Source: Link

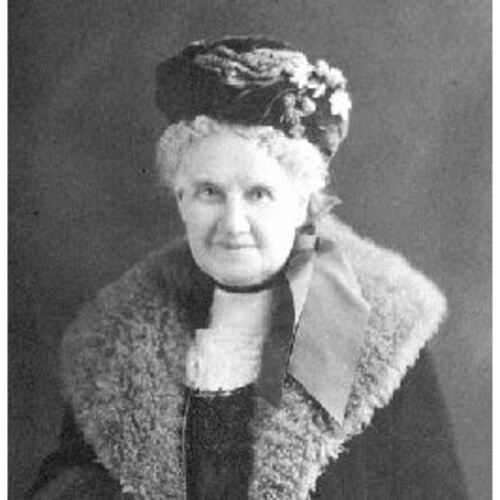

TOWNSEND, MARGARET (Fox; Jenkins), temperance worker, school trustee, and social reformer; b. 4 Aug. 1843 in Neath, Wales, daughter of Joseph Townsend; m. December 1866 Mr Fox (d. 1876) in Coquimbo, Chile, and they had four children; m. 1879 David Jenkins (d. 1904), a widower with nine children, in Chile; they had three children; of her seven children and nine stepchildren, five boys and five girls survived to adulthood; d. 6 June 1923 in Victoria.

The daughter of a deacon in the Congregational Church in Neath, Margaret Townsend began a career in education when she was indentured as a pupil teacher at age 14. She soon became a fully qualified teacher, but a year in a rural school in Great Britain left her with rheumatic fever. Characteristically, she did not allow the illness to slow her for long; Margaret, later described as a woman of “singular activity, both in the mental and physical sense,” went to South America. She had been engaged since 1864 to a Mr Fox, whom she had met in England, and she joined him in Coquimbo, Chile, where they were married shortly after her arrival in December 1866. Margaret opened a school to teach English to the children of Coquimbo.

In 1876 Margaret was left a widow with four young children. Teaching became her main source of income, but after struggling for three years, she “succumbed to an attack of nervous prostration.” Perhaps not coincidentally, her health improved with her marriage in 1879 to David Jenkins. She seemed to be following a pattern: hard work led to illness and then recovery through marriage. Although her later work as a pioneer of the women’s movement belied this pattern of marrying to regain security, she may have come to believe that women needed more options and independence than she had had. Self-interest would not be her sole motivation for pressing for women’s rights. “I consider that women in their public work should lose sight of self,” she later said. She seems to have balanced traditional virtues of womanhood such as self-sacrifice, piety, and devotion to motherhood with political and social ideals that attracted her to social reform, women’s rights movements, and municipal politics.

Margaret, David, their combined family, and an additional three children born to them set sail for Canada on 30 April 1882. The family’s first venture, farming on Salt Spring Island, B.C., failed within a year and they moved to Victoria. She soon applied her formidable energy to various causes.

Between 1883 and 1921 Margaret was a member and office holder of the Welsh Cymmrodorian Society, the ladies’ aid committee of the Metropolitan Methodist Church, the Victoria branch of the Women’s Conservative Club, the Home Nursing Society, the ladies’ auxiliary to the Young Men’s Christian Association, and the Women’s Canadian Club, of which she was president from 1912 to 1921. The two organizations in which she was most involved, however, were the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Local Council of Women. Prompted by a visit from American temperance advocate Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard, Victoria women met to organize a branch of the WCTU in July 1883. Margaret attended the convention, joined the branch, and became corresponding secretary for the provincial union, established at the same time. She hosted many meetings in her home in 1883 and 1884, and in May 1884 she joined the program committee to plan the second provincial temperance convention to be held the following month. At the June meeting, she was appointed organizer for Vancouver Island. The WCTU put forth a plan to circulate books and tracts, to have articles published in the press, and to urge local organizations to forbid the use of alcohol at their gatherings. Its members tied their role in temperance activities to women’s voting rights. In the mid 1880s Margaret and Mrs Anne Cecilia Spofford [McNaughton*] “canvassed the city . . . to get the women of Victoria to vote and thus show their appreciation of the privilege of the [municipal] franchise.” In 1887–88 Margaret was vice-president of the provincial WCTU and in 1900 she became president of the Victoria WCTU.

By 1897 Margaret was a member of the Local Council of Women of Victoria and Vancouver Island [see Edith Perrin*], which she would serve as recording secretary from 1904 to 1910 and as vice-president from 1911 to 1914. She became the council’s candidate for school trustee in the city election of 1897, promoting “compulsory scientific temperance education.” She was Victoria’s third female trustee and served in 1897, in 1898, and from 1902 to 1919. In this capacity she visited schools across the country and in 1912 she introduced a special class for mentally challenged children in Victoria schools. She also helped develop domestic science programs. After leaving the school board in 1919 she remained honorary adviser to the domestic science committee. A new public school built in Victoria in 1914 was named the Margaret Jenkins School in recognition of her work. On her retirement in 1921 local women’s organizations hosted a reception attended by 400 women. They paid tribute to her “extraordinary executive abilities, gracious charm and broad vision.” Her friend and noted fellow suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst said that in her the Canadian Club had had a president “whose abilities had she been a man – which would have been a great loss to womanhood – would have carried her into any position in the Empire or in Canada.” Her granddaughter recalled that even after retiring from public duties Margaret continued to spend many hours visiting hospital-bound war veterans.

Although Margaret Jenkins frequently stated that home and family were her priorities and that a woman’s role as a mother was her most important task, she embraced a life of public service in which her children and husband were rarely mentioned. In her 80th year, two years after she had retired, she suffered a heart attack and died at home. The Daily Colonist reported that “she will be remembered as one of the most . . . influential figures in the New Woman movement.” Her life expressed the contradictions of an era, mixing 19th-century ideals of true womanhood with a public service record that pushed for change and helped launch a “new woman” in the 20th century.

BCA, MS-1961; MS-2227; MS-2818. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 1, 4, 6 July 1883; 11 July 1885; 14 May 1897; 16, 26 Oct. 1921; 7 June 1923; 17 Aug. 1971. Victoria Daily Times, 6, 19 Oct. 1921; 7 June 1923. Elizabeth Forbes, Wild roses at their feet: pioneer women of Vancouver Island ([Victoria], 1971). Lyn Gough, As wise as serpents: five women & an organization that changed British Columbia, 1883–1939 (Victoria, 1988). In her own right: selected essays on women’s history in B.C., ed. Barbara Latham and Cathy Kess (Victoria, 1980). Woman’s Christian Temperance Union of British Columbia, Silver anniversary of the provincial Woman’s Christian Temperance Union of British Columbia, 1883–1908 . . . (Victoria, 1908; copy in BCA, Northwest coll.).

Cite This Article

Melanie Buddle, “TOWNSEND, MARGARET (Fox; Jenkins),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/townsend_margaret_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/townsend_margaret_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Melanie Buddle |

| Title of Article: | TOWNSEND, MARGARET (Fox; Jenkins) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |