Source: Link

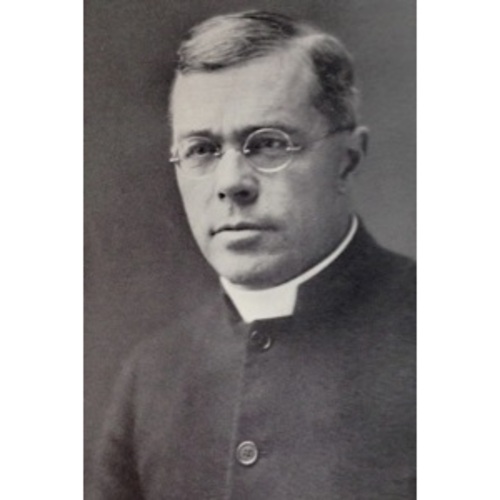

O’GORMAN, JOHN JOSEPH (baptized John Joseph Patrick Gorman), Roman Catholic priest and military chaplain; b. 8 March 1884 in Ottawa, eldest of the three children of John Gorman, a civil servant, and Elizabeth Rose Warnock; d. there 24 April 1933.

John Joseph O’Gorman’s surname at birth was Gorman, but in his youth he would adopt the family’s ancient patronymic. He was educated in St Patrick’s School and then attended the College of Ottawa, where he obtained ba and bphil degrees. Intent on entering the priesthood, he studied in Germany, Belgium, France, and Italy before returning to Canada to enrol at the Grand Séminaire de Montréal. On 21 Dec. 1908 Archbishop Joseph-Thomas Duhamel* ordained O’Gorman in his home parish in Ottawa’s Centretown. He served briefly at St Brigid’s in the city’s largely Irish Lower Town district before the archbishop sent him to pursue further studies in Rome, where he earned a doctorate in canon law. He was widely read and had a command of seven languages besides English: he learned Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Gaelic. After returning to Canada in about 1911 he was appointed to St Philip’s congregation in Richmond, Ont., and in March 1913 was transferred to the fledgling Blessed Sacrament parish in the Glebe neighbourhood of Ottawa. Except for the period when he was abroad during World War I, he would remain there for the rest of his life, building the church’s social, liturgical, and educational foundations.

As an advocate of Catholic separate schools in which English was the language of instruction, O’Gorman became a bête noire to leaders of Ottawa’s French Catholic community. He consistently challenged what he deemed to be French control of the separate-school board [see Samuel McCallum Genest; Duhamel], and in a lengthy article in the Ottawa Citizen (10 March 1914) he emphatically opposed the retention of bilingual schools within the board’s jurisdiction: “The present insurrectionist attitude of French trustees jeopardizes the whole separate school system.… Let the bi-lingual schools be separated from the separate school system to which they are foreign, and let them be supported by the school taxes of those who wish to become bi-lingual school supporters.”

He even took aim at his alma mater, claiming that the loss of eight anglophone Oblate priests from the teaching staff made the College of Ottawa less attractive to English-speaking Catholics. He enthusiastically battled with Le Droit, the local French daily, which attacked him as anti-French Canadian. There were heated exchanges with Franco-Ontarian educational leaders over the separate-school board’s violation of Regulation 17, passed by Sir James Pliny Whitney*’s government, which prohibited teaching in French beyond the first two years of schooling. Archbishop Charles Hugh Gauthier* forbade O’Gorman and his principal antagonist, the Reverend Pierre-Siméon Hudon, dit Beaulieu, of Rockland, from addressing “religio-racial questions” in the press.

When World War I erupted in August 1914, O’Gorman emerged as an ardent supporter of the Canadian and imperial war efforts. From his pulpit and in print, O’Gorman was able to weave participation of Irish Canadian Catholics into an assertion that, from the time of the South African War, whenever the British empire had called, Canada’s Irish Catholics had answered robustly. In the first months of the conflict his speeches reached a national audience in the Catholic press. After a joint pastoral letter was issued in October 1914 by the archbishops of Quebec, Montreal, and Ottawa (which was endorsed by other clergy, including archbishops Timothy Casey of Vancouver and, the following year, Alfred Arthur Sinnott* of Winnipeg), O’Gorman delivered a powerful sermon, reiterating the points made by these leading metropolitans about the need for Catholics to do their part as British subjects. He claimed that it was not just a patriotic duty to “fight with the Empire,” but also a religious duty, a constant theme in his rhetoric throughout the war. His views infuriated Henri Bourassa*, the editor of Montreal’s Le Devoir, who wrote to Gauthier to protest what he considered to be historical and theological falsehoods perpetrated by a priest of Gauthier’s diocese. The archbishop permitted O’Gorman to respond, which he did, repudiating Bourassa point by point on the historical issues and then accusing him of a veiled attack on the pastoral letter and its authors. O’Gorman continued speaking and writing on the war throughout 1915, a course of action that would culminate in a document based on a series of sermons that he intended to publish under the title “Render unto Caesar.” Shortly after he preached the final sermon on 2 Jan. 1916, he submitted the text to Gauthier for his imprimatur. Gauthier refused, stating that the diocesan censor had found it to contain “unsound moral doctrine.” Undaunted, O’Gorman edited the text, and it would soon appear as Canadians to arms! under the imprimatur of Neil McNeil, archbishop of Toronto.

Later in January, with Gauthier’s blessing (and perhaps to his relief), O’Gorman enlisted in the Canadian Chaplain Service (CCS) through the 199th Infantry Battalion (Irish-Canadian Rangers), based in Montreal. He was appointed its honorary captain in early February, when it was reorganized as the 199th Infantry Battalion (Irish-Canadian Rangers). In March he sailed for England with a letter of introduction from the minister of militia and defence, Sir Samuel Hughes*, and was assigned to the Duchess of Connaught’s Canadian Red Cross Hospital at Taplow. In September 1916, while serving as an honorary major with the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Division, O’Gorman assisted in evacuating wounded soldiers from no man’s land. While helping to carry one of the injured he was struck by shrapnel from a German whiz-bang. The hot metal tore into his legs and shattered his left shoulder, elbow, and wrist. He was transported to England through the hospital network that he had once served. Racked by pain, he suffered repeated infections and came close to having his arm amputated.

The Canadian Expeditionary Force demobilized O’Gorman and sent him to Canada for further treatment in December 1916. While convalescing at the Ottawa General Hospital under the care of the Sisters of Charity of Ottawa, O’Gorman regained partial use of his arm and began pursuing a new initiative and a return to the European theatre of the war. In cooperation with the Knights of Columbus throughout Canada, he established the Catholic Army Huts Association to erect recreational, spiritual, and social facilities for all Canadian military personnel in England and France regardless of their religion. On 26 Nov. 1917 he sailed for England on special duty as the association’s secretary-treasurer. Based in London, he coordinated fund-raising and building projects. Under his leadership, in 1917 and 1918 more than $1 million was collected from both Catholics and Protestants in what proved to be an unprecedented ecumenical effort on behalf of troops overseas. For O’Gorman and others, the Catholic Army Huts initiative was a public affirmation of Catholic dedication to and support for the imperial war effort despite the conscription crisis [see Sir Robert Laird Borden] that was raging in the midst of the campaign.

O’Gorman had also used his convalescence in Ottawa to wade deeply into the controversy plaguing the CCS itself. He was able to alert cabinet members – particularly justice minister Charles Joseph Doherty, and, through him, the new minister of militia and defence, Sir Albert Edward Kemp*, and the prime minister – to problems involving the recruitment and allocation of Catholic chaplains and their treatment by Protestant commanding officers. O’Gorman gainsaid the positive reports of Alfred Edward Burke*, who was passing himself off as the senior Catholic chaplain and who claimed there were no issues in his section of the CCS. O’Gorman also undercut Richard Henry Steacy, an Anglican who had been appointed senior chaplain and who was an ally of Samuel Hughes, stating that Steacy discriminated against Catholics by being indifferent to their concerns and complaints. O’Gorman and Steacy had a rather rocky past; in the weeks before O’Gorman was wounded on the battlefield, he and Father Wolstan Thomas Workman had led a Catholic revolt against Burke, a loyal supporter of both Steacy and Hughes. O’Gorman believed that the service needed a shake-up: a new director who was Protestant (and not an Orangeman) and an assistant director who would be in charge of the Catholic branch. By March 1917 O’Gorman, who also had connections with fellow Ottawan Sir George Halsey Perley, the acting Canadian high commissioner in London and head of the new Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces, had won the argument. Colonel John Macpherson Almond, an Anglican and a veteran of the South African War, had replaced Steacy as director on 15 February, and soon afterwards Workman became the assistant director for Roman Catholics. In early January 1919 O’Gorman would be promoted CCS deputy assistant director in charge of lines of communication in France.

O’Gorman’s most poignant articulation of what he saw as the balancing of identities between Protestants and Catholics during the chaos of World War I and in the aftermath of the 1916 Easter rising against British rule in Ireland was made in a speech delivered during St Patrick’s Day celebrations in 1917, in which he described British imperialism towards Canada as “the nation-fostering, not nation-destroying type.” He addressed the Irish Home Rule question directly and unequivocally:

The interests of Canada, as a nation, as an autonomous part of the British Empire, and as a member of the world’s family of nations, demanded that we should enter this war against the Turco-Teutons, and that having entered it, we should prosecute it till we finish it or it finishes us. The few voices that are raised here and there, asking that we should halt till Ireland gets Home Rule, have rightly been disregarded by the vast majority of Irish Canadians. We do not intend to do wrong that good may come. We were second to none in 1914, and 1915 and 1916, in the sincerity of our loyalty, and the greatness of our sacrifices, and we will be second to none in 1917.

Nevertheless, O’Gorman was highly critical of British policy in Ireland since the rising, claiming that Ireland was due the dominion status that was already a fact in Canada and Australia. He maintained that Irish Canadians, motivated by the same spirit in which they had pursued the war, would demand justice for the Irish people, declaring that “the policy adopted by Irish Canadians to fight Germans on the field of battle and British junkers in the council chamber of the Empire, is one which fulfils our duties as the sons of Irishmen and the sons of Canada.” O’Gorman and his allies would make sure that the principles for which the war was being fought would then be applied for Ireland’s benefit: “Every act of injustice against Ireland, every insult to her, every attempt to denationalize her, every stupidly insolent act which would rivet the fetters forced on her by a feudal ascendancy party – every such act raises a sigh of sorrow from our breast and awakens within us a burning desire to avenge the injustice.”

When the conflict ended, O’Gorman was awarded the obe for his exemplary service, particularly with the CCS. He returned to Blessed Sacrament in the Glebe and continued the life he had left in 1916: building schools, erecting a new church building, contributing to social-service agencies, researching and writing about Ireland and its culture (he planned to publish a biography of Thomas D’Arcy McGee*), examining Catholic pedagogy, playing golf and tennis, and resuming his fight against eastern Ontario francophones who were intent on restoring instruction in French to the status it had held before the passage of Regulation 17. His rekindled public skirmishes with Franco-Ontarians, particularly over his claim that they imposed unqualified teachers on the board, once again earned him a warning from a superior not to publish controversial articles in the secular press. His pastoral successes, however, were beyond dispute, and Catholics gravitated to his parish. Between 1914 and 1929 his flock nearly doubled, from 251 to 480 families. He was instrumental in bringing to Ottawa in 1926 the Grey Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, who would later invite him to establish Immaculata High School. In 1929 Michael Francis Fallon, bishop of London, recognized O’Gorman’s educational initiatives by appointing him principal of the Summer School of Catechetics in that city. O’Gorman participated in a number of organizations that promoted his many interests. He helped found the Ottawa Boys Club and the Gaelic League of Ottawa. A member of the Canadian Legion since its inception, he also belonged to the Knights of Columbus Council 485 and the St Patrick’s Literary and Scientific Association. Active in the St Vincent de Paul and Holy Name societies, he assisted with the formation of the Catholic University Club, and was for many years vice-president and chaplain of the Ottawa branch of the Catholic Truth Society.

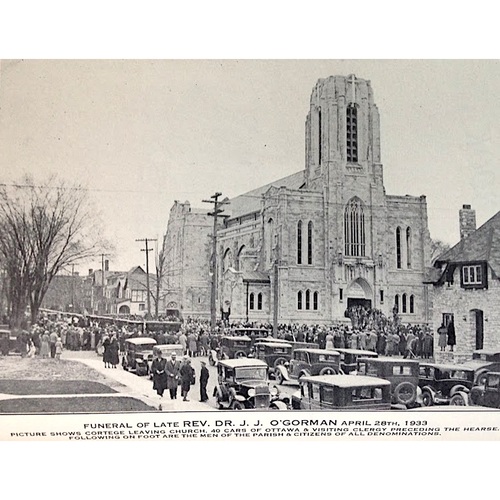

As late as 1932 O’Gorman underwent surgery to remove shrapnel that remained from his war injury. In April 1933 he was rushed to the Ottawa General Hospital for an emergency appendectomy. He developed complications from the operation, possibly aggravated by his old injuries, and died on 24 April 1933 at the age of 49. His death came as a shock. The Ottawa Citizen paid tribute to him as “one of Canada’s most brilliant English speaking Catholic priests.” The obituary in the rival Ottawa Evening Journal might have brought a smile to O’Gorman’s face, capturing, as it did, the priest’s sense of patriotism, Irish ethnicity, and imperial citizenship: “Although deeply interested in the affairs of Ireland, Dr. O’Gorman was a staunch supporter of the British Commonwealth and above all he was one who upheld in every respect the traditions of the Dominion in which he was born.”

The name on the subject’s birth registration (AO, RG 80-2-0-210, no.4435) is John Joseph Patrick Gorman. According to censuses of 1891 (LAC, R233-36-4, Ont., dist. Ottawa (103), subdist. Wellington Ward (E), div. 3: 76–77) and 1901 (LAC, R233-37-6, Ont., dist. Ottawa (100), subdist. Wellington Ward (G), div. 6: 23), the family used the spelling Gorman in those years. The middle name Patrick does not appear on any other known records.

John Joseph O’Gorman’s publications include a biography of Alexander McDonell* called Canada’s greatest chaplain (Toronto, 1916), Canadians to arms! (Toronto, 1916), Divorce in Canada: an appeal to Protestants (Toronto, 1920), Ireland since the Larne gun-running: a chapter of contemporary history, foreword M. F. Fallon (London, Ont., [1920]), The Catholic Church and liberal education (London, Ont. 1923), The Catholic Church (Toronto, 1924), Catholic women and Bible reading (Toronto, [1926]), The Grey Nuns in Pembroke: with a preliminary sketch of the early history of the Grey Nuns (Pembroke, Ont., 1928), Irish Catholic emancipation (Ottawa, [1929]), Three Irish nuns (Kingston, Ont., 1929), Planning the catechism lesson: suggestions based on a revised Munich method (Toronto, 1931), and Souvenir year book of the Blessed Sacrament Church, Ottawa A.D. 1933 (Ottawa, 1933). His writings on McGee include “Thomas D’Arcy McGee – the Irishman – the Canadian – the Catholic” (available at LAC, R1781-0-7, vol.1, folder 2).

Arch. of the Archdiocese of Ottawa, Blessed Sacrament parish papers, annual reports, 1914, 1922, 1926, 1929; J. J. O’Gorman papers; John J. O’Gorman, personnel file. Vatican Apostolic Arch., Arch. Nunz. Canada, 130/1, fasc. 3, J. J. O’Gorman to State Deputies of the Knights of Columbus, 17 April 1917; and fasc. 4, report on Catholic Army Huts by Father Wolston Workman, OFM, 3 April 1918. LAC, R611-360-8 (Canadian Chaplain Service, corr.), vol.4636, file C-O-3 (O’Gorman, J. J.); RG 150, Acc. 1992–93/166, box 7431-50. Catholic Freeman (Toronto), 27 April 1933. Catholic Record (London, Ont.), 6 May 1933. Le Droit (Ottawa), 10 mars 1914, 28 oct. 1915. New Freeman (Saint John), 31 Oct. 1914. Ottawa Citizen, 30 Aug. 1915, 23 March 1917, 10 April 1922, 25 April 1933. Ottawa Evening Journal, 24, 28 April 1933. D. W. Crerar, “Bellicose priests: the wars of the Canadian Catholic chaplains, 1914–1919,” CCHA, Hist. Studies, 58 (1991): 21–39; Padres in no man’s land: Canadian chaplains and the Great War (Montreal and Kingston, 1995). M. G. McGowan, The imperial Irish: Canada’s Irish Catholics fight the Great War, 1914–1918 (Montreal and Kingston, 2017); The waning of the green: Catholics, the Irish, and identity in Toronto, 1887–1922 (Montreal and Kingston, 1999). Helen Nolan and Margaret Foran, Foundation of the Grey Sisters of the Immaculate Conception: Mother St. Paul – foundress ([Pembroke], 2008). J. R. O’Gorman, “Canadian Catholic chaplains in the Great War, 1914–1918,” CCHA, Report (n.p.), 1939/40: 71–83; Soldiers of Christ: Canadian Catholic chaplains, 1914–1918 ([Toronto, 1936]).

Cite This Article

Mark G. McGowan, “O’GORMAN, JOHN JOSEPH (baptized John Joseph Patrick Gorman),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/o_gorman_john_joseph_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/o_gorman_john_joseph_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mark G. McGowan |

| Title of Article: | O’GORMAN, JOHN JOSEPH (baptized John Joseph Patrick Gorman) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2020 |

| Year of revision: | 2020 |

| Access Date: | December 18, 2025 |