Source: Link

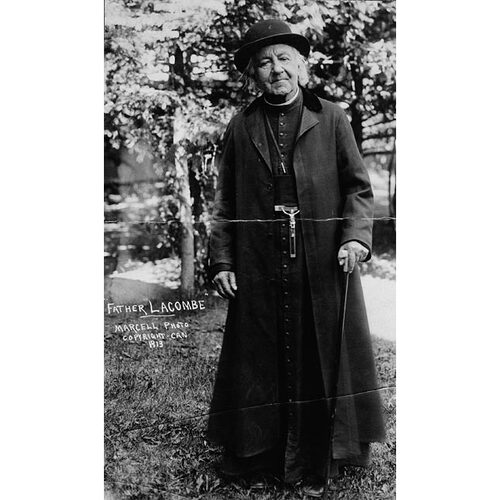

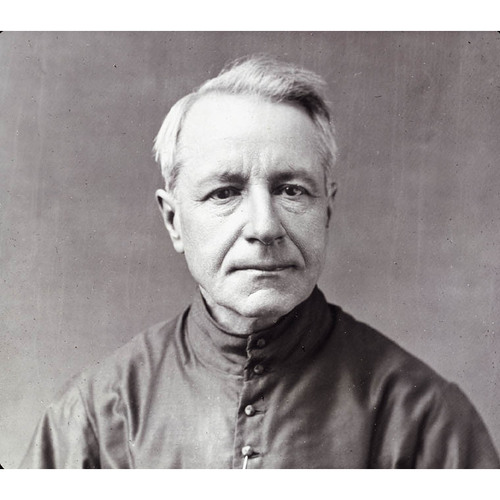

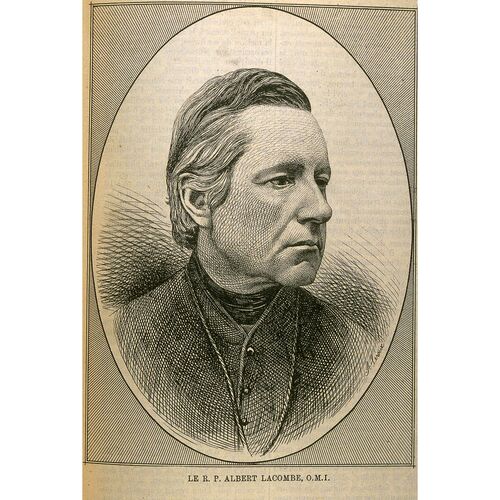

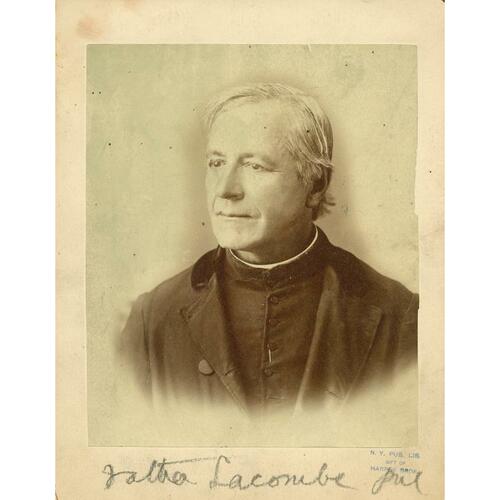

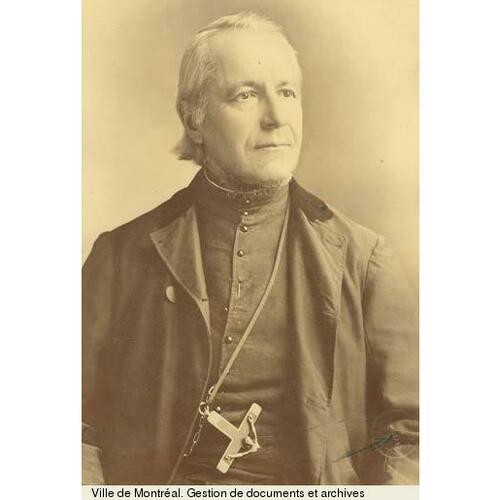

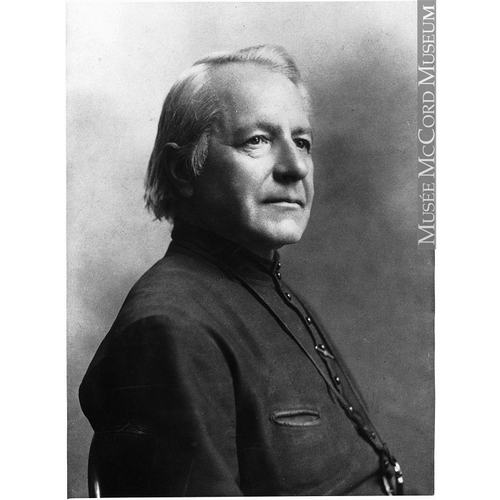

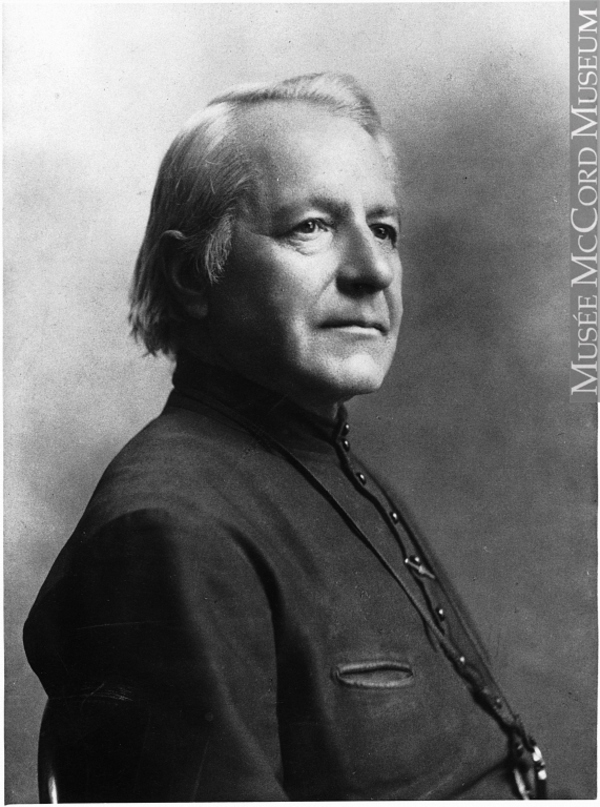

LACOMBE, ALBERT, Roman Catholic priest and Oblate of Mary Immaculate; b. 28 Feb. 1827 in Saint-Sulpice, Lower Canada, son of Albert Lacombe and Agathe Duhamel, dit Sansfaçon, farmers; d. 12 Dec. 1916 in Midnapore, Alta.

Albert Lacombe, one of the best-known missionaries in the history of western Canada, attended the Collège de L’Assomption and continued his theological studies at the bishop’s palace in Montreal. It was there that he met George-Antoine Bellecourt*, a visiting missionary from Red River (Man.) who was raising funds for western missions. Lacombe demonstrated an interest in working in that region and, shortly after his ordination at Saint-Hyacinthe on 13 June 1849, he was sent to Pembina (N.Dak.), which was served by clergy from Red River. There he assisted Bellecourt, and in 1851 he accompanied Métis hunters on the plains.

Lacombe returned east to be assistant priest at Berthier-en-Haut (Berthierville), Lower Canada, in 1851–52 but, since his wish to work in the west was unabated, Bishop Ignace Bourget* of Montreal allowed him to go back to Red River in 1852 with Bishop Alexandre-Antonin Taché*. Lacombe was stationed at Lac Ste Anne (Alta) in 1853. He began his noviciate in the Oblate order in 1855 under René Rémas and became a member of the congregation on 28 Sept. 1856. During his years at Lac Ste Anne, Lacombe visited Jasper House, Fort Edmonton (Edmonton), Lac la Biche, Lesser Slave Lake, and Fort Dunvegan (Dunvegan).

By 1860 Lac Ste Anne was deemed unsuitable as a central mission, and in January 1861 Taché and Lacombe selected a new location a short distance north of Fort Edmonton. Taché named it St Albert in honour of Lacombe’s patron saint. St Albert not only offered better soil and less exposure to frost but also facilitated the evangelization of the Cree and Blackfoot because of its proximity to Fort Edmonton, where they came to trade. As superior of the mission, Lacombe built a flour mill and a bridge on the Sturgeon River, established a school in Fort Edmonton, inaugurated a cart trail to Lac la Biche, and organized the freighting of supplies from Red River.

Unfortunately, Lacombe’s zeal and aptitude as a missionary and his friendship with Taché, who was also Canadian, provoked the jealousy of some French Oblates such as Rémas. As a result, Lacombe asked Taché to relieve him as superior and allow him to work with the Cree and Blackfoot. He was given the task, beginning early in 1865, of initiating an itinerant ministry among the Cree. He established a mission in their midst, Saint-Paul-des-Cris (Brosseau), the earliest Catholic Indian mission in Alberta. Located on the North Saskatchewan River not far from the Methodists’ Victoria mission (Pakan), it gave Lacombe the opportunity to combat the efforts of George Millward McDougall* and John Chantler McDougall. Saint-Paul-des-Cris was the first attempt to found a Roman Catholic agricultural colony among the native people of the region. Land was divided into plots which were sown by the Cree who then left for the summer hunt. They returned later to harvest their crops and then departed for the winter hunt. Lacombe accompanied them and instructed them in their camps. His mission ambulante was imitated by other Oblates.

The life of a travelling missionary was full of danger. Virulent epidemics were sweeping the west and on one occasion nearly claimed Lacombe’s life. Jean L’Heureux found him close to death in 1865 and nursed him back to health. Later that year he was caught in the ongoing war between Blackfoot and Cree. He was camped with the Blackfoot along the Battle River when the Cree attacked and he was grazed by one of their bullets during his attempt to establish a cease-fire.

In 1869 Lacombe spent three weeks in a Blackfoot camp near Rocky Mountain House, where he instructed the people and learned their language. The same year he visited Fort Benton, Mont., and St Louis, Mo., to explore the possibility of supplying the western missions from those centres. He was named to the Board of Health of the North-West Territories during the devastating smallpox epidemic of 1871. In 1872 he was appointed vicar general of the St Albert diocese and was sent back to Quebec to raise funds for missions. The next year found him in Europe, attending the general chapter of the Oblate order in place of the ailing Taché.

Lacombe was transferred in 1874 to the archdiocese of St Boniface so that he could assist Taché in promoting French Canadian colonization. In Winnipeg he became parish priest of St Mary’s parish, superior of St Mary’s residence, and jail chaplain, but his real role, as writer James Grierson MacGregor has remarked, was that of Taché’s man of all work. He went east a number of times to encourage French Canadians and Franco-Americans to settle in the west. He aided the archbishop in attempts to secure an amnesty for the participants in the Red River insurrection, but he refused to help eastern politicians dissuade Louis Riel* from contesting the 1874 federal election in Provencher, Man. In 1879 he was made vicar general of St Boniface and later that year he again represented Taché at the general chapter of the Oblates. (During this trip he was mortified to discover that his wallet had been stolen while he was attending mass at St Peter’s Basilica.) The next year he assumed responsibility for ministering to railway workers along a section of the transcontinental line being built east of Winnipeg, and in the camps he found that blasphemy, drunkenness, and immorality were rife. “My God, send me back to my old Indian mission,” he wrote in his diary.

In the meantime Bishop Vital-Justin Grandin* of St Albert sought Lacombe’s return to that diocese because the status of the Indian missions was in the balance. In the north, Saint-Paul-des-Cris had been abandoned, while in the south, Constantine Michael Scollen had deserted the Blackfoot missions. Taché was reluctant to lose Lacombe, whose services and advice he valued highly, but eventually he deferred to the decision of the superior general of the Oblates and Lacombe went back to St Albert in 1882. He was made superior of its Calgary district and served as parish priest of St Mary’s parish, Calgary, in 1883.

The Canadian Pacific Railway consulted Lacombe on selecting the most suitable route for some of its lines. In 1883 he used his influence to prevent a confrontation between native people and CPR surveyors staking out the railway right of way near Blackfoot Crossing. Through Crowfoot [Isapo-muxika*] Lacombe convoked a meeting of Blackfoot chiefs, provided them with ample sugar, tobacco, tea, and flour, and told them that Lieutenant Governor Edgar Dewdney would listen to their grievances. The Indians were reassured and allowed the surveyors to continue. The railway was grateful for Lacombe’s assistance and, in a special ceremony in a railway car travelling between Calgary and Blackfoot Crossing, he was named president of the syndicate for one hour. He was also given a lifetime pass on the line and other privileges by the company’s directors, who contributed generously to his many projects.

A report to the federal government in 1879 by Nicholas Flood Davin* had recommended that Canada try establishing industrial schools for native children as the Americans had done. Along with Bishop Grandin, Lacombe was the architect of a proposal, probably formulated in 1882, to provide Plains Indian children with vocational instruction under Catholic supervision. Likely in the winter of 1883–84, Grandin sent him to Ottawa to negotiate with the federal authorities in the matter. Lacombe selected the site for St Joseph’s Industrial School at Dunbow (Alta) and served as principal from its opening in 1884 until 1885. The first students, a group of teenage boys, so actively resisted the behavioural norms expected of them that Lacombe was later to recall, “You could open the doors and look inside and see – Hell that first winter.” He would sit on the Board of Education of the North-West Territories from 1886 to 1892.

During the North-West rebellion of 1885 both territorial and federal officials requested Lacombe to visit the Cree and Blackfoot and persuade them not to support Louis Riel. Lacombe travelled to the Blackfoot Indian Reserve, whose residents seemed disinclined to take up arms alongside their old enemies, and then hurried north to call for peace on the Cree reserves near the Battle River. When the hostilities were over he made recommendations to remedy Indian grievances and was asked by Ottawa to investigate matters concerning Indians. To reward those chiefs who had remained loyal during the uprising, the government invited them to visit eastern Canada. Lacombe organized the trip in 1886 for the nine western chiefs, including Crowfoot, and he and interpreter Jean L’ Heureux accompanied them.

Lacombe is said to have been the parish priest at Fort Macleod (Alta) from 1887 to 1889. By 1890, weary of travelling and public life, he determined to spend his remaining days as a hermit at Pincher Creek, where he built the Ermitage Saint-Michel. But his services could not be dispensed with and he was more often a traveller than a hermit. In 1892, for example, he was asked to organize an excursion of eastern prelates and priests from Montreal to Vancouver. At his request the CPR placed a first-class Pullman car at the disposal of the clergy. The tour’s final destination was Mission (Mission City), B.C., where Bishop Paul Durieu* had arranged a Eucharistic congress for the province’s Catholic Indians. By 1893 he was back at Pincher Creek, “alone on the top of my hill with my dog and my cat again,” as he wrote to a colleague.

Early in 1894, however, Lacombe returned to St Boniface to help Taché secure a restoration of the educational privileges for Manitoba’s Catholic minority that Premier Thomas Greenway*’s government had removed. Taché was gravely ill, and it was Lacombe who went to Montreal to oversee publication of a memorial on the subject by the archbishop. He was made priest of St Joachim’s parish at Edmonton in July but his involvement in the school question was not over. Late in 1895 he was sent east by Taché’s successor, Archbishop Adélard Langevin, to speak to members of the Catholic hierarchy and politicians concerning the Conservative government’s attempt to restore the school privileges through remedial legislation. Between December 1895 and March 1896 Lacombe negotiated with Prime Minister Sir Mackenzie Bowell, opposition leader Wilfrid Laurier, and Quebec politicians. As his mission progressed, he was forced by circumstances to support the details of the proposed legislation and to become the government’s intermediary with the hierarchy, which opposed certain of its terms. A private letter written to Laurier insisting that the Liberals support the remedial bill and refrain from proposing a commission of inquiry was published in the Montreal newspaper La Presse. For his part, Laurier complained that Lacombe had compromised himself and presented the Liberals with an ultimatum to support remedial legislation or face the censure of the bishops. As a result of Lacombe’s efforts, the hierarchy and Langevin accepted the remedial bill, despite their earlier opposition to its terms. Of all the missions accepted by Lacombe, this was the one that most taxed his talents, and the intricacies of party politics made him long for the seclusion of his hermitage.

During the 1890s he had other, lesser tasks as well. He was given charge of travel arrangements for the bishops and priests who would attend Archbishop Langevin’s consecration in March 1895. In 1895 also, he was invited to accompany the mayor of Edmonton to Ottawa so that they could lobby the government for construction of a bridge across the North Saskatchewan River to link Edmonton with the railway. (Their efforts produced promises, but the bridge was not built until 1913.) His appointment at Edmonton ended in 1897 and he returned to Pincher Creek. His solitude was interrupted again the next year by the construction of the CPR’s line through the Crowsnest Pass, and once more he ministered to construction gangs. He then went east on a fund-raising tour. In the spring of 1899 he headed out with the commission that was preparing to negotiate Treaty No.8 with the native people of what is now northern Alberta and adjacent areas [see Mostos; James Andrew Joseph McKenna]. Although he joined in efforts to persuade the Métis of the region, whose claims were being settled at the same time, that they should accept their compensation in scrip that was non-transferable, they rejected that initiative.

Lacombe had given much thought to the future of the Métis. In his early years at the hermitage he had begun to lay the groundwork for a project to promote their welfare, and in 1895 he had submitted a request to the federal government to provide four townships for a Métis community. After obtaining the land, Lacombe issued an invitation to the Métis of the Canadian west and Montana to come and settle in the colony, which became known as Saint-Paul-des-Métis (St Paul). Direction of the project was assumed by Adéodat Thérien and a boarding-school was opened in 1897. Despite Lacombe’s efforts to raise money for the colony, its finances were always precarious and this situation discouraged the Métis. In 1905 disgruntled students would set fire to the school and the colony never recovered from the loss. It was dissolved in 1909 and the region opened to French Canadian settlers.

Meanwhile, in 1900 Lacombe was sent to Europe by bishops Grandin, Langevin, and Albert Pascal in the interests of Ruthenian immigrants of the Eastern rite who were living in western Canada. Lacombe’s main preoccupation was to secure the services of Ruthenian clergy and religious communities. He made his needs known to the Oblate superior general, Pope Leo XIII, and Austrian emperor Francis Joseph I. During this voyage Lacombe visited Belgium three times to promote immigration to western Canada, to find a female religious order that would assume responsibility for the boarding-school at Saint-Paul-des-Métis, and to recruit male teaching orders for diocesan schools. He was parish priest of St Mary’s, Calgary, again in 1902–3, but in 1904 he crossed the ocean once more, accompanying Langevin on a tour of Europe and the Holy Land. Lacombe spoke in various centres and collected moneys for the missions and institutions of western Canada.

Near the turn of the century Lacombe’s superiors had encouraged him to write his memoirs since he had served 50 years as a missionary and had been associated with some of the most momentous developments in the history of the region. He began compiling material in 1899 but complained that he constantly was being disturbed. His efforts resulted only in an incomplete account of his activities to 1864. In 1904 he approached Katherine Angelina Hughes*, who was then on staff at the Daily Edmonton Bulletin, and proposed that she write his memoirs, but it was only in 1907 that she agreed to spend some time in Pincher Creek to go over the material he had prepared and consult with him. Two years later Hughes was experiencing difficulty in finishing the project and Lacombe urged her to find someone else to complete it because there were suggestions that the book be presented to him that year during the diamond jubilee of his ordination. Hughes continued the work, however, with Lacombe’s close collaboration. In the spring of 1911 he was concerned that changes had been made to “our book” without his being consulted and, furthermore, that half of the material had been removed to satisfy the demands of a New York publisher. He threatened to prepare a French-language version to set the record straight in the province of Quebec. The book came out in English later that year and it apparently satisfied him. Although Hughes may have thrown humility to the winds in her depiction of Lacombe’s character, Father Lacombe, the black-robe voyageur is an accurate factual account of his activities and career.

In 1908 Lacombe had begun to plan his last venture, the establishment at Midnapore of a home for orphans, the elderly, and the handicapped. He obtained the required land from Calgary businessman Patrick Burns*, who had contributed to the Ermitage Saint-Michel, and he persuaded the Sisters of Charity of Providence to build the structure and operate it. Lacombe also toured the province and eastern Canada to raise money for the institution. After meeting him in Edmonton, his old friend Lord Strathcona [Donald A. Smith] donated $10,000. The Lacombe Home was opened on 9 Nov. 1910 and had 40 residents within six months. Lacombe did not forget Jean L’Heureux and would later have him admitted to the institution. In 1911 Lacombe made his last trip to eastern Canada to collect money for his project. He passed away on 12 Dec. 1916 at the home he had founded. A funeral mass was held in St Mary’s Cathedral, Calgary, and the CPR transported his body in a special car to Edmonton and then to St Albert where he was buried next to Bishop Grandin.

As a missionary, Lacombe had demonstrated great ingenuity in developing instructional aids. He transformed the “Catholic ladder,” into “a small masterpiece of pedagogy,” in the words of one author. In his drawings he depicted two paths an individual might follow: that of evil, represented by idolatry, paganism, and the seven capital sins, and that of righteousness, exemplified by the Old and New testaments and the virtues and sacraments of the Roman Catholic Church. His other contributions to apostolic pedagogy were an illustrated catechism in the Cree language and an illustrated catechism for instructing Indians. The Cree catechism was more detailed than Lacombe’s ladder and was meant to be used by those who were familiar with the rudiments of the Catholic faith. In 1874 Lacombe published a dictionary and grammar of the Cree language that was widely used by other Oblates. He prepared the manuscript of a French-Blackfoot dictionary and collaborated with Émile-Joseph Legal to compile a Blackfoot, Blood, and Peigan vocabulary. He also did new editions of Frederic Baraga*’s Ojibwa grammar and dictionary, translated the New Testament and numerous hymns into Cree, and published instructions and sermons in that language.

Lacombe was in some ways the archetype of the Oblate missionaries who served in western and northern Canada. What made him stand out from the others was his great love of travel and adventure, the degree of his dedication to the Indians and Métis, and his ability to relate to everyone he met. Lacombe was at home in the midst of royalty, bishops and cardinals, white parishioners, or native people. In an age characterized by deep religious and ethnic divisions, he made lasting friendships with numerous English-speaking Protestants. As a missionary, he shared the prejudices of his time vis-à-vis the First Nations; he felt that they had to be civilized, Christianized, and incorporated into the mainstream of the more progressive and capitalistic white community. Nevertheless, he was genuinely concerned for their welfare, and he attempted to improve their material well-being. They understood, and their trust is reflected in the names they bestowed on him. The Cree named him Kamiyoatchakwêt, “the noble soul,” and the Blackfoot called him Aahsosskitsipahpiwa, “the good heart.”

Archival material concerning Albert Lacombe is found in the collections of the Arch. Deschâtelets, Oblats de Marie-Immaculée (Ottawa), the Arch. des Oblats de Marie-Immaculée (Montreal), the Arch. de la Prov. Grandin (St Albert, Alta), the Arch. of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Prov. of Alberta-Saskatchewan (held at the PAA), and the Arch. of the Sisters of Providence (Edmonton).

Grace Ballem, “The Lacombe Home,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 28 (1980), no.3: 1–6. Gaston Carrière, Dictionnaire biographique des oblats de Marie-Immaculée au Canada (4v., Ottawa, 1976–89); “Le père Albert Lacombe, o.m.i., et le Pacifique Canadien,” Rev. de l’univ. d’Ottawa, 37 (1967): 287–321, 510–39, 611–38; 38 (1968): 97–131, 316–50. P. E. Crunican, “Father Lacombe’s strange mission: the Lacombe–Langevin correspondence on the Manitoba school question, 1895–96,” CCHA, Report, 26 (1959): 57–71. P. M. Hanley, History of the Catholic ladder, ed. E. J. Kowrach (Fairfield, Wash., 1993). R.[-J.-A.] Huel, “Jean L’Heureux: canadien errant et prétendu missionnaire auprès des Pieds-Noirs,” in Après dix ans . . . bilan et prospective, sous la direction de Gratien Allaire et al. (Edmonton, 1992), 207–22. K. [A.] Hughes, Father Lacombe, the black-robe voyageur (New York, 1911). J. G. MacGregor, Father Lacombe (Edmonton, 1975).

Cite This Article

Raymond Huel, “LACOMBE, ALBERT,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lacombe_albert_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lacombe_albert_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Raymond Huel |

| Title of Article: | LACOMBE, ALBERT |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 18, 2025 |