Source: Link

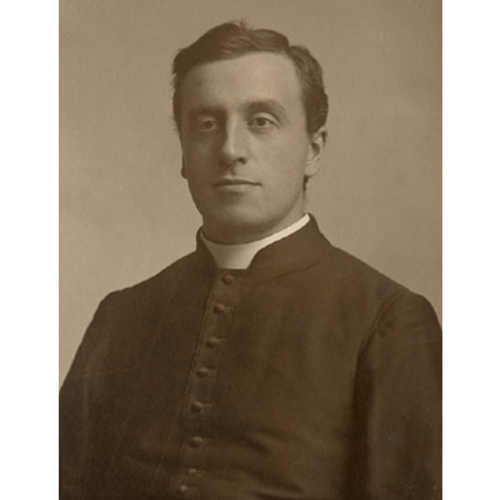

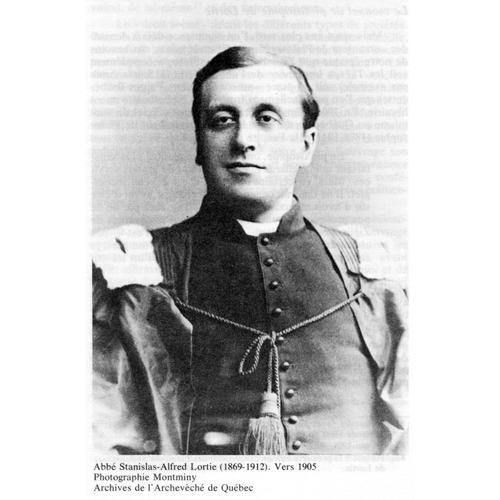

LORTIE, STANISLAS-ALFRED, Roman Catholic priest, professor, and author; b. 12 Nov. 1869 at Quebec, son of Henri Lortie, a merchant, and Marie-Ursule Drolet; d. 19 Aug. 1912 in Curran, Ont., and was buried 22 August at Quebec.

After primary school Stanislas-Alfred Lortie was enrolled in 1881 as a day pupil at the Petit Séminaire de Québec, where he made friends with François-Xavier-Jules Dorion* and Adjutor Rivard*. His quick intelligence and unusual capacity for hard work attracted the attention of his teachers. At the Grand Séminaire de Québec, which he entered in 1889 after completing the classical program, Lortie studied with Abbé Louis-Adolphe Pâquet*, who would become, as it were, his mentor. Sent to further his education in Rome, he spent two years there, specializing in theology at the college of the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda, where theologians were engaged in reviving Thomism. Among his colleagues were Abbé Eugène Lapointe, who would leave his mark on social action in the Saguenay, Abbé Aristide Magnan, a future historian of the Franco-Americans, and Abbé Élie-Joseph-Arthur Auclair, author of several monographs on regional history.

Ordained priest in Rome in June 1892, Lortie returned to Quebec with a doctorate in theology and was appointed to the Petit Séminaire de Québec, where he taught the final part of the classical program (Philosophy) for seven years. His former pupil Abbé Arthur Maheux* recalled that the students particularly appreciated Lortie’s clear explanations, direct and sometimes blunt style, firm reasoning, and resonant voice. In his classes Lortie used a philosophy textbook by a Dominican living in Rome, Thomas-Marie Zigliara, an orthodox but prolix work which was not sufficiently up to date on contemporary questions. In 1900 he was summoned to teach theology at the Grand Séminaire de Québec, a task that remained his chief responsibility until his death.

In addition to teaching and correcting papers, Lortie found time to draft a complete course in philosophy, which would be published in three volumes at Quebec in 1909 and 1910. In keeping with the current instructions from Rome, it was written in Latin, in relatively plain language, under the title Elementa philosophiæ christianæ ad mentem s. Thomæ Aquinatis exposita. It was the first philosophy textbook to be written by a French Canadian for his young compatriots since the one by Jérôme Demers*, published in 1835 and long outdated by the revival of Thomism. Despite its arid syllogistic formulation in dog-Latin and a few relatively weak arguments, the work was received favourably by teachers in the classical colleges who had little pedagogical training and limited time for course preparation. Lortie’s expositions on such social issues as the natural right of workers to unite, or the splendour and failings of parliamentary government, were particularly appreciated. His textbook would remain in use in the Philosophy program until the late 1930s.

Lortie had been raised in an urban setting, where he could observe the lives of the working class, and he had been in Rome as a student and cleric just after the release of the encyclical Rerum novarum, which dealt with the workers’ condition. As a philosopher and theologian, he would make social issues a principal focus of his reflection. François-Xavier-Jules Dorion liked to trace both his own and Lortie’s social vocation back to 1888, when as students at the Petit Séminaire de Québec they had attended a lecture by François-Edme Rameau de Saint-Père, a Catholic economist and disciple of Frédéric Le Play. The hierarchy of Quebec City reached a turning-point on the working-class question in 1900, during a sensational strike in the shoe industry. Taking action that was noted and commented upon within the Catholic world and far beyond in circles concerned by these questions, workers and employers managed to break their deadlock through the arbitration of Archbishop Louis-Nazaire Bégin*. Lortie had followed the proceedings closely and had prepared the draft settlement, which was revised by the archbishop. The notes he made on his reading in these years show that he was watching attentively what was then called the social movement, particularly its development in Europe. In 1900 and 1901 he gave a series of public lectures on socialism at the Université Laval. Lortie could inform and interest the city’s small cultural élite, but what he had to say, the fruit of personal experience and knowledge of European thinking, did not always address his listeners’ concerns. A tireless researcher, in 1903 he wrote a detailed monograph on a working-class family of Quebec City. It came out in Les ouvriers des deux mondes in Paris the following year under the title “Compositeur typographe de Québec.” Accurate and highly informative, this study constitutes an invaluable source on the condition of workers and their families at the turn of the century.

In 1905 Lortie, who belonged to the Société d’Économie Sociale of Paris, founded the Société d’Économie Politique et Sociale de Québec at the Université Laval. On 7 April 1905 Lortie and Joseph-Évariste Prince, a professor at the university, launched an appeal to those who wished to examine social and economic questions seriously. The study group formed in response by a handful of professional people, clerics, and journalists rapidly reached the point where it turned from the situation in Europe to realities in Quebec, which its members set about discussing with the participation of representatives from the shoe industry’s union. The group did not outlast Lortie.

In keeping with the spirit of the time, Lortie gradually developed a plan to set up a large coordinating agency for all Catholic social services in the diocese of Quebec. With Abbé Paul-Eugène Roy*, Abbé Charles-Octave Gagnon, and lawyer Adjutor Rivard he worked out the details of this project. On 31 March 1907, in a famous pastoral letter, Archbishop Bégin of Quebec simultaneously launched the Action Sociale Catholique and set up the Œuvre de la Presse Catholique. The aim was to found a Catholic daily newspaper at Quebec that would be both free of any control by political parties and loyal to the church. It was again Lortie who, with Abbé Roy, persuaded his friend François-Xavier-Jules Dorion to become founding editor of L’Action sociale, which was first issued on 21 Dec. 1907.

Catholic social action also encompassed the temperance struggle, which was a priority of the episcopate after 1900. Lortie had a survey of working-class savings carried out in the banking institutions. From it he concluded that temperance and thrift went together, given that deposits had increased appreciably during the three years (1906–8) of the great temperance campaigns. His report on the survey was considered an excellent contribution to the proceedings of the diocese’s first congress on temperance, which were published in 1910. As well as being an organizer of the congress, Lortie was a founder of Le Croisé, the organ of Action Sociale Catholique, which first came out in September 1910 at Quebec.

Wherever his talents could be put to use, Lortie was there. For instance he served as deputy secretary to the Plenary Council at Quebec in 1909. This first meeting of all Canadian prelates marked their creation of a common front on national and social questions. Lortie also found time to teach at the Collège Jésus-Marie in Sillery. He exercised his ministry as well at the Hôpital de la Miséricorde, a shelter for unmarried mothers.

Lortie lived in the period when a ground swell of French Canadian nationalism was set off by the execution of Louis Riel*. Although he deliberately remained aloof from political parties and worked on social issues rather than on nationalist ones, he nevertheless made an outstanding contribution to consolidating French Canadian identity by founding the Société du Parler Français au Canada with his friend Adjutor Rivard in 1902. Through his enthusiasm, his presentations, and his scholarly writings he became a driving force in this organization. He was one of the editors of the Bulletin du parler français au Canada (Québec), which the society published until 1918 to circulate the work of its members. Lortie’s study on the geographical and linguistic origins of the settlers of New France would remain a classic until quite recently, and his contribution to the card file from which the famous Glossaire du parler français au Canada was drawn in 1930 proved invaluable. He can be credited with having launched on a long-term basis the study of Quebec French conducted according to the scientific principles of the day. His work for the cause of French culminated in the first large congress dealing with the language, which was held at Quebec in 1912.

Modelled on a Eucharistic congress, this gathering consisted of learned meetings alternating with public events; it brought together representatives from France and delegates from all the francophone regions of North America. Their papers described the situation of the minorities and the rights to which they could lay claim, and endeavoured to define the characteristics of French Canadian speech. Public events – the unveiling of the monument to Honoré Mercier*, the Saint-Jean-Baptiste day parade, the official banquets – took on an air of national pilgrimage to the sources of French culture in America. The delegates established a central secretariat, the forerunner of the present-day Conseil de la Vie Française en Amérique, which in the course of time would become an instrument for supporting the survival of francophone minorities.

Nature had endowed Lortie with the vigorous constitution that bespeaks energy. With his broad forehead, sharp eyes, and determined gait he had all that was needed to inspire respect. A true scholar, he excelled in group discussions rather than on the platform or in the pulpit. Outwardly he was a little brusque and his manners were somewhat rough, but he was a master at securing the cooperation of others. He was able to achieve so much in a brief career because he had an unusual flair for organization. Everything he collected, from file cards on French Canadian speech to notes on his readings about the rise of socialism in Germany, was filed away for use at the proper time. Lortie was an original and persuasive thinker, an initiator of projects who was quite happy to serve as secretary or treasurer and would carry out his duties faithfully and conscientiously.

As for the ideas inspiring his actions, Lortie was an outstanding example of the intellectual clerics who reached adulthood at the time of Rerum novarum and Pius X’s subsequent crusade to rechristianize society. Lortie adapted just as readily to the new spirit of French Canadian nationalism. His commitment to the fight against intemperance and his endeavours in favour of the Catholic press fitted into the logic of “social combat.” Admittedly, Lortie’s activity and thought bore the signs of the élitism and clericalism of his era. He no doubt quickly assessed the limits to his support for workers’ action, which he viewed in the somewhat paternalistic manner of major French Catholic employers such as Léon Harmel. Lortie was obviously also more at ease with his former classmates, who spoke his language, than with “the people,” from whom he was separated by virtue of being a priest and university professor. He differed from his clerical predecessors as much by his more thorough education as by his blunt refusal to participate in partisan political struggles.

At 42 Lortie was already worn down, “long before his time,” by his “feverish activity.” Suffering from the illness that would carry him off, he retired to live with his brother, who was parish priest of the small rural francophone parish of Curran. He passed away there on 19 Aug. 1912. His funeral at the cathedral in Quebec drew all the clerics and laymen involved in nationalist and social issues who were living in the old capital. Abbé Émile Chartier*, a friend following in his footsteps, caught the essence of Lortie’s role: “[He] laid down the principles and the bases of our action. Those whom he inspired, those who helped him, remain to bring his work to fruition and continue the enterprise; they will complete the edifice for which he could only provide the blueprint.”

Stanislas-Alfred Lortie is the author of L’origine et le parler des Canadiens français: études sur l’émigration française au Canada de 1608 à 1700, sur l’état actuel du parler franco-canadien, son histoire et les causes de son évolution (Paris, 1903); “Compositeur typographe de Québec, Canada (Amérique du Nord), salarié à la semaine dans le système des engagements volontaires permanents d’après les renseignements recueillis sur les lieux en 1903,” in Les ouvriers des deux mondes . . . , no.101 (Paris, 1904; reissued in Paysans et ouvriers québecois d’autrefois, introd. de Pierre Savard, Québec, 1968); and Elementa philosophiæ christianæ ad mentem s. Thomæ Aquinatis exposita (3v., Québec, 1909–10).

ANQ-Q, CE1-97, 14 nov. 1869. ASQ, Journal du séminaire; mss, 398, 400, 411; Univ., 56, 304. NA, MG 30, C49, 13. L’Action sociale (Québec), 20 août 1912. E.-J.[-A.] Auclair, “L’abbé Stanislas-Alfred Lortie,” La Semaine religieuse de Montréal, 16 sept. 1912: 190–95. La Semaine religieuse de Québec, 1912–13. Almanach de l’Action sociale catholique (Québec), 1918: 17–18; 1928: 12, 79. Bull. du parler français au Canada (Québec), 11 (1912–13): 7–9. Lionel Groulx, Mes mémoires (4v., Montréal, 1970–74), 1: 195. J. Hamelin et al., La presse québécoise. Yvan Lamonde, La philosophie et son enseignement au Québec (1665–1920) (Montréal, 1980). Premier congrès de la langue française au Canada, Québec, 24–30 juin 1912: compte rendu (Québec, 1913), 663–66. Le séminaire de Québec: documents et biographies, Honorius Provost, édit. (Québec, 1964). Michel Têtu, “Les premiers syndicats catholiques canadiens (1901–1921)” (thèse de phd, univ. Laval, Québec, 1961). Univ. Laval, Annuaire, 1913/14.

Cite This Article

Pierre Savard, “LORTIE, STANISLAS-ALFRED,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 19, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lortie_stanislas_alfred_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lortie_stanislas_alfred_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Pierre Savard |

| Title of Article: | LORTIE, STANISLAS-ALFRED |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | January 19, 2026 |