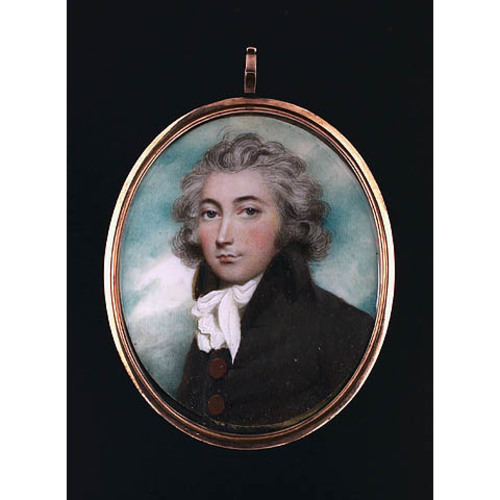

CLAUS, WILLIAM, army and militia officer, Indian Department official, office holder, jp, and politician; b. 8 Sept. 1765 at Williamsburg (formerly Mount Johnson), near present-day Amsterdam, N.Y., son of Christian Daniel Claus* and Ann (Nancy) Johnson; m. 25 Feb. 1791 Catherine Jordan, daughter of Jacob Jordan*, and they had three sons and two daughters who survived to adulthood; d. 11 Nov. 1826 in Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake), Upper Canada.

A man of modest abilities, William Claus was fortunate to be born into a family of prominence, wealth, and influence. His maternal grandfather, Sir William Johnson*, had vast estates in the Mohawk valley and was superintendent of northern Indians. His father held important positions in the Indian Department also. Claus’s family had intended to give him a proper education in a New York City school but was prevented from doing so by the outbreak of civil war and rebellion in colonial America, which forced them to flee to the province of Quebec late in the spring of 1775.

Young Claus began his military service about 1777 by enlisting as a volunteer in the King’s Royal Regiment of New York under the command of his uncle Sir John Johnson. In the summer of 1782 he apparently took part in a successful raid by Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*] against the settlements at Fort Dayton (Herkimer, N.Y.) and nearby Fort Herkimer. By war’s end, he was a lieutenant in the regiment. In October 1787 he obtained a lieutenancy in a regular British regiment, the 60th Foot, and in February 1795 was promoted captain.

As early as 1788 Sir John Johnson, who had become superintendent general of Indian affairs, had attempted to get Claus a position in the Indian Department. He recommended him for the office of deputy agent of the Six Nations in Canada, and former governor Haldimand* apparently lent his support, but Governor Lord Dorchester [Guy Carleton*] opposed the request because of Claus’s youth. In 1795, following John Campbell*’s death, Johnson tried unsuccessfully to have Claus given charge of the Indians of Lower Canada. Finally, in 1796 the death of John Butler* opened a place that Johnson was able to obtain for Claus. He was named deputy superintendent of the Six Nations at Fort George (Niagara-on-the-Lake), a position which gave him responsibility for the Indians of the Grand River, among others.

Claus reached his post in October 1796 and immediately became involved in the conflict between Joseph Brant and the government over Brant’s claim that the Six Nations of the Grand River had the right to sell off portions of their lands as they chose. Claus argued the government’s case: that the Indians did not have full sovereignty over unceded land and that under the Royal Proclamation of 1763 the sale of Indian lands could be made only through the crown. Brant continued to press the matter with Upper Canadian authorities and in 1797 he forced Administrator Peter Russell* to recognize the validity of sales that had already been arranged. Claus was named one of the trustees to manage the proceeds for the Indians’ benefit.

On 30 Sept. 1800 Claus took another step up in the Indian Department when he was appointed to succeed Alexander McKee* as deputy superintendent general for Upper Canada, a post he would hold until his death. He again found himself in conflict with Brant, who had not given up the idea of the Six Nations’ right to sell land and who in 1803 decided to go over the heads of the provincial authorities. Brant entrusted war chief John Norton with attempting to obtain the agreement of the British government itself. Claus managed to get together a council (including, said Brant, a number of chiefs from the American side of the Niagara River) that disputed Norton’s authority and claimed to have deposed Brant. Claus had a copy of the proceedings sent to London and thereby thwarted the mission.

The frontier with the United States was rather quiet during the early years of Claus’s term, but the Chesapeake affair of 1807 [see Sir George Cranfield Berkeley*] brought fears of an American invasion and authorities encouraged resuscitation of the British-Indian alliance. Claus assembled Indian chiefs at key centres such as Fort George and Amherstburg to “consult privately” with them and to remind them of the “Artful and Clandestine manner in which the Americans [had] obtained possession of their lands.” The policy was so successful that the tribes of the American northwest were too eager to engage the enemy and Lieutenant Governor Francis Gore* had to urge Claus to restrain them.

The United States finally declared war on Britain in June 1812, and throughout the conflict Claus performed his duties with efficiency and dignity. He had been appointed lieutenant of the county of Oxford in June 1802 and since then had been involved in militia matters. He was named colonel of the 1st Lincoln Militia in June 1812 and in July he was given command of British regulars and Upper Canadian militia at Fort George and Queenston Heights. Much of his time was devoted to stemming desertion. As well, he continually met in council with the Indians. In late May 1813 the Americans launched a major amphibious attack against Fort George. After a stout resistance, the defenders retreated towards Burlington Heights (Hamilton). Claus was said to have been the last officer to abandon the damaged fort, and he was with the forces that returned to it in December when the Americans withdrew.

By 1814 the toughest fight remaining for Claus was the continuation of his acrimonious feud with John Norton. Through his activities in the war, especially at the battle of Queenston Heights, Norton had gained favour with senior British authorities. In October 1813 a general order had been issued instructing the Indian Department to cooperate with any “Chief of Renown,” such as Norton, who enjoyed the Indians’ confidence. Then, in March 1814, Norton was given authority to dispense presents to the warriors fighting with him. Claus struggled to maintain the Indian Department’s prerogatives, and much bitter correspondence ensued. The conclusion of the war and the subsequent pensioning-off of Norton diminished the scope for this rivalry, and by the early 1820s the young John Brant [Tekarihogen] replaced Norton as a principal spokesman for the Grand River Indians.

For Claus and the department, the post-war years were marked by a dramatic shift in British policy towards the native people of Upper Canada. In the new era of peace, the unhindered development of the province was urgently desired, and plans were put forward which would change the Indians from warriors to wards. Key elements in the strategy were the extinguishment of Indian land title and the location of Indians in specified villages or reserves. The first post-war decade witnessed seven major land cessions by the Ojibwas of Upper Canada, and Claus played a major role in negotiating them all. An agreement made at York (Toronto) with the Mississauga Ojibwas in February 1820 was typical, concluding with the assurance by Claus that “the whole proceeds of the surrenders . . . shall be applied towards educating your Children and instructing yourselves in the principles of the Christian religion” and that “a certain portion of the said Tract – will be set apart for your accommodation and that of your families, on which Huts will be erected as soon as possible.”

As a result of the new non-military role of the Indian Department, Claus was obliged to spend much time in assisting the Indians to adapt to a new way of life and in attempting to obtain adequate funding for services the department supplied to them. He was precise and orderly; his determination sometimes caused him to clash with his superiors and at one point he was threatened with dismissal. He seems genuinely to have cared about the native people. “I trust in the end the Indians will not lose,” he wrote to George Ironside, “for I have trust in His Majesty’s kind feelings and consideration for such faithful poor people.”

Claus undertook a number of other responsibilities in addition to his work for the Indian Department. In 1812 he had been appointed to the Legislative Council, and after becoming an honorary member of the prestigious Executive Council in 1816 was made a full member in 1818. In 1816 he had been named, along with Thomas Clark and others, to the commission that negotiated with Lower Canadian representatives about the division between the two provinces of the revenue from customs duties. He had been a justice of the peace since 1803. He was also a trustee for the Niagara public school and a commissioner of customs for the Niagara District.

Claus was a proud family man, and home life was important to him. His vegetable and flower gardens were among the best in the region and his orchards were renowned. Indeed, his meticulous records provide excellent information on horticulture in Upper Canada. After suffering from cancer of the lip for about five years, he died on 11 Nov. 1826 and was buried at Butler’s Burying Ground outside the town.

PAC, MG 19, F1; RG 8, I(C ser.), esp. vols.1203 1/2–3 1/2AA, 1700–3; RG 10, A2, 11–21; 10017–18. PRO, CO 42, esp. 42/136, 42/143, 42/321. “Anticipation of the War of 1812,” PAC Report, 1896: 24–75. “Campaigns of 1812–14: contemporary narratives by Captain W. H. Merritt, Colonel William Claus, Lieut.-Colonel Matthew Elliott and Captain John Norton,” ed. E. [A.] Cruikshank, Niagara Hist. Soc., [Pub.], no.9 (1902): 3–20. “Indian lands on the Grand River,” PAC Report, 1896: 1–23. Mich. Pioneer Coll., 20 (1892). Norton, Journal (Klinck and Talman). Valley of Six Nations (Johnston). “State papers,” PAC Report, 1890: 207, 219. “State papers – U.C.,” PAC Report, 1891: 105, 115, 136, 158, 181. M. W. Hamilton, Sir William Johnson, colonial American, 1715–1763 (Port Washington, N.Y., and London, 1976). R. J. Surtees, “Indian land cessions in Upper Canada, 1815–1830,” As long as the sun shines and water flows: a reader in Canadian native studies, ed. I. A. L. Getty and A. S. Lussier (Vancouver, 1983), 65–84. Isabel Thompson Kelsay, Joseph Brant, 1743–1807: man of two worlds (Syracuse, N.Y., 1984). Allen, “British Indian Dept.,” Canadian Hist. Sites, no.14: 5–125. E. A. Cruikshank, “The King’s Royal Regiment of New York,” OH, 27 (1931): 320. Reginald Horsman, “British Indian policy in the northwest, 1807–1812,” Mississippi Valley Hist. Rev. (Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and Lincoln, Nebr.), 45 (1958–59): 51–66. C. M. Johnston, “Joseph Brant, the Grand River lands and the northwest crisis,” and “William Claus and John Norton: a struggle for power in old Ontario,” OH, 55 (1963): 267–82, and 57 (1965): 101–8. J. McE. Murray, “John Norton,” OH, 37 (1945): 7–16. G. F. G. Stanley, “The significance of the Six Nations participation in the War of 1812,” OH, 55 (1963): 215–31.

Cite This Article

Robert S. Allen, “CLAUS, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 27, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/claus_william_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/claus_william_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert S. Allen |

| Title of Article: | CLAUS, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | January 27, 2026 |