Source: Link

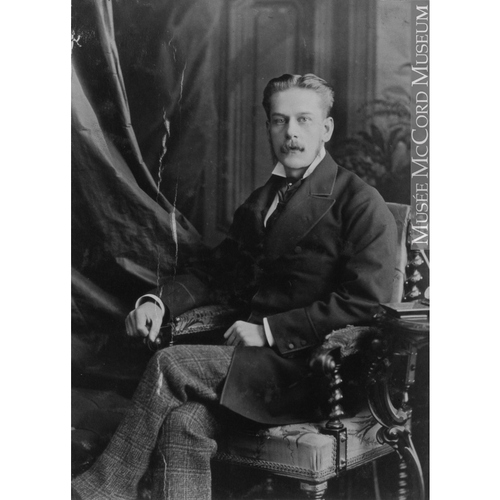

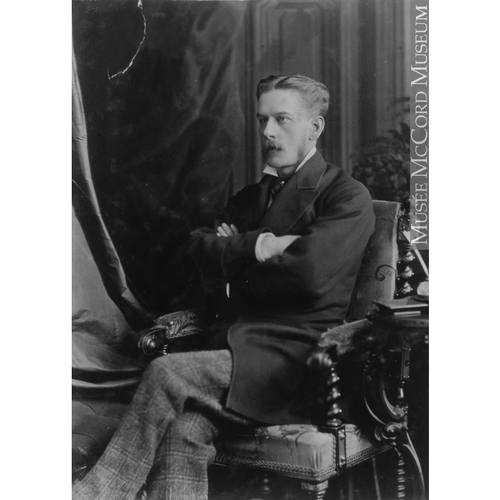

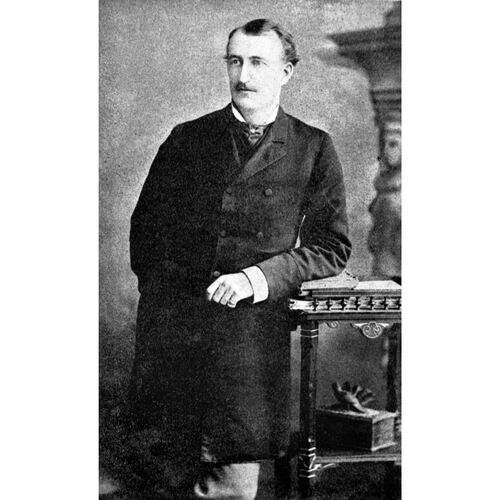

GAGE, Sir WILLIAM JAMES, teacher, businessman, and philanthropist; b. 16 Sept. 1849 in Toronto Township, Upper Canada, son of Andrew Albert Gage and Mary Jane Grafton; m. 4 May 1880 Ina (Imey) Burnside in Toronto, and they had five daughters, one of whom died in infancy; d. there 14 Jan. 1921.

The youngest of seven children, William J. Gage was born on a farm south of Brampton. His father was originally from Stoney Creek; his mother, a native of South Carolina, had come to Upper Canada in 1812. Educated in Derry West and at the Brampton grammar school, he received his teaching certificate from the Toronto Normal School in 1866 and taught for three years in Broddytown (Brampton) before entering the Toronto School of Medicine. Though he could not tolerate the gruesome aspects of the operating theatre and left the school after a year, he would later channel his time and riches into the field of health.

Gage subsequently focused his passion for efficiency, his energy, and his Methodist ideals on commerce and charity. In 1871 he embarked on his first venture, buying and selling cordwood in Brampton. He then became a bookkeeper with a Toronto publisher, Adam Miller and Company. After Miller’s death in 1875, he continued as a partner in the firm, which he took over in 1879 and renamed W. J. Gage and Company. Although the market for textbooks, its most important line, was rife with competition, governmental intrusion, and copyright disputes, Gage achieved considerable success. In 1893 his company was incorporated. A promotional booklet later claimed that “there is . . . not a community throughout the Dominion where the schoolbooks published by this house have not found a place.”

After fire destroyed Gage’s building on Front Street in 1904, he immediately constructed a five-storey factory on Spadina Avenue, “laid out to handle the business in the most systematic and economic way possible.” His integrated operation included a paper plant in St Catharines, sophisticated Miehle presses for colour printing, and the sale of writing paper and envelopes in addition to textbooks. An imposing figure, he presided over a richly decorated office that reflected his thoroughness and attention to detail, qualities also evident in his private life. He was an affectionate but at times controlling husband whose letters to his wife, during his travels on business, frequently reprimanded her for not writing more often.

In 1893, with some wealth at his disposal, Gage had turned his attention to tuberculosis, Canada’s most lethal disease. He committed himself to the sanatorium movement – drug treatment would not become available until the 1940s – and investigated sanatoria in Europe and the United States. His offer in 1894 to fund a hospital in Toronto had the backing of the Board of Trade, whose president, Hugh Blain, had encouraged Gage to tackle tuberculosis, but city council hesitated. “No . . . delightful reward awaited the man who tried to start sanatoria, especially in the early years of the movement,” Gage would recall. Some critics even sent him threatening letters. Publicly regarded as incurable and contagious, tuberculosis was popularly associated with indigence, squalor, overcrowding, and unhygienic living habits. Gage remained undaunted, however, and in 1895 Hart Almerrin Massey* and other influential citizens threw their weight behind his efforts.

In 1896 Gage helped found the National Sanitarium Association and two years later the Toronto Citizens’ Sanatorium Committee, which led to the creation in 1900 of the Toronto Association for the Prevention and Treatment of Consumption and Other Forms of Tuberculosis. Between 1897 and 1913 he established several treatment facilities: the Muskoka Cottage Sanatorium and the Muskoka Free Hospital for Consumptives near Gravenhurst; the Toronto Free Hospital for Consumptives, the King Edward Sanatorium for Consumptives, and the Queen Mary Hospital for Children, all near Weston (Toronto); and a free dispensary in Toronto. In 1912 he initiated the King Edward Memorial Fund for Consumptives. The following year, in recognition of his work, he was made a knight of grace of the Order of St John of Jerusalem in England.

Gage also used his money to promote his political and religious values. In 1893 he had headed a group who purchased the Toronto Evening Star to fight the provincial Liberal government, which, by taking control of the copyrights on many textbooks, had undermined Gage’s near-monopoly. He also wanted a vehicle for defending the local ban on streetcar service on the sabbath. As chairman of the Citizens’ Anti-Sunday Car Association, he challenged Mayor Warring Kennedy to resist mounting pressure for Sunday service, which the Star saw as a sign of “degenerate days.” Gage’s campaigns ended in 1895 when the newspaper was bought by Edmund Ernest Sheppard, fronting for Frederic Thomas Nicholls and the Toronto Street Railway.

The streetcar commotion, which concluded in 1897 with the authorization of Sunday service, was not the end of Gage’s civic involvement. He was active in the Board of Trade, and was a delegate in 1909 to the Congress of Chambers of Commerce of the Empire, where he argued that the colonies should have their own laws on copyright. Elected president of the board the following year, he pushed for the development of the city’s waterfront, a board of harbour commissioners, and improved highways between Toronto and York County. “We should plan for a city of a million people,” he reasoned in January 1910. In November he took the lead in forming the Ontario Associated Boards of Trade and became its first president.

During the war years Gage’s sanatoria interests remained strong. At a cost of more than $100,000, he funded the construction of the National Sanitarium Association’s new headquarters and dispensary (the Gage Institute), which opened on 10 Feb. 1915. The following year he helped negotiate the admission of tubercular soldiers to the Muskoka sanatorium, demonstrating in the process his autocratic style and skill in driving hard bargains. In 1917 Gage and his wife set aside $110,000 for the Ina Grafton Homes Corporation, to provide rental accommodation for war widows and orphans. He was granted an honorary lld that year by Mount Allison College in Sackville, N.B., and in 1918 he was made a knight bachelor.

Gage was much sought after for the boards of other charities and businesses. He chaired the Toronto branch of the Victorian Order of Nurses, and was a director of the Imperial Bank of Canada, the Traders’ Bank of Canada, the Ontario Sugar Company, and the Anglo-American Fire Insurance Company. Devastated by the burning of the Muskoka Free Hospital on New Year’s Eve 1920, he suffered a stroke and died at his Wychwood Park estate. His church, Trinity Methodist, held two services in his honour. The Toronto Daily Star stated that Gage had “combined a kindly and understanding mind with great fixity and tenacity of purpose.” He represented a generation of businessmen who put profit-making in the service of humanitarianism to achieve their concept of a better society.

AO, F 1193-A-3, box 24, folder 141; RG 22-305, no.42995; RG 80-5-0-95, no.13255. Private arch., Mrs Diana Gage Griffith Tisdall (Toronto), Gage family papers. TRL, SC, Biog. files, vols.2–3, 6. Toronto Daily Star, 8 Jan., 8, 11 March, 10, 18 June, 16 July, 2 Oct. 1894; 5, 8, 14–15 Jan. 1921. G. C. Brink, Across the years: tuberculosis in Ontario ([Willowdale (Toronto), 1965]). Canadian annual rev., 1901–21. Canadian Assoc. for the Prevention of Tuberculosis, Annual report (Ottawa), 1901–21. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Construction (Toronto), 11 (1918): 168–74. Dict. of Toronto printers (Hulse). Dominion annual reg., 1883. G. L. Gale, The changing years: the story of Toronto Hospital and the fight against tuberculosis (Toronto, 1979). Ross Harkness, J. E. Atkinson of the “Star” (Toronto, 1963). Gerald Killan, David Boyle: from artisan to archaeologist (Toronto, 1983). Desmond Morton and Glenn Wright, Winning the second battle: Canadian veterans and the return to civilian life, 1915–1930 (Toronto, 1987). G. L. Parker, The beginnings of the book trade in Canada (Toronto, 1985). The province of Ontario: a history, 1615–1927, ed. J. E. Middleton and Fred Landon (5v., Toronto, 1927–[28]), 5: 789–91. Victor Ross and A. St L. Trigge, A history of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, with an account of the other banks which now form part of its organization (3v., Toronto, 1920–34), 3. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). G. H. Stanford, To serve the community: the story of Toronto’s Board of Trade (Toronto, 1974). W. J. Gage and Company, Manufactured stationery, 1909–1910: catalogue no.1 (Toronto, [1909]); Educational works & school blanks: catalogue no.4, 1911–1912 (Toronto, [1911]); copies in TRL, SC). G. J. Wherrett, The miracle of the empty beds: a history of tuberculosis in Canada (Toronto, 1977). Who’s who and why, 1921.

Cite This Article

Molly Pulver Ungar and Vicky Bach, “GAGE, Sir WILLIAM JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gage_william_james_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gage_william_james_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Molly Pulver Ungar and Vicky Bach |

| Title of Article: | GAGE, Sir WILLIAM JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |