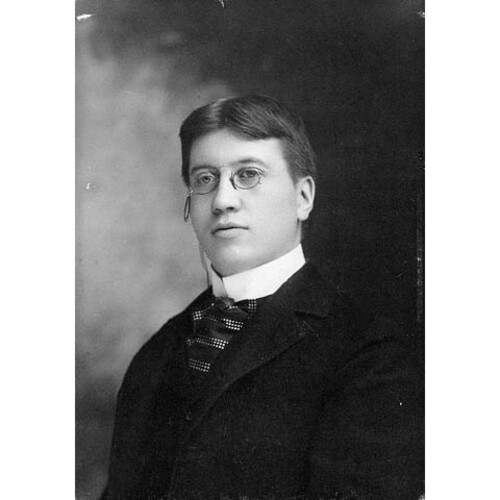

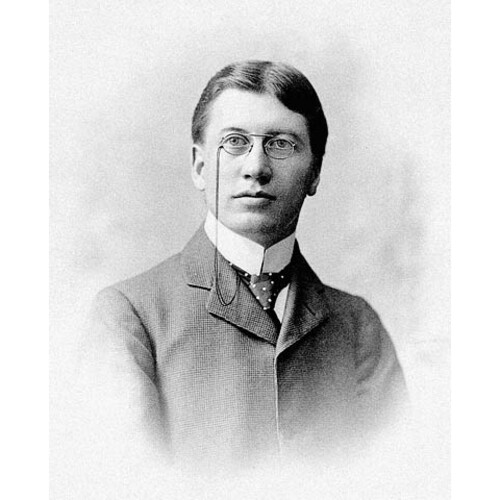

HARPER, HENRY ALBERT, journalist and civil servant; b. 9 Dec. 1873 in Cookstown, Ont., son of Henry Harper and Margaret Ann McClain; d. unmarried 6 Dec. 1901 in Ottawa, and was buried in Cookstown.

Henry Albert Harper’s father was a pharmacist and general merchant in Cookstown; in 1880 the family moved to Barrie, where Harper Sr became an insurance agent. Albert, known to his friends as Bert, graduated from Barrie Collegiate Institute in 1891 and the University of Toronto with an honours degree in political science in 1895. After some hesitation about his career, he became a journalist. He worked briefly for the London Advertiser (London, Ont.), the London News, and the Toronto Daily Mail and Empire, and then as Ottawa correspondent for the Montreal Daily Herald. He resigned from that position to become associate editor in October 1900 of the month-old Labour Gazette, in the newly founded federal Department of Labour; the editor and deputy minister was 25-year-old William Lyon Mackenzie King*, whom he had met at university.

A serious-minded Presbyterian, Harper was committed to self-improvement, drew moral sustenance from Carlyle, Tennyson, and Matthew Arnold and from the beauties of nature, and was dedicated to social harmony and justice. King shared this rather priggish idealism. The two young men lived together in an apartment in Ottawa, spent the summer of 1901 in the Gatineau hills, and talked at length of their feelings and ambitions.

King was the dominant figure, and he associated Harper with his plans for the development of the labour department. When he was away from Ottawa mediating labour disputes, Harper functioned as acting deputy. The two men assumed that harmonious industrial relations were part of the Christian social order. Some capitalists and even some workers might be incorrigible, but, as Harper put it, “most industrial disputes have their origins in misunderstandings.” He and King envisaged the Labour Gazette as a significant contribution to industrial peace. By publishing an objective record of statistics and facts, they would promote understanding, foster conciliation, and provide a reliable basis for social analysis and the formation of labour policy. Because King was busy with labour conciliation and raising his own profile, it was left to Harper to collect data and oversee the editing and publication of the monthly journal. He established its main features, including regional correspondents’ reports, cost-of-living data, accounts of strikes and settlements, and other contemporary labour news. The Canadian Manufacturers’ Association had reservations about its objectivity, but Harper’s balanced editing, backed up by his belief in social harmony, averted partisan attacks.

Best remembered as King’s friend, Harper might have come to resent King’s demands on his time or even to question King’s disinterested idealism, but he died young. He drowned in a heroic but unsuccessful attempt to save a young woman, Elizabeth (Bessie) Blair (daughter of Andrew George Blair, the minister of railways and canals), who had gone through the ice while skating on the Ottawa River. King was largely responsible for the statue of Sir Galahad, the pure knight of Arthurian romance, which was erected in 1905 on Wellington Street in front of the Parliament Buildings to commemorate Harper’s heroism. As well, he wrote a memorial volume, The secret of heroism, which lauds Harper’s idealism and blatantly draws attention to King’s virtues at the same time.

AO, RG 22, ser.315, nos.4201, 4203. NA, MG 30, A28. Northern Advance (Barrie, Ont.), 12, 19 April 1900; 12 Dec. 1901. J. J. Atherton, “Department of Labour and industrial relations, 1900–1911” (ma thesis, Carleton Univ., Ottawa, 1972). Paul Craven, “An impartial umpire”: industrial relations and the Canadian state, 1900–1911 (Toronto, 1980). R. MacG. Dawson and H. B. Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King: a political biographv (3v., Toronto, 1958–76), 1. W. S. Drinkwater, “The story of the Labour Gazette,” Labour Gazette (Ottawa), 75 (1975): 587–90. H. S. Ferns and Bernard Ostry, The age of Mackenzie King: the rise of the leader (London, 1955). Sandra Gwyn, The private capital: ambition and love in the age of Macdonald and Laurier (Toronto, 1984). W. L. M. King, The secret of heroism; a memoir of Henry Albert Harper (New York, 1906). Labour Gazette, 1 (1900–1 ); 2 (1901–2): 326. C. P. Stacey, A very double life: the private world of Mackenzie King (Toronto, 1976).

Cite This Article

H. Blair Neatby, “HARPER, HENRY ALBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/harper_henry_albert_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/harper_henry_albert_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | H. Blair Neatby |

| Title of Article: | HARPER, HENRY ALBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |