Source: Link

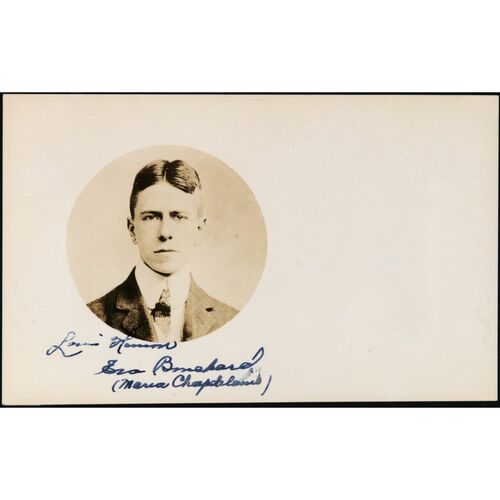

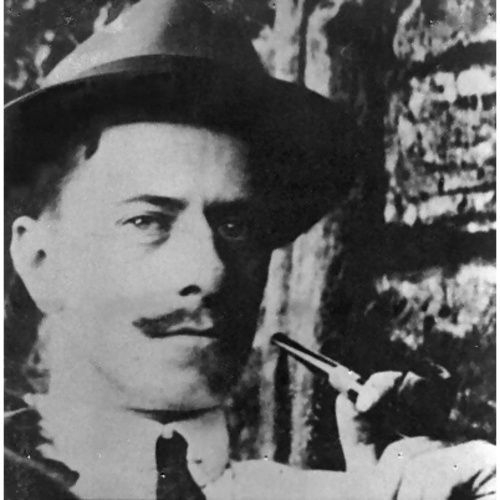

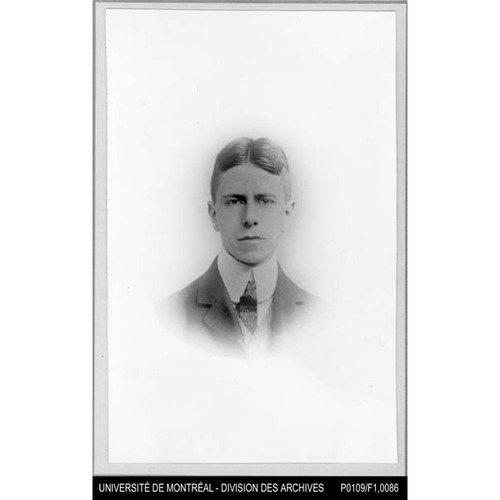

HÉMON, LOUIS (named Louis-Prosper-Félix at birth), author; b. 12 Oct. 1880 in Brest, France, third and last child of Félix Hémon and Louise-Mélanie Le Breton; d. accidentally 8 July 1913 in Chapleau, Ont.

Louis Hémon belonged to a distinguished Breton family. His paternal grandfather was a teacher at the Collège de Quimper. His uncle Louis was the deputy for Quimper for 32 years, and a senator, and his uncle Prosper a historian of considerable merit and repute. Another uncle, Charles, had a career in the colonies, first in Tonkin (Vietnam) and Cochin China (Vietnam), and later in North Africa. Alain Le Grand observes that “by his independent character and spirit of adventure, Uncle Charles was the predecessor . . . of Louis, the novelist,” who would also be obsessed by the urge to leave home. Louis’s father, Félix, who wrote poetry when the spirit moved him and carried on a brief correspondence with Victor Hugo, taught at various lycées before becoming private secretary to the minister of public instruction, Armand Fallières, and later an inspector general in this department. An officer of the Legion of Honour, he was the author of numerous literary studies, including a laudatory work on the Comte de Buffon (1878) and a Cours de littérature française published in Paris from 1889 to 1907, which won an award from the Académie Française. On his mother’s side, Hémon was the grandson of Charles-Louis Le Breton, a medical assistant at the capture of Algiers and a member of the Assemblée Nationale in 1871.

Louis Hémon was two years old when his parents moved to Paris. His childhood there was stormy, as he recalls in the somewhat humorous self-portrait he penned for the “Livre d’or” of the Paris sports journal Le Vélo on 8 May 1904: “From childhood, have shown signs of athletic pugnacity, kicking the shins of opponents whose height, weight, and reach denied me a more classic style of play.” His memories of his youth were sombre. “Ten years as a day student in a dark lycée – dreary studies. All fighting spirit vanished under the slow oppression of Greek composition.” He went to the Lycée Montaigne in 1887 and later, in 1893, the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, and attained his graduation diploma at the age of 15 by special permission, since the minimum age required was 16. Passing his university entrance examinations in 1897, he enrolled at the Sorbonne, where he obtained an llb on 8 Jan. 1901, an lll in maritime law on 31 Aug. 1901, and, with a view to entering the École Coloniale, a diploma in the Annamese language, granted by the École Nationale des Langues Orientales Vivantes on 16 Dec. 1901.

Hémon spent summer holidays in Oxford, England. He was there from July to 3 Oct. 1899 and again from 13 Aug. 1901 until the autumn of that year, and he dispatched some 15 letters to his mother. In November 1901 he was in Chartres, France, doing his military service. He wrote to his mother anxiously on 4 December: “At the moment, for one reason or another we do nothing from morn till night. I have not attained any rank as yet. My appetite is good and I am getting a little more mindless every day.” Fortunately, he fell in with an athletic group and could pass all the time he wanted at sports, the merits of which he would extol a few years later in the columns of Le Vélo (subsequently the Journal de l’automobile . . . and then L’Auto).

On 19 Sept. 1902 – two years before his time was up – Hémon was released from military service because of his status as a student. He returned to Paris and went with his mother and his sister Marie on a holiday in Normandy. It is hard to know what made him decide, on his return, to seek voluntary exile in London, when his father had intended him to have a career as a diplomat. Perhaps he quarrelled with his father, who reputedly wanted him to follow in his footsteps by entering the public service. Possibly freedom was so important to him that he abandoned the life of a civil servant, like Jean Grébault, his double, in the short story “Jérôme,” which he would publish two years later. Whatever the reason, the “serious young man” left Paris on 13 Nov. 1902, spent a short time in Oxford, and went on to London, where, besides taking up sports, notably boxing and rowing, he earned his living as a bilingual secretary to several well-established ship-brokers in the centre of the City; the hero of one of his future novels, Amédée Ripois, would support himself this way. In letters to his family, especially his mother, Hémon had little to say about his work or how he spent his time. It is known that he published a piece entitled “La rivière” in Le Vélo on 1 Jan. 1904, for which he won first prize in its “holiday competition.” He became one of its contributors, as noted in the editorial comment accompanying the first of his articles, “Le combat,” published on 20 Jan. 1904. It is hard to identify the other Parisian newspaper referred to in his correspondence on at least two occasions in 1903; he alluded sarcastically to “people dense enough to buy my prose,” which, to his regret, did not come out “on set days.” He himself discreetly avoided naming “the paper in question.” In any case, he supplied four pieces to Le Vélo early in 1904 and on 23 March began writing regularly for it. On 7 Aug. 1905, for unknown reasons, his contributions ceased. He had had time, however, as the paper’s London correspondent, to publish his first 24 sports stories (collected under this head in 1982), and some 125 sports columns, for the most part appearing under the title “Lettre d’Angleterre” or “Angleterre,” as well as nearly 100 unsigned telegrams identified as from the paper’s correspondent of which he had claimed authorship at the beginning of some columns. These writings leave no doubt about Hémon’s interest in sport, especially amateur sport, and show that he thought it should be taken up for pleasure and fitness, rather than for prizes or attention. He tells his own story in “Histoire d’un athlète médiocre,” “Jérôme,” “Marches d’armée,” “Mon gymnase,” and the pieces he penned in Quebec.

Hémon won a literary competition sponsored by L’Auto with a short story entitled “La conquête,” which came out on 12 Feb. 1906. On 29 Oct. 1909 he began contributing occasionally to this paper, which carried twenty-four of his stories, the final eight written in Quebec.

Meanwhile, Hémon devoted himself to writing longer works, beginning with eight short stories eventually collected in 1923 under the title La belle que voilà. . . . Two of them appeared in newspapers during his lifetime, “La peur” (Le Vélo, 15 Oct. 1904) and “Lizzie Blakeston” (Le Temps (Paris), 3–8 March 1908). Six are set in the East End of London. The frequency with which he used this working-class setting shows his fondness for ordinary poor people.

Hémon wrote his first three novels in London between 1907 and 1911 and sent them to the publisher Bernard Grasset as soon as they were finished, but without success. Colin-Maillard, written before October 1908 but not brought out until 1924, tells the story of Mike O’Brady’s long, slow search for truth and freedom. In Battling Malone, pugiliste, which appeared in 1925 but was written in 1909, the novelist describes the swift rise and abrupt fall of an Irish boxer who competes for the world light-heavyweight championship, but meets his Waterloo in Paris when he loses on points to a French opponent. Monsieur Ripois et la Némésis, the only novel he set in middle-class London, concerns the escapades of Amédée Ripois, a French exile of lowly origins, a selfish, sensual, vain, and cruel man who dreams of seducing every woman he meets. It would not be published until 1950, probably to avoid jeopardizing the success of Maria Chapdelaine: récit du Canada français, the masterpiece he wrote in the Lac Saint-Jean region in 1912–13, which has been appropriated by the Catholic clergy and the political right.

Hémon had embarked for Canada on 12 Oct. 1911. He spent some time in Montreal working for an insurance company, then took a job as a farm labourer with Samuel Bédard, a farmer in Péribonka, and went to the Lac Saint-Jean district in July 1912. A little pioneer village there is the setting for the novel Maria Chapdelaine, which tells the story of two settlers and their six children, particularly Maria, a “simple and sincere” girl, “close to nature,” to whom three men of different backgrounds propose marriage. After waiting in vain for the one she loves, François Paradis, a coureur de bois who perishes in a storm, she decides to reject Lorenzo Surprenant’s invitation to follow him to the United States, where he has found a good job, and agrees to marry her neighbour Eutrope Gagnon, who offers her a continuation of her peasant life. Issued serially in Le Temps from 27 Jan. to 19 Feb. 1914, the novel was republished in Montreal in 1916 with original illustrations by Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté*, through the good offices of Louvigny de Montigny*, a translator for the Senate, who signed the preface to the Canadian edition along with Émile Boutroux of the Académie Française.

This novel, which soon became widely known, was acclaimed by a few Canadian critics at the time of its publication in Montreal. Ernest Bilodeau, in Le Nationaliste on 7 Jan. 1917, unhesitatingly described it as “a kind of masterpiece, both in form and in terms of accuracy and truth of observation.” He even predicted the book’s success, noting that it “will live in Canadian literature, and at the same time [its author’s] memory will be reverently preserved, both by the good people who knew him during his lifetime and by the countless readers that this honest and truthful book will certainly have.” That astonishing comment – to say no more – should silence those who have claimed that French Canadian critics denigrated Hémon’s work until ultra-conservative French critics hailed it as a masterpiece.

As Gabriel Boillat’s thoroughly researched study proves, the novel met with exceptional success as a result of an advertising campaign that was well orchestrated, at least initially. It has been translated into more than 20 languages and by the late 20th century had gone through nearly 150 editions, with more than 10 million copies distributed worldwide. According to Jean Bruchési, Maria Chapdelaine “brought Canada into world literature.” Claude-Henri Grignon* is convinced that Louis Hémon “stole [from French Canadians] a masterpiece [drawn] from [their] roots.” It must certainly be acknowledged that the young writer proved a keen observer. He painted from life the rough pioneers he had seen at work, whose hard existence he had shared for a time at Péribonka, since he had been assigned as a day labourer on the route of the future Lac-Saint-Jean railway.

In the spring of 1913 Hémon went to Montreal, where he put the finishing touches on the manuscript of Maria Chapdelaine. In June, after sending a copy to Le Temps, he decided he would set out to conquer the vast expanses of the west where, he told his mother, he hoped to work on the harvest. Shortly before he left, he sent a scathing letter to his father, who had discovered, on reading a letter from London addressed to Louis, that there was “a four-year-old girl, of whom [he is] undoubtedly the father,” although there had been “in this case neither marriage nor seduction.” Hémon acknowledged paternity of Lydia-Kathleen, the child of an affair with actress Lydia O’Kelley; born in London on 12 April 1909, she died in Quimper on 26 April 1991. On 8 July 1913, as he was on his way west, Hémon was struck and killed by a train in Chapleau, Ont. There remains some doubt about this tragic death, despite the investigation carried out by Alfred Ayotte, a journalist with La Presse of Montreal, whose findings were published in 1974. To writer Jacques Ferron*, for example, Hémon’s death had the appearance of a suicide.

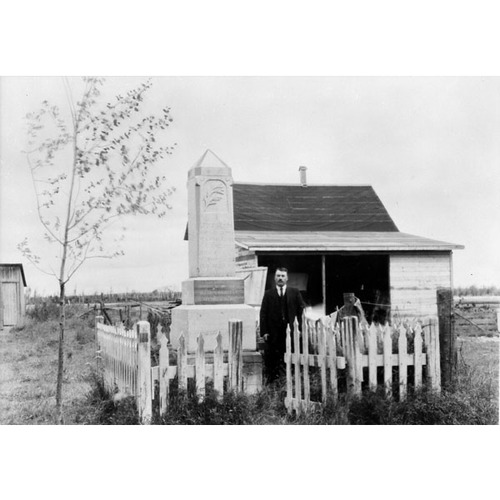

In 1919 the Société des Arts, Sciences et Lettres de Québec, on the initiative of the journalist and author Damase Potvin*, erected a monument to commemorate Louis Hémon. On 10 June 1938 the Université de Montréal conferred a posthumous honorary doctorate on him. Splendid celebrations were held in Péribonka and Chapleau in 1963 to mark the 50th anniversary of his death. In 1980 the centenary of his birth was marked by celebrations and an exhibition in Péribonka. The exhibition was also put on display in Paris and in Brest, Hémon’s birthplace, where an international symposium was being held on the man and his work. In 1982 the Société des Amis de Louis Hémon was founded, and on 5 June 1985 the Musée Louis-Hémon was officially opened in Péribonka. All these events and demonstrations bear witness once again to the success of a work and an author that profoundly influenced the imagination of Quebec.

Louis Hémon remains an important writer who made Quebec known, first in France and then throughout the French-speaking world. It is not surprising that he is the subject of many papers, theses, studies, and articles. Film makers have also shown interest in his work. Julien Duvivier directed Maria Chapdelaine in 1934, as did Marc Allégret in 1950 and Gilles Carle in 1983. René Clément adapted Monsieur Ripois (without La Némésis) for the screen in 1954, and Gérard Philipe had the title role. A definitive bibliography, however, has still to be compiled.

[Aurélien Boivin’s edition of Louis Hémon’s Maria Chapdelaine: récit du Canada français, published in Montreal in 1982, includes (pp.203–18) a comprehensive bibliography of the various editions and translations of the novel, as well as a listing of Hémon’s other writings. Boivin is also the editor of Hémon’s Œuvres complètes (3v., Montréal, 1990–95). Most of Hémon’s writings appeared during his lifetime in various periodicals in France before being issued posthumously in volume form. a.b.]

ANQ-SLSJ, Coll. Mgr Victor Tremblay, SSH, fonds Alfred Ayotte. Arch. Départementales, Finistère (Quimper, France), État civil, Brest, 14 oct. 1880; 102 J (fonds Félix Hémon). Ernest Bilodeau, “Sur un livre canadien écrit par un Français,” Le Nationaliste (Montréal), 7 janv. 1917: 4. Alfred Ayotte et Victor Tremblay, L’aventure Louis Hémon (Montréal, 1974). Gabriel Boillat, “Comment on fabrique un succès: Maria Chapdelaine,” Rev. d’hist. littéraire de France (Paris), 74 (1974): 223–53. Aurélien Boivin, “Louis Hémon et les romanciers québécois: influence et récupération du discours,” Canadian Studies (Talence, France), 10 (1981): 113–23; “Maria Chapdelaine: bilan et perspectives,” in La perspective critique québécoise, sous la direction de P.-L. Vaillancourt et Sylvain Simard (Ottawa, 1985), 93–109. Jean Bruchési, “Louis Hémon,” L’Action française (Montréal), 5 (1921): 749–53. Nicole Deschamps et al., Le mythe de Maria Chapdelaine (Montréal, 1980). DOLQ, vol.2. [C.-H. Grignon], “Médecin, guéris-toi toi même (lettre à monsieur Louvigny de Montigny),” Les Pamphlets de Valdombre (Sainte-Adèle, Qué.), 2 (1938): 151–72. Alain Le Grand, “Charles, le quatrième fils Hémon (1857–1907),” in Colloque Louis Hémon, Quimper ([Quimper], 1986), 209–13. “Présentation du colloque du centenaire de la naissance de Louis Hémon, Brest, 21–23 novembre 1980,” Canadian Studies, 10: 3–138. A.-P. Segalen, “Félix Hémon (1848–1916),” and G.-M. Thomas, “Louis Hémon, avocat, journaliste, poète et parlementaire (1844–1914),” in Colloque Louis Hémon, Quimper, 199–207 and 177–83 respectively.

Cite This Article

Aurélien Boivin, “HÉMON, LOUIS (Louis-Prosper-Félix),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 9, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hemon_louis_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hemon_louis_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Aurélien Boivin |

| Title of Article: | HÉMON, LOUIS (Louis-Prosper-Félix) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 9, 2026 |