Source: Link

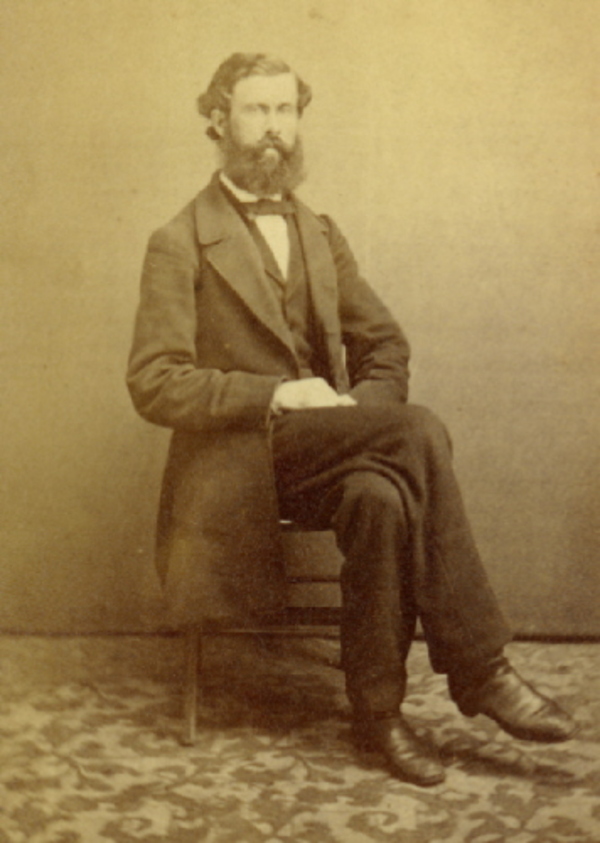

CUNDALL, HENRY JONES, land surveyor, estate agent, and philanthropist; b. 13 Jan. 1833 in New London, P.E.I., eldest child and only son of William Cundall and Sarah Louisa Haszard; d. unmarried 16 July 1916 in Charlottetown.

Henry Cundall was born into a family of considerable distinction, if not exceptional wealth. His father had migrated from England to Prince Edward Island in 1828 to manage the family’s extensive landholdings and, failing to garner enough income from his properties, became a businessman in Charlottetown and later headmaster of Central Academy there. In 1856 he was appointed cashier (general manager) of the Bank of Prince Edward Island. Henry’s mother came from a prominent Island loyalist family.

Family circumstances ensured that Henry received a good general education, at Central Academy, but also training in a vocation. After studying surveying with an uncle, he began work at about age 16 in the Charlottetown office of Samuel* and Edward Cunard, who were important estate owners on the Island, and by 1853 he had become surveyor for the Cunards. In a separate venture in 1851 Cundall completed a map of the colony, a cartographic achievement that won recognition as a benchmark of accuracy. He had opened his own office by 1863 and by 1868 he was an established surveyor and property agent, undertaking among other commissions survey work for the Prince Edward Island Railway. He would later become a member of the provincial board of examiners for land surveyors. In addition to being a skilled surveyor, he earned a reputation as a careful and adept money manager and, following the expropriation of the large landed estates in 1875 [see Lemuel Cambridge Owen], he acted as a trustee for former owners wishing to invest their indemnities. Cundall himself invested in his father’s bank, the local gas company, and safe loans, and he was president of the Telephone Company of Prince Edward Island from 1894 to 1901. By careful management of his capital, he became in time one of the Island’s richest men.

Cundall’s professional life was marked by competence and prudence but not flamboyance. Contemporaries recognized him as a major figure in the economic life of the community; however, he was renowned more for his involvement with a wide range of philanthropies. Some of these were religious in nature, a manifestation of his commitment as a low-church Anglican. He joined with leading members of local Protestant churches to help found the Prince Edward Island Hospital in 1883, accepting a role as a trustee in the process, and he lent active support to an Anglican initiative of a school in Charlottetown’s poorest district, known as the Bog. An early connection with the Young Men’s Christian Association foreshadowed lengthy service as treasurer, beginning in 1863 and continuing into the 20th century. The hospital, the YMCA, his parish church, and various missionary societies were named as beneficiaries in Cundall’s will, but the largest portion of his legacy, including his substantial mansion, Beaconsfield, was dedicated to the establishment of a home for “friendless young women and girls” where “training in industrial and Christian ways” would enable them to lead useful and respectable lives.

Local politics engaged Cundall’s energies only to a limited extent. A dedicated advocate of temperance, he also participated in the campaign for a municipal waterworks in Charlottetown. He remained aloof from elected public service, however, preferring to exercise influence behind the scenes. Cundall regarded hobbies with a scientific connection to be a more fruitful use of his time. He was an observer for the Meterological Service of Canada between 1872 and 1886, and he was a pioneer amateur photographer. He had become interested in the camera by 1859 and was one of the first in British North America to use the dry-plate photographic process. Most of his subjects seem to have been people. He also acquired a magic lantern and an array of scenic slides which he used in public lectures.

Cundall led a disciplined, purposeful existence, almost an ideal expression of Victorian “muscular” spirituality. His domestic life revolved around three unmarried sisters, one of whom, regrettably in his view, adopted high-church Anglicanism and became a nun in England. A second sister died in 1888, but the third, Penelope Anne, lived until 1915 as chatelaine of Beaconsfield. There, for many years, entertainment consisted of the occasional strawberry social and more frequent musical evenings with select friends. Cundall’s personal activities ranged from hunting and fishing expeditions to vigorous walking or skating, and quiet evenings reading and making entries in a diary. While not dour, Cundall was strict with himself as well as with others. A reputation for miserliness was probably undeserved, but he was frugal with money as the young Robert Harris learned to his dismay. The “paltry remuneration” Harris received for his work in Cundall’s office was nevertheless sufficient to permit the young painter to study art in England and Boston.

A man of Henry Cundall’s stamina, ethics, and perspicacity would likely have prospered anywhere. That he chose to remain on Prince Edward Island reflects a conservatism and a deep attachment to his native community. Typical of his social peers, when he looked beyond the Island, he looked to the United Kingdom and thence to the wider empire. His worldview was not parochial, but he was aware that there was much to do and accomplish at home. He turned to these tasks quietly and effectively so that in time his influence came to be felt throughout the economic and social life of his city and province.

[Henry Jones Cundall left historians a rich legacy of manuscripts in the form of his diaries, which are found at PARO, Acc. 3466, ser.72.139, and his letter-books, Acc. 4158. A recent survey of these sources in connection with the documentation of Cundall’s home, Beaconsfield, has produced among other findings a fine article by [G.] E. MacDonald, “The master of Beaconsfield, part two: Henry J. Cundall,” Island Magazine (Charlottetown), no.34 (fall/winter 1993): 7–14. Another article, Theresa Rowat, “Island photography, 1839–1873,” Island Magazine, no.14 (fall/winter 1983): 14–21, is helpful in placing Cundall’s work as a photographer into its wider context.

A biographical sketch of Cundall by Walter C. Auld appears in his book, Voices of the Island: history of the telephone on Prince Edward Island (Halifax, 1985); it is also found in typescript at the PARO (P.E.I. Geneal. Soc. coll., reference files, Cundall-1). Cundall published a couple of his own works in the Prince Edward Island Magazine (Charlottetown), from 1904 the Prince Edward Island Magazine and Educational Outlook: “Captain Holland’s survey,” 1 (1899–1900): 250–53, and “The early days of the Young Men’s Christian Association and Literary Institute,” 6 (1904): 192–201. An anonymous article on “The Y.M.C.A.” in the Prince Edward Island Magazine, 4 (1902–3): 140–43, helps to provide some background for Cundall’s work with the association. R. C. Tuck, Gothic dreams: the life and times of a Canadian architect, William Critchlow Harris, 1854–1913 (Toronto, 1978), reveals aspects of Cundall as they touched William Critchlow Harris. The social status which Cundall attained in Charlottetown is established by D. [O.] Baldwin, “The Charlottetown political elite: control from elsewhere,” in Gaslights, epidemics and vagabond cows: Charlottetown in the Victorian era, ed. D. [O.] Baldwin and Thomas Spira (Charlottetown, 1988), 32–50. Some of Cundall’s financial activities are covered in D. O. Baldwin and Helen Gill, “The Island’s first bank,” Island Magazine, no.14 (fall/winter 1983): 8–13, and D. O. Baldwin, “The growth and decline of the Charlottetown banks, 1854–1906,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 15 (1985–86), no.2: 28–52.

Records in the P.E.I. Geneal. Soc. coll. at the PARO (reference files, Cundall-4–5) are helpful to confirm the essential dates of Henry Cundall’s life; his will, dated 26 Oct. 1904, and the probate inventory of his estate, dated 1 Aug. 1916, both in PARO, Supreme Court, estates div. records (mfm.), delineate the extent and disposition of his fortune. The Atlantic Canada Newspaper Survey database, available on-line through the Canadian Heritage Information Network administered by Communications Canada, Ottawa, includes a number of documents recording newspaper references to Cundall’s business and personal activities. Obituaries are found in the Charlottetown Guardian and the Charlottetown Patriot for 17 July 1916. p.e.r.]

Cite This Article

Peter E. Rider, “CUNDALL, HENRY JONES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 19, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cundall_henry_jones_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cundall_henry_jones_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter E. Rider |

| Title of Article: | CUNDALL, HENRY JONES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 19, 2025 |