Source: Link

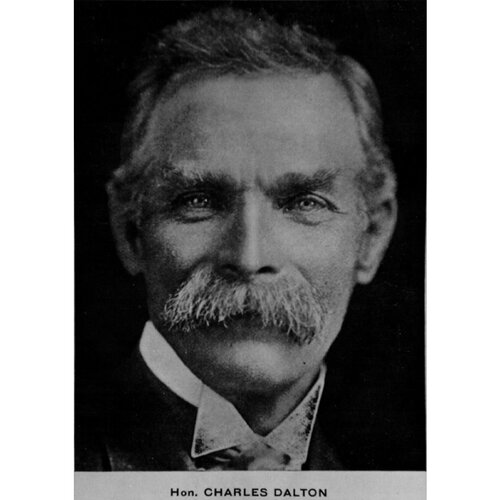

DALTON, CHARLES, farmer, druggist, co-founder of the silver-fox industry in Prince Edward Island, politician, philanthropist, and office holder; b. 9 June 1850 in Tignish, P.E.I., son of Patrick Dalton and Margaret McCarthy; m. there 30 June 1874 Annie Gavin, and they had 12 children, 5 of whom died young; d. 9 Dec. 1933 in Charlottetown.

A son of Irish Roman Catholic immigrants, Charles Dalton grew up on his family’s homestead in Norway, P.E.I., and attended the district school at neighbouring Christopher Cross. From a very young age, Dalton loved the outdoors, and he became known as an expert shot and trapper. Farming was his first occupation, but he was not particularly interested in agriculture or successful at it. The Island’s rural economy was poor in the 1880s, and Dalton sold his farm in Norway in December 1884 and then moved with his wife and children to the nearby village of Tignish. There he bought a pharmacy. Although chemistry fascinated him, the store failed within a decade.

Throughout this entire period, Dalton retained his near obsession with hunting and trapping. He was most drawn to the rare black or silver fox, a mutation of the red fox. Speaking at a dinner held in his honour in 1929, he would say, “At every opportunity I indulged in my passion for the chase and soon became an expert shot and trapper. The fox was my great objective, and the very name of ‘black fox’ had a romantic attraction for me beyond any other allurements of sport.”

Dalton had begun trying to raise silver foxes in captivity during the 1880s. He entered into a partnership in 1894 with Robert Trenholm Oulton*, a hunting and fishing acquaintance, for the purpose of breeding foxes. This arrangement probably began more as a means to pursue a hobby than to establish a business, but it soon became a lucrative venture. The two men dealt with different aspects of the operation. Although both had a great deal of experience in hunting and trapping, it was Oulton who took on the daily care of the animals. Dalton, who supplied the initial breeding stock, handled the finances and marketing.

Breeding foxes in captivity had been attempted by others, but the operation run by Dalton and Oulton was the first to achieve long-standing success. With hexagonal wiring obtained in Montreal, they built a pen on Oulton’s secluded Cherry (Oultons) Island farm, near Alberton. After three animals escaped, the partners modified the pen’s design. They worked towards an attractive strain of silver or black foxes by mating silvers. Silver pups were not guaranteed, but as the breeding experiments continued, the desired results were obtained more and more frequently. Using the same foundation stock, each man developed a herd that had distinctive qualities. The pelts of Dalton’s foxes were thick and dark except for a white tip on the tail, while those grown by Oulton’s animals tended to be bluish-black. Dalton would set up his own ranch at Tignish in 1897, but he maintained his professional association with Oulton.

The two were determined to keep their work secret and establish a monopoly. Intending to retain their finest stock for breeding, they wanted and needed to sell some of their second-class pelts. The annual January fur sale at C. M. Lampson and Company in London provided the necessary market, and the pair shipped the furs out of a small harbour at night to maintain secrecy. In 1900 they received $1,807 for a single pelt.

Dalton and Oulton had not found it possible to keep their activities entirely concealed, and by the late 1890s others had become interested in the business. In 1900 the partnership was expanded into the Big Six Combine with the addition of neighbours Silas Rayner, Benjamin I. Rayner, Robert Tuplin, and James Gordon. The group had an unwritten agreement that no live foxes were to be sold. Their pact enabled a controlled growth of the industry and ensured that principles of high quality, reinvestment, and loyalty were practised. Of the 20 fox ranches operating in North America in 1909, 12 were in the Tignish–Alberton area. The monopoly of the Big Six was broken in 1910 when Robert Tuplin’s nephew, Frank F. Tuplin, sold two pairs of live silver foxes for $10,000. During the fox boom of 1910–14, fortunes were made and lost. In 1910 Dalton sold 25 pelts in London for more than $20,000, at a time when an Island farm worker could expect an annual wage of $320. The commissioner of agriculture would report in 1914 that the 3,130 foxes being raised on the Island’s 277 ranches in the previous year had a value of $14 million.

In 1911 Robert Oulton moved to Little Shemogue, N.B., and the following year he and Dalton amicably ended their partnership. Dalton sold his Tignish ranch and set up a new operation in Southport, near Charlottetown, in 1913. The move corresponded with Dalton’s involvement in a public company, the Charles Dalton Silver Black Fox Company Limited, for which he had been paid $400,000 and had received $100,000 in shares in 1912. The breeding of high-quality silver foxes decreased markedly on Dalton’s Southport farm, and the industry was also hurt overall by the declaration of war in 1914. That year Dalton sold all his fox holdings, later stating that he “foresaw what was coming.”

Upon his retirement from active farming, he devoted more time to a career in provincial politics. He had run unsuccessfully in the election of 1908, but was returned as a Conservative member of the Legislative Assembly in both 1912 and 1915. He represented Prince County, 1st District, which included Tignish, and from 1915 served as a minister without portfolio under premiers John Alexander Mathieson* and Aubin-Edmond Arsenault*. Dalton retired from politics after failing to gain re-election in 1919.

His success in business enabled him to focus on charitable service and philanthropy as well as his political career. Dalton was the greatest benefactor of the province’s health and educational institutions during the 20 years before his death in 1933. One of his most generous and best-known gifts was a tuberculosis sanitarium, which ultimately cost him at least $60,000. One of Dalton’s daughters had died in 1906 of tuberculosis, a major killer in the early part of the century. The sanitarium, the first in the province, opened in the summer of 1916 at North Wiltshire, near Charlottetown. Dalton bought the land and built the facility, which was designed to accommodate 24 beds and was fully equipped. It was a much-needed institution but became caught up in disputes over funding. According to the 1913 act that had provided for the sanitarium’s establishment, the province was meant to pay the operating costs. In 1916, however, the government passed on the expense to the federal Military Hospitals Commission, which enlarged the sanitarium and used it as a convalescent home for veterans, many of them tubercular. In 1920 the facility was returned to the province. But the Liberal government of John Howatt Bell* refused to accept responsibility for it and in 1922 gave it back to Dalton, although the Island had the highest rate of mortality from tuberculosis in Canada. A newspaper article noted, “It would not be too much to say that in the whole Dominion of Canada if indeed anywhere in the world a similar instance of ingratitude or political animus could [not] be found.” The government denied Dalton the right to sue to recover his investment. He allowed the equipment and materials to be used in the reconstruction of Charlottetown Hospital, and his gift was soon an empty ruin. Prince Edward Island became the only province in the 1920s without a tuberculosis sanitarium.

Besides giving generously to the cause of public health, Dalton made notable contributions to education. He had a personal interest in St Dunstan’s College, a Catholic school that achieved university status in 1917. His sons Charles Howard and Joseph Gerald graduated from the institution in 1896 and 1920 respectively. The school suffered ongoing financial problems, partly because most of its students were local and the Island was cash-poor, so many tuition fees were in arrears. In 1913 Father Francis Clement Kelley, an Islander who was founder and president of the Catholic Church Extension Society in the United States, asked Dalton for $50,000 to construct a missionary college at St Dunstan’s. He pleaded, “If you can do this, it would be the biggest thing that any man has yet done in Canada sofaras practical results, for God and Religion are concerned.” Dalton agreed to guarantee $5,000 a year for a decade. He joined St Dunstan’s board of governors in July 1914, and construction of Dalton Hall, a residence rather than a missionary college, was begun in 1917. The building was opened in 1919, although it was still unfinished. In 1916 he had been made knight commander of the Order of St Gregory the Great, a papal honour awarded for his “generous benefaction towards education and his charity for suffering humanity.”

Dalton made many other contributions to his province. In 1916 he provided a field ambulance for war service, at a cost of $2,100. He served as a trustee of the estate of Owen Connolly, another self-made Island millionaire of Irish extraction, who left a sum to be put towards the education of poor children of Irish ancestry. A donation of several thousand dollars went to the reconstruction of St Dunstan’s Cathedral, which was completed in 1919. Dalton School was built in the parish of Tignish in 1930 with its namesake’s gift of $20,000.

After the end of World War I, Dalton and his family had moved to Brookline, Mass. Islanders had many connections with the Boston area, the most common destination for the thousands who left the province between the 1870s and the 1930s. Dalton often travelled back to the Island, especially to a nature sanctuary he owned at Nail Pond. His family, however, remained in the Boston area.

In 1930, at the age of 80 and despite his residence in the United States, Dalton was appointed lieutenant governor of Prince Edward Island. He participated fully in the duties of the position until his death in December 1933, caused by a fall on ice and the effects of pneumonia. He received a full state funeral, held at St Dunstan’s and presided over by Joseph Anthony O’Sullivan, bishop of Charlottetown. He was buried in Tignish.

Alberton Museum (P.E.I.), “Lieut Gov Dalton of P.E.I. is dead: former Brookline resident pneumonia victim” (unknown newspaper clipping, [Boston]), 10 Dec. 1933. International Fox Museum and Hall of Fame Inc. (Summerside, P.E.I.), Wayne Wright, “B. I. Rayner Exhibit.” LAC, RG 31, C1, 1891, Tignish, P.E.I., Lot 1-B1 (mfm. at PARO); 1901, Prince County (West), P.E.I., A-2: 14. PARO, Acc. 2671, box 29; Acc. 2860, item 8, 1914; item 9, 1975 (photocopy); Acc. 3034/1; Acc. 3322; Fonds C101, 30 June 1874; RG 16, liber 13, f.539; RG 34, ser.6, file 2. Private arch., Heidi MacDonald, Interview with Gerald Handrahan, Christopher Cross, P.E.I., 14 Aug. 1989. Tignish Cultural Centre, J. H. Gaudet, “Genealogical records, Sir Charles Dalton and Annie Gavin.” Univ. of P.E.I., Robertson Library, Univ. Arch. & Special Coll., P.E.I. Coll. (Charlottetown), R. A. Rankin, “A biographical sketch of Sir Charles Dalton – foxman.” Charlottetown Guardian, 10 March, 19 April, 11 Aug. 1916; 13 July 1929; 11 Dec. 1933. Island Patriot, 10 March 1916. H. J. Champion, Over on the island (Toronto, 1939). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.3. J. E. and A. D. Forester, Silver fox odyssey: history of the Canadian silver fox industry (Charlottetown, [1980?]). Paul Gunn, “The silver fox industry on Prince Edward Island” (ba thesis, Mount Allison Univ., Sackville, N.B., 1973; copy in the Univ. of P.E.I., P.E.I. Coll.). Helen Lanigan and Boyde Beck, “The great white plague: tuberculosis on Prince Edward Island, 1888–1931,” Island Magazine (Charlottetown), no.57 (spring/summer 2005): 22–29. G. E. MacDonald, The history of St. Dunstan’s University, 1855–1956 (Charlottetown, 1989); If you’re stronghearted: Prince Edward Island in the twentieth century (Charlottetown, 2000). Katherine McCuaig, The weariness, the fever and the fret: the campaign against tuberculosis in Canada, 1900–1950 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1999). Minding the house (Weeks). Tom O’Connor, “Descendants of John McCarthy”: www.islandregister.com/dalton.html (consulted 29 Oct. 2012). Office of the Lieutenant Governor, “The Honourable Charles Dalton”: www.gov.pe.ca/olg/gallery/picture_setup.php?lg=26Dalton (consulted 29 Oct. 2012). R. A. Rankin, “Fox farming on Prince Edward Island,” in Exploring Island history: a guide to the historical resources of Prince Edward Island, ed. Harry Baglole (Belfast, P.E.I., 1977), 165–74; “Robert T. Oulton and the golden pelt,” Island Magazine, no.3 (fall/winter 1977): 17–22. St Dunstan’s Univ., Alumni Assoc., Centennial booklet and directory of all students registered since January 17, 1885 ([Charlottetown], 1954; copy in Univ. of P.E.I., P.E.I. Coll.). “75 Queen Street, Connolly Block”: www.gov.pe.ca/hpo/app.php?nav=details&p=4230 (consulted 29 Oct. 2012). P. A. Thornton, “The problem of out-migration from Atlantic Canada, 1871–1921: a new look,” in Atlantic Canada after confederation: the Acadiensis reader, volume 2, ed. P. A. Buckner and David Frank (2nd ed., Fredericton, 1988), 34–65. G. J. Wherrett, The miracle of the empty beds: a history of tuberculosis in Canada (Toronto, 1977).

Cite This Article

Heidi MacDonald, “DALTON, CHARLES (1850-1933),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dalton_charles_1850_1933_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dalton_charles_1850_1933_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Heidi MacDonald |

| Title of Article: | DALTON, CHARLES (1850-1933) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2014 |

| Year of revision: | 2014 |

| Access Date: | February 9, 2026 |