Source: Link

NAME UNRECORDED, enslaved Black woman; fl. 1802–3 near Fort Malden (Amherstburg), Upper Canada.

During and after the American Revolutionary War, an Irish-born British official named Matthew Elliott enslaved 50 to 60 people. Some were Indigenous; the majority were Black. The names of all but eight of these women, men, and children are unrecorded.

A “Cursed negroe wench”

Among the unnamed individuals was a Black woman whom Elliott sold in about 1802 to Alexander Duff, a fur-trade merchant and co-founder of Sandwich (Windsor), Upper Canada, and his wife, Phillis. The only surviving document attesting to the woman’s existence is a letter sent from one prominent Upper Canadian office holder to another. On 17 May 1803 Alexander Grant informed John Askin: “Mr Duff and Phillis has been for this week past perplexed and Troubled very much with a Cursed negroe wench they bought some time Agoe from Captn Elliott. She and a negro man are both in Goal [gaol] here for thieft.”

Instead of being named, the woman is called a “wench,” a term that, by the late 18th century, had become common to describe enslaved Black females of any age in an objectifying and offensive way. The fact that she is deemed “cursed” suggests that her behaviour was disruptive and she engaged in small acts of resistance (as did Peggy*, a Black woman enslaved by Peter Russell). The manner in which she is described – as merely a nameless possession – exemplifies the systematic and dehumanizing nature of chattel slavery. Nothing more is known about her, but the context of this woman’s bondage can shed light on her circumstances and those of others who endured lives of forced servitude in Upper Canada.

Slavery in Upper Canada

Between 1760 and 1834 there were more than 600 enslaved Black people under British rule in what was known from 1791 as Upper Canada (previously western Quebec); 330 of them were held in the colony’s Western District, where Elliott secured his land grant. (Among them was Jack York*, one of the 14 Black people enslaved by James Girty in Gosfield Township.) The names and sexes of about one-third of the enslaved Black people in Upper Canada do not appear in extant documents; for many, this information may never have been recorded. They were held in hereditary bondage in uneven concentrations across the colony, from the Detroit River to the border with Lower Canada. Slave-holders were primarily, but not exclusively, members of the elite and the governing classes, such as James Baby*, John Butler*, Thomas Fraser*, Robert Isaac Dey Gray, William Jarvis, Solomon Jones*, Koñwatsiˀtsiaiéñni* (Mary Brant), John Walden Meyers*, John Stuart, and Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant). Gradual abolition was introduced in 1793 by An act to prevent the further introduction of slaves, and to limit the term of contracts for servitude within this province, better known as the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada [see Chloe Cooley*]. The practice continued, however, until 1834, when it was abolished by the British parliament.

The movement of these captives was influenced by a number of factors: the broader context of chattel slavery in North America, including the Maritimes [see Name Unrecorded* (fl. 1772–86)]; the expansion of the British empire northwards on the continent following the Seven Years’ War; the American Revolutionary War and subsequent loyalist evacuation; and the gradual abolition of slavery in the northern United States and Upper Canada. After the Seven Years’ War, most of the people enslaved by white settlers in British North America were of African descent, and the number who were Indigenous drastically decreased. There was an especially notable shift in the enslaved population of Quebec, where previously the majority of those held in bondage had been Indigenous and approximately one-third Black. The migration of loyalists northwards after the Revolutionary War resulted in a significant increase in the number of enslaved Black people in the remaining British North American colonies.

The Elliott farm

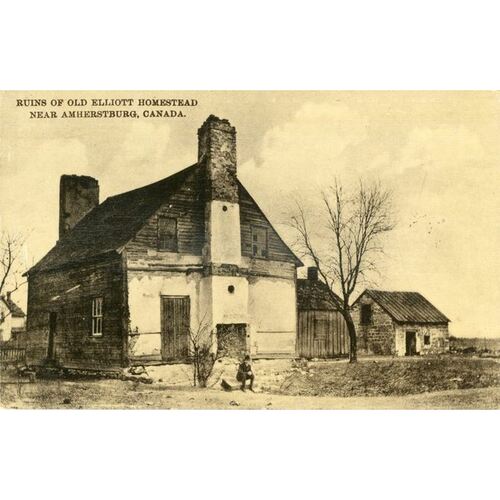

Most of the Black people Matthew Elliott held in bondage were acquired during wartime raids by British forces, before he decamped northwards. They were confiscated from patriots in the Thirteen Colonies, transported to western Quebec, and kept for Elliott’s personal use, supervised on his behalf by an overseer named James Heward. In a 14 May 1797 letter to James Green, the military secretary to Lord Dorchester [Carleton], the British officer Hector McLean wrote of Elliott: “He lives as I am informed in the greatest affluence at an expense of above a thousand a year. He possesses an extensive farm not far from the garrison stock’d with about six or seven hundred head of cattle & I am told employs fifty or sixty persons constantly about his house & farm[,] chiefly slaves.” That farm – really a large plantation on his vast land grant – had been settled by Elliott near Fort Malden. It included what traveller Isaac Weld* described in the late 1790s as a splendid two-storey house on the waterfront of the Detroit River, “the best in the whole district,” adorned with a “neat little lawn.”

The experiences of enslaved Black people were shaped by the intersection of their race and their social and legal status. The women and men on Elliott’s farm would have performed myriad agricultural tasks and domestic chores. Prevailing gender norms were commonly adhered to when assigning responsibilities, but whenever it suited the interests of slave-holders, enslaved women were forced to do “men’s work” and enslaved men had to perform “women’s work.”

Elliott was one of the largest slave-holders in the colony; the average enslaver in Upper Canada held one to three Black people in hereditary bondage. On Elliott’s farm the duties of the enslaved included clearing land, chopping wood, planting and harvesting crops, threshing wheat, tending to the many livestock and the well-groomed garden, and hunting game. Some of the men helped build the palatial house and other buildings on the homestead, including barns, stables, and the cabins they lived in; they also erected fences. House servants, male and female, cleaned, cooked, did laundry, sewed, spun wool and yarn, made soap and candles, and churned butter. They also served the many visitors Elliott entertained in his role as a colonial official and tended to the personal needs of his family. Some tasks were more likely done by women, such as taking care of their enslaver’s children. This forced productivity contributed greatly to Elliott’s personal wealth and comfort for at least 20 years. He had more land under cultivation and owned more horses and cattle than his neighbours, and had crop yields at least five times greater than theirs.

The pursuit of freedom

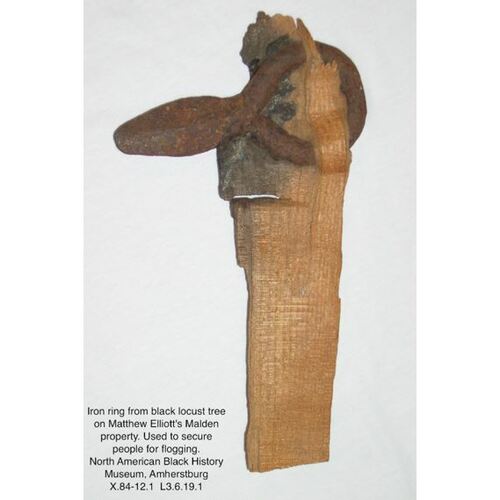

Elliott was known to have treated those he enslaved very harshly. A metal ring was found embedded in a black locust tree on his property, where he evidently had individuals tied to be whipped. It is not surprising, then, that the majority pursued their freedom. First, in 1805, executing what seems to have been a coordinated plan, about 30 of them fled across the Detroit River into Michigan, a free territory. Secondly, in the winter of 1806–7, eight more men and women escaped there. Such clandestine actions indicate the individual and collective agency they exercised. These freedom-seekers may well have been encouraged by a formerly enslaved man named Peter Denison, who had been put in charge of an all-Black militia unit raised by Michigan’s governor, William Hull. The enslaved on both sides of the Detroit River had close social networks and relationships.

Michigan, a territory until it achieved statehood in 1837, had been part of the former Northwest Territory (which also comprised present-day Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota), within which the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had outlawed slavery. The institution was legal in Upper Canada, however, even after the 1793 passage of the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada. That legislation set in motion gradual abolition, but it did not emancipate any enslaved individuals or prevent their sale within Upper Canada or across the American border; it permitted the lifelong enslavement of those held as property at the time of the act’s passage. Consequently, northern American territories and states, and other states that moved towards gradual abolition, became places of possible freedom for Black people who were held in bondage in the colony [see Henry Lewis*]. They sought refuge in the United States decades before African American freedom-seekers pursued their liberty in British North America as part of the movement that became the Underground Railroad.

The significance of identities unknown

Enslaved people were a legal commodity in Upper Canada, and in many cases, including that of the woman Alexander Grant described as a “Cursed negroe wench,” their names are unrecorded. Just eight of the individuals held in bondage by Matthew Elliott have been identified, and that is only because he filed court cases in Michigan in an effort to get them back. The names and sexes of most of those he subjugated have been lost to history, but their determination to be free deserves to be recognized and remembered.

Marsh Hist. Coll. (Amherstburg, Ont.), Assessment for Malden and Amherstburg, 1812–1813. Natasha Henry-Dixon, “One too many: the enslavement of Black people in Upper Canada, 1760–1834” (phd thesis, York Univ., Toronto, 2023). Reginald Horsman, Matthew Elliott, British Indian agent (Detroit, 1964). “J. Grant to J. Green, Amherstburg, 7 Aug. 1807,” in Douglas Brymner, Report on Canadian archives, 1896 (1897), 29 (copy at www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_03505_16/61). The John Askin papers, ed. M. M. Quaife (2v., Detroit, 1928–31), 2 (1796–1820), 388–90. Frank Mackey, Done with slavery: the Black fact in Montreal, 1760–1840 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 2010). “McLean to Green, Amherstburg, 14 Sept. 1797,” in The Windsor border region, Canada’s southernmost frontier: a collection of documents, ed. E. J. Lajeunesse (Toronto, 1960), 221. Michigan Pioneer Coll., XXXVI (1908): 185–86. Tiya Miles, The dawn of Detroit: a chronicle of slavery and freedom in the city of the straits (New York, 2017). R. W. Riddell, “The slave in Canada,” Journal of Negro Hist. (Washington), 5 (1920): 261–377. The statutes of the province of Upper Canada … (Kingston, 1831). Transactions of the Supreme Court of the Territory of Michigan, ed. W. W. Blume (6v., Ann Arbor, Mich., 1935–40), 2: 156, 216, 219. Isaac Weld, Travels through the states of North America, and the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (London, 1799).

Cite This Article

Natasha Henry-Dixon, “NAME UNRECORDED (fl. 1802–3),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/name_unrecorded_1802_3_5E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/name_unrecorded_1802_3_5E.html |

| Author of Article: | Natasha Henry-Dixon |

| Title of Article: | NAME UNRECORDED (fl. 1802–3) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2025 |

| Year of revision: | 2025 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |