Source: Link

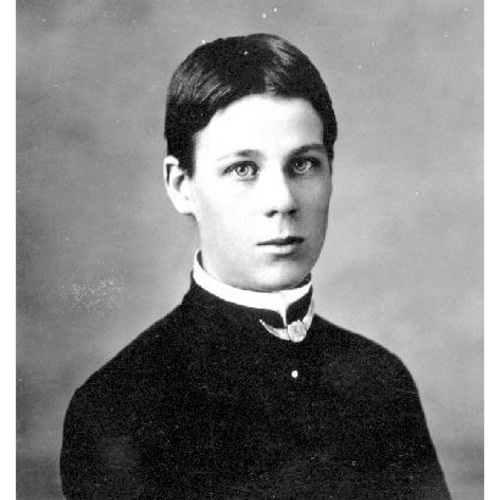

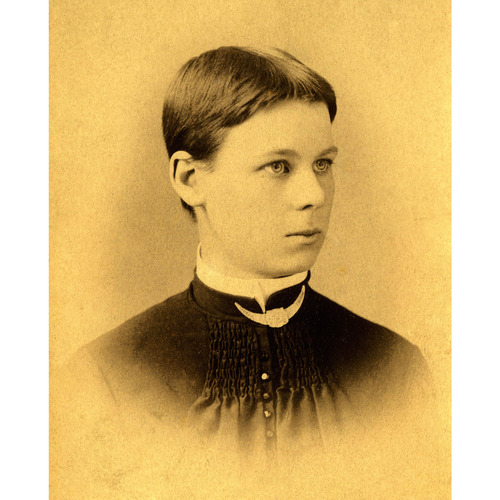

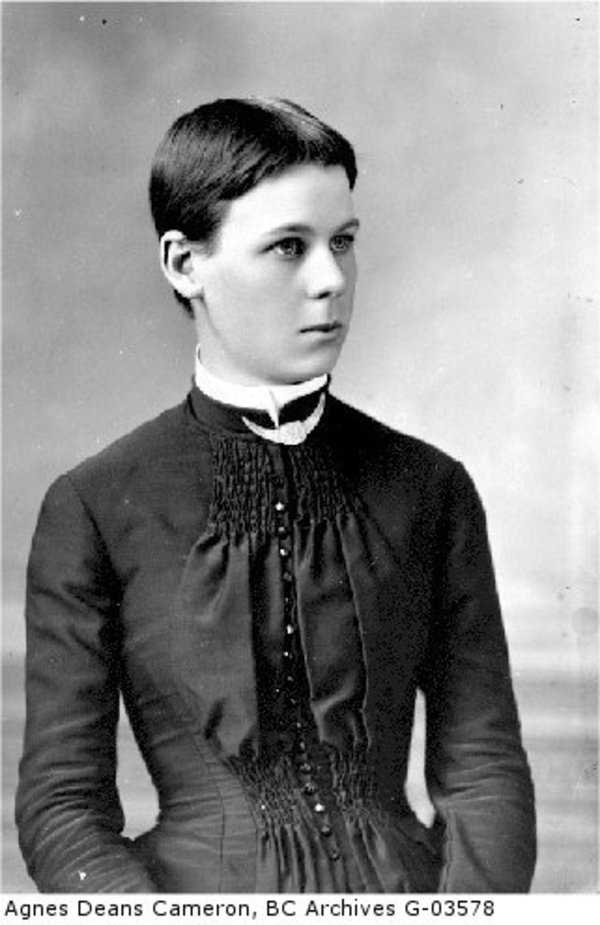

CAMERON, AGNES DEANS, educator, writer, lecturer, and adventurer; b. 20 Dec. 1863 in Victoria, daughter of Duncan Cameron, a miner and contractor, and Jessie Anderson; d. there unmarried 13 May 1912.

The youngest child of successful Scots immigrant parents, Agnes Deans Cameron might well have been expected to follow the conventional route for women of her generation and background: marriage and motherhood. But Cameron’s personality, intellect, and outlook guided her towards paths less familiar to women. Along the way her many talents won her wide recognition.

Cameron’s initial choice of a teaching career was not an unusual one for a young Canadian woman in 1880. Her distinction lies in her level of achievement in the patriarchal public school system of British Columbia and her contributions to the western Canadian debates about education. At 16, while still a student at the Victoria High School, Cameron successfully completed the provincial teachers’ examinations and acquired a certificate which qualified her to teach in any public school in the province. Following a short stint at the private Angela College for girls in her home town, she launched her public teaching career in 1882 at the one-room school in Comox. By the new year she had managed to vacate this dismal situation in favour of a better paid and less isolated one in Granville (Vancouver). In September 1883, only a year after her departure from Victoria, she returned to take up the position of third assistant at the Girls’ School. In the much more advantageous locale of the capital she seized opportunities to improve her skills, raise her profile, and advance her position. The success of her strategy is apparent in her steady rise through the ranks of the Girls’ School, to the Boys’ School, and then on to the more prestigious High School as its first female teacher. In 1894 Cameron was appointed principal of the new South Park School, the first woman to hold an administrative office in a co-educational school in Victoria.

Cameron’s ability to break the barriers in her profession is largely attributable to her high profile. Locally, she enjoyed a reputation as an excellent teacher among fellow instructors, parents, students, and the wider community. Provincially, she was well known as a founder and long-term executive member of the British Columbia Teachers’ Institute; through its annual conferences she communicated her views on topical issues, including the right of women to participate fully and equally in all aspects of the teaching profession. Nationally, Cameron contributed to the discussion as president of the Dominion Educational Association in 1906.

Her association with the BCTI and the smaller Victoria Teachers’ Institute provided her with a forum in which to develop her ideas about the purpose and character of education. She held forth on these subjects from podiums and in print, becoming associate editor in 1902 of the Manitoba-based Educational Journal of Western Canada. She argued staunchly in favour of a liberal education curriculum which would provide students with the analytical skills necessary to become citizens. This view brought her into sharp conflict with groups that favoured the introduction of applied courses such as home economics, industrial arts, and agricultural training to prepare children for jobs. Similarly, she opposed the imposition of school-based programming to support social causes such as temperance on the grounds that this kind of instruction belonged in the home and at church. Her opposition to an applied curriculum is tied to her belief in the value of each individual. She advised, “If you are a parent or a teacher, don’t strive to fashion your children into one stereotyped pattern. A child’s individuality is the divine spark in him. Let it burn.” Schooling, she contended, should enable children to develop self-esteem and originality tempered by an awareness of the necessity for responsible behaviour at all times.

Cameron brought the same principles to the world beyond the classroom. Her support of causes such as women’s suffrage, pay equity, and eliminating age discrimination was based on the ideas of “simple justice” and meritocracy. She rejected the claims of the maternal feminists to female moral superiority in favour of the liberal humanist argument. “Anyone with reason has a right to help in determining what laws shall govern him,” she maintained. “Women have reason, and, therefore, should vote.” Cameron’s commitment is connected to her definition of citizenship, which required all adults to recognize a duty to participate in public life through the exercise of the franchise and through volunteer work. Cameron belonged to a range of social reform organizations including the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Local Council of Women of Victoria and Vancouver Island, the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association, and the Children’s Aid Society. Her membership in these organizations was not always harmonious if their policies conflicted with her principles, as when the Local Council of Women offered to provide furnishings for a home economics class.

A woman who encouraged students to “ring true and stand for something,” Cameron applied this injunction as rigorously to herself. Three times her educational career fell under public scrutiny. The first incident arose in 1890 over allegations that Cameron had inappropriately disciplined a student. The dispute was quickly settled on her terms. A second and more serious incident occurred in 1901. Cameron and Mary Williams, both female principals in the Victoria school system, were suspended for insubordination. They were accused of contravening a new policy which had replaced written examinations with oral ones. Williams apologized immediately and was reinstated. Cameron remained implacable. The high level of support for her among Victoria residents resolved the issue in her favour, but not without a legacy of ill will on the part of some of the school trustees.

Enormous community support was not enough to save Cameron’s career in the third controversy. In the summer of 1905 she and her school’s art teacher were accused of allowing their students to cheat on the high school entrance examinations by permitting the use of rulers in a freehand drawing exercise. Cameron denied that any wrongdoing had occurred and took umbrage at the implied criticism of the children’s morals. The public uproar in the wake of Cameron’s subsequent dismissal prompted the school board to request a royal commission of inquiry into the matter. Meanwhile, Cameron capitalized on the public sentiment in January 1906 by contesting a seat in the elections for school trustees, winning more votes than any other candidate. The manœuvre was not, however, sufficient to forestall disaster. The royal commission found against her and in April her first-class teaching certificate was suspended for three years. Her career in education was over.

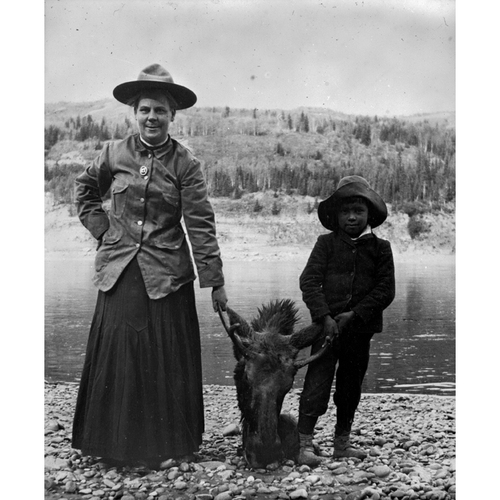

Always resourceful, Cameron turned to her writing to support herself. In the summer she joined the Canadian Women’s Press Club, a small band of professional women journalists formed in 1904 by Kit Coleman [Ferguson], Robertine Barry*, and others. Membership provided Cameron with the connections she needed. Almost immediately she accepted a commission to do publicity work for the Western Canada Immigration Association from its headquarters in Chicago. She was assigned to use the popular press to attract Americans and eastern Canadians to the Canadian west. In this context she formulated her great plan to travel from Chicago across the “Belt of Wheat” and the “Belt of Fur” to the Arctic Ocean. In the spring and summer of 1908 she and her niece Jessie Cameron Brown journeyed north to the delta of the Mackenzie River, accompanied by Cameron’s ever-present typewriter and Kodak camera, other necessary equipment, and a series of local guides and outfitters. They returned triumphant, having travelled 10,000 miles, the first white women to reach the Arctic Ocean overland. Throughout the autumn and winter, while revising her travel manuscript, Cameron undertook an extensive speaking tour of the American Midwest. She offered her audiences a series of four travel talks illustrated with lantern slides primarily from her legendary journey. The titles, “Wheat – the wizard of the north,” “From wheat to whales,” “The witchery of the Peace,” and “Vancouver’s isle o’dreams,” were calculated to present an enticing view of prospects in Canada. Cameron’s shows were also popular in Toronto, where members of the local élite clamoured to shake her hand. Never one to shy away from public view, she wrote numerous articles featuring highlights of her trek. After the publication in 1910 of her informative and witty travelogue, The new north, Cameron journeyed to England on a newspaper assignment which she combined with a two-year stint for the Canadian government to promote immigration. While there she was welcomed as a member of the Institute of Journalists.

Cameron returned to Victoria just before Christmas 1911. Her celebrity ensured her of good coverage in the press. Anxious not to miss an opportunity for civic promotion, the city council had voted to host a reception for her. Similarly, the executive of the local Political Equality League invited her to join the platform party for the visit of the noted English suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst. But Cameron had little opportunity to enjoy or exploit her local popularity. On 13 May 1912, at the age of 48, she succumbed to pneumonia after undergoing an appendectomy only a few days before. Lauded as a woman who possessed “an intellect that was almost masculine in its massive proportions,” she might have thought her work unfinished.

[Agnes Deans Cameron’s travelogue, The new north: being some account of a woman’s journey through Canada to the Arctic, was published in New York in 1910; a revised edition, . . . : an account of a woman s 1908 journey . . . , ed. D. R. Richeson, appeared in Saskatoon in 1986. A second book, The outer trail (1910), is attributed to Cameron in Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912) and a number of other sources, but there is no substantive evidence for its existence. It is not listed in standard bibliographic sources and no reviews have been found; in addition, none of the public relations material written by Cameron’s contemporaries refers to it. l.l.h.]

Journal articles by Cameron include “The idea of true citizenship – how shall we develop it?” Educational Journal of Western Canada (Brandon, Man.), 1 (1899–1900): [229]–35; “Parent and teacher,” National Council of Women of Canada, Report (Ottawa), 1900: 91–98 (discussion, 99–100); “Parent and teacher,” Educational Journal of Western Canada, 2 (1900–1): 454–56 and [485]–87; “In the motherland,” Educational Journal of Western Canada, 3 (1901–2): [261 ]; “To success – walk your own road” and “The old Broughton Street school,” in Educational Journal of Western Canada, 4 (1902–3): 10–11 and 136–39; “The avatar of Jack Pemberton” and “Edmonton, the world’s greatest fur market,” in Pacific Monthly (Portland, Oreg.), May 1903: 305–10 and February 1907: 205–15; “Beyond the Athabasca,” Westward Ho! (Vancouver), 5 (July–December 1909): 743–50; and “The fate of four mounted police on the Great Divide,” Graphic (London), 29 April 1911: 624.

Cameron’s photographs of her activities, including her Arctic journey, are preserved in two collections: BCARS, Visual Records Unit, pdp 98107–21, 98207–8, and Univ. of Victoria Library, Arch. and Special Coll., 86-P-3.

BCARS, S/D/C 14; Vert. file, A. D. Cameron. NA, MG 28, I 232. North York Public Library (North York, Ont.), Canadiana Coll., Newton MacTavish coll. (mfm. at NA, MG 30, D278). Daily Colonist (Victoria), 1890–1912. Manitoba Weekly Free Press (Winnipeg), 1906. Victoria Daily Times, 1901–12. B.C., Legislative Assembly, Sessional papers, 1882–1907, reports on the public schools, 1880/81–1905/6. Elizabeth Forbes, Wild roses at their feet: pioneer women of Vancouver Island ([Victoria], 1971), 53–54. Lyn Gough, As wise as serpents: five women & an organization that changed British Columbia, 1883–1939 (Victoria, 1988). L. L. Hale, “The British Columbia woman suffrage movement, 1890–1917” (ma thesis, Univ. of B.C., Vancouver, 1977). Gwen Hayball, “Agnes Deans Cameron, 1863–1912,” British Columbia Hist. News (Vancouver), 7 (1973–74), no.4: 18–25. In her own right: selected essays on women’s history in B.C., ed. Barbara Latham and Cathy Kess (Victoria, 1980). Ada McGeer, “Agnes Deans Cameron . . . a memory,” British Columbia Hist. News, 8 (1974–75), no.1: 16–17. National Council of Women of Canada, Report (Ottawa; Toronto), 1895–1906. P. L. Smith, Come give a cheer: one hundred years of Victoria High School, 1876–1976 (Victoria, 1976). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.2. Who’s who in western Canada . . . , ed. C. W. Parker (Vancouver), 1911.

Cite This Article

Linda L. Hale, “CAMERON, AGNES DEANS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cameron_agnes_deans_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cameron_agnes_deans_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Linda L. Hale |

| Title of Article: | CAMERON, AGNES DEANS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |