Source: Link

LEW, DAVID HUNG CHANG (also known as Lew Hung Chang (Liao Hungxiang in Mandarin), but he frequently signed his correspondence in English David C. Lew), interpreter and legal adviser; b. c. 1886 in China; d. unmarried 23 Sept. 1924 in Vancouver.

At the time of his murder in broad daylight on the streets of Vancouver’s Chinatown, allegedly at the hands of another Chinese, David C. Lew was linked in police reports to the shadowy world of Chinese politics and tong wars. An examination of his life suggests a different picture. Like a handful of other Chinese in Canada, he used his considerable language skills to make a living as an intermediary between Canadian authorities and migrants from China.

Lew likely arrived in Canada when he was 13 or 14. The son of a prominent merchant, he attended public school in British Columbia, where he learned the English language and Canadian customs. His English was apparently excellent. One contemporary newspaper account noted that “to hear him talk one would almost imagine he was a born Canadian.” Lew’s own writings demonstrate a high degree of fluency with only occasional grammatical lapses.

Although he probably qualified as a lawyer, Lew was never able to practise. Members of the British Columbia bar had to appear on the provincial voters’ list and between 1872 and 1947 all those of “Chinese race” were banned from voting in the province. (In 1945 the franchise was extended to those who were serving or who had served in the Canadian military.) As was common among Chinese who had legal training, Lew had a working relationship with a white lawyer, William Wallace Burns McInnes, acting as an interpreter and adviser for Chinese clients. This arrangement allowed him to practise unofficially, but he could not sign official documents or plead in court. He represented clients in a variety of matters. For example, in 1908 he corresponded with a lawyer on behalf of a man who had bought property in Steveston and had been warned by the local chief of police that he would be fined if his tenants engaged in prostitution or gambling. With the lawyer’s assistance, Lew was able to ensure that his client would not be liable for his tenants’ actions. Lew also acted as a court interpreter in British Columbia and other provinces and assisted in police investigations. In 1909 he explained to police chief John C. McRae of Winnipeg, after a member of that city’s Chinese community had been murdered, that “there is very little chance of doing much without some fearless and independent interpreter.” In 1924 Lew would act as legal representative for Wong Foon Sing, the houseboy suspected of having murdered nursemaid Janet Kennedy Smith.

Lew was not above using his role as a go-between for personal gain. A promissory note written in 1908 indicates that he was prepared to pay $1,500 in “legal fees” if he were appointed interpreter for the customs and immigration office in the port of Vancouver. Two other letters suggest that he was involved in a scheme with lawyer Joseph Ambrose Russell, mp Robert George Macpherson, and another person (likely merchant Robert Kelly) to move Chinese through the port in return for $100 per person. The scheme may have involved the use of falsified documents to identify the immigrants as merchants or students, categories exempt from the $500 head tax then applicable.

In 1910–11 Lew’s role as a middleman put him at the centre of a controversy. During his testimony before the royal commission appointed to investigate alleged Chinese frauds and opium smuggling on the Pacific coast, presided over by judge Denis Murphy, Lew claimed that he was the instigator of the inquiry. He stated that he had first expressed his concerns about immigration frauds to the deputy minister of labour, William Lyon Mackenzie King*, in 1908 and that he had also supplied information to lawyer Thomas Robert Edward MacInnes, who was employed by the federal government to advise it on immigration legislation. In June 1910, apparently at his own expense, Lew had gone to Ottawa to present his allegations to the deputy minister of trade and commerce and chief controller of Chinese immigration, Francis Charles Trench O’Hara. Lew charged that the Chinese interpreter for the immigration authorities at Vancouver, Yip On, was part of an immigrant smuggling ring. According to Lew, Yip received payments from people with fraudulent papers and translated their answers to questions from immigration officials in such a way as to allay suspicion. The star witness at the inquiry, he testified that he and federal officials had boarded a ship coming to Vancouver and had tricked passengers into handing over letters about the scheme intended for Yip On. Meanwhile, Yip On’s lawyers claimed that their client was the victim of a conspiracy by Lew and his associates, who were the ones involved in a smuggling scheme. Their accusations may have been correct. Justice Murphy identified Lew as an associate of Chang Toy, the passenger agent for the Blue Funnel Line. Chang was an intense rival of Yip Sang, the passenger agent for the Canadian Pacific Railway’s steamship line and an uncle of Yip On. A letter to O’Hara from Methodist missionary Tom Chue Thom dated 1910 was produced before the commission. It described a serious conflict in Vancouver’s Chinatown between two competing factions, one of which included Lew. Thom described Lew as “Not a Moral man,” but also stated that “he do Good service to your Government which no other Chinaman dare to do it.” Murphy found that Lew and his non-Chinese associates had engaged in “an intrigue . . . to establish some sort of connection with the administration of the Chinese Restriction Act at the Port of Vancouver by obtaining control of the position of Chinese interpreter, and possibly in other ways. Its object to serve some personal advantage.” Murphy did not have sufficient evidence to recommend criminal charges against Lew, although he did recommend them against Yip On. He justified the commission’s reliance on Lew, noting that “the Chinese communities at the coast constitute an imperium in imperio, and it is hopeless for white people to attempt to obtain information of value . . . unless the co-operation of at least one well informed Chinaman can be secured. Mr. Lew was the only such person willing to assist so far as the Commission was aware. . . . In justice to him it must be said that he rendered much valuable aid.”

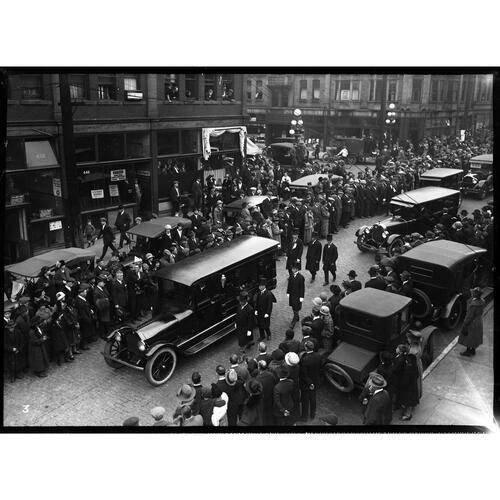

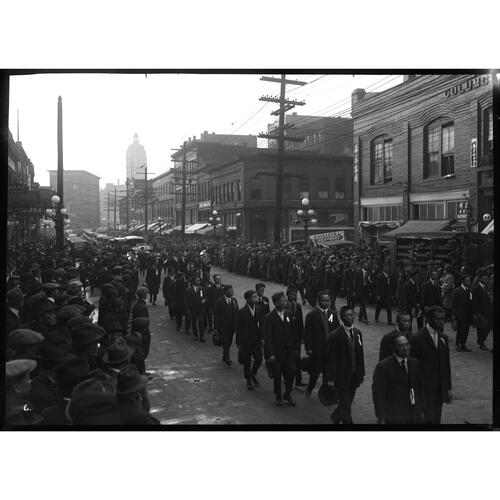

Lew’s work for the police and other authorities may have made him powerful enemies within the Chinese community and could well have caused his death. After he was shot, newspapers reported that the police were carefully watching the tongs in Chinatown and were going to observe his funeral closely. The police linked Lew to what they described as competition between different tongs over gambling revenues. Modern scholarship suggests that the concern over tong wars was exaggerated. In the racially divided world of British Columbia, the police could have known of such activities only by relying on go-betweens and, as Lew’s personal history suggests, go-betweens were not simply neutral interpreters; they had interests of their own. His murderer was never found.

BCA, E/D/L58; GR-1415, file 09847; GR-2951, no.1924-09-331092 (mfm.). Regina Standard, 21 Feb. 1906. Vancouver Daily Province, 11 Jan. 1911, 25 Oct. 1924. Vancouver Daily World, 7, 12 Jan. 1911. Vancouver Morning Sun, 25 Sept. 1924. K. J. Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown: racial discourse in Canada, 1875–1980 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1991). Can., Royal commission appointed to investigate alleged Chinese frauds and opium smuggling on the Pacific coast, Report (Ottawa, 1913). Harry Con et al., From China to Canada: a history of the Chinese communities in Canada, ed. Edgar Wickberg (Toronto, 1982; repr. 1988). L. E. A. Ma, Revolutionaries, monarchists, and Chinatowns: Chinese politics in the Americas and the 1911 revolution (Honolulu, 1990).

Cite This Article

Timothy J. Stanley, “LEW, DAVID HUNG CHANG (Lew Hung Chang (Liao Hungxiang), David C. Lew),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lew_david_hung_chang_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lew_david_hung_chang_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Timothy J. Stanley |

| Title of Article: | LEW, DAVID HUNG CHANG (Lew Hung Chang (Liao Hungxiang), David C. Lew) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | February 19, 2026 |