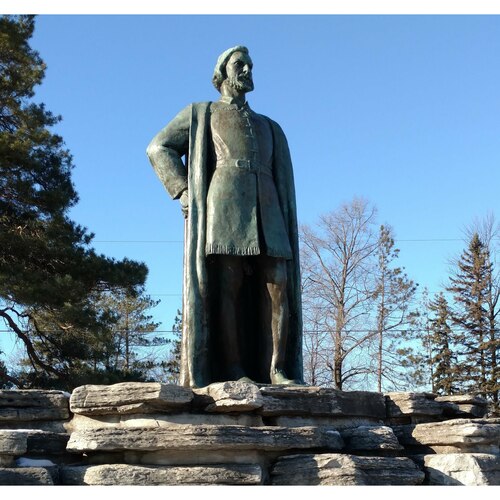

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

NICOLLET DE BELLEBORNE, JEAN, interpreter and clerk of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, liaison officer between the French and the First Nations, explorer; b. c. 1598, probably at Cherbourg (Normandy), son of Thomas Nicollet, king’s postal courier between Cherbourg and Paris, and of Marie de Lamer; drowned near Sillery in 1642.

Nicollet’s arrival in Canada – in the service of the Compagnie des Marchands de Rouen et de Saint-Malo – remains difficult to date. The year 1618 seems likely, though a bill of sale, possibly drawn up in 1619 in France and containing a number of important passages that are illegible due to its state of deterioration, suggests that Nicollet had not arrived in Canada prior to that year. Like Marsolet and Brûlé, he was to live among the indigenous allies in order to learn their languages and customs and explore the regions they inhabited. Nothing is known of his education or temperament, except this remark by Father Vimont in 1643: “his disposition and his excellent memory led one to expect worthwhile things of him.”

Samuel de Champlain, at the time of his explorations, had established relations with the Algonquin in the upper reaches of the Ottawa (Outaouais) River. It is presumed that, in his desire to strengthen the alliance that was only just taking shape, it was Champlain who instructed Nicollet, the year he arrived, to go and spend the winter on Allumette Island. This place was the rallying point of the great Algonquin family commanded by Tessouat (d. 1636). The island was located at a strategic spot on the Ottawa River, the fur-trade route. It was important, for the sake of trade, that the nations living on the shores of the Ottawa should be friendly with the French. Nicollet stayed two years at Allumette Island and carried out his mission very well. He learned the Huron and Algonquin languages, lived the precarious existence of the indigenous people, came to know their customs, and explored the region. They were not long in accepting him as one of their own. They made him a chief, allowed him to attend their councils, and even took him among the Iroquois to negotiate a peace treaty.

Nicollet returned to Quebec in 1620. He made a report on his mission and was given another: to make contact with the Nipissing who lived on the shores of the lake of the same name. Each year the Nipissing were assuming a more important role in the fur trade, acting as intermediaries between the French and the indigenous communities of the west and of Hudson Bay. It was Nicollet’s task to consolidate their alliance with the French, and to see that their furs did not find their way to Hudson Bay.

Nicollet went to the country of the Nipissing and lived among them for nine years. He had his own lodge and a store. By day he traded with members of the various indigenous groups who were on their way to the shores of Lake Nipissing, and questioned them about their country; at night he noted down what he had gleaned. These “mémoires” of Nicollet, unfortunately lost today, have come to us indirectly through the Jesuit Relations. Father Paul Le Jeune, who was able to consult them, drew inspiration from them to describe the customs of the First Nations in that region.

When Quebec was captured by the English in 1629 [see Champlain; Sir David Kirke], Nicollet, who was loyal to France, probably took refuge in the Huron territory and with the Nipissing. He thwarted all the English plans to get the indigenous people to trade with them.

Nicollet appeared on 20 June 1633 at Sainte-Croix, where he met Champlain. He asked permission to set himself up at Trois-Rivières as a clerk of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, and his wish was readily granted. Before taking up his new duties, however, he was asked, no doubt by Champlain, to undertake a voyage of exploration and pacification among the Ounipigons, who according to the Relation of 1640 were also called the “Gens de Mer” or “Puants” (from the translation of the “Algonquin word ouinipeg [which] means eau puante [smelly water]”). An alliance between the Gens de Mer and the Dutch of the Hudson River region was to be feared. It was necessary to restore peace as soon as possible. Nicollet was also supposed to use the trip to check the information he had gathered concerning the China Sea, which according to the First Nations was nearby. Nicollet therefore provided himself, before his departure, with a robe of Chinese damask, adorned with flowers and multi-coloured birds. Despite not being able to date this voyage precisely, it is known that on 3 July 1634 he concluded a service agreement with Théodore Bochart of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés, and that he would return to the colony in 1635.

Nicollet followed the traditional Ottawa River route, branched off at Allumette Island in the direction of Lake Nipissing, and then went down the French River (Rivière des Français) to get to Lake Huron. Along the way he recruited an escort of seven Huron. The rest of the journey remains imprecise. For a long time historians believed that Nicollet headed towards Michilimackinac, entered Lake Michigan, and reached Green Bay. Since Marcel Trudel*’s work, it has been thought that Nicollet went up towards Sault Ste Marie, where he crossed and entered Lake Superior, following its north shore as far as the land of the Gens de Mer. Attired in his damask robe, he momentarily struck terror into the Gens de Mer, who took him for a god and, according to the Relation of 1643, called him “Manitouiriniou, that is to say ... Man of Wonders.” He assembled 4,000 or 5,000 men, grouping together the different nations of the region, and, while smoking their long-stemmed pipes, they concluded a peace settlement. Nicollet had achieved the first objective of his trip. Unfortunately, he had not found the China Sea, although according to the Relation of 1640, he was the Frenchman who “penetrated farthest into these most remote of lands.”

On his return in 1635 Nicollet settled at Trois-Rivières, as a clerk of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés. On 15 August he accepted a new service agreement, this time with Champlain. On 23 May 1637 he and his brother-in-law Olivier Letardif received a grant of 160 acres of wooded land located in what would become the castellany of Coulonge at Quebec [see Louis d’Ailleboust de Coulonge et d’Argentenay]. Moreover, according to a map by Jean Bourdon dated 1641, Nicollet owned, with Letardif and Guillaume Couillard, a concession on the Beaupré shore. In Quebec, around 7 October 1637, he married Marguerite, the daughter of Couillard and Guillemette Hébert, by whom he had a son (who died shortly after birth) and a daughter. The latter, whose first name was Marguerite, became the wife of Jean-Baptiste Legardeur* de Repentigny, a future member of the Conseil Souverain. Until his death Nicollet stood out as a leading figure in the little town of Trois-Rivières. The noteworthy services that he rendered to the colony, along with his knowledge of indigenous languages and customs, earned him the respect of everyone.

The Relations often speak warmly of his exemplary conduct; unlike the majority of the coureurs de bois of his day, Nicollet appears always to have lived according to the principles of his religion. In about 1628, however, he did have an illegitimate daughter, probably born of a Nipissing woman. In the Relation of 1636 Father Le Jeune wrote that Nicollet “often wintered [with the Nipissing], and from whom he never withdrew except to maintain assurance of his salvation by partaking of the Sacraments.” His greatest joy, in the spare moments that his duties allowed him, was to act as an interpreter for the missionaries and to teach religion to the First Nations.

Nicollet died prematurely in 1642. While he was temporarily replacing the head clerk of the company, his brother-in-law Letardif, he was asked to go as quickly as possible to Trois-Rivières to save a Sokoki prisoner the Algonquin were preparing to torture. The shallop that was taking him to Trois-Rivières was overturned near Sillery by a strong gust of wind. Being unable to swim, he drowned. His funeral was held at Quebec on 29 October.

ASQ, Documents Faribault, 7; Registre A, 560f. (carries Nicollet’s signature). Champlain, Œuvres (Laverdière), V, VI. JR (Thwaites), VIII, 247, 257, 267, 295f.; XXIII, 274–82; et passim. C. W. Butterfield, History of the discovery of the north-west by John Nicolet in 1634; with a sketch of his life (Cincinnati, 1881). Godbout, Les pionniers de la région trifluvienne. Auguste Gosselin, Jean Nicolet et le Canada de son temps (Québec, 1905). Lionel Groulx, Notre grande aventure: l’empire français en Amérique du Nord (1535–1760) (Montréal et Paris, [1958]). Gérard Hébert, “Jean Nicolet, le premier blanc à résider au lac Nipissing” (La Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, Documents historiques, XIII, Sudbury, 1947), 8–24. Henri Jouan, “Jean Nicolet (de Cherbourg), interprète-voyageur an Canada, 1618–1642,” RC, XXII (1886), 67–83. Berjamin Sulte, “Jean Nicolet,” Journal de l’Instruction publique, XVII (1873), 166f.: XVIII (1874), 28–32; “Jean Nicolet et la découverte du Wisconsin, 1634,” RC, VI (1910), 148–55, 331–42, 409–20; “Le nom de Nicolet,” BRH, VII (1901), 21–23; “Notes on Jean Nicolet” (Wisconsin Hist. Soc. Coll., VIII, Madison, 1879), 188–94.

Revisions based on:

Bibliothèque et Arch. Nationales du Québec, Centre d’arch. de Québec, CE301-S1, 7 oct. 1637, 29 oct. 1642, 9 juill. 1656; CN301-S131, 22 oct. 1637; CN301-S263, 18 oct. 1643; P600, S4, SS2, D720; P1000, S3, D1517; Centre d’arch. de la Mauricie et du Centre-du-Québec (Trois-Rivières, Québec), CE401-S48, décembre 1640. Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), R6286-0-8. A[lexandre] Alix, Histoire de Jean Nicolet de Hainneville: interprète et explorateur au Canada (1618–1642) (Saint-Lô, France, 1908). D. H. Fischer, Champlain’s dream (New York and Toronto, 2008). Jacques Gagnon, “Jean Nicollet vu par Jean Hamelin et révisé par Marcel Trudel,” Histoire Québec (Montréal), 22 (2016–17), no.4: 27–30; “Note de recherche: Jean Nicollet au lac Michigan, histoire d’une erreur historique,” RHAF, 50 (1996–97): 95–101; “Note de recherche: les Nipissiriniens depuis Jean Nicollet,” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec (Montréal), 45 (2015), no.1: 75–79. JR (Thwaites). Monumenta Novæ Franciæ, Lucien Campeau, édit. (9v., Rome et Québec, 1967–87; Rome et Montréal, 1989–2003), 2 (Établissement à Québec (1616–1634)); 4 (Les grandes épreuves (1638–1640)). Marcel Trudel, Histoire de la Nouvelle-France (6 tomes en 7v., Montréal, 1955–99), v.3 (La Seigneurie des Cent-Associés, 1627–1663), tome 2 (La société, 1983); “Jean Nicollet dans le lac Supérieur et non dans le lac Michigan,” RHAF, 34 (1980–81): 183–96; Le terrier du Saint-Laurent en 1663 (Ottawa, 1973). Denis Vaugeois, “Le vrai rêve de Champlain,” Cap-aux-Diamants (Québec), no.134 (été 2018): 15–20.

Cite This Article

Jean Hamelin, with the collaboration of Jacques Gagnon, “NICOLLET DE BELLEBORNE, JEAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nicollet_de_belleborne_jean_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/nicollet_de_belleborne_jean_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Hamelin, with the collaboration of Jacques Gagnon |

| Title of Article: | NICOLLET DE BELLEBORNE, JEAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 26, 2025 |