Source: Link

GLODE, JAMES, Micmac (Mi’kmaw) hunter and guide; b. or baptized 25 July 1831 at Lake Kejimkujik, N.S., son of Francis Glode and Madeline Knockwood; he had 2 wives, one of whom was named Mary ———, and 26 children; d. 29 Feb. 1936 in Shubenacadie, N.S.

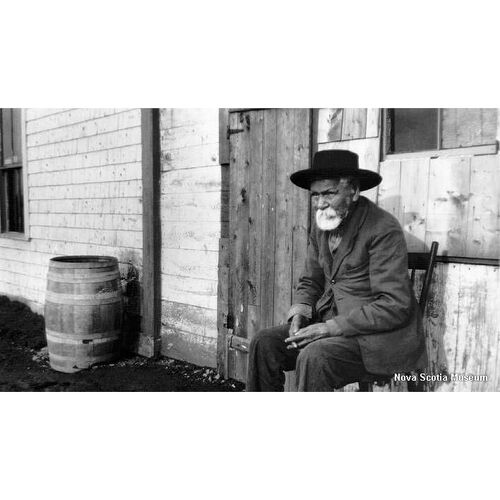

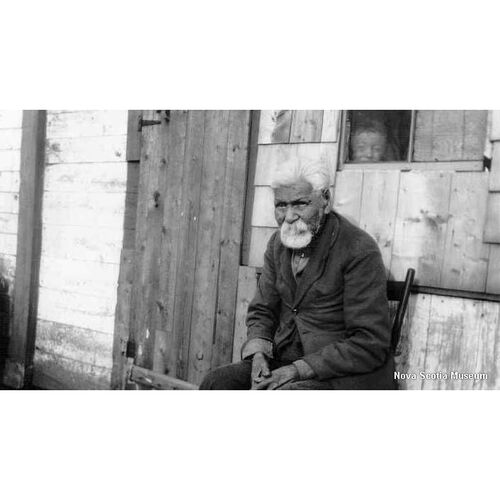

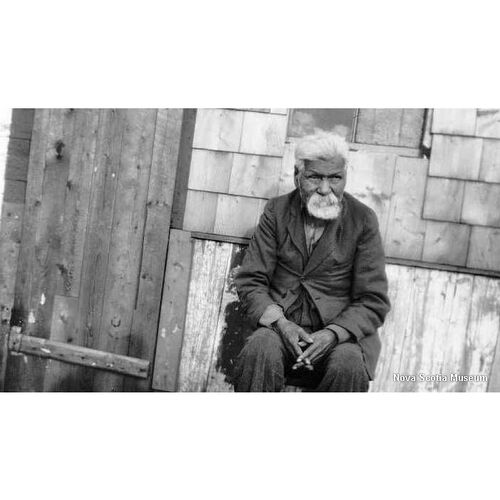

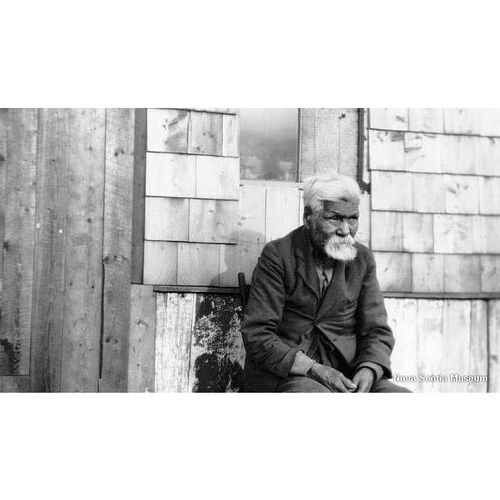

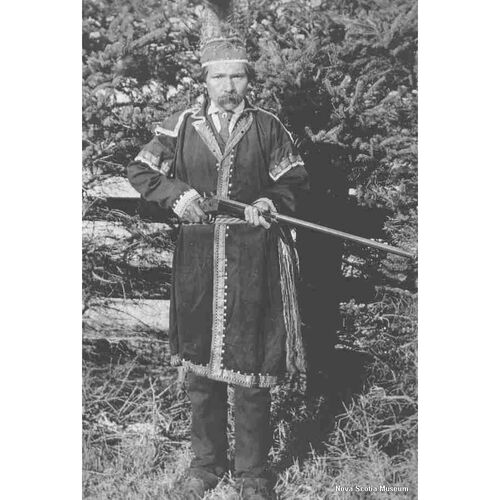

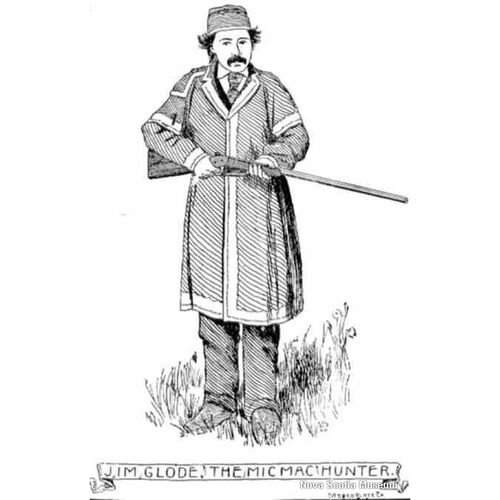

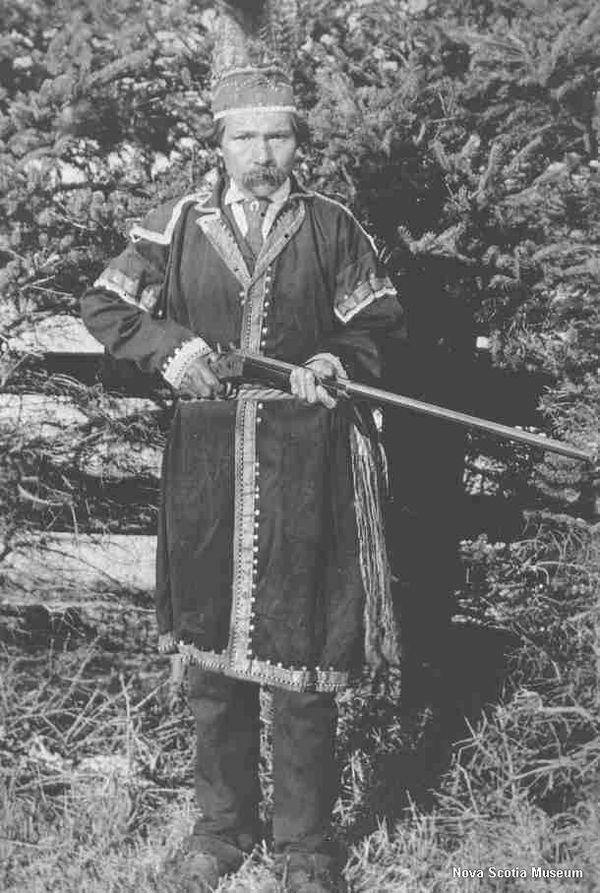

In the early 1890s a photographer was at the Shubenacadie Reserve in Nova Scotia, probably on St Anne’s Day, traditionally an occasion among the Micmac (Mi’kmaq) for religious rituals and social interaction. Besides taking a group picture, the visitor shot a portrait of a single individual: James Glode, whose fame as a guide and hunter made him a man of note.

Clarissa (Clara) Archibald Dennis, a reporter for the Halifax Herald, began interviewing and photographing Jim Glode in the late 1920s. On one visit he said that he was “age 98 today July 26 1929.” He told her, “My Grandfather Joe Glode, French from Liverpool, N.S. French Acadian. Father Francis Glode.” He was perhaps a descendant of the chief called Old Claude (Glaude Gisigash), who, describing himself as “Governor of LaHave,” made peace with the colonial authorities in Halifax in 1753, receiving the same terms as Jean-Baptiste Cope* during the Anglo-Micmac hostilities that ended in 1761 [see Pierre Maillard*]. Glode said that his father, Francis, had been a “great prophet,” and it seems that the Micmac believed he had foreseen the creation of the radio. Dennis noted that Glode had been married twice and had had ten children with his first wife, but only two were then living: his son, Peter, and a daughter. He had had 16 children with his second wife.

Glode was one of the guides who took Prince Arthur*, later governor general of Canada, hunting in Nova Scotia in 1869. (It was recorded that “they got nothing.”) He told Dennis of his experiences when he was hired first as a camp attendant and then as a guide by a group of avid sportsmen who came in the summers to Canada “for thirty years, in order to spend six months hunting.” It seems that, one year, they went to South America together. There were four English gentlemen in the party, “three brothers & another high fellow.” Harry Piers, curator of the Provincial Museum of Nova Scotia, identified three of the sportsmen as the sons of James Du Pre Alexander, 3rd Earl of Caledon: James, the 4th earl, and his brothers, the Honourable Walter Philip and the Honourable Charles. They were accompanied by their friend Charles Stayner. Glode went with them to the Rocky Mountains in British Columbia and to Montana. He said he had killed buffalo, grizzly bears, and mountain lions on both sides of the border.

Glode was living in Shubenacadie in 1855, according to the list made for the provincial commissioner of Indian affairs. At another stage in his life he resided at Bear River. When he was middle-aged, he stayed for a period with the family of Isaac Sack, chief of the Shubenacadie Reserve. He often told stories of his exploits to Sack’s grandchildren. In doing so, he passed on eyewitness accounts of history from the native perspective in a part of the North American continent far removed from the scene of the events he described. In 1976 two members of his audience, Max and Isaac Basque, related the dramatic tale of an occurrence that had taken place during a trip that Glode had made, probably with Charles Alexander, about a century earlier, during the years of hostility between whites and the Sioux in the Dakota Territory.

They were out on the Plains, and for days they hadn’t seen any buffalo. One day the scouts came in and said that they was pressing their ears to the ground, they could hear hooves, but they weren’t sure whether these hooves was buffalo or horses. After a while they could tell that these was horses, and that they weren’t shod. There were many of them, coming fast. Now this was around the time when the Plains Indians weren’t getting on so well with the U.S. Cavalry, so the [English] lord told Jim Glode to get out the British Ensign, and fly it, so they would not be taken for Americans. About half an hour later, over a little rise comes Sitting Bull [Ta-tanka I-yotank*] and Crazy Horse and about a thousand Sioux warriors.

“We haven’t eaten for four days,” says Crazy Horse, “and we can’t afford to kill any more horses. So we must take some of your supplies and some of your horses. But we will only take half.” So they thanked them.

A few weeks later, still hunting buffalo, they [Glode’s party] came on a bunch of cavalry, cleaning their guns and things after a famous victory. The Englishman got invited in the tent to take a drink, with the Colonel in his tent. After they was riding away, he said to Jim, “Jim, you notice anything funny about them men?”

“Yes,” said Jim. “None of them were wounded.”

“Let’s backtrail and look at the site of this … where this battle was.”

So for some days they was riding, until they came to a burnt camp, ruined camp. Dead in the grass was where they found the losers. All the old men, all the women and their children, see. Because all the young men were out with Crazy Horse. He … Jim Glode, he always began to cry while he was telling us how he turned over this young woman and about finding a dead baby in her arms. A sword going in from behind had killed both of them; the mother was running away from the soldiers.

After they buried the bodies, the Sioux interpreter with Glode’s party left to find Crazy Horse. When he rejoined the hunting party in Canada some time later, he told Glode about the battle of the Little Bighorn River, and he in turn described it to the Basques. The interpreter’s account is different from other descriptions of the conflict. He said that Sitting Bull had told some young Sioux to lure the army into a valley.

Then Crazy Horse hid us all [the other Sioux] in the sagebrush. He said, “Wait. Wait. When they come in, don’t shoot the men. Shoot the horses.… And then we shoot the men.” After a while, we could hear the young men riding back down into the valley. Only about ten of them made it back. And we were spread out almost in a ring. When the cavalry came down in after them, we closed that ring. We began to kill the horses. And then we killed them all.

Another story told by Max Basque (in 1987) described one of Glode’s experiences in Oregon. He saw several drunken cowboys shoot three Chinese men who were sitting on a log by the side of the road. The victims fell backwards, where they remained all day, ignored by the townsfolk. After witnessing this murder, Glode decided that it was time to return to Nova Scotia.

He apparently retained his knowledge and skills during his later years. In 1924 Glode was named by Jerry Lonecloud* as one of the few Micmac who still knew how to make a birchbark canoe. In 1929, when he was almost a century old, he was living with his son Peter and his family on the Shubenacadie Reserve. Peter’s wife told Clara Dennis, “That old man never sick all winter, don’t bother with rheumatiz or anything, good appetite, good voice, not hard of hearing very much, only getting blind.” Dennis’s notes add the following information about Glode: “Can’t read or write but said he could count. Could talk in English.”

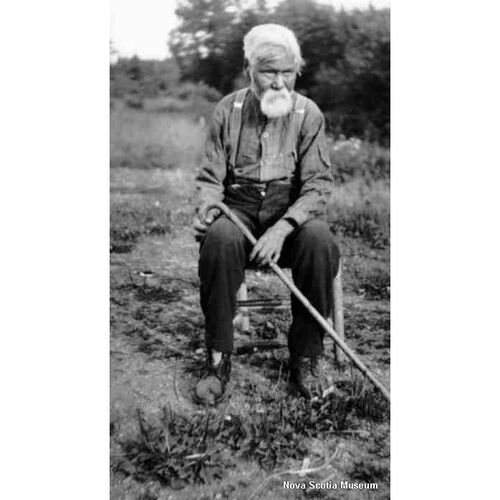

A final photograph of Glode appeared in the Halifax Herald of 27 July 1932 with this caption: “Well known hunter and guide, James Glode, who celebrated his 101st birthday on Monday at the Micmac reservation, Shubenacadie.… He is in good health and has never used tobacco.”

What this description does not say is that Jim Glode was by then completely blind and mentally wandering. According to Max Basque, he “used to kneel on his cot, kneel on it for hours, paddling and paddling – in his mind he was somewhere in his canoe. And then he’d get up and drag his cot across the room, get on again, and paddle, paddle. He thought he was portaging the canoe, see?”

In December 1932, at the funeral of Peter Wilmot, William Paul, chief of the Shubenacadie Reserve, gave Dennis some information about Glode. “He is fairly well to his body,” Paul explained, “but he is blind and hard to hear.” He died a few years later, released from an endless dream of travelling the rivers and forests of the mind, hunting and guiding.

Photographs of James Glode are found in the “Mi’kmaq portraits coll.,” comp. R. H. Whitehead et al.: museum.gov.ns.ca/mikmaq (consulted 3 Oct. 2012).

N.S. Museum Library (Halifax), mss, Piers papers, Mi’kmaw ethnology: genealogies; material culture, transportation, canoes, 3, 1 Dec. 1924; memoirs and manuscripts; Piers research, sports and sportsmen, box 9, xiv; Sports, fishing and hunting (a) corr., Sarah Stayner to Harry Piers, 8 March 1921, (b) notes, Isaac Sack to Harry Piers, 26 Feb. 1921. NSA, MG 1, vol.2867, no.6; MG 15, vol.5, no.69; “Nova Scotia hist. vital statistics,” Hants County, 1936: www.novascotiagenealogy.com (consulted 13 Aug. 2012); RG 1, vol.430, no.57. Private arch., R. H. Whitehead (Halifax), Notes on conversations with Max and Isaac Basque, July 1976, July 1978, October 1980, July 1987. Halifax Herald, 27 July, 31 Dec. 1932. T. B. Akins, “History of Halifax City,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll. (Halifax), 8 (1892–94): 3–269; repr. as History of Halifax City (Belleville, Ont., 1973). Dominion Illustrated (Montreal), 26 April 1891. The old man told us: excerpts from Micmac history, 1500–1950, comp. R. H. Whitehead (Halifax, 1991).

Cite This Article

Ruth Holmes Whitehead, “GLODE, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/glode_james_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/glode_james_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Ruth Holmes Whitehead |

| Title of Article: | GLODE, JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2013 |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | December 13, 2025 |