Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

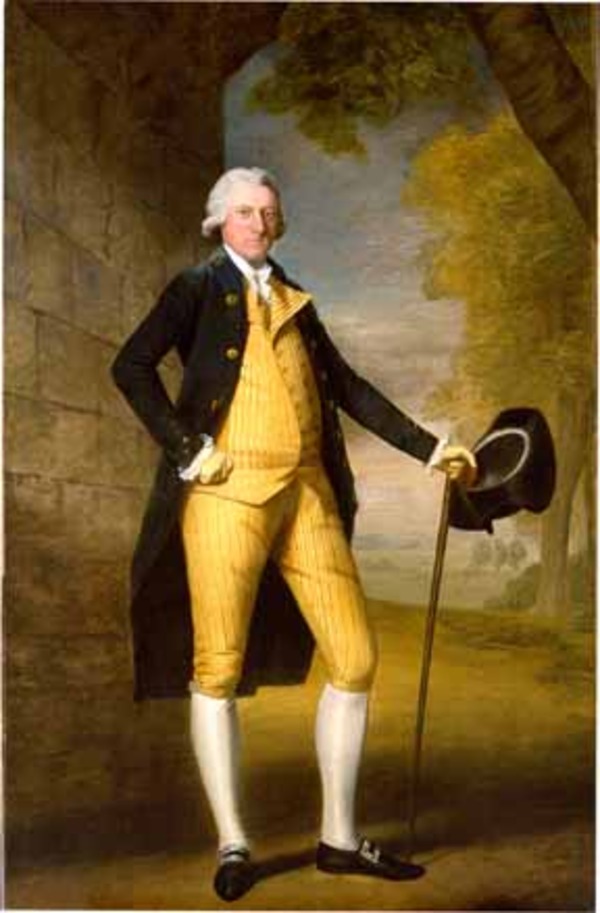

CHRISTIE, GABRIEL, army officer and seigneur; b. 16 Sept. 1722 at Stirling, Scotland, son of James Christie, a merchant, and Catherine Napier; d. 26 Jan. 1799 in Montreal (Que.).

Unlike his two brothers, a solicitor and a banker in Stirling, Gabriel Christie chose a military career, and his rise was like that of many sons of middle class families who were drawn towards the aristocracy. On 13 Nov. 1754 he became a captain in the 48th Foot. He took part in the siege of Quebec as a major, a rank he obtained on 7 April 1759. Christie was still in the colony when he was promoted lieutenant-colonel in 1762. In 1764–65 at the time of Pontiac*’s uprising, Christie as deputy quartermaster general used the public corvée to transport military supplies from Montreal to Lachine, the loading point for Detroit and Michilimackinac (Mackinaw City, Mich.). This action brought him into conflict with the governor, Murray, who objected to using the corvée now that civil government had been established; the incident was only one example in a series of quarrels that developed between Murray and the military [see Ralph Burton*] and reveals Christie as having personal ends in view in the use of his official position.

In 1776 the post of quartermaster general was assigned to Thomas Carleton*, brother of Governor Guy Carleton*. Christie protested but received the reply that he would have a better chance for advancement if he were in England. Christie did, indeed, go back there at this time. The following year he was promoted colonel. His battalion was stationed in the West Indies during most of the American revolution, but in the 1780s, when his active role in the army was over, he had settled upon Canada as his place of residence though he continued to make trips back to England. On 19 Oct. 1781, before the end of the revolution, he became major-general, and on 10 May 1786 was made colonel commandant of the 1st battalion of the 60th Foot. Nor was this his last promotion, for on 12 Oct. 1793 he became lieutenant-general and on 1 Jan. 1798 general. In other words, Christie’s military career was notable although not one of brilliant feats of arms. His portrait would be incomplete, however, if his activities as a large landowner were not taken into consideration.

Unlike Henry Caldwell*, who also had an interest in becoming a landowner and who consequently partook of the same upper-class mentality, Christie does not seem to have been attracted to the fur trade. He had a substantial fortune when his plans began to centre upon life in Canada, and he preferred to use it for landed property. The economic situation favoured his plans. After 1760 many seigneurs, both noble and bourgeois, were prepared to sell their fiefs because they were returning to France or were in financial difficulties. Christie’s conduct, which was socially significant, was also motivated by economic considerations: rapid population growth, large forest reserves in the seigneuries, and the beginnings of commercial prospects in the agricultural sector. In September 1764 he bought the seigneury of L’Islet-du-Portage from Paul-Joseph Le Moyne de Longueuil, a good long-term investment. Christie, however, was more interested in having land in the District of Montreal and thus he sold this seigneury to Malcolm Fraser* in 1777. In 1764 he and Moses Hazen* had acquired the seigneuries of Bleury and Sabrevois from the Sabrevois de Bleury family for £7,300. After a dispute with his partner, Christie temporarily lost part of the seigneury of Bleury to Hazen, but court battles between the two were far from over. In 1764 Christie bought the seigneury of Noyan from the Payen de Noyan family, sharing ownership with John Campbell. In 1765 the seigneury of Lacolle, owned by the Liénard de Beaujeu family, fell into his hands, and the following year he acquired the seigneury of Léry from Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry. Around 1777 he added the seigneuries of Lachenaie and Repentigny to his lands. These acquisitions were not enough to satisfy his ambition, even though he also owned land in England. In April and October 1792 he made two requests for land grants in the Eastern Townships, but evidently without success. Then on 23 Nov. 1796 Jean-Baptiste Boucher de Niverville sold him the seigneury of Chambly.

Christie lived partly on his seigneurial dues, which he said brought him £700 in 1790. Since he resided in Montreal and since his military career sometimes took him out of the country, he visited his seigneuries only occasionally and administered them through agents, but he had some concern for his rural property, valued at £20,000 in 1775. A dispute with the censitaires of Lachenaie over the right of banality revealed a man who was both alive to his interests and open to compromise. His attitude was paternalistic but also stemmed from a sense of his own importance. He remained interested for a long time in the exploitation of the forest resources of his seigneuries. As early as 1766 he travelled to Lake Champlain and afterwards began trading in forest products. Indeed the “seigneur” was, for a time, also a businessman.

Christie believed above all in the need to safeguard the integrity of patrimonies. Consequently he supported Francis Maseres*’ projected reform to secure greater freedom in making wills. He personally favoured his male offspring when he wrote his will. When he died in 1799 his lands went to his son Napier, who on his death in 1835 left them to his half-brother William Plenderleath*, on condition that Plenderleath take the name of Christie. Gabriel Christie was typical of a number of immigrant British officers who in their way of thinking closely resembled the nobility of New France.

Christie and his wife Sarah Stevenson had a son Napier and two daughters: Catherine, born 15 Jan. 1772, and Sarah, born 20 Nov. 1774, who married the Reverend James Marmaduke Tunstall, rector of Christ Church in Montreal. He also had a natural son, James, and with his mistress Rachel Plenderleath, three other sons, Gabriel, George, and William: all of these he recognized on 13 May 1789 when he made his will in Leicester, England.

PAC Rapport, 1890, 17–18, 76–79, 260; 1891, 15, 19–20. Quebec Gazette, 26 May 1785. P.-G. Roy, Inv. concessions, I, 261, 267; II, 200; IV, 242–43, 245, 253, 261, 265. Ivanhoë Caron, La colonisation de la province de Québec (2v., Québec, 1923–27), II. A. S. Everest, Moses Hazen and the Canadian refugees in the American revolution (Syracuse, N.Y., 1976). Nearby, Quebec, 40–41, 60–61. J.-B.-A. Allaire, “Gabriel Christie,” BRH, XXIX (1923), 313–14. F.-J. Audet, “Gabriel Christie,” BRH, XXX (1924), 30–32. P.-G. Roy, “Un amateur de seigneurie, Gabriel Christie,” BRH, LI (1945), 171–73.

Cite This Article

Fernand Ouellet, “CHRISTIE, GABRIEL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/christie_gabriel_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/christie_gabriel_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Fernand Ouellet |

| Title of Article: | CHRISTIE, GABRIEL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | January 19, 2026 |