Source: Link

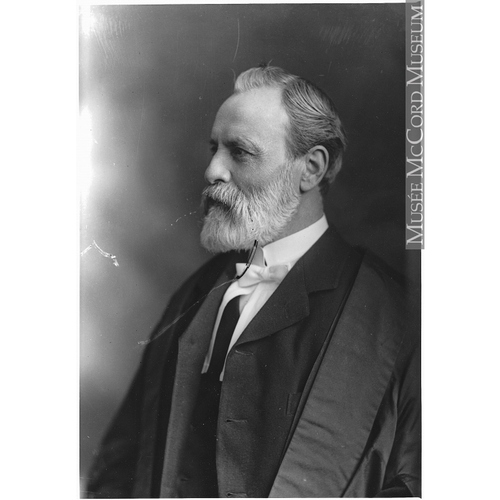

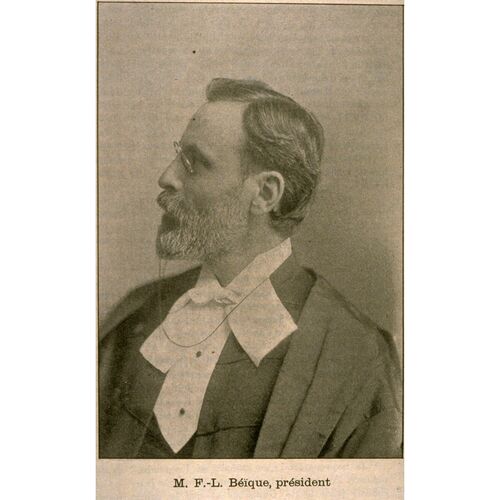

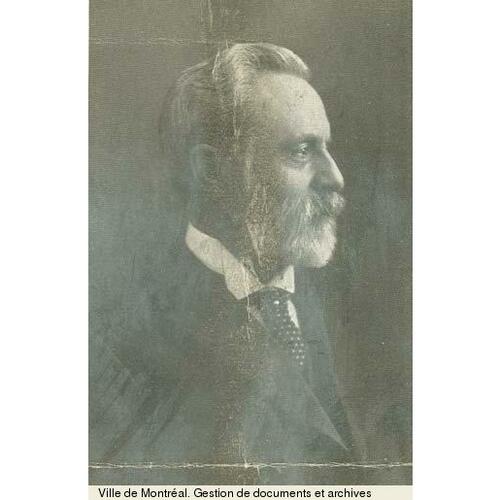

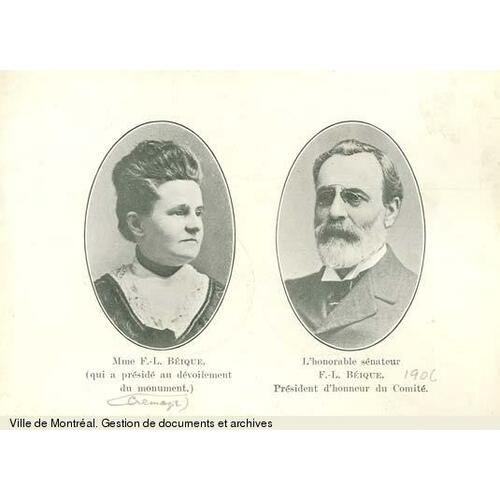

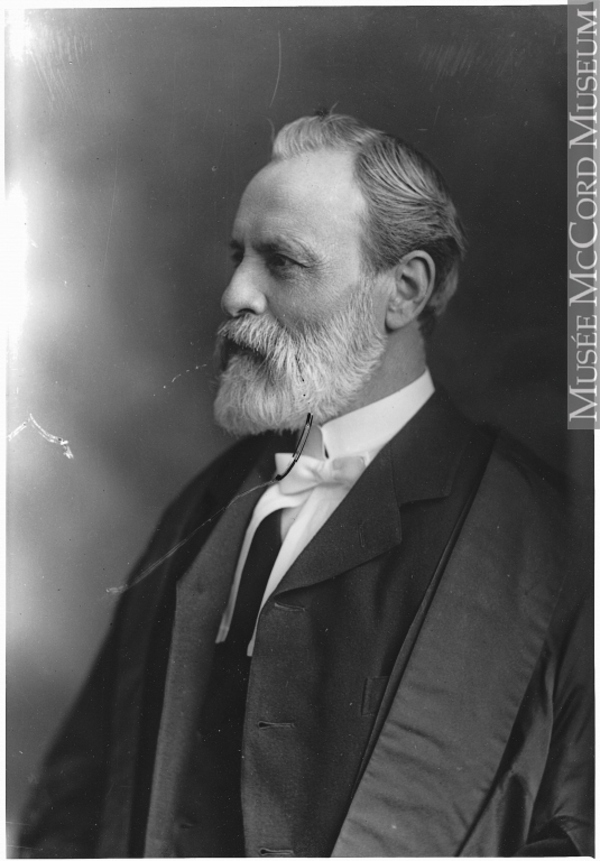

BÉÏQUE, FRÉDÉRIC-LIGORI (baptized Frédéric-Liguory Beic), lawyer, businessman, and politician; b. 20 May 1845 at Saint-Mathias-de-Chambly (Saint-Mathias-sur-Richelieu), Que., son of Louis Béïque (Beic), a farmer, and Elizabeth L’Homme; m. 15 April 1875 Caroline Dessaulles*, only daughter of Louis-Antoine Dessaulles* and Catherine-Zéphirine Thompson, in the parish of Saint-Jacques, Montreal, and they had ten children; d. 12 Sept. 1933 at LaSalle (Montreal).

Education and legal career

The son of an illiterate farmer, Frédéric-Ligori Béïque was the ninth of ten children born on a farm in Saint-Mathias-de-Chambly. His education began in the parish’s small school. At the age of ten he continued his studies at the Collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir in Marieville and then paused them for a few years. When he reached the age of 14, his father placed him in an anglophone family to learn English; he remained with them for seven months. It seems that his brother Louis-Trefflé, a lawyer, steered him towards his own profession and persuaded him to return to the Collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir to continue his classical studies at an accelerated pace and finish them with philosophy in Montreal. Béïque attended François-Maximilien Bibaud*’s law school and articled with various renowned Montreal law offices, most notably that of Cyrille and François-Xavier Archambault. He was admitted to the Quebec bar in 1868 and wanted to go into practice with Louis-Trefflé, but the latter dissuaded him, with the result that he took his first modest steps on his own. Subsequently, in 1871 and 1872, he worked with Joseph-Emery Robidoux, two years his senior, in the practice of Robidoux et Béïque. Around 1873 he went into partnership with Louis-Amable Jetté*. After Jetté was appointed a judge of the Superior Court of Quebec for the district of Montreal in 1878, undertaking a parallel career as a professor of law, Béïque became the principal lawyer of the firm, now known as Béïque et Choquet [see François-Xavier Choquet*]. He took on law graduates and young lawyers as associates until 1902 and then began to integrate his sons Louis-Joseph, Henri-Alphonse, and Frédéric-Auguste into the practice. Increasingly, they took over throughout the 1910s, although Henri-Alphonse entered into separate partnerships with other associates on a number of occasions. Appointed a qc by the Quebec government in 1879 and by the Canadian government ten years later, Béïque had been bâtonnier of the Montreal bar from 1890 to 1892. In 1900 he was awarded an honorary lld by the Université Laval in Quebec City.

In his legal career Béïque stood out more for his competence and rigour than for his qualities as an orator; he was hampered by a stutter, but he often knew how to turn it to his advantage. In particular, he brought his expertise to the inquiry into the John Patrick Whelan affair [see Ernest Pacaud*] in 1890, to the royal commission of inquiry into the Baie des Chaleurs Railway matter [see Pacaud] as counsel to Quebec’s premier Honoré Mercier* in 1891, and to the Behring Sea Claims Commission [see Alexander MacLean*] as Great Britain’s associate legal counsel in 1896–97. His talents also enabled him to play an important part in creating several major enterprises in the fields of electricity and urban transportation, including the Royal Electric Company, which merged with the Montreal Light, Heat and Power Company [see Sir Rodolphe Forget*]; the Montreal Park and Island Railway Company, which was absorbed by the Montreal Tramways Company in 1911; and the Chambly Manufacturing Company. As well, he was involved in the textile industry (Canadian Cottons Limited, for example). Béïque invested in many of these companies, and he was elected to sit on their boards of directors; he also held managerial positions in some cases. He was even appointed to the board of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, a rare privilege for a French Canadian.

Founding the Parti National

In 1871, at the beginning of his legal career, Béïque had tried his hand at politics with a group of lawyers who were very committed to a French Canadian nationalist approach, in particular Jetté. Béïque and Jetté were central to creating the Parti National and formulating a political program aimed at bringing together Liberals – including Antoine-Aimé Dorion*, Joseph Doutre*, Wilfrid Laurier*, Honoré Mercier, and Félix-Gabriel Marchand* – and Conservatives such as Louis-Onésime Loranger*. The movement met with some success in the federal election of 1872: with the help of Béïque as chief organizer, Jetté convincingly defeated Sir George-Étienne Cartier* in Montreal East. Although Béïque was not a candidate, he formed very close political and personal ties, especially with Laurier, which were to prove useful. He was not on the front lines of electoral contests but acted more as a political and legislative adviser.

Speculating in property

In July 1873, as a young lawyer, Béïque joined with Jetté and seven other partners in speculative real-estate projects in the village of Hochelaga (Montreal). The group included two other lawyers (Jean-Baptiste Lafleur and Francis Alphonse Quinn), three merchants (grocers Charles Desmarteau and Charles Lamoureux, and footwear retailer Edmond Saint-James, dit Beauvais), and two factory owners (Joseph-William Crevier and Joseph Dinham Molson). For $110,000 they purchased several lots to be subdivided, which required multiple commercial transactions until the beginning of the 1880s. In 1875 Béïque’s share in the land holdings allowed him to provide the $10,000 specified in his marriage contract with Caroline Dessaulles. In April–May 1874, five of the nine partners – Jetté, Béïque, Lafleur, Quinn, and Desmarteau – had joined another group of speculators that included such prominent Liberal politicians as Marchand, Toussaint-Antoine-Rodolphe Laflamme*, and Wilfrid Prévost, as well as numerous merchants and building contractors from Montreal and the surrounding area. The 15 associates chose two vast properties near the Lachine Canal, which offered possibilities for development. They acquired the first block for $140,000 and the second for $100,000, paying 15 per cent in cash and spreading the rest of the payments over several years, a common practice in this type of venture. The investors could thus wait for the plots to increase in value and, if development went according to plan, make a good profit. The federal government accused them of having taken advantage of inside political information on the plan for widening the canal [see Jetté]. The first block was sold to Victor Hudon*, a Montreal merchant, for $163,500 in October 1874, and the second that same year to the Sisters of Charity of the Hôpital Général of Montreal, among several other sales. The net results of the enterprise were capital gains and periodic income from purchasers. It seems that after the early 1880s Béïque did not repeat his large-scale speculative experiments except for his acquisition, in 1909, of two enormous farms in the area of Saints-Anges-de-Lachine (Montreal), one to use as a vacation destination and the other for long-term speculation.

The Senate

The further Béïque advanced in his legal career, the more frequently he attained positions of strategic importance. In 1902 his political connections in Liberal circles led to his becoming, on Laurier’s recommendation to Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*], senator for the Salaberry division. The prime minister could count on him for an informed opinion on difficult political and legislative issues, and occasionally on cases concerning patronage. Béïque was especially interested in railway, financial, commercial, and industrial affairs, as well as in relations with Quebec’s Liberal government and Liberal newspapers [see Godfroy Langlois*]. It was clear that Laurier respected and gave much weight to the senator’s opinions and could speak frankly with him on the political issues of the day. These close links explain why Béïque and Louis-Philippe Brodeur*, judge of the Supreme Court of Canada, acted as executors for Laurier in 1919 and, together with Senator Joseph-Marcellin Wilson, for Lady Laurier in 1921.

For more than 30 years Béïque’s talents and experience were evident in the Senate, where he quickly assumed a leadership role, especially in matters connected with his predominant interests. The Debates are filled with his forceful, constructive speeches, which advanced the legislative process and whose value was recognized by his peers. They reveal his explicit opinions on national issues, principally in July 1905 on the question of separate schools in the new provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan [see Laurier; Sir Clifford Sifton*; Settlement of the West] and in March 1912 on the extension of Manitoba’s territory [see Sir Rodmond Palen Roblin]. Consistent with the French Canadian nationalist perspective of the time, Béïque based his interpretation on the text of the 1867 Canadian constitution, which in his view upheld, by extension, the obligation to establish and maintain separate schools in these provinces. More generally, he supported the theory of two founding nations, Roman Catholic and Protestant, whose constitution protected equal rights for minorities in every province.

Béïque also believed that the country would benefit from the preservation of distinct English- and French-language groups, working together as much as possible and contributing their respective qualities to Canada’s well-being. In March 1915 he returned in greater depth to the question of the use of the French language during the debates on bilingual schools in Ontario occasioned by Regulation 17 [see Sir James Pliny Whitney*]. Even though he stressed that the Canadian constitution guaranteed the use of French in federal institutions, he turned to a political argument to encourage English Canadians not to favour an assimilative approach: it would not be in their best interest to incite strong opposition from a community whose survival is threatened. On these occasions Béïque’s nationalism was expressed in political speeches and, more substantively, in his ongoing promotion of French Canadian economic and financial advancement in Quebec.

Managing various companies

In 1910 Béïque was elected to the board of directors of the Banque d’Hochelaga, one of three French Canadian banks, and in 1912 to the vice-presidency, succeeding Janvier-Arthur Vaillancourt, who had became president. Unsurprisingly, Béïque may have played a role in hiring Beaudry Leman – his son-in-law since 1908 and a practising engineer involved in producing and distributing electricity in Shawinigan Falls (Shawinigan) and Montreal – as agency manager at the Banque d’Hochelaga in 1912 and as general manager in 1914. Vaillancourt, Béïque, and Leman were central to negotiations with the provincial government [see Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*] for the 1924 absorption by the Banque d’Hochelaga of the Banque Nationale, which had been experiencing difficulties for several years, to form the Banque Canadienne Nationale in 1925. Béïque shared the vice-presidency of the new institution with Georges-Élie Amyot*, former president of the Banque Nationale, until 1928; he subsequently became president and held that position until his death in 1933. During his last years Béïque was pictured with his son-in-law on the front of the bank’s paper currency, which was highly unusual. In this way he demonstrated the importance he attached to creating and sustaining financial institutions for his compatriots, an objective also evident in his management, with Leman, of General Trust of Canada from its establishment in 1928 until 1933.

Béïque also left his mark on many Montreal institutions. At the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal, he acted in several capacities: as a director, as a corporate lawyer (who seldom charged for his services), as a moving spirit behind the construction of the Monument National (from 1891) and the Caisse Nationale d’Économie (a pension fund founded in 1899), and as president (1899–1905). For almost a decade, until 1929, he was also president of the governing council of the Université de Montréal, where he was active in drafting its charter and constructing a university hospital and the main building, both designed by the architect Ernest Cormier*. The government of France made him a chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur in 1925.

Family and succession

In 1892 Béïque had taken up residence on Rue Sherbrooke, in the midst of Montreal’s financial and professional elite, on a property acquired by his wife at the end of 1890 as a shelter from the vagaries of business. The family grew, numbering a total of ten, one of whom, Georges-Edgar, died in childhood. Of the couple’s sons, four became lawyers (Louis-Joseph, Henri-Alphonse, Frédéric-Auguste, and Victor-Édouard) and the other three civil engineers (Paul-Albert, Eugène-Rodolphe, and Jean). Daughter Caroline married Leman, and her sister, Alice, married the engineer and trader Pierre Charton. Caroline Dessaulles, like many women married to members of Montreal’s professional and business elite, immersed herself in numerous social and charitable causes, especially in organizing schools of household science [see Jeanne Anctil*], where she played a decisive role.

As he neared his 80th birthday, Béïque was in possession of a large fortune in property and shares, the disposition of which he had to arrange in order to pass them on to the next generations – his children, of whom the oldest were in their forties, and their offspring. To this end, in 1924 three of his sons incorporated the company Lasalle Inc. to manage these assets as well as those of their mother. In October their parents transferred the assets to the company in exchange for shares and then recovered them at the end of December through a legal mechanism known as retrocession. Not only did this provision allow the aging couple’s assets, especially their real estate, to be managed, but it also made the various holdings accessible to family members and avoided inheritance taxes. Furthermore, in 1929 their son Jean’s marriage contract included the transfer of most of these assets, with the exception of those accruing to Béïque as a senator and company director, to a trust formed by the couple’s sons and sons-in-law. The marriage contract became a kind of will, with the assets being shared among the children and large settlements for some of them. Finally, a few months before Béïque’s death in 1933, he and his wife transferred the management of all assets to General Trust of Canada, including those of Lasalle Inc., whose charter was surrendered that year. Another company, F. L. Béique Inc., created by three of the sons in 1931, already held some of the assets.

From the end of 1927, Frédéric-Ligori Béïque and his wife rented out their house on Rue Sherbrooke through Lasalle Inc. They joined several of their children on their properties in Lasalle (known as Saints-Anges-de-Lachine before 1912), where they gradually settled in for holidays or permanently. After suffering cardiac arrest, Béïque died on 12 Sept. 1933 at the age of 88. He was buried two days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery in Montreal following a very large funeral at the basilica of Notre-Dame. His unceasing and varied activities had produced remarkable results, particularly through their impact on federal politics during Laurier’s administration and on the increased presence of francophones in Quebec’s business and financial spheres.

BANQ-CAM, CE601-S33, 15 avril 1875; CE602-S22, 22 mai 1845; CN601-S311, 11 avril 1875. FD, Notre-Dame (Montréal), 14 sept. 1933. LAC, R7648-0-6; R10811-0-X. McCord Museum (Montreal), P010 (Dessaulles, Papineau, Leman and Béïque families fonds). Le Canada (Montréal), 13 sept. 1933. Le Devoir, 12, 13, 14 sept. 1933. La Patrie, 12 sept. 1933. La Presse, 14 sept. 1933. Mme F. L. Béïque [Caroline Dessaulles], Quatre-vingts ans de souvenirs (Montréal, [1939]). Réal Bélanger, Wilfrid Laurier: quand la politique devient passion (Québec et Montréal, 1986). Pierre Beullac et Édouard Fabre Surveyer, Le centenaire du barreau de Montréal, 1849–1949 (Montréal, 1949). H. A. Bizier, L’Université de Montréal: la quête du savoir (Montréal, 1993). Can., Senate, Debates, 14 July 1905: 680–88; 26 March 1912: 760–61, 767; 17 March 1915: 115–24; 30 March 1915: 252; 8 April 1915: 375–78. Directory, Montreal, 1870–1935. Yvan Lamonde, Louis-Antoine Dessaulles, 1818–1895: un seigneur libéral et anticlérical ([Saint-Laurent [Montréal]], 1994). Québec, Ministère de l’Énergie et des Ressources Naturelles, “Registre foncier du Québec en ligne,” Montréal, Montréal-Ouest, Rouville: registrefoncier.gouv.qc.ca/Sirf (consulted 24 Oct. 2019). Quebec Official Gazette, 1924: 2964; 1931: 2925–26; 1933: 3379. J. J. Robillard, “Histoire du collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir (1853–1912),” CCHA, Sessions d’étude, 47 (1980): 35–53. Ronald Rudin, Banking en français: the French banks of Quebec (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1988). Robert Rumilly, Histoire de la Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal: des patriotes au fleurdelisé, 1834–1948 (Montréal, 1975).

Cite This Article

Marc Vallières, “BÉÏQUE, FRÉDÉRIC-LIGORI (baptized Frédéric-Liguory Beic),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/beique_frederic_ligori_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/beique_frederic_ligori_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Marc Vallières |

| Title of Article: | BÉÏQUE, FRÉDÉRIC-LIGORI (baptized Frédéric-Liguory Beic) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |