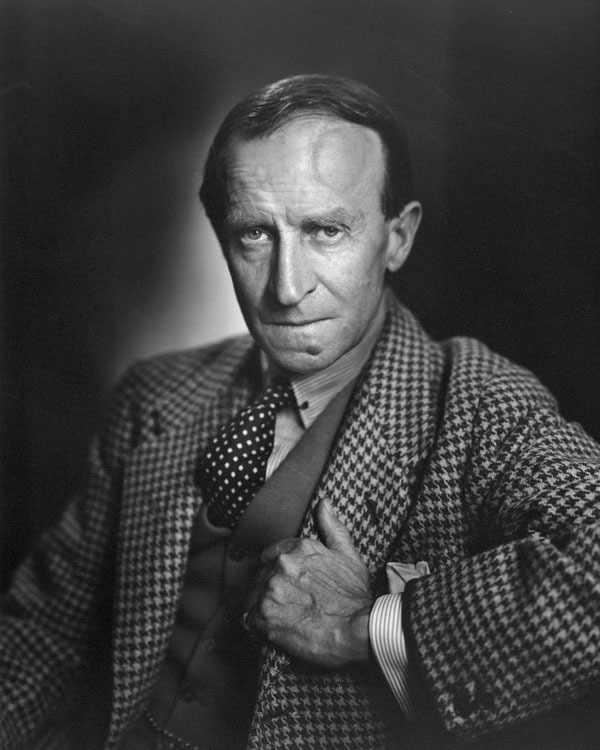

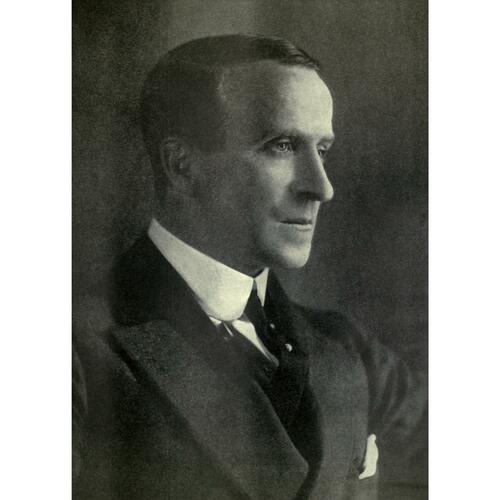

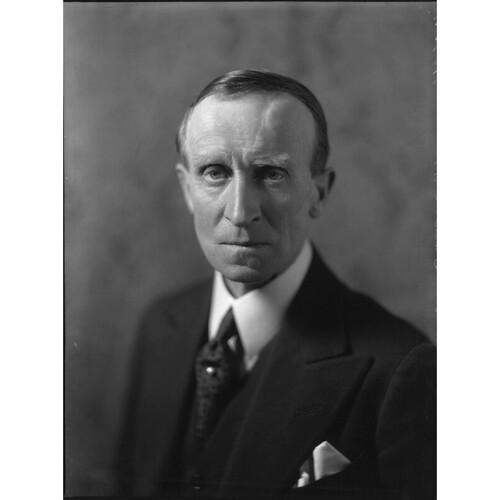

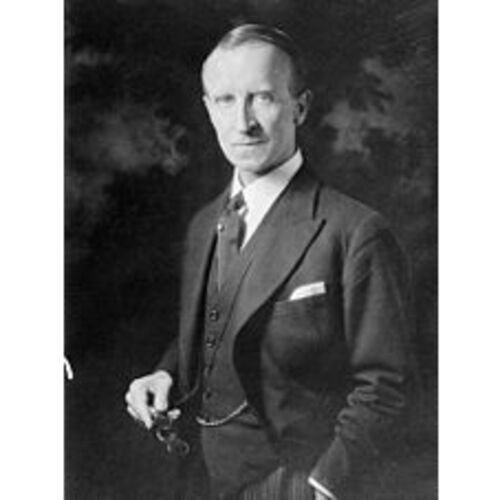

BUCHAN, JOHN, 1st Baron TWEEDSMUIR, author, editor, journalist, lawyer, civil servant, publisher, politician, and governor general; b. 26 Aug. 1875 in Perth, Scotland, son of the Reverend John Buchan, a minister in the Free Church of Scotland, and Helen Jane Masterton; m. 15 July 1907 Susan Charlotte Grosvenor (d. 1977) in London, and they had a daughter and three sons; d. 11 Feb. 1940 in Montreal.

John Buchan was the eldest of the five surviving children of religiously devout parents, whom he described as adherents of the “old Calvinistic discipline” tempered with an appreciation of “the goodness of the Lord.” His youth was spent on the east coast of Scotland, in inner-city Glasgow, and, during the long summers of childhood, with his mother’s relatives near Peebles, close to the English border. The distinctive landscape of the Borders region, with its high, rugged plateaus, rock-strewn hillsides, and stands of wind-blown trees, gained a firm grip on his imagination. “Woods, sea and hill,” he would write in his autobiography, “were the intimacies of my childhood, and they have never lost their spell for me.” In 1892, at the age of 17, Buchan went from a grammar school in Glasgow to the city’s university, where, he said, as a “wholly obscure” student he lived a life of “beaver-like toil and monkish seclusion.” Next he entered Brasenose College, Oxford, on a scholarship. There, between 1895 and 1899, he studied classical languages, literature, and philosophy while also developing the historical consciousness that would be the hallmark of his later life.

The young man showed remarkable precociousness with a pen and a keen interest in publication. At the age of 25 he had to his name three university prize essays, a collection of Francis Bacon’s writings, four novels, a history of his college, and two volumes of short stories set in the historic Scottish Borders. After leaving Oxford, Buchan arrived in London, where he read for the bar and worked as an editorial writer and book reviewer for the Spectator magazine. In June 1901 he was called to the bar. Two months later he accepted an offer to become a private secretary to Lord Milner, the high commissioner in South Africa. Milner recruited several young Oxford graduates – collectively known as his “kindergarten” – to help him integrate into the British empire the Boer republics defeated in the South African War. The project was politically controversial, and Buchan, who arrived in South Africa that October, was involved in tasks for which his talents were in demand, including management of internment camps and settlement of British farmers on land previously occupied by Afrikaners. His first major work of non-fiction, The African colony (1903), was a description of his experiences. It was in South Africa that he met the soldier Julian Hedworth George Byng, who would become a close friend and predecessor of Buchan in the office of governor general of Canada.

During his time in South Africa, Buchan acquired a profound sense of the independent spirit that was characteristic of the territories of the empire, and this understanding would be the foundation of his later work in Canada. As he later wrote in his autobiography, before living in South Africa he “had regarded the Dominions patronizingly as distant settlements of our people who were making a creditable effort under difficulties to carry on the British tradition. Now I realized that Britain had at least as much to learn from them as they had from Britain.… I began to see that the Empire, which had hitherto been only a phrase to me, might be a potent and beneficent force in the world.” Significantly, given the accusations of racism later levelled against his literary work, Buchan was also a firm supporter of the integration of Blacks in the political life of South Africa. He wrote that if the indigenous population became “a portion, however small, of the civic organism, there is hope for the future,” whereas, conversely, if they were treated as “a thing apart, denied the commonest of rights and remaining in their present stagnant condition, they will be a menace, political and moral, which no one can contemplate with equanimity.”

His experiences in South Africa led Buchan to rethink his career plans. He now dreamed of a career outside Britain that would allow him to play a role in shaping “this splendid commonwealth.” Still, after returning to England in late 1903, he set himself to the practice of law, despite feeling that the profession was “rather a pother about trifles.” In 1907, in St George’s Church, Hanover Square, the scene of many fashionable weddings, he married Susan Grosvenor. Through this relationship – the Grosvenors were related to the dukes of Westminster – he gained an entrée into the British establishment. It was to be a happy and harmonious partnership. After his marriage he abandoned the law to become a publisher. As an executive director in the Edinburgh firm of Thomas Nelson and Sons, which specialized in pocket editions for a mass readership, Buchan was responsible for generating new business, and in this role, which he held for a decade, he was associated with such leading writers as G. K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Rudyard Kipling, Thomas Hardy, and Henry James. He started writing fiction again in 1909, and in 1915, just after the start of the First World War, completed The thirty-nine steps, the tale of espionage for which he is still best known. Unfit for military service, Buchan worked as a Times (London) correspondent on the Western Front before joining the news department of the Foreign Office. To promote Britain’s cause around the world, he sent back detailed reports from France on the battle of the Somme and wrote a multi-volume series entitled Nelson’s history of the war, the first volume appearing early in 1915 and the last of the 24 at the end of 1919. In February 1917, drawing on his experience in publishing and journalism, he took the helm of Britain’s first Department of Information, which united within a single organization diverse agencies crafting propaganda aimed at allied, neutral, and enemy countries.

Buchan managed the national propaganda effort until the end of the war. In 1918 the department became a ministry under the control of Lord Beaverbrook [Aitken*], and it was closed on 31 December of that year. Meanwhile, Buchan continued his publishing activities and writing. Greenmantle (1916) and Mr. Standfast (1919) were set against the backdrop of the war, and The three hostages (1924) in the immediate post-war period. These and other contemporary and historical novels had established him as a significant literary figure by the early 1920s. Canny deals with publishers, including Houghton Mifflin in the United States, with which he had worked on wartime propaganda, gave him a substantial income from writing – enough to allow him to purchase, in 1919, a manor home in the village of Elsfield, close to Oxford’s “dreaming spires,” where he fancied himself “a minor country gentleman with a taste for letters.”

The war had altered Buchan’s outlook. He had lost many close friends, and his youngest brother, Alastair Ebenezer, was killed in 1917. At the Department of Information he had been keenly aware of the emerging struggle between authoritarianism and liberalism. He acknowledged that propaganda in democracies, however necessary to winning the war, tended to debase political ideas and impoverish political debate. Fearing that lasting damage might have been done to democratic political culture, Buchan determined to make amends. He perceived a profound and dangerous cultural shift as younger people rejected links with the past amid attempts to make the world anew. In a deliberate rebuke to those who thought they could do without the past, he pushed history up the public agenda. Under his direction, Thomas Nelson and Sons turned to educational publishing, with new-style textbooks under the umbrella titles The teaching of English series and The teaching of history series supporting the direction taken by national education policy after the war. Buchan’s close friendship with the popular historian George Macaulay Trevelyan led him to produce a collection of short stories, called The path of the king (1921), about turning points in history since the Middle Ages. Trevelyan’s own History of England set the standard for historical study at the secondary level in Britain for the next generation, and Buchan engaged Trevelyan as an adviser on The teaching of history series. In collaboration with the American publisher George H. Doran and, subsequently, the United Kingdom branch of Houghton Mifflin, Buchan also edited a series for the British company Hodder and Stoughton, entitled The nations of today, weaving into a national historical narrative new ideas of global interdependence based on the League of Nations charter at the end of the First World War.

On 29 April 1927, after an unsuccessful candidacy in 1911, Buchan was elected a member of parliament, representing the four Scottish universities. He was a Tory by conviction, with a strong pragmatic streak superimposed upon liberal instincts. He admired the political style of Stanley Baldwin, the Conservative leader, who invited Buchan to help the Conservative Party respond to the challenge of socialist ideas, which were increasingly influential among opinion makers and younger people. Following the creation of a national coalition in September 1931, Buchan sought a cabinet-level post, but Baldwin used him instead as a personal factotum to monitor the nation’s views and assist in shoring up the government. He emerged as a public intellectual, involved in campaigns for cultural causes. In 1933 and 1934 he was appointed by King George V as lord high commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. His success in this ceremonial role was among the factors that led to his appointment as governor general of Canada.

Buchan had first met the leader of Canada’s Liberal Party, William Lyon Mackenzie King*, in London in 1919. King was impressed by his ideas on dominion autonomy and by his non-conformist religious outlook. He also came to admire Buchan’s literary prowess and connections in Britain’s political establishment. They became better acquainted during King’s forays to Britain on imperial business in the 1920s, and when the Buchans paid a visit to North America in 1924, they stayed as King’s guests in Ottawa. Buchan had just published a biography of Lord Minto [Elliot*], who was the governor general of Canada when King was deputy minister of labour before the First World War, and King delighted in correcting some of its judgements. He saw Buchan as a kindred spirit, a view Buchan actively encouraged, sending King personally inscribed copies of his books. In 1926 King indicated that he would welcome Buchan’s appointment as governor general. The suggestion was unacceptable to London since it implied that Canada could choose its own governor general. A second opportunity arose in 1931 after the Statute of Westminster formally conceded independent status to the dominions under the crown. Britain’s political leaders believed that Buchan’s skill in shaping political culture should be put to work to ease Britain and Canada into their new relationship, encouraging the latter to develop a stronger national identity inside the British Commonwealth. Buchan’s friendship with King was now very much in his favour. With King’s active encouragement, Richard Bedford Bennett*, who had become Conservative prime minister in 1930, petitioned for Buchan’s appointment as governor general in March 1935, and this time the suggestion fell on receptive ears. The Liberal Party returned to power in the federal election that October, and Prime Minister King welcomed Buchan, newly ennobled with the title of Baron Tweedsmuir, as governor general of Canada on 2 November.

At the start of his term, Buchan clashed with King over the extension of honours, such as knighthoods, to Canadians. King and some of his supporters wanted the new governor general to be plain “Mr John Buchan,” and King was disappointed when Buchan’s “old world” preoccupation with the dignities of office – “a sort of royalty complex, which is damnable in my eyes,” as King put it – came between them. Yet their working relationship grew to be solid. Both were free traders, sharing the ambition to move away from the imperial protection that had been pursued by the Conservative government at the Imperial Economic Conference held in Ottawa in 1932. They collaborated to position Canada as a diplomatic bridge between London and Washington. On a state visit to Washington as governor general in March–April 1937, Buchan presented President Franklin Delano Roosevelt with a plan for bringing dictators in from the cold through economic diplomacy. This proposal was an outgrowth of King’s conviction that autarchy lay behind rising international tension. On another front Buchan’s careful attention to francophone Canada (he was fluent in French) became more important after the Liberal Party was defeated by the Union Nationale, led by Maurice Le Noblet Duplessis*, in the Quebec provincial election of 1936. Buchan made it his priority to stay close to King on all these matters. He was consistently King’s loyal apologist and was repaid with his confidence.

Buchan’s cultural purpose, which King also supported, was to develop within Canada what he called “a uniform national spirit.” His wife, Susan, who was also an author, pursued this goal by starting a program to supply library books to rural communities in the western provinces and encouraging Women’s Institutes to gather their local histories. Buchan gave public and private encouragement to Canadian writers, becoming honorary president of the Canadian Authors Association in 1935 and lending the title of his office for the national prizes in fiction and non-fiction that are still awarded today. He intended to contribute personally but underestimated the constraints of protocol on publication by the monarch’s representative. He threw himself into touring officially across Canada, often accompanied by members of the press whom he cultivated, and making numerous short speeches to clubs and professional groups. Never before had a governor general spoken so frequently or reached out to such varied audiences. Buchan wanted the publicity earned by his visits and speeches to increase Canadians’ understanding of the different regions of the country and the contribution each made to an enriched whole.

The pattern was established in 1936 with a tour of the prairie provinces, where the Great Depression, compounded by drought, had struck hardest. Buchan went off the beaten track to meet farmers, non-English-speaking immigrants, and the unemployed. Men in shirtsleeves and women with children in their arms came to his open-air receptions for homesteaders. The following year he began on the west coast and visited the drought-stricken areas of Alberta before voyaging down the Mackenzie River to the Arctic on a rear-wheel paddle steamer, visiting the mission stations and mines in the Canadian north, traversing by horse and canoe the national park in British Columbia that the federal government had named after him, and then touring the Maritime provinces. During his tours Buchan also reached out to Indigenous people. On at least five occasions he received the title of honorary chieftain, with names that included “Scribe,” “Teller of Tales,” and “Eagle Face.” In his memoirs he would include a photograph of himself as a chief of the Blood nation. Much ahead of his time, Buchan showed recognition for Canada’s Indigenous cultures and valued the contribution they had made to the modern nation.

Buchan delighted in the work. However, the ceaseless motion and lack of routine exacerbated the gastritis from which he had suffered since an unsuccessful operation on a stomach ulcer in 1917. In the hope of bringing his condition under control while on leave in Britain in the autumn of 1938, Buchan went for two months to a clinic specializing in gastric illnesses. Yet it became apparent shortly after he returned to Canada in November 1938 that his health had been affected permanently.

Buchan put monarchy’s mystique to good use, but in the late 1930s it also had to be preserved. At the end of 1936 he was faced with the crisis created by Edward VIII’s wish to marry an American divorcee. In the wake of the Statute of Westminster, dominion views were no less important than those in Britain, and Buchan’s reports, in line with King’s, on the shocked state of public opinion helped to discourage the idea that Edward could marry a divorcee and remain head of state. While in Britain in 1938, Buchan promoted the idea of a visit to Canada and the United States by the new king and queen, George VI and Elizabeth. Such a tour would be a golden opportunity to display solidarity among democracies while European dictators flexed their muscles. The event would also demonstrate that, under the new imperial constitution, the office of governor general was fundamentally transformed: it no longer stood between the monarch and Canada’s elected government, and it represented not the British government but the monarchy alone. When the royal party arrived in Canada in June 1939, Buchan absented himself so that the monarch could be seen to be attended solely by the head of the government elected by the people. But he advised the king and queen on how best to handle the press and on the use of ceremony to win hearts and minds. The tour was a huge success. Building on what Buchan had sought to achieve as governor general, it showed that the relationship between monarch and subjects had been reinvigorated through the transition from empire to commonwealth.

Political friends kept Buchan informed of growing tensions in British politics over the rising power of Germany. It is sometimes suggested that he was a firm supporter of Prime Minister Arthur Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement, but this is not entirely clear. Britain’s rearmament was just beginning as Buchan left for Canada. Through his friendship with Roosevelt, he assisted the foreign secretary, Robert Anthony Eden, until Eden’s resignation early in 1938, in rebuilding solidarity with the United States as part of a stiffening of democracy’s sinews. He also shared the views of Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery, another prominent anti-appeaser, on the horrors of the Nazi regime. As a parliamentarian in Britain, Buchan had chaired a backbench committee advocating the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. This brought him into contact with prominent figures in the Zionist movement, including Chaim Weizmann. Buchan was keenly aware of the growing violence against dissidents and minorities in Germany, which he likened to the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of Huguenots in France in the 16th century. He promoted the idea that Canada should accept refugees, although the Canadian government took a cautious view and only limited numbers came. Buchan did encourage Chamberlain in his peace initiative at Munich in November 1938, although this simply echoed the policy of Prime Minister King, who had met Hitler and urged Chamberlain to treat with him. In any case, what objection could there be to giving peace one more chance if it fostered Canada’s solidarity with Britain when war came?

When Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939, the role Buchan had created for himself in the country’s political life was effectively ended. Commercial duties continued, but there was now much less call to shape views about Canada. The British high commissioner in Ottawa described his appearance as he presided in the Canadian Senate at the declaration of war; he was “a somewhat frail and tired looking figure dressed in black upon the red Throne.” Buchan declined the offer of a second term as governor general, explaining that he needed to take a prolonged rest cure back in Britain. Books ready for publication when he relinquished office included a collection of stories presenting Canada’s history for children, called The long traverse, an adventure story set in northern Quebec, Sick Heart River, and an autobiography, Memory hold-the-door.

On 6 Feb. 1940, six months before his term was due to end, Buchan fell in his bathroom at Rideau Hall, the governor general’s residence in Ottawa. The fall was caused by a clot in an artery of his brain, and the damage was compounded by concussion. Taken to Montreal for emergency surgery (one of his doctors was Wilder Graves Penfield*), he died at the Neurological Institute at McGill University on the evening of 11 February. The relationship Buchan had established with Canadians was evident when thousands of ordinary people paid their respects at his funeral at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church in Ottawa. King, for his part, said that Buchan’s knowledge of history and intuitive grasp of free British institutions had made him the perfect governor general: “From the correct conception of that high office, he never departed in thought, word, act or deed.” Stanley Baldwin described how his friend had “spent himself and was spent on work far harder and more exhausting than the ordinary ceremonial work of His Majesty’s representative.” Buchan’s remains were cremated in Montreal and then returned to Britain for burial in the Anglican churchyard at Elsfield. Memorial services were held in London at Westminster Abbey and in Oxford, Edinburgh, and Glasgow. The Latin inscription on his gravestone in Elsfield was supplied by Sir Dougal Orme Malcolm, who had been a contemporary at Oxford and fellow member of Milner’s “kindergarten.” It reads: “Qui musas coluit patriae servivit amicis delectum innumeris hic sua terra tenet” (Here, in his own earth, lies a man of letters, who served his country and enjoyed the affection of countless friends).

Buchan is usually remembered for a single book, The thirty-nine steps, which is sometimes credited with establishing the thriller genre. Yet he was a prolific – even obsessive – writer with a substantial output in other literary forms. He produced more than a dozen historical novels as well as almost 20 volumes of contemporary fiction – those with Richard Hannay as the hero are perhaps best known – and more than 50 short stories, some with a supernatural setting, which were published individually in magazines before appearing in collections. In non-fiction, Buchan wrote contemporary history and historical biography, including full-length portraits of Oliver Cromwell, Sir Walter Scott, and the Roman emperor Augustus. He was also an essayist and poet, and his fine autobiography, Memory hold-the-door, appeared posthumously. He even tried his hand at fiction for children, drama, and film scripts. In all, he has 70 published titles to his name. The modern critic Christopher Eric Hitchens described Buchan’s urge to write, alongside a busy public life and work as a journalist and publisher, as amounting to “graphomania.”

Buchan is hard to place as a writer. Much of his work, notably his descriptions of landscape and weather and his writing about Scotland with use of vernacular speech, is of the highest quality. However, the extent of his output and the range of his literary interests have diminished his standing in the eyes of some critics. Buchan is sometimes presented as a transitional figure, situated between, for example, the literary decadence of the 1890s and the pulp-magazine fiction of the early to mid 20th century, and between Rudyard Kipling and Ian Fleming. He was not a self-consciously literary figure, and his considerable earnings from writing were a source of envy in others. There has been growing recognition that some of the books that were particularly popular in his own time were written as propaganda, to raise morale and to promote particular cultural and political ends. Buchan was adept at making polemics attractive to readers, and these books have often successfully transcended their original purpose through their entertainment value. But it was in his writing on a smaller scale, in the short stories and essays in which he learned his craft, that Buchan most revealed himself. One commentator writing in the late 1980s described the best of his fiction as “containing a sense of an uncanny world beneath the veneer of civilisation – a world both fascinating and terrifying.”

In an essay published in 1968, the American historian Gertrude Himmelfarb described John Buchan, not without a certain admiration, as “the last Victorian.” There were contemporaries who accused him of snobbery and the worship of success, and post-war critics added a charge of antisemitism. His personal reputation, which also suffered from its close association with imperialism, is now much restored. It is true that his writing did express the values of earlier times. Yet his purpose was less literary than political, and his achievements were more in tune with the second half of the 20th century than with the mid-Victorian period. His mission to Canada was only his last project to modernize antique institutions so that an old magic could work for new generations. Skill with a pen and friendship with influential figures in politics and the arts were his instruments. He was animated by a profound belief in democratic values and the good judgement and creativity of ordinary people. His close friend Leopold Amery described Buchan’s interest in his fellow human beings as all-comprehending: “Whatever their class, creed, race, colour or place in space or time, his intense sympathy and vivid imagination saw in them something to admire, usually to love, always to enjoy.” Buchan was a cultural warrior who achieved a rare harmony of aim and method. This accomplishment may help to explain why the best of his fiction is still read many decades after his death.

John Buchan is the author of The African colony: studies in the reconstruction (Edinburgh and London, 1903), Prester John (London and Toronto, [1910?]), Nelson’s history of the war (24v., London, [1915–19]), The thirty-nine steps (Edinburgh and London, 1915), Greenmantle (London and Toronto, 1916), Mr. Standfast (Toronto, 1919), The path of the king (London, [1921]), Lord Minto: a memoir (London, 1924), The three hostages (London, [1924]), Augustus (London, 1937), Memory hold-the-door (London, 1940), The long traverse (London, 1941), and Sick Heart River (London, 1941). Buchan also edited The nations of today: a new history of the world (12v., London, 1923–24).

Three collections of essays and short biographies, which originally appeared in literary magazines, were published in Buchan’s lifetime: Some eighteenth century byways and other essays (Edinburgh and London, 1908), Homilies and recreations (London and Edinburgh, 1926), and Men and deeds (London, 1935). A collection of articles he wrote for the Scottish Rev. (Paisley, Scot., and London) appeared in 1940 under the title Comments and characters, ed. and intro. W. F. Grey (London and Toronto). His speeches, given while he was governor general, were compiled in Canadian occasions: addresses (London, 1940). A bibliography of his uncollected journalism was published in Roger Clarke, The journalistic career of John Buchan (1875–1940): a critical assessment of its context and significance (Lewiston, N.Y., [2018]).

The largest collection of Buchan’s papers, including many of the books from his library at Elsfield, is in the W. D. Jordan Rare Books & Special Coll., Queen’s Univ. Library (Kingston, Ont.), in the John Buchan coll. Other archival records are scattered in various archival fonds/series at the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh (Buchan family papers and collections brought together by his authorized biographer, J. A. Smith) and in the Edinburgh Univ. Library, Special Coll., Coll-25 (Records of Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd), Buchan corr. (Gen. 1728/B/1-14). Buchan had a wide circle of correspondents among his contemporaries in literature, politics, and publishing. His letters crop up in many other collections in Britain and North America, such as the Leopold Amery papers (GBR/0014/AMEL) at the Arch. Centre, Churchill College, Univ. of Cambridge, Eng., the papers of Stanley Baldwin at the Dept. of Manuscripts and Univ. Arch., Cambridge Univ. Library (Eng.), and the various papers of Ferris Greenslet held in several collections by the Houghton Library, Harvard Library, in Cambridge, Mass.

R. G. Blanchard, The first editions of John Buchan: a collector’s bibliography (Hamden, Conn., 1981). Ursula Buchan, Beyond “The thirty-nine steps”: a life of John Buchan (London, 2019). J. W. Galbraith, John Buchan: model governor general (Toronto, 2013). Gertrude Himmelfarb, “John Buchan: the last Victorian,” in her Victorian minds (New York, 1968), 249–72. Andrew Lownie, John Buchan: the Presbyterian cavalier (London, 1995). J. P. Parry, “From the Thirty-nine Articles to ‘The thirty-nine steps’: reflections on the thought of John Buchan,” in Public and private doctrine: essays in British history presented to Maurice Cowling, ed. Michael Bentley (Cambridge, Eng., 1993), 209–35. Reassessing John Buchan: beyond “The thirty-nine steps,” ed. Kate Macdonald (London and Brookfield, Vt, 2009). J. A. Smith, John Buchan: a biography (London, 1965).

Cite This Article

Michael G. Redley, “BUCHAN, JOHN, 1st Baron TWEEDSMUIR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/buchan_john_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/buchan_john_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michael G. Redley |

| Title of Article: | BUCHAN, JOHN, 1st Baron TWEEDSMUIR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2023 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |