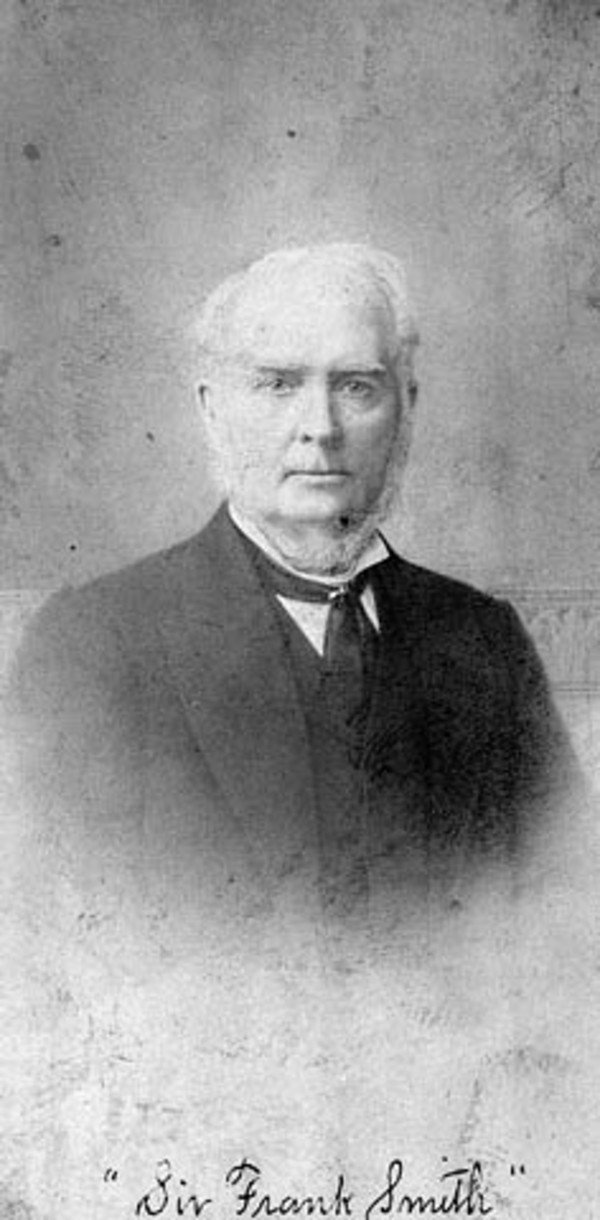

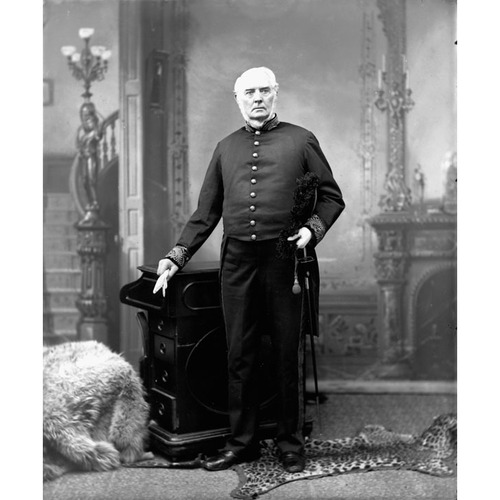

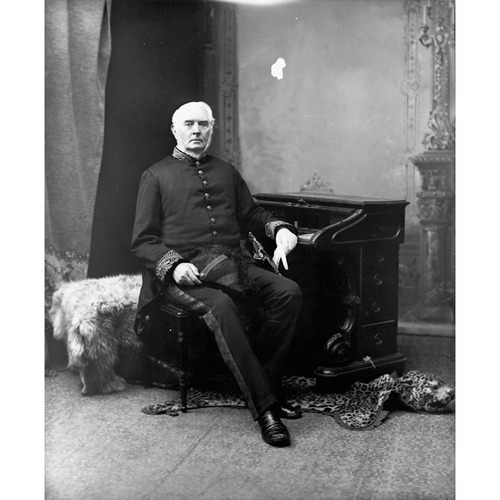

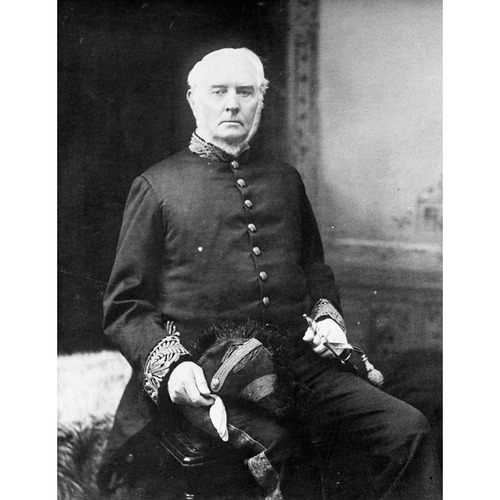

SMITH, Sir FRANK, businessman and politician; b. 13 March 1822 in Richhill, County Armagh (Northern Ireland), son of Patrick Smith; m. Mary Theresa O’Higgins (d. 1896), and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 17 Jan. 1901 in Toronto.

In 1832 Frank Smith’s widowed father, lured by the promise of inexpensive land, immigrated to Upper Canada with his three children. The family worked a small farm outside Port Credit, with the hope of acquiring a larger one in the Talbot settlement, in the southwest part of the province. In 1835 Frank’s elder brother, Joseph, took the family fortune to purchase property there, but en route he was robbed and murdered. Shortly thereafter Smith’s father died, leaving the 12-year-old Frank responsible for the welfare of his sister, Margaret. As a result of this series of tragedies in his early life, Smith developed a gritty determination, industriousness, and a strong will to succeed.

In 1836 Smith, entrusting his sister to the care of a local family and with only $20 to his name, left Port Credit for nearby Sydenham (Dixie), to work for Francis Logan, a grocer. After brief service as a courier in the militia during the rebellion of 1837–38, he returned to Dixie, where he continued his employment with Logan. His “want of education” did not hamper him: he rose from teamster, to clerk, to manager of the retail branches in Toronto and Hamilton, to head of the firm. In 1848 he briefly joined Thomson, Haggart and Company, which operated a general store on the Welland Canal. It was in Hamilton, however, that local entrepreneur Isaac Buchanan* persuaded Smith to forgo his dream of seeking his fortune in the California gold-fields and to persist in the retail business, where he was making a name for himself. With the financial and material help of Buchanan and the Toronto grocery firm of Patrick Foy and James Austin*, he relocated in London and in 1849 established a thriving wholesale and retail grocery business, Frank Smith and Company. Innovative and wise in his investments, he acquired a fortune, largely from liquor sales, and expanded his holdings by establishing retail outlets outside London and investing in the London and Lake Huron Railway.

In 1867 Smith founded a retail store in Toronto with Thomas Wilson and took up permanent residence in the Queen City, though he evidently spent some time in London after 1867 and continued his business there until at least 1872. At his retirement dinner, in 1891, the president of the Dominion Wholesale Grocers’ Guild, William Ince, was to pay tribute to the fact that Smith had once sold $154,000 worth of goods in a day, during one of his famous Toronto “Trade Sales.” Smith invested his profits in railways and banks, and eventually became a director of the Toronto General Trusts Company and Consumers’ Gas Company, vice-president of the Dominion Telegraph Company, and president of the Toronto Street Railway, the Northern Railway, the Dominion Bank (established by James Austin and others), the London and Ontario Investment Company, the Niagara Navigation Company, and the Home Savings and Loan Company. His involvement in Home Savings marked a personal commitment to his Irish Catholic brethren. Its predecessor, the Toronto Savings Bank, had been founded by Bishop Armand-François-Marie de Charbonnel* as a savings and loan company from which Catholics could draw charitable aid without having to go outside the church. Smith, with the help of brewer Eugene O’Keefe*, bailed out the failing bank in 1879 and transformed it into a more secular banking institution. In the process, Smith became a confidant of the bishops of Toronto, and a stalwart in the local Catholic élite. In 1891 he would sell off his various business interests and retire a millionaire.

In the course of building his financial empire and a political career, Smith fashioned himself as an Irish Catholic-Canadian version of an Horatio Alger success story. Some of his business ventures clearly reveal a strain of ruthlessness. His management of the Toronto Street Railway was one case in point. In 1881 Smith became the majority shareholder in that company, assuming the remainder of Alexander Easton’s 30-year contract, signed with the city in 1861. Under Smith the TSR made record profits – $165,562 in 1890 alone – and was targeted by Grip as “Smith’s Goldmine.” Such profitability was made possible, in part, by Smith’s cutting of capital and operating costs, use of aged cars, and requirement that his labour force work 14-hour days, Monday to Saturday, for roughly $8–$9 a week. Smith kept his workers – many of whom were Irish Catholics – in line by forcing them into agreements that prohibited them from unionizing. In March 1886, when they threatened to organize and affiliate with the Knights of Labor, he locked them out, precipitating three days of violence. Despite the support of Mayor William Holmes Howland* and all of Toronto’s major dailies for the workers’ “right of combination,” Smith refused to surrender and permit a union, which he felt would compromise his control. He counterattacked by claiming that the city had failed to keep order, and that, partly because of the mayor’s “shameful” behaviour, the TSR was losing $500 a day. Fearing further lawlessness, Howland back-pedalled and vowed to keep order. After negotiations with the city, Smith agreed to retain the locked-out workers, but only on his terms. He allowed raises in pay, which had been intended before the incident, but refused unionization and eventually fired union organizers.

The unresolved problems between the “tyrannical” Smith and his workers prompted a second strike in May, during which time workers, with Howland’s approval, established the rival “Free Bus Company.” This company ended abruptly in June, when its car-barns were destroyed by fire. Smith won the strike but, in the process, he had exposed himself as an enemy of organized labour, alienated many of Toronto’s Catholic workers, thus limiting his effectiveness as an ethnic leader, and hastened the desire of municipal politicians not to renew the TSR’s contract in 1891. Alexander Whyte Wright*, a labour organizer and Tory stalwart, went so far in June 1886 as to warn Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* that Toronto labourers would blame Smith not as an employer but as a Conservative politician, and workers’ votes would be redirected to the Liberals. Smith left the TSR behind in 1891, with $500,000 in pocket as his share of its sale back to the city.

The TSR incidents underscore how intertwined Smith’s business, ethnic, and political interests had become. His political career had begun as he was building his retailing enterprises in London. From 1855 to 1858 he served as a councillor representing London’s Ward 4; he was acting mayor in 1866 and alderman for Ward 6 in 1867–68. His move to Toronto forced him to resign his seat in March 1868, but it did not end his political career. In the year of confederation he had aligned himself with Catholic politicians attempting to attain just representation for Irish Catholics in Ontario. Smith, who increasingly became identified as a Grit sympathizer, petitioned Macdonald to appoint at least four Irish Catholic senators for Ontario, a request that Macdonald ruled as impracticable, given the favours owed to sitting legislative councillors expecting to be appointed to the new upper house. Undaunted, Smith and other Grit Catholics and Irish nationalists organized a “Catholic Convention” in Toronto in June 1867, which formally petitioned Macdonald for “political rights and privileges” for Irish Catholics. Few clergy approved of the convention since the lay power it represented posed a direct threat to clerical leadership within the Irish Catholic community.

Although Smith appeared to be a firm supporter of the Reform party and such moderate Reform leaders as John Sandfield Macdonald*, Ontario’s first premier, the federal Liberal-Conservative party recognized Smith’s influence among Irish Catholics and attempted to win him over. Through Smith, Sir John A. Macdonald hoped to rebuild his failing relations with English-speaking Catholics and their clergy and prevent the Grits from stealing Irish Catholic votes [see John O’Connor*]. Tory élites in Toronto feared that disenchanted Catholics might redirect their votes to local Reform candidates. Consequently, prominent Tory Catholics, in concert with Bishop John Walsh* of London, anxiously lobbied Macdonald for Smith’s appointment to the Senate. Even Bishop Edward John Horan* of Kingston assured the prime minister in July 1867 that, during a recent meeting with Smith, “his conversation was not that of a Grit.”

Talented in transforming potential enemies into allies, Macdonald skilfully manœuvred to win Smith, and the chunk of the Irish Catholic electorate he might bring with him. While the prime minister manipulated his supporters and government offices to open up a Senate seat, Smith continued his advocacy of Irish rights. In 1869–70 he played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Ontario Catholic League, a Grit-dominated political lobby for more Catholic representation and patronage appointments. With Smith’s political stock strengthened by this show of force, his appointment to the Senate as a Liberal-Conservative in February 1871 was a victory both for the Irish, who gained a broker in Ottawa, and for Macdonald, who retained Irish Catholic support. Not all the Irish were satisfied: Patrick Boyle, editor of the Irish Canadian, saw Smith’s sudden transformation from a Reformer to a Tory as nothing more than an exercise in political self-interest.

Smith’s senatorial career was dominated by two concerns, representation of Irish Catholics and protection of the interests of retailers in Canada. From 1882 to 1891 he served in the Macdonald cabinet as a minister without portfolio, a position that allowed him a great degree of political influence and a generous amount of free time for his business interests. Smith used his stature to procure favours for business colleagues, investigate the fair application of duties and excise on commodities handled by himself and other retailers, protest the passing of the Canada Temperance Act of 1878 as destructive of the livelihood of liquor merchants, and tender his own bids for government railway contracts. An experienced railway executive who recognized the commercial value of railways, Smith became a hardened advocate of government funding for the Canadian Pacific Railway, particularly in 1885, when many Tories opposed extended emergency support. His advocacy was partially the result of self-interest since he was a supplier to the CPR and it owed him money. He also lobbied the Department of Customs for positions for rising businessmen and Irish Catholics. Business advantages aside, Smith found commuting between Toronto and Ottawa so tiring that, in 1879, he had seriously considered seeking the lieutenant governorship of Ontario.

Smith’s role as a broker for Irish Catholic rights also kept him busy. His influence brought immediate results when Macdonald agreed to his request in 1872 that Fenian prisoners be released gradually so as to solidify Irish Catholic support for the government. Furthermore, because of his weight among Liberal-Conservative power-brokers, he was able to secure patronage positions for Irish Catholics, soothe relations between the Catholic hierarchy and the government, lobby Catholic élites during elections, and, in 1884, obtain funds for the Irish Canadian, the Catholic organ run by his former adversary Patrick Boyle. In Toronto he was recognized by both clergy and laity as the Catholic voice in Ottawa, a role that often drew him into crisis situations. In May 1887 a tour by William O’Brien, an advocate of Irish home rule and tenants’ rights, threatened to coincide with a visit to Toronto by Governor General Lord Lansdowne [Petty-Fitzmaurice*], an absentee landlord in Ireland. Irish Catholics would clearly be torn between their sympathy for the plight of Irish tenants and their duty as Canadian citizens to respect the head of state. In communication with Archbishop John Joseph Lynch* of Toronto, Smith attempted to stop O’Brien splitting the community. Although he failed to halt the visit and a minor riot erupted, he used the incident to articulate a new national feeling among the Catholic Irish in Canada. Conditions in Ireland, Smith asserted, were not to interfere with “the happiness of the Catholic people in Canada,” who were “true subjects” enjoying the equality afforded to all Canadians. His convictions underscore the realignment of priorities that would be integral to the identity of new generations of Irish Catholics in Canada.

In late 1887, however, Macdonald appeared to have temporarily lost confidence in Smith’s abilities to command his constituency, perhaps because of the recent Toronto Street Railway imbroglio and the O’Brien affair. Without consulting Smith but reputedly with episcopal support, he appointed two Toronto Liberals to the judiciary, William Glenholme Falconbridge* and Hugh MacMahon. The latter, a Catholic, was clearly selected over Smith’s preferred candidate, James Joseph Foy. Macdonald claimed he had selected the judges on the basis of experience and quality; Smith thought otherwise. Feeling “shut out” as Irish Catholic spokesperson in cabinet, he “attempted to resign.” After negotiating with other prominent Catholic Tories, however, in February 1888 Smith recovered his position in cabinet on his terms – that he would be the authority on Irish Catholic affairs “where the matter is of any importance.” He resumed his cabinet duties, outlived Macdonald, and following the resignation of Sir Hector-Louis Langevin served as minister of public works for a few months in 1891–92 under John Joseph Caldwell Abbott*.

When Sir John Sparrow David Thompson* became prime minister later in 1892, Smith refused a portfolio in cabinet, although he continued to lobby for Irish Catholic representation and patronage. He was well aware that his age and prolonged ill health prohibited him from being as politically active as he had been. In tribute, Thompson arranged for him to receive a knighthood on 25 June 1894. When Thompson died suddenly in December, Governor General Lord Aberdeen [Hamilton-Gordon*] asked Smith to form a new government. Smith declined, but he continued to serve without portfolio in the successive governments of Mackenzie Bowell* and Sir Charles Tupper*. Smith’s reluctance in 1895 to support federal remedial legislation to restore Manitoba’s funding of Catholic schools [see Thomas Greenway] distanced him from French Canadian Catholics in Bowell’s cabinet. Fearing the conflict that might arise from federal coercion, Smith sought compromise and delay. When remedial action became government policy, however, he closed ranks behind Bowell and was one of the few ministers who did not bolt from his cabinet in January 1896 [see John Fisher Wood*]. The defeat of the Conservatives in June abruptly ended Smith’s tenure in cabinet.

Over the next four years, Smith battled rheumatism, gout, and the grippe, which eventually caused his death in January 1901 at home in Toronto among his family. In the opinion of the Canadian Grocer (Toronto), Smith had offered youth an excellent example of how a “strong will . . . able body . . . and business enthusiasm” led to success. During the late Victorian period, Irish Catholics integrated themselves into the socio-economic mainstream of Canadian life, and Smith had helped open up the corridors of power to them. But as their politics became more fluid and new, younger leaders emerged, Smith’s worth as an old-style ethnic politician diminished, bringing a formative era in Irish Catholic politics to a close.

AO, RG 22, ser.305, no.14469. Arch. of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto, L (Lynch papers), AE06.83, .90, 15.11, .13. CTA, RG 5, F, Wards 4–5, 1890. NA, MG 24, B30; MG 26, A; D; E; F. St Michael’s Cemetery (Toronto), Burial records, Smith family plot. Catholic Record (London, Ont.), 18 April 1891. Catholic Register, 14 Feb. 1901. Globe, 11–13 March, 20 May 1886; 28 April 1891; 18 Jan. 1901. Grip (Toronto), 15 Nov. 1890. Irish Canadian (Toronto), 8 Feb. 1871, 9 April 1891. Ottawa Evening Journal, 17 Jan. 1901. Toronto Daily Mail, 12 March 1886; 28 April, 18 May 1891. World (Toronto), 28 April, 18 May 1891.

Armstrong and Nelles, Revenge of the Methodist bicycle company. Can., Senate, Debates, 1895: 665. Canadian album (Cochrane and Hopkins), vol.1. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Commemorative biog. record, county York. Michael Cottrell, “Irish Catholic political leadership in Toronto, 1855–1882: a study in ethnic politics” (phd thesis, Univ. of Sask., Saskatoon, 1988). CPG, 1897. D. [G.] Creighton, John A. Macdonald, the old chieftain (Toronto, 1955; repr. 1965). David Cruise and Alison Griffiths, Lords of the line (Markham, Ont., 1988). Paul Crunican, Priests and politicians: Manitoba schools and the election of 1896 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1974). Directory, London, 1872/73. J. A. Eagle, The Canadian Pacific Railway and the development of western Canada, 1896–1914 (Kingston, Ont., 1989). Guide to Canadian ministries. History of the county of Middlesex . . . (Toronto and London, 1889; repr., intro. D. [J.] Brock, Belleville, Ont., 1972). G. S. Kealey and Palmer, Dreaming of what might be. Desmond Morton, Mayor Howland: the citizens’ candidate (Toronto, 1973). Naylor, Hist. of Canadian business. Political appointments and judicial bench (N.-O. Coté). G. J. Stortz, “An Irish radical in a tory town: William O’Brien in Toronto, 1887,” Éire-Ireland (St Paul, Minn.), 19 (1984), no.4: 35–58.

Cite This Article

Mark McGowan, “SMITH, Sir FRANK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 8, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/smith_frank_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/smith_frank_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mark McGowan |

| Title of Article: | SMITH, Sir FRANK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 8, 2026 |