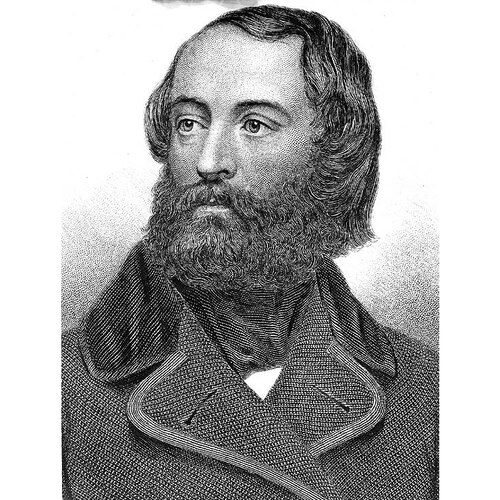

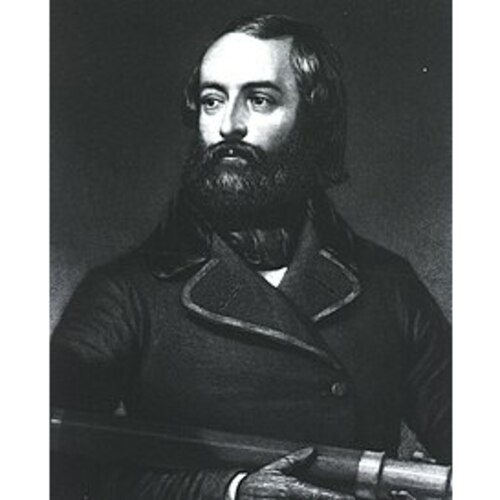

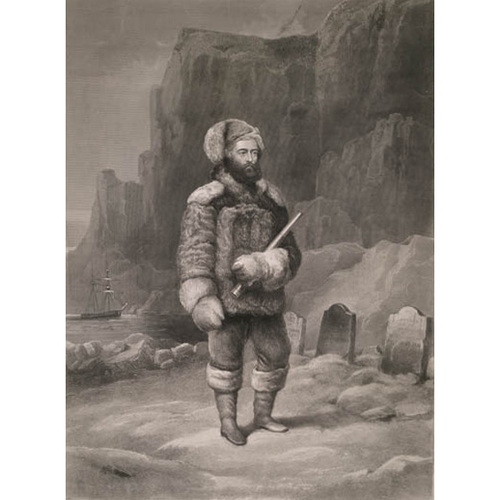

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

KANE, ELISHA KENT, surgeon, naval officer, explorer, and author; b. 3 Feb. 1820 in Philadelphia, eldest of six sons and one daughter of John Kintzing Kane, a distinguished jurist, and Jane Duval Leiper; d. 16 Feb. 1857 in Havana.

Having decided to pursue a career in civil engineering, Elisha Kent Kane entered the University of Virginia at Charlottesville in 1837. The following year, however, a severe attack of rheumatic fever forced him to withdraw and left him with a permanently damaged heart. A small, slight man, Kane possessed a courage and stamina which helped him to overcome this handicap and which served him well in later years. In the fall of 1839 he began the study of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in his native Philadelphia, and after a residency in the hospital of the Blockley Almshouse he graduated in March 1842. On the advice of his father, Kane applied for service in the United States Navy and then, in May 1843, while awaiting his commission, he left for China as the physician attached to the diplomatic mission headed by Massachusetts statesman Caleb Cushing. Kane travelled extensively in the Orient and, after leaving the legation in June 1844, he conducted a hospital boat at Whampoa (Huang-pu), China, for six months before making his way back to the United States by way of Egypt and Europe, arriving at Philadelphia in late summer 1845. His naval commission as assistant surgeon had become official on 1 July 1843. During the next four years, Kane served on various peace-time postings off the west coast of Africa, in the Mediterranean, and along the eastern coast of the United States, besides seeing some action during the Mexican-American War.

In March 1850 Kane applied for service as surgeon to the proposed American expedition in search of Sir John Franklin*, lost in the Arctic since 1845, and received orders on 12 May to join the brig Advance, which, with the brig Rescue, was being outfitted for the mission by the New York merchant Henry Grinnell. Ten days later, under Lieutenant Edwin Jesse De Haven*, commander of the expedition, and Passed Midshipman S. P. Griffin, the two vessels sailed from New York with instructions to search in the vicinity of Barrow Strait (N.W.T.), northward in Wellington Channel, and westward to Cape Walker. The ships followed the south shore of Lancaster Sound to Port Leopold, and then turned north to Beechey Island where at the end of August they joined with the search expeditions of William Penny*, Sir John Ross, and Captain Horatio Thomas Austin*. Kane noted in his journal that on 28 August there were seven ships, under three different commands, “within hailing distance” of Beechey Island and that two other vessels under Captain Erasmus Ommanney were only 15 miles to the west, embedded in the ice. While Kane was at Beechey Island traces of Franklin’s expedition were found, indicating that his two vessels, Erebus and Terror, had passed the winter of 1845–46 there. The Advance and the Rescue then continued westward to Griffith Island before turning back on 13 September. At the southern end of Wellington Channel the ships were beset in the ice and forced to winter in Arctic waters. Drifting with the ice, first north, then south and east out of Lancaster Sound into Baffin Bay, they were finally released in June 1851. After an unsuccessful attempt to find a route through the ice-pack that would take his ships north to continue the search, De Haven set sail for New York where the expedition arrived safely at the end of September.

Kane then applied himself to writing a narrative of the voyage, The U.S. Grinnell expedition in search of Sir John Franklin, and delivering lectures before various scientific bodies. A believer in the hypothesis of an open polar sea, he persuaded Grinnell, American financier George Peabody, the United States Navy Department, and several scientific societies to sponsor a second expedition to go north from Baffin Bay to the shores of the “Polar Sea” in search of Franklin. This expedition was unusual in that Kane, a medical officer, was assigned to command its only vessel, the Advance, and, because of the mixed crew of naval personnel and civilians, naval rules did not altogether apply. From the outset Kane faced problems of morale and discipline with the crew.

Leaving New York on 30 May 1853, the Advance stopped at the fishing port of Fiskenæsset, Greenland, at the beginning of July where the Inuit hunter Hans* Hendrik joined the crew. On 20 July Kane put in to Upernavik and engaged the Danish sledge driver and interpreter Johan Carl Christian Petersen. The Advance then proceeded up the west coast of Greenland and into the sound Kane named Peabody Bay (later renamed Kane Basin) where, by the end of August, its northward progress was stopped by the ice. While the vessel was being prepared in its wintering berth at Rensselaer Harbour, boat and sledge excursions reached as far north as 79°50´ During a winter that saw temperatures drop to –70°F, 57 of the 60 dogs that Kane had acquired for his sledging operations died of Arctic canine hysteria and all members of the expedition suffered to a greater or less degree from scurvy and malnutrition.

In 1854 four sledge expeditions were sent out to explore Peabody Bay. Under Henry Brooks, first officer, eight men left on 19 March to lay supply depots for further exploration. With temperatures as low as –57°F, four of them suffered severely from frost-bite, two dying shortly after their return to the Advance. The ship’s surgeon, Isaac Israel Hayes*, and a crew member made a survey to the southwest in May; James McGary, second officer, and Amos Bonsall headed north across Peabody Bay in June; and the steward, William Morton, accompanied by Hans Hendrik, continued from the point where McGary turned back and reached the northernmost point attained by the expedition, 81°22´ at Cape Independence, Greenland. On 12 July 1854, fearing that the Advance would remain ice-bound, Kane and five men tried to reach Edward Belcher*’s squadron at Beechey Island by boat, but failed. Hayes, Petersen, and seven other crew members then decided to leave the vessel against Kane’s counsel that they would be safer staying with the Advance. On 28 August they headed south in an effort to reach Upernavik on foot, but, having nearly perished, they returned to the ship on 12 December. Kane, who was not a stern disciplinarian, took no punitive action against the group and treated them more like patients than mutineers or deserters. In May 1855, facing the probability of yet a third winter in the ice, Kane abandoned the vessel. In a dramatic 83-day trek, the whole company travelled 1,300 miles on foot and by boat to Upernavik; they were then taken aboard a Danish vessel which carried them to Godhavn on Disko Island. In early September the American ships Release and Arctic, sent out in search of them, arrived at Godhavn and returned them to the United States. In light of the extreme hardship encountered during this expedition it is remarkable that all but three of the participants survived the ordeal – one crew member had died from malnutrition and two others from exposure.

In the course of Kane’s extensive travels he had contracted a number of different maladies, including “rice fever” (cholera) in China, “plague” (typhoid fever) in Egypt, “coast fever” (bacterial septicaemia) in West Africa, and scurvy several times in the Arctic. On his return to the United States in 1855 he was in very poor health. He nevertheless rapidly completed his account of the expedition, Arctic explorations: the second Grinnell expedition in search of Sir John Franklin, and then visited England in late 1856. Proceeding next to Cuba, where he hoped to find relief from his chronic illness, he died there on 16 Feb. 1857 after two severe strokes. Kane was given a grand public funeral in Philadelphia as America’s first great Arctic explorer and was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery. Although Kane was never publicly married, he had had a continuing association with the spiritualist Margaret Fox from 1855 to 1857 and after his death she claimed to have been his wife.

In his short lifetime Elisha Kent Kane had captured the imagination of America through his travels in the Orient, his brief but illustrious service in the Mexican-American War, and his two Arctic expeditions. Both of his books were well received, and still rank high for literary merit among works on Arctic exploration. His contribution to Arctic medicine could have been substantial if later explorers had paid heed. He stressed adaptation to the environment by means of shelter, clothing, and activity, and he showed that the Inuit way of life was important to survival. Above all he urged a diet of fresh meat as a preventive and cure for scurvy. The route that Kane had followed in 1853 was later favoured by other Arctic explorers, including Isaac Israel Hayes in 1860 and 1869, Charles Francis Hall* in 1871, Sir George Strong Nares in 1875, Adolphus Washington Greely in 1881, Robert Edwin Peary in 1898, 1905, and 1908, and Donald Baxter MacMillan in 1913.

[Elisha Kent Kane is the author of a number of scientific articles, the first of which was his thesis in medicine, “Experiments on kiesteine, with observations on its applications to the diagnosis of pregnancy,” published in American Journal of the Medical Sciences (Philadelphia), new ser., 4 (July 1842): 13–38. On his return from the 1850–51 Arctic expedition he put forth his theory of an open polar sea in a 24-page pamphlet, Access to an open polar sea in connection with the search after Sir John Franklin and his companions (New York, 1853). Four articles prepared from his notes on the 1853–55 expedition and edited by Charles Anthony Schott were published posthumously in Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge (Washington): “Astronomical observations in the Arctic seas . . . ,” 12 (1860), 2nd article; “Magnetical observations in the Arctic seas . . . ,” 10 (1859), 3rd article; “Meteorological observations in the Arctic seas . . . ,” 11 (1859), 5th article; and “Tidal observations in the Arctic seas . . . ,” 13 (1860), 2nd article. The articles were later published as a monograph edited by Schott, Physical observations in the Arctic seas . . . (Washington, 1859–60). Kane’s journal of the 1850–51 expedition, The U.S. Grinnell expedition in search of Sir John Franklin: a personal narrative (London and New York, 1853; new ed., 1854), was well received and was republished by Horace Kephart as Adrift in the Arctic ice pack, from the history of the first U.S. Grinnell expedition in search of Sir John Franklin (New York, 1915). Kane’s account of the second Arctic voyage was also published several times under the title Arctic explorations: the second Grinnell expedition in search of Sir John Franklin, 1853, ’54,’55; illustrated by upwards of three hundred engravings, from sketches by the author (2v., Philadelphia and London, 1856; new ed., 1857; new ed., London, 1861). These works were sufficiently popular to be translated and published in German as Zwei Nordpolarreisen zur Aufsuchung Sir John Franklins, trans. Julius Seybt (Leipzig, [German Democratic Republic], 1857), and Kane, der Nordpolfahrer: Arktische Fahrten und Entdeckungen der zweiten Grinnell-Expedition zur Aufsuchung Sir John Franklin’s in den Jahren 1853, 1854 und 1855 . . . , trans. F. Kiesewetter (2v., Leipzig, 1859). Margaret Fox, in an attempt to prove that her relationship with Kane was in fact a common-law marriage, edited The love-life of Dr. Kane; containing the correspondence, and a history of the acquaintance, engagement, and secret marriage between Elisha K. Kane and Margaret Fox, with facsimiles of letters, and her portrait (New York, 1866), a collection of Kane’s letters, including a few of disputed authenticity.

The American Philosophical Soc. Library (Philadelphia), E. K. Kane papers, includes his correspondence and writings, and the journals of his second expedition are in Pa., Hist. Soc. (Philadelphia), Ferdinand J. Dreer coll., and in Stanford Univ. Libraries (Stanford, Calif.), ms Division, M61. r.e.j.]

I. I. Hayes, An Arctic boat journey, in the autumn of 1854 (Boston, 1860). Cooke and Holland, Exploration of northern Canada. DAB. G. W. Corner, Doctor Kane of the Arctic seas (Philadelphia, 1972). William Elder, Biography of Elisha Kent Kane (Philadelphia and Boston, 1858). Jeannette Mirsky, Elisha Kent Kane and the seafaring frontier (Boston, 1954). S. M. Smucker [Schmucker], The life of Dr. Elisha Kent Kane, and of other distinguished American explorers . . . (Philadelphia, 1858).

Cite This Article

Robert E. Johnson, “KANE, ELISHA KENT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kane_elisha_kent_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kane_elisha_kent_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Robert E. Johnson |

| Title of Article: | KANE, ELISHA KENT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 22, 2025 |