruchési to persuade the promoters of the Carillon–Sacré-Cœur to pursue action that was more Roman Catholic than national. On 10 May 1903 Versailles proposed holding a conference that would assemble representatives of French Canadian Catholic youth educated in the classical colleges. At the Union Catholique offices in the Collège Sainte-Marie, about 100 people, responding to the invitation, met on 25 June to discuss various aspects of French Canadian society. During this event the participants laid the foundations for the Association Catholique de la Jeunesse Canadienne-Française (ACJC), which would be established on 13 March 1904. Versailles was elected president of its central committee and helped define its identity and goals.

In many respects the ACJC was a Catholic movement, and more moderate than the Ligue Nationaliste Canadienne, which was led by Olivar Asselin during the same period. According to the Association catholique de la jeunesse canadienne-française, the organization’s “goal was to bring young French Canadians together and prepare them for a life of activism for the good of religion and the homeland.” Backed by the highest levels of the Catholic clergy and inspired by Henri Bourassa*, the ACJC was meant to be an undertaking in personal development that sought to sustain religious piety among young people, but also to encourage study and action. In practical terms, it consisted of regional study circles where religious, national, and social issues were discussed. This last category encompassed education, agriculture, colonization, the working-class environment, business, and industry.

During the second conference of French Canadian Catholic youth held on 25, 26, and 27 June 1904, in which Bourassa took part, Versailles gave up the presidency because of his professional activities. On 13 Jan. 1905, when the new president, Albert Benoit, had to leave his post owing to health problems, Versailles agreed to serve as vice-president, an office he would hold until August 1909. Directly or indirectly, he would maintain ties with the association all his life. Of particular note was his participation in the 1908 conference, at which he gave a historical account of the movement. In the same year he defended the ACJC against criticism that it was merely an intellectual and moral training school and embraced too narrow a nationalism. In 1921 he would take part in the forum on industrial issues in French Canada. In a wider context the ACJC was one of the movements that in the 1910s gave rise to the Ligue des Droits du Français, renamed the Ligue d’Action Française in 1921. Versailles was involved in this association, which took up the torch of French Canadian nationalism, notably through articles he wrote for L’Action française at the beginning of the 1920s. Shortly before his death he sought to persuade the ACJC to buy the Palestre Nationale of the Association Athlétique d’Amateurs Nationale [see Raoul Dumouchel], whose continued existence was threatened by the Great Depression.

Versailles also attracted attention as a businessman and politician. In 1908 he sold his hardware store to go into property development with, among others, his brother Jean and his father-in-law. To take advantage of Montreal’s eastward expansion, they set about buying a 1,400-acre lot northeast of Maisonneuve (Montreal). In 1909 they subdivided one part of it to build some 30 houses that they resold. To profit further from the growth in this district, they requested, and on 4 June 1910 obtained, the incorporation under the name Montreal East of a piece of land bounded by the Rivière des Prairies to the north, Montreal to the west, Pointe-aux-Trembles (Montreal) to the east, and the St Lawrence River to the south. Versailles became its first mayor and, repeatedly re-elected by acclamation, was to remain in the post for the rest of his life.

Several sources suggest that Versailles and his partners, some of whom formed the first municipal council, harboured the ambition of making this new town a garden city. Their concept reflected the model developed late in the 19th century by the English town planner Ebenezer Howard as a reaction to large industrial cities; it was characterized by low population density and a high degree of planning. Numerous property-development projects were initiated in Quebec at the time, but they did not progress beyond vague statements of intent. Some critics accused Versailles of seeking to emulate promoters who were content to secure the rapid growth of their town at the cost of excessive indebtedness that made annexation to Montreal inevitable. On the 15th anniversary of Montreal East, Versailles would counter that the municipality had been planned so that it would encourage and benefit from the development of the eastern end of the island of Montreal, which the former mayor of Montreal, Raymond Préfontaine*, was fervently supporting.

As mayor, Versailles oversaw the installation and improvement of the infrastructure and services of his town: water-distribution systems, drains, electric lighting, telephones, railways, streetcars, and port facilities. The municipal council made some effort to beautify the town by, for example, planting several thousand trees along the streets and financing the laying-out of the first park. The growth of Montreal East, nevertheless, remained slow and difficult in an economic climate that was less and less favourable. To complicate matters World War I came along. Materials and labour were channelled into war industries, which put a stop to residential construction. In 1915, however, the Queen City Oil Company Limited, the forerunner of the Imperial Oil Company, established itself in Montreal East, giving the town its second wind. Whatever the original intentions of its founders, Montreal East continued on this new course of promoting business. Versailles went to New England to vaunt the attractions of his industrial suburb, which would welcome additional enterprises throughout the war and even afterwards. The municipal council struck a select committee to solicit and study such projects and increased the number of measures designed to encourage the setting-up of new industries, paying special attention to fiscal and town-planning matters. Moreover, unlike other working-class and industrial suburbs of the island of Montreal, notably Maisonneuve [see Oscar Dufresne], Montreal East retained its autonomy.

In 1919, at the invitation of Télesphore-Damien Bouchard*, the mayor of Saint-Hyacinthe, and along with his counterparts from Outremont (Montreal) and Pointe-aux-Trembles, Versailles took part in founding the Union of Municipalities of the Province of Quebec. As mayor, he participated in a bitter fight against the Canada Cement Company Limited. Established in Montreal East, the company, which had a virtual monopoly on cement in Canada, refused to pay municipal taxes. Versailles started legal proceedings and in 1921 obtained compensation at the end of a lengthy trial that led the litigants all the way to the Privy Council in London. The confrontation continued outside the judicial arena. Indeed, in 1925 Versailles founded the Compagnie de Ciment Nationale to compete with Canada Cement. The enterprise was only modestly successful because Versailles used it mainly to wage a price war. When the English Canadian businessman Sir Herbert Samuel Holt* and his partners acquired Canada Cement in 1927 and drove out the mayor’s opponents from its management, Versailles agreed to let them have the Compagnie de Ciment Nationale.

In 1913 Versailles had founded a brokerage business, Versailles, Vidricaire, Boulais, Limited, to facilitate the financing of the public works required for the development of his suburb. His partners were Emmanuel-Cléophas Vidricaire, the former assistant manager of the head office of the Banque d’Hochelaga and a teacher at the École des Hautes Études Commerciales de Montréal, and Joseph-Félix-Frédéric Boulais, a notary and manager of various branches of the Banque d’Hochelaga. Initially the company specialized in selling bonds issued by municipalities and school boards. During the course of World War I it took part in the sale of Victory Bonds and, armed with this experience, diversified its activities considerably. The firm opened offices in Quebec City and Ottawa, and then in Boston, and did business with a myriad of companies, including the Montreal Tramways and Power Company; Dupuis Frères, Limitée; and Regent Knitting Mills Limited. It also helped finance enterprises on whose boards of directors Versailles sat, such as J. B. Baillargeon Express Limited, the Fabriques de Pâtes et de Papier du Québec, Caron Brothers Incorporated, and the Brasserie Frontenac, or which he managed, such as the Compagnie de Ciment Nationale. Versailles, Vidricaire, Boulais, Limited also underwrote the bond issues of a number of municipalities, religious congregations, and parishes. In partnership with other firms, it sold provincial bonds. It would remain in business until 1943.

Besides owning the brokerage company, Versailles was active outside the world of commerce. In 1913 he also left his mark on the urban environment with the construction of the Versailles Building. The ten-storey edifice, on Rue Saint-Jacques in Montreal, housed the firm’s offices as well as those of the ACJC and numerous French Canadian notaries and lawyers. Through his company, he helped fund such Montreal institutions as the Université de Montréal and the Conservatoire National de Musique et d’Élocution. From 1919 to 1927 the firm published and circulated La Rente: guide de l’épargne et du placement. This twice-monthly review promoted economic development among French Canadians. In a series of scathing articles, for example, it attacked the clichés that would impede their progress in this area (such as “Nous sommes jeunes” [We are young] and “Nous sommes pauvres” [We are poor] in its 1 Sept. 1920 issue). La Rente also favoured the businesses in which Versailles and his partners had an interest. On 1 July 1924 Versailles notably used it to justify setting up the Compagnie de Ciment Nationale. The periodical was managed by Olivar Asselin, whom Versailles recruited shortly after his demobilization, not only as editor but also as secretary. Their collaboration lasted only a short time. The exact nature of their disagreement is unknown, but it can easily be surmised that the two men were not destined to get along. Asselin’s rebellious nationalism was in stark contrast to the more level-headed nationalism of Versailles.

Joseph Versailles cannot be considered an important thinker on French Canadian nationalism with regard to either his influence or the number of his writings even during his association with the ACJC. But in his actions and in his few articles, he embodied a certain kind of French Canadian economic nationalism. A successor in this regard to Robert-Errol Bouchette* or Étienne Parent*, he believed that the salvation of French Canadian nationality lay in its full participation in industrial capitalism. In his opinion, the role of a businessman was to contribute to such participation by enabling his compatriots to master the necessary tools and knowledge. For example, a businessman could guide small investors towards the most profitable ventures within and beyond the province of Quebec. A herald in his own way of the Quiet Revolution, Versailles proposed instruments of leverage with which French Canadians would be able to emerge from their economic inferiority (he would never go so far as to suggest that the state was one of those instruments). Pierre Elliott Trudeau*, in a chapter of La Grève de l’amiante published in Montreal in 1956 (translated by James Boake and brought out in 1974 as The asbestos strike), would quote Versailles to illustrate a type of French Canadian thinking about the economy. In his opinion, its proponents would always be incapable of extricating themselves from the nationalist rut, an inability that would keep them from analysing and facing the economic state of affairs in society. Yet Versailles, a product of the classical colleges, had turned his back on the liberal professions to go into business. Subscribing to French Canadian nationalism, but without involving himself in the debates that were to pit Henri Bourassa against Lionel Groulx*, for example, he was far from doctrinaire. He was nevertheless convinced that, to take their rightful place in North America, French Canadians could and should invest their capital intelligently. According to an article published in La Quinzaine musicale, “Versailles proved that Canadian finance, Canadian capital are part of our historical narrative.”

Joseph Versailles is the author of, among other works, the following: “Dévions-nous?,” Le Semeur (Montréal), 4 (1907–8): 309–16; “Comment servir: l’homme d’affaires,” L’Action française (Montréal), 4 (1920): 483–91; and “La jeunesse et les carrières économiques,” L’Action française, 7 (1922): 31–42. The marriage certificate can be found in an incomplete register.

FD, Notre-Dame (Montréal), 29 mars 1881; Saint-Jacques, cathédrale de Montréal [Saint-Jacques-le-Majeur], septembre 1904. Le Devoir, 1922–31. La Patrie, 1904–31. Le Progrès de Valleyfield (Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, Québec), 10 avril 1903. Olivar Asselin, “Le trust des ciments et la Cie de ciment nationale,” La Rente: guide de l’épargne et du placement (Montréal), 1er juill. 1924: 4–8. Assoc. Catholique de la Jeunesse Canadienne-Française, Association catholique de la jeunesse canadienne-française (Montréal, 1904); Le Congrès de la jeunesse à Québec en 1908 (Montréal, 1909); Le problème industriel au Canada français: rapport officiel du Congrès industriel tenu par l’A.C.J.C. à Québec, les 1er, 2 et 3 juillet 1921 … (Montréal, 1922). S[amuel] Bellavance, “Historique de notre association,” Le Semeur, 6 (1909–10): 86–92, 109–15; Pour préparer l’avenir (Montréal, 1914). [Ovila Fournier], Un pionnier de l’économique au Québec: Joseph Versailles (1881–1931), le fondateur de Montréal-Est (Saint-Étienne-de-Bolton, Québec, 1974). J.‑E. Lapierre, “Feu Joseph Versailles,” La Quinzaine musicale ([Montréal]), 1 (1930–31): 149. Que., National Assembly, “Journal des débats”: www.assnat.qc.ca/en/travaux-parlementaires/journaux-debats.html (consulted 9 Sept. 2014). Laurier Renaud, La fondation de l’A.C.J.C.: l’histoire d’une jeunesse nationaliste (Jonquière [Saguenay, Québec], 1972). Isidore Robert et Jean Nil, “Compte rendu du congrès de 1904,” Le Semeur, 1 (1904–5): 3–54. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec; Hist. de Montréal. Ville de Montréal, “Old Montréal”: www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca (consulted 6 April 2010).

Cite This Article

Harold Bérubé, “VERSAILLES, JOSEPH (baptized Marie-Joseph-Louis de Gonzague Martin, dit Versailles),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 3, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/versailles_joseph_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/versailles_joseph_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Harold Bérubé |

| Title of Article: | VERSAILLES, JOSEPH (baptized Marie-Joseph-Louis de Gonzague Martin, dit Versailles) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2017 |

| Year of revision: | 2017 |

| Access Date: | March 3, 2026 |