Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

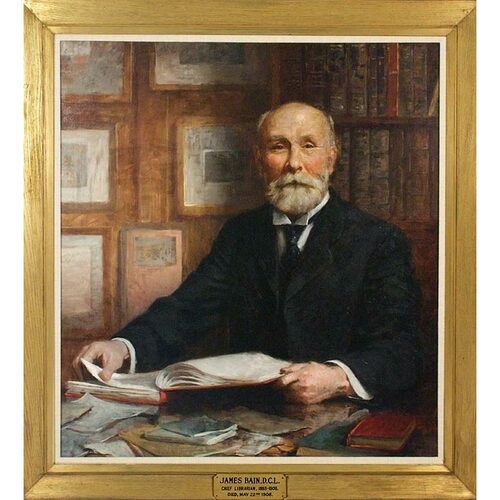

BAIN, JAMES, bookseller, publisher, and librarian; b. 2 Aug. 1842 in London, England, eldest son of James Bain, a bookseller, and Joanna Watson; m. 1 Jan. 1875 Jessie Mary Paterson, his second cousin, in Edinburgh, and they had four children, one son surviving childhood; d. 22 May 1908 in Toronto.

James Bain’s parents returned to their native Edinburgh in 1844, and two years later his father was appointed head of Hugh Scobie*’s book and stationery shop in Toronto on the recommendation of William Darling*, a Montreal merchant originally from Edinburgh. In May 1846 the Bain family arrived in Toronto, where James attended the Toronto Grammar School. When his father opened his own bookshop in 1856, Bain dropped out of school to help; his formal education thus ended when he was 14.

In 1866 Bain entered the employ of James Campbell and Son, Toronto publishers and wholesale booksellers, as a travelling salesman in Upper Canada, the Maritimes, and the United States. He made his first annual buying trip to Britain in 1870, and in 1875 became head of the company’s new agency in London. Resigning from James Campbell and Son in 1878, he entered into a partnership with a London publisher to form J. C. Nimmo and Bain. Although the firm published a number of books its profits were not enough to support two families, and in 1881 he accepted an offer from James Campbell’s son, William Cooper Campbell, to manage his new Toronto firm, the Canada Publishing Company, at a salary of $1,500.

Bain returned to Toronto with his family on 31 Dec. 1881, at a time when Alderman John Hallam was leading a movement for a free public library. After enabling provincial legislation was passed in 1882, a by-law establishing a public library was approved in a plebiscite on 1 Jan. 1883. Hallam chaired the library board, and at its inaugural meeting he described what he thought the library – and the chief librarian – should be. The library should contain standard books on all subjects and a careful selection of light reading, avoiding “the garbage of the modern press.” The main concern, however, should be the development of a major all-inclusive collection of Canadiana. The chief librarian should be a scholar “minutely familiar” with Canadian history and literature. The salary had been set at $2,000.

The board considered four candidates for the post of chief librarian, John Charles Dent*, Graeme Mercer Adam*, John Thomas Bulmer, and Bain. Dent was the favourite, but it was Bain who was finally elected by a five to four majority. Dent’s supporters were furious; one board member resigned, and a vituperative attack was launched in the newspapers against Bain as a “fourth rate commercial traveller.” Meanwhile Bain assumed his new position. The Toronto Mechanics’ Institute had been dissolved, and its property transferred to the library. Bain chose about 8,500 books from its collection, and with the advice of experts selected and bought another 23,000 volumes. On 6 March 1884 the Toronto Public Library opened in the renovated mechanics’ institute building.

Throughout his career at the library, Bain struggled with inadequate funding in an inadequate building. After the initial expenditure, the annual book budget averaged about $6,000. Books were cheap, but it was still difficult to provide enough for the central library and two branches serving a rapidly growing city as well as build a Canadiana collection, and for 25 years Bain practised strict economy. The library board had to sue the city council for operating funds in 1900; it was obvious that money was not going to be available for a new library to replace the outgrown building. In 1903 Bain successfully sought a grant of $350,000 from Andrew Carnegie for a new central library and three branches. Labour groups objected because of Carnegie’s reputation as an employer, but the gift was accepted by city council. Bain worked hard planning the new buildings and coping with controversies over the site and architects of the central library, as well as placating a somewhat irascible donor. Only two branches were completed before his death; when the central library opened in 1909 it was regarded as Bain’s memorial.

Bain also worked hard building the book collection. It was always stronger in the humanities than in the sciences, and also had a strong British slant, like Toronto itself. Fiction had been controversial from the beginning: Goldwin Smith and others had opposed the establishment of the library because taxes would be used to circulate novels. Apparently successful in avoiding problems, Bain was praised for his “tactful and courageous selection” of fiction. He was always more interested, however, in acquiring books for serious study; his greatest enthusiasm was for the rare Canadian collection.

It was not until 1887 that the board officially adopted Hallam’s proposal to acquire “every work of any consequence” bearing on Canadian history and literature. Because books were published by small presses across Canada, much effort was needed to locate current titles; even more effort was required to find out-of-print or early rare works. Bain aggressively pursued the new and the old, rapidly building a significant collection. When the reference library’s catalogue was published in 1889, its Canadian section was much admired, especially the rare books. Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau* thought the number of current French Canadian titles was “wonderful” and offered to help Bain find Quebec publications. By 1907 Bain wrote of his difficulty in adding to the rare Canadian collection because it was so large. It is now in the Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library, along with Bain’s personal collection of rare Canadian books and pamphlets.

Besides selecting all the books, Bain provided most of the library’s assistance to readers, both in person and by correspondence. His voracious reading and retentive memory gave him a knowledge of history, literature, and bibliography that was both extensive and precise; he also possessed “perfect patience with illiteracy,” so that he could give courteous, kindly, expert help to everyone. He was especially helpful to authors – he recommended sources, read their manuscripts, introduced them to publishers, and arranged newspaper notices and favourable reviews. Almost more important than his practical help, however, was the warm encouragement he gave them.

Bain belonged to many organizations, often holding office or sitting on important committees. He was a founder of the Canadian Society of Authors in 1899, the Ontario Library Association in 1900 (he served as president in 1901–2), and the Champlain Society in 1905. He was president of the Canadian Institute in 1900–2 and the St Andrew’s Society of Toronto in 1905–7. At Douglas Brymner’s request, Bain followed him from 1897 to 1900 as Canadian representative on the Historical Manuscripts Commission of the American Historical Association. A staunch Presbyterian, he was convener of the General Assembly’s committee on sabbath-school publications from 1903 to 1908 and a member of the senate of Knox College, Toronto. Probably the society that gave him the greatest pleasure was the Muskoka Club, a small informal group of pioneer vacationers to Muskoka; in 1860 Bain had been one of the earliest tourists in the region.

In 1902 Bain was granted an honorary dcl by Trinity University, Toronto, for “distinguished service in the cause of education”; in 1908 William Glenholme Falconbridge* called his death from cancer an “irreparable public calamity.” Bain had laid solid foundations for the Toronto Public Library, and built a Canadian collection that has served generations of scholars and students. He was one of the first public librarians in Canada – he was also one of the best.

James Bain prepared a new edition of Travels & adventures in Canada and the Indian territories between the years 1760 and 1776 by Alexander Henry* the elder (Toronto, 1901; repr. Edmonton, 1969); it is available as well in a 1901 Boston edition and in several modern American reprints. Bain’s publications also include many articles and books reviews on libraries and Canadian history; listings of these works are available in CIHM Reg., in Canadiana, 1867–1900, and in Stephanie Hutcheson, “Towards a bio-bibliography of James Bain, first chief librarian of the Toronto Public Library” (paper prepared for mls program, Univ. of Toronto, 1973).

Sources for Bain’s role in the early history of the Toronto Public Library are found in the MTRL, including the Toronto Public Library papers, the pamphlet Testimonials to accompany the application of Mr. James Bain, Jr., for the position of chief librarian to the Toronto Free Library (Toronto, 1883), and the Toronto Public Library’s publications from 1883 to 1909, notably its Annual report, 1883/84–1909, and the catalogues of its collections. Bain’s papers in the possession of his descendants are also important.

The following Toronto newspapers were consulted for specific periods between 1883 and 1908, supplementing newspaper clippings in the Bain papers and in the MTRL’s scrapbooks on the Toronto Public Library (preserved on mfm.): the Evening News (to 1903, continued as the News); the Evening Star (1892–1900, continued as the Toronto Daily Star); the Evening Telegram; the Globe; the Toronto Daily Mail (to 1895) and its successor the Daily Mail and Empire; and the World.

MTRL, E. S. Caswell, “The Toronto Public Library: a historical sketch of its first quarter-century” (typescript, [193-?]). Univ. of Toronto Library, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, ms Coll. 106 (William Kingsford papers). Margaret Beckman et al., The best gift: a record of the Carnegie libraries in Ontario (Toronto, 1984), 96–101. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). T. E. Champion, “A great librarian: the late James Bain, d.c.l.,” Canadian Magazine, 31 (May–October 1908): 223–26. A. H. U. Colquhoun, “Canadian celebrities, no.XIII – Mr. James Bain, Jr.,” Canadian Magazine, 15 (May–October 1900): 31–33. Dict. of Toronto printers (Hulse). W. J. Loudon, Studies of student life (8v., [Toronto], 1923–[4-?]), 8: 13–24. Susan McGrath, “The origins of the Canadiana collection at the Metropolitan Toronto Central Library: the first twenty-five years,” BSC Papers, 13 (1974): 85–100. D. H. C. Mason, Muskoka: the first islanders (Bracebridge, Ont., 1957). Muskoka and Haliburton, 1615–1875; a collection of documents, ed. F. B. Murray (Toronto, 1963). Ontario Library Assoc., The Ontario Library Association, an historical sketch, 1900–1925 (Toronto, 1926). Margaret Penman, A century of service: Toronto Public Library, 1883–1983 (Toronto, 1983). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.2.

Cite This Article

Edith G. Firth, “BAIN, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bain_james_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bain_james_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Edith G. Firth |

| Title of Article: | BAIN, JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 17, 2025 |