Source: Link

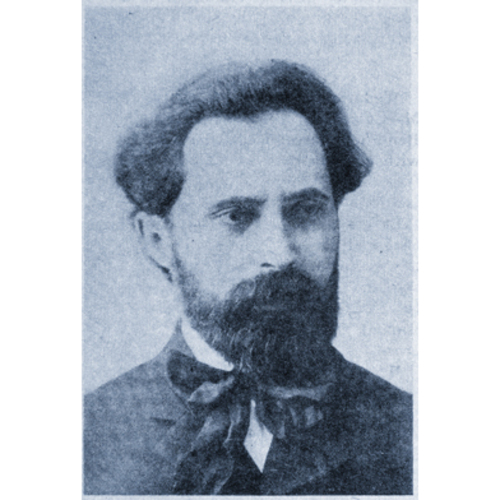

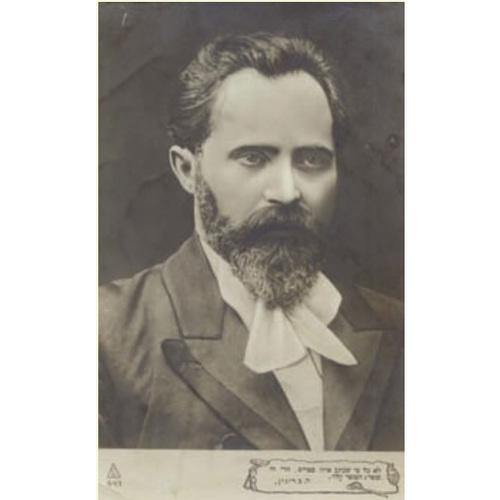

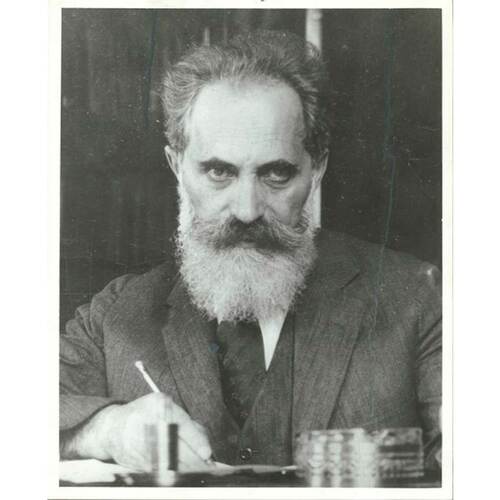

Brainin, Reuben (sometimes written as Reuven, Reuben Ben-Mordecai, or Ruvn Braynin), journalist, author, translator, editor, and Zionist thinker and activist; b. March 1862, probably on the 15th (n.s.), in Lyady (Belarus), son of Mordecai Brainin and Kheshe Rakhlin; m. 1888 Masha Amsterdam in Moscow, and they had two daughters and four sons, two of whom died in infancy; d. 30 Nov. 1939 in New York City.

Raised in czarist Russia’s Pale of Settlement (the western region in which Jews were permitted to reside), Reuben was a child prodigy who was immersed in traditional biblical and Talmudic studies. His inquisitive intellect led him to investigate medieval Jewish philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and Hebrew secular literature of the Jewish Enlightenment, known as Haskalah. He did so in secret since these subjects were considered a heretical deviation from the traditional Jewish religious curriculum.

In 1878, at age 16, Brainin taught himself Russian and began to read secular literature in that language, which was considered an act of rebellion by those around him. Influenced by a love of nature and productive labour, Brainin left home for Horki (Belarus) later that year to study at its agricultural school but was refused admission owing to antisemitism. In 1879 he moved to Smolensk, Russia, outside the Pale of Settlement, and for the first time came in close contact with non-Jewish Russian society. There, he mastered German and French.

Brainin debuted as a Hebrew writer in 1880 in Ha-Meliẓ [The Advocate] (St Petersburg), the chief Hebrew tribune of the Haskalah in Russia. Under the impact of the pogroms of 1881, he committed himself to the early Zionist movement Love of Zion. In 1887 he settled in Moscow and joined the influential student society Sons of Zion. He was a vigorous spokesman for the revival of Hebrew as the national language of the Jewish people and urged that it be used as a vernacular. To advance this purpose and popularize the Zionist ideal, he founded the Clear Language Society in 1888. That year he married Masha Amsterdam, the daughter of a Vitsyebsk (Belarus) rabbi. At the end of 1888 Brainin moved to St Petersburg for four months to become the literary editor of Ha-Meliẓ.

In 1891 Brainin and his family left Russia for Vienna, where he studied at the university and the Jewish theological seminary. He collaborated with writer Nathan Birnbaum in Zionist activity. In 1894 he began to publish his influential but short-lived Hebrew periodical Mi-Mizraḥ u-mi-Ma’arav [From East and West] (Vienna), which was devoted to the modernization and Europeanization of Hebrew literature. He wanted to broaden the boundaries of this literature to include all that is human, not just discussions of Judaism and Jewish history, and to situate Jewish culture in the context of western civilization.

In 1896 Brainin and his family settled in Berlin, where he studied at the university. He attended the first Zionist Congress the next year in Basel, Switzerland, and became an intimate of Zionist Theodor Herzl, whose biography he would write. Brainin published about 100 biographical sketches of Hebrew, Yiddish, and European writers. He also wrote fiction and translated several books into Hebrew, including Moritz Lazarus’s Der Prophet Jeremias [The prophet Jeremiah] in 1897, Herzl’s play Das neue Ghetto [The new ghetto] in 1898, and Max Nordau’s Paradoxe [Paradoxes] in 1900.

Brainin’s association with Canada’s first and most influential Yiddish daily, Keneder Adler [Canadian Eagle], published in Montreal, began even before he arrived in North America. Brainin started to contribute articles in November 1908. After coming to the United States for the first time the following year, he visited Montreal in January 1910 at the invitation of the Federation of Zionist Societies of Canada (FZSC) [see Clarence Isaac de Sola*], delivered lectures, and made the acquaintance of the community’s leaders and members of the Yiddish literary circle. Visits to Toronto, Ottawa, Niagara Falls, and Kingston followed. Brainin and his family travelled extensively in the United States and returned briefly to Europe in the early summer of 1910. Brainin came back to Montreal for a second visit, under the auspices of the FZSC, from the end of 1910 to the beginning of 1911. He and his family then lived for about a year in New York City, where he published his short-lived Ha-Dror [Liberty], a Hebrew-language weekly of high quality. With the demise of this periodical, Brainin faced financial difficulties and became pessimistic about the possibilities for advancing the use of Hebrew in the Jewish communities of North America.

It was at this time that Hirsch (Harry) Wolofsky*, the founder and publisher of the Adler, offered Brainin the post of editor. The paper had a circulation of 10,000 in 1910, cost one penny, and tended to support the federal and provincial Liberal parties. Up until this point, Brainin had expressed a negative attitude towards the significance and future of the Yiddish language and its literature. He likely accepted the offer out of financial need and because, according to Brainin, Wolofsky had promised to aid him in re-establishing a Hebrew tribune.

Brainin and his family settled in Montreal, which had a Jewish population of about 28,000 in 1912. There, he served as editor of the Adler from 3 March 1912 to 15 Dec. 1915, earning a weekly salary of about $50. The most illustrious writer ever to edit the newspaper, he became a charismatic activist in Montreal’s Jewish community on several fronts: literary, cultural, social, and political. He worked in close cooperation with his younger colleague, the noted Jewish scholar, educator, Hebraist, and pro-labour Zionist Judah (Yehudah) Kaufman (Kaufmann), later known as Even Shmuel (Shemuel), who introduced him to the Canadian labour-oriented Zionist party Poalei Zion and other mass organizations of eastern European Jewish immigrants in Montreal. Brainin was elected vice-president of the FZSC, and in 1914 he was a founder of Montreal’s most significant Jewish cultural institution, the Jewish Public Library and People’s University. He was also responsible for establishing the Hebrew Teachers’ Circle and the Hebrew Centre, whose mission was the propagation of Hebrew as a living language. As well, he laid the groundwork for the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society of Canada, which would be set up in 1920, after his departure from the city. The Brainin home (first on Park Avenue and then on Davaar Avenue in Outremont (Montreal)) was permeated with the spirit of European intellectualism and became a salon that attracted both local and international guests, such as the famous Jewish authors Sholem Aleichem and his son-in-law Isaac Dov Berkowitz. Visitors found Masha to be very outspoken, modern, and sophisticated.

Brainin was forced to confront the tumultuous labour struggles that rent the Jewish community during his stay in Montreal, particularly the general strike in the garment industry during the summer of 1912 [see Solomon Levinson]. About a third of the labour force and the overwhelming majority of the manufacturers were Jewish. As editor of the Adler, Brainin was criticized for not expressing unqualified support for the strikers. He explained that as a Zionist he believed in the unity of the Jewish people for the sake of their national revival. Although he sympathized with the labour cause, he saw good and bad on both sides and wished for a peaceful settlement and reconciliation for the sake of the common good. On numerous occasions he attempted to arbitrate between the union and the manufacturers in the garment industry.

Relief for the Jews of eastern Europe, the struggle for their civil and national rights, and Zionist aspirations in Palestine became critical issues for Canadian Jewry after the outbreak of the First World War. Brainin challenged the moneyed and assimilationist leaders of Jewish communities in Montreal, and elsewhere in Canada, on these issues. Seeing the need for a broadly based, democratically elected body that would represent the national and Zionist interests of Canadian Jewry and advocate for a fair distribution of relief funds to sufferers in eastern Europe, Brainin founded the Canadian Jewish Alliance in 1915. This organization would pave the way for the creation of the Canadian Jewish Congress four years later.

Relations between Brainin and Wolofsky had become strained; they held different opinions about the strategy for creating an organization to represent Canadian Jewry. As well, their personalities began to clash. Most of the journalists on the Adler’s staff went on strike in February 1915, and Brainin joined them. Wolofsky was infuriated and conducted a virulent campaign against Brainin, whose career at the Adler would end in December. That fall Brainin founded his own Yiddish daily, Der Veg [The Way] (Montreal), which was devoted to the Canadian Jewish Alliance, the struggle for the creation of the Canadian Jewish Congress, and the raising of standards of Jewish cultural life. Despite its high quality, it lasted only from 15 Oct. 1915 to 21 June 1916 – less than nine months. Exasperated by the stresses of community work and the dispute with Wolofsky, Brainin returned to New York City, where he edited the renewed Hebrew-language journal Ha-Toren [The Mast] from April 1918 until 1925, when it ceased publication owing to financial difficulties. He had begun writing for the liberal Zionist Yiddish daily Der Tog [The Day] (New York) in 1923. His close contact with the Jewish masses in Montreal and the United States led him to see the importance of Yiddish in the struggle against assimilation and the true esthetic and national value of its literature.

Although Brainin would live in New York City for the rest of his life, he never severed his connection with Montreal. He had been invited as a guest of honour to the founding session of the Canadian Jewish Congress in the city (16–19 March 1919). He had siblings, children, grandchildren, and close friends there, and he often visited the city and summered in the Laurentian Mountains.

Brainin was a greatly admired Hebrew writer and Zionist leader for about 50 years. In 1925–26 he visited Palestine, where he saw many difficulties. After his trip to the Soviet Union in 1926, he became an enthusiastic supporter of Jewish agricultural settlement in that country and particularly of Birobidzhan as a Jewish autonomous region, with Yiddish as its official language and the potential to become a Jewish Soviet Socialist Republic. Brainin believed that this commitment could coexist with his Hebraist, Palestine-focused Zionism. He did not publicly condemn the Soviet persecution of Zionists or the suppression of Hebrew language and literature and the Jewish religion. This stand received the strongest censure from the Zionist–Hebraist camp with which Brainin had been so intimately associated for the greater part of his life. He felt unjustly attacked, rejected, and alone in the last years of his life.

Brainin’s health began deteriorating in the early 1930s. By 1937 he was paralysed and unable to speak. His mind, however, was still clear, and with help he was able to write a little and continue preparing the third volume of a collection of his works, which would be published in 1940, the year after his death. His request to be buried in the Shaar Hashomayim Cemetery on Mount Royal, near his daughter Miriam Ortenberg (d. 1918) and his wife (d. 1934), was granted. In 1941 his sons carried out his wish to donate his personal library and archive to Montreal’s Jewish Public Library. His life in that city had been plagued by contradiction. Publicly, he dedicated all his energy, passion, and idealism to the upbuilding of all aspects of Jewish communal life. Yet in his diary he confided that he felt he had betrayed the essence of his self by abandoning Hebrew for Yiddish and collaborating with people he considered intellectually and morally inferior to him.

Reuben Brainin’s unpublished diaries are located at the Central Arch. for the Hist. of the Jewish People (Jerusalem). A collection of his works was published under the title Kol kitve Re’uven ben Mordekhai Brainin [Complete works of Reuben Ben-Mordecai Brainin] (3v., New York, 1922–40). It should be noted that this publication does not contain all of his writings since Brainin was able to edit and procure funding for only the first three volumes before his death. Much of his Hebrew work remains in scattered publications and in unpublished manuscripts. Brainin’s memoirs were published in Yiddish under the title Fun mayn lebns-bukh [From the book of my life] (New York, 1946). The first part of his biography of Theodor Herzl, Ḥaye Hertsel: bi-sheloshah ḥalaḳim [The life of Herzl: in three parts] appeared in New York (1919), but the subsequent parts were never published. Brainin translated several books into Hebrew, including Moritz Lazarus’s Der Prophet Jeremias [The prophet Jeremiah] (Breslau [Wrocław, Poland], 1894) under the title Yirmiyah ha-navi (Warsaw, 1897), Herzl’s Das neue Ghetto [The new ghetto] (Vienna, 1897) under the title Ha-Geto he-ḥadash: ḥizayon be-Arba’ ma’arakhot (Warsaw, 1898), and Max Nordau’s Paradoxe [Paradoxes] (Leipzig, Germany, 1891) under the title Paradoksim: peraḳim be-torat ha-nefesh (Piotrków Trybunalski [Poland], 1900).

FD, Shaar Hashomayim Cemetery (Montreal), 3 Dec. 1939. Jewish Public Library, Arch. (Montreal), Fonds 1010 (Reuben Brainin fonds). S. [I.] Belkin, Di Poyle Tsien bavegung in Kanade: 1904–1920 [The Labor Zionist Movement in Canada: 1904 to 1920] (Montreal, 1956). “The Canadian story of Reuben Brainin, part 1,” comp. and ed. David Rome, Canadian Jewish Arch. (Montreal), new ser., no.47 (1993). “The Canadian story of Reuben Brainin, part 2,” comp. David Rome, ed. Naomi Caruso and Janice Rosen, Canadian Jewish Arch., new ser., no.48 (1996). Naomi Caruso, “Reuven Brainin: the fall of an icon,” ed. Janice Rosen and Shirley Brodt, Canadian Jewish Arch., new ser., no.49 (2007). J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise, vols.4, 5. Getzel Kressel, Leksikon ha-sifrut ha-ivrit [Cyclopedia of modern Hebrew literature] (2v., Merhavia, Israel, 1965–67), 1: 350–53. Leksikon fun der nayer Yidisher literatur [Biographical dictionary of modern Yiddish literature], ed. Shmuel Niger and Yankev Shatski (8v., New York, 1956–81), 1: 466–69. Rebecca Margolis, Jewish roots, Canadian soil: Yiddish culture in Montreal, 1905–1945 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2011). Samuel Paz, “Re’uven Breinin be-Montriyal (1912–1916)” [Reuben Brainin in Montreal (1912–1916)] (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1983).

Cite This Article

Eugene Orenstein, “BRAININ, REUBEN (Reuven, Reuben Ben-Mordecai, Ruvn Braynin),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 16, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brainin_reuben_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brainin_reuben_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Eugene Orenstein |

| Title of Article: | BRAININ, REUBEN (Reuven, Reuben Ben-Mordecai, Ruvn Braynin) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2023 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | December 16, 2025 |