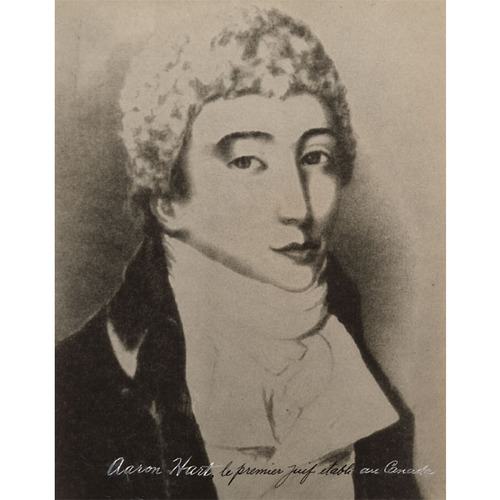

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

HART, AARON, businessman; b. c. 1724, perhaps in Bavaria (Federal Republic of Germany), but more likely in England; d. 28 Dec. 1800 at Trois-Rivières (Que.).

Nothing is known of Aaron Hart’s origins. Family tradition long kept up the legend of a regiment named the Hart New York Rangers which was supposed to have joined Amherst’s troops at the time of the conquest of Canada. Some Jewish historians have made of Aaron Hart an officer serving with the British forces and on Amherst’s general staff. More realistically, the scholarly J. R. Marcus alleges that he was a purveyor, a sutler who is believed to have followed the troops. At that time the commissariats of European armies did in fact welcome many Jews. A masonic certificate dated 10 June 1760 at New York is the earliest document known to refer to Aaron Hart; having made up his mind to follow Amherst and Haldimand’s troops northwards, Hart had probably considered it wise to provide himself with a sort of letter of introduction. Military documents, however, never mention his presence, and the next known reference to him is a receipt dated 28 March 1761 which indicates that he and Eleazar Levy had supplied merchandise to Samuel Jacobs. On 21 Oct. 1761 Jacobs wrote to Hart, and thereafter a regular correspondence confirms Aaron Hart’s presence in Trois-Rivières.

In May 1762 Haldimand took over the administration of Trois-Rivières while the governor, Ralph Burton*, was absent. He became patron to Hart, who was already purveyor to the troops quartered there. On 4 July 1762 a fire broke out in the town; according to Haldimand, “the merchant Hart, an English Jew who has suffered the most, may have lost [£]400 or 500.” Three days later notary Paul Dielle drew up a lease between Théodore Panneton the younger and Aaron Hart. On 23 Aug. 1763 the authorities opened a post office at Trois-Rivières “in the house of Mr. Hart, merchant” that was to remain there for seven years. In the summer of 1764 Haldimand, now officially governor, wrote to Gage that “the group of British merchants in Trois-Rivières” was “composed of a Jew and of a sergeant and an Irish soldier on half pay.” Hart soon became interested in the fur trade. He engaged the best-known voyageurs in the region, among them Joseph Chevalier, Louis Pillard the younger, and Joseph Blondin. His initiatives paid off and he continued to expand this lucrative undertaking.

On 7 Feb. 1764 Aaron Hart acquired his first land, buying 48 acres from the Fafard de La Framboise estate for the attractive price of £350 in cash. Seven months later he purchased a large section of the seigneury of Bécancour. In May 1765 part of the Bruyères fief came into his possession; within six months he had paid off the £500 Simon Darouet demanded for it. His enthusiasm for acquiring new properties never diminished. Hart foresaw the extraordinary possibilities present in this country, newly conquered by the British. Believing in its progress, its development, he thought of establishing a solid dynasty in Canada and he methodically laid the foundations. In 1767, convinced of the promise of his new country, he went to London to take a wife. On 2 Feb. 1768 he married Dorothy Judah and through his marriage found himself at the centre of a large family connection. One of Aaron’s brothers, Moses, had already joined him in his ventures; another, Henry, had settled at Albany, New York, and a third, Lemon, was launching the London Red Heart Rum distillery in London. At least two of Dorothy Judah’s brothers, Uriah and Samuel, had gone to Canada ahead of her. Their correspondence indicates that “Mama Judah” lived in New York around 1795. The same letters give information about the close links which joined the couple to the large interrelated circle of Jews in New York, principal members being the Gomezes, Meyers, Levys, Cohens, and Manuels.

Upon his return from London in the spring of 1768 Aaron rejoined his brother Moses, who had kept a successful watch over his business affairs. Aaron dreamt of a large family and never missed a piece of land for sale or a landowner short of funds. He made loans easily and was willing to bide his time, letting the debt increase; then he would ask for security, suggest a mortgage. The old seigneurs, defeated in 1760, became his steadiest clients, and he showed some sympathy for them. He became, as it were, the accomplice of Joseph-Claude Boucher* de Niverville, Charles-Antoine Godefroy de Tonnancour, Jean-Baptiste Poulin de Courval Cressé, and Jean Drouet de Richerville. Through generous and discreet loans he made the post-conquest period almost attractive for them. Time enough later to brandish his claims in front of the heirs, who, caught unawares, would scarcely know where to turn. The future belonged to the new settlers, English, Scottish, or Jewish. Aaron Hart grasped the true meaning of the events that had opened the valley of the St Lawrence to him and his people. The fact that only a small number of English speaking persons had settled in the province prompted the British to rely on Jewish merchants. The latter regarded themselves as British and attached their names to the numerous petitions drawn up by His Majesty’s old subjects. They established themselves throughout the new British colony: Eleazar Levy, Elias Salomon, Levy Simons, Hyam Myers, Abraham Franks, and some others at Quebec; Moses Hart, Aaron’s brother, in Sorel; Uriah Judah in Verchères; Pines Heineman in Saint-Antoine-de-Padoue, Rivière-du-Loup (Louiseville); Emmanuel Manuel in Sainte-Anne-d’Yamachiche (Yamachiche); Joseph Judah and Barnett Lyons in Berthier-en-Haut (Berthierville); Samuel Jacobs in Saint-Denis, on the Richelieu; Chapman Abraham, Gershom, Simon, and Isaac Levy, Benjamin Lyons, Ezekiel and Levy Solomons, David Lazarus, John and David Salisbury Franks, Samuel and Isaac Judah, Andrew Hays, and many others in Montreal. This list, compiled mainly from the business papers of Aaron Hart and Samuel Jacobs, is in no way complete. Most of these Jews had arrived in the province of Quebec at the time of the conquest or shortly thereafter. Some had first engaged in fur-trading in the Great Lakes region, and then had come to Quebec and Montreal around 1763; others had come directly with the troops. For instance, Samuel Jacobs was at Fort Cumberland (near Sackville, N.B.) in 1758 and then followed in the wake of the 43rd Foot and Wolfe*’s troops, reaching Quebec in the autumn of 1759.

Samuel Jacobs could in fact easily rival Aaron Hart for recognition as the first Canadian Jew. Both engaged in business on a large scale and left evidence of their activity that could supply valuable material for a whole generation of historians. For his Jewish compatriots, however, Aaron Hart’s good fortune lay in having made a Jewish marriage and having been able to bring up his children, or at least his sons, in Jewish traditions. Since he lived to a respectable age, he also had the opportunity of initiating them into business himself. From 1792 he associated them closely with his enterprises. While the eldest, Moses*, went off to try his luck at Nicolet, and then at Sorel, Aaron gave his shop on Rue du Platon over to the firm of Aaron Hart and Son and entrusted specific responsibilities to Ezekiel*. When Moses returned he converted the company and also took advantage of the occasion to bring young Benjamin in. Carrying out a plan conceived earlier, Aaron and his sons opened a brewery across from the Ursuline convent, near the St Lawrence. By assigning large landed properties to his sons, especially the two eldest, he quite simply forced them to establish themselves at Trois-Rivières, the chosen birthplace for the Hart dynasty.

In the spring of 1800 Aaron fell ill. He fought against his illness until mid December, and then he resolved to dictate his will, “bearing in mind that there is nothing so certain as death and so uncertain as the moment of its coming.” His eldest son, Moses, was to inherit the seigneury of Sainte-Marguerite and the marquisate of Le Sablé, Ezekiel the seigneury of Bécancour, Benjamin the main store, and Alexander two plots in town. To his four daughters, Catherine, Charlotte, Elizabeth, and Sarah, he left the sum of £1,000 each, but he attached all sorts of conditions linked in particular to their marriages and their prospective offspring. Clauses of the will invariably restore assets to those who bear the Hart name. The inventory of his property carefully drawn up by notaries Joseph Badeaux* and Étienne Ranvoyzé* reveals not only the merchant’s fortune, but also his practices and dodges. He had several bags containing large reserve funds in Spanish piastres. As for moneys owing, their entry covered 11 pages in the notaries’ ledger. Not a single parish within a radius of 50 miles could boast of not having at least one inhabitant who was in debt to Hart. Of these innumerable debts, only one left unpleasant memories. In 1775, at the time of the American invasion, the Trois-Rivières merchant had supplied both sides; the Americans had paid him in paper money that had still not been honoured a quarter of a century later. For the rest, the heirs had excellent prospects. At the time of the abolition of the seigneurial system, the lists prepared by a descendant of the Judahs around 1857 revealed that the Hart clan owned entirely or in part four fiefs (Boucher, Vieux Pont, Hertel, and Dutort) and seven seigneuries (Godefroy, Roquetaillade, Sainte-Marguerite, Bruyères, Bécancour, Bélair, and Courval). The total of the cens et rentes and the lods et ventes amounted at that time to $86,293.05.

Although in large measure supplanted, the people of Trois-Rivières had not had their final word: in 1807 they elected Ezekiel Hart to the assembly. Without quite realizing it, Ezekiel to some extent was becoming one of them. Three or four generations later the Harts would experience more fully the true meaning of the deep-rooted and tenacious resistance of the “long-time Canadians.” Gradually Aaron Hart’s descendants would blend into the French speaking and Catholic population of Trois-Rivières which had somehow managed to live through the drama of 1760. Some joined the ranks of the Anglo-Protestants for a time; yet hundreds of Aaron Hart’s descendants, who were firmly attached to their properties, refused to lose everything by leaving a region which resolutely remained French and Catholic. They chose to remain there, though threatened with slow but inexorable assimilation by the local majority. Today some of them jealously guard the secret of their origins and of their relative prosperity; many others are completely ignorant of them. Aaron Hart could not foresee this curious historical reversion in which those defeated in 1760 would gradually become vehicles of assimilation. The Harts of the Trois-Rivières region would have the same experience as the Burnses, Johnsons, and Ryans: mingling with the “long-time Canadians” they too would become the progenitors of the Québécois of today.

[The papers of the Hart family are held at the Archives du séminaire de Trois-Rivières in the Fonds Hart, estimated by Marcel Trudel to contain about 100,000 items in 3,000 folders. Hervé Biron, who classified the material, has drawn up a 98-page inventory entitled “Index du fonds Hart.” The papers constitute the richest collection of documents tracing the history of the Jews in Canada from 1760 to 1850. During this period in which Sephardic Jews were dominant, the Hart family allied itself to most of the Jewish families in Canada and the United States. The Jacobs papers at PAC (MG 19, A2, ser.3), which form part of the Ermatinger family collection and comprise more than 300 volumes, cover a much shorter period, from 1758 to 1786. To the present, only one Jewish historian, J. R. Marcus, director of the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati, Ohio, and author of Early American Jewry (2v., Philadelphia, 1951–53), has studied these two important collections in depth. Under the auspices of the Canadian Jewish Congress, a Canadian Jewish historian, B. G. Sack, published History of the Jews in Canada, trans. Ralph Novek, [ed. Maynard Gertler] ([2nd. ed.], Montreal, 1965); it is a general survey of uneven historical value. Using the Hart papers, Raymond Douville brought out an interesting biography of Aaron Hart entitled Aaron Hart; récit historique (Trois-Rivières, 1938). In Les Juifs et la Nouvelle-France (Trois-Rivières, 1968), Denis Vaugeois details the story of the first Canadian Jews. It is interesting to note that L.-P. Desrosiers drew inspiration from the lives of Aaron Hart and Nicolas Montour for his novel Les engagés du Grand-Portage (Paris, 1938). A number of documents relating to Aaron Hart may be found in AUM, P 58, and in the McCord Museum, Montreal. d.v.]

Chronological list of important events in Canadian Jewish history, comp. Louis Rosenburg ([Montreal], 1959). Printed Jewish Canadiana, 1685–1900. . . , comp. R. A. Davies (Montreal, 1955). A selected bibliography of Jewish Canadiana, comp. David Rome (Montreal, 1959). A. D. Hart, The Jew in Canada (Toronto, 1926).

Cite This Article

Denis Vaugeois, “HART, AARON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 10, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hart_aaron_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hart_aaron_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Denis Vaugeois |

| Title of Article: | HART, AARON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | March 10, 2026 |