Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

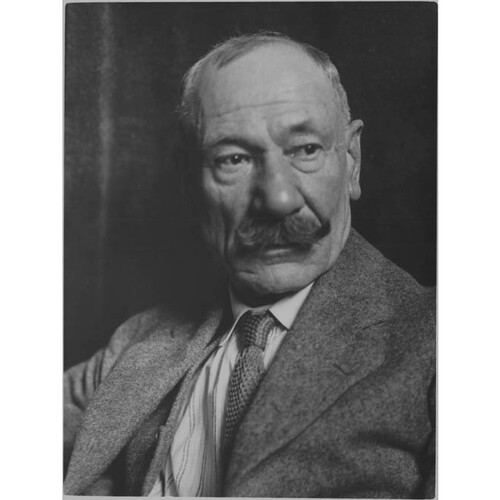

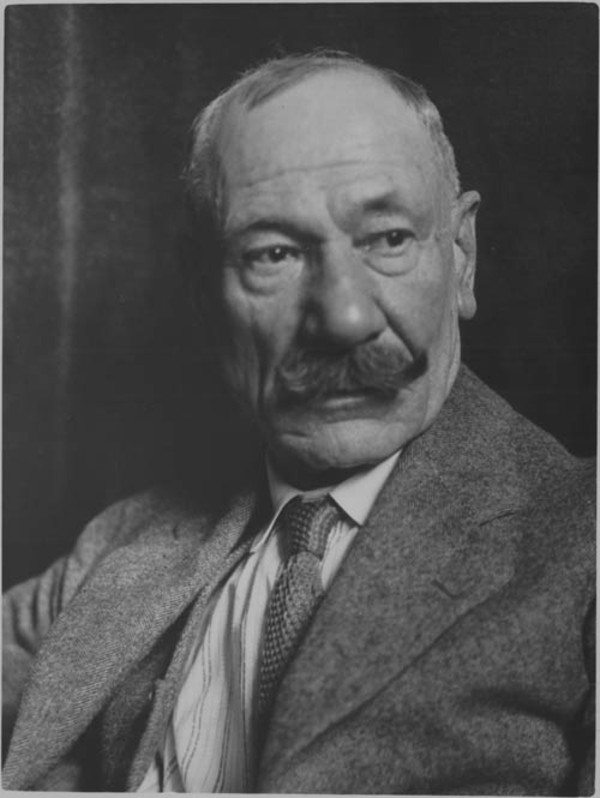

WALKER, HORATIO (he sometimes signed Horatio M. Walker), photographer and painter; b. 12 May 1858 at Listowel, Upper Canada, son of Thomas Walker and Jeanne (Jane) Maurrice; m. 6 Oct. 1877 Jeannette Pretty (d. 15 Dec. 1938) in Toronto, and they had a son and a daughter, both of whom predeceased them; d. 27 Sept. 1938 in the parish of Sainte-Pétronille, Île d’Orléans, Que., and was buried there three days later in the Chapelle Sainte-Mary.

Childhood and training

Horatio Walker’s parents more than likely settled in Listowel in 1856 – at least, that is what Paul Lavoie, his friend and biographer, asserts. Lavoie also states that Horatio’s father, Thomas, was from Yorkshire, England, as confirmed in Thomas’s remarriage certificate. The couple were among the first settlers in the area, where Thomas acquired a piece of land and built a house. In the 1861 census Thomas described himself as a cabinetmaker, and in the next as an artist. He would, however, make a career mainly in the timber trade, working his land and running a sawmill. Apparently, young Horatio developed an aptitude for drawing quite early on and was encouraged by his father, who was said to be an amateur sculptor. Thanks to Thomas, who brought his son along on occasional business trips to the Quebec City region in the early 1870s, Horatio discovered Île d’Orléans, which would become his favourite subject.

After completing elementary and secondary schooling in his native village, Horatio moved to Toronto in 1873. He was hired by the Notman and Fraser photography studio [see William Notman*] as a photo-colourist. There he met Robert Ford Gagen, a colleague some ten years older, who became his teacher and introduced him to the principles of art. He learned to draw and paint from casts and live models. His first canvases were landscapes, genre scenes, and portraits. In a 1931 account Walker stated that his discovery in Toronto of the works of Gainsborough and Constable spurred his ambition to become a professional painter. Unable to see a future for himself in the city, he emigrated to the United States to complete his apprenticeship and launch his career.

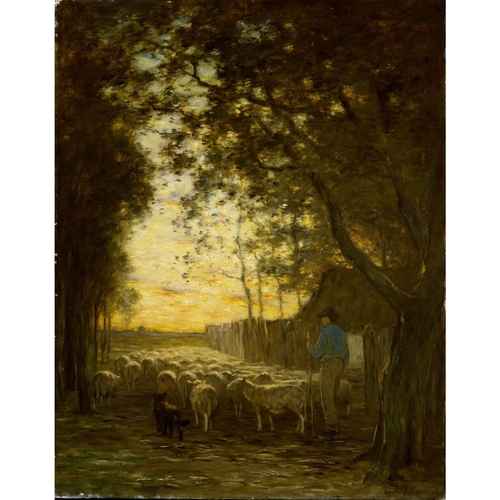

Barely 18, Walker settled in Rochester, N.Y. Equipped with his experience at Notman and Fraser, from 1876 he described himself as a photographer in Rochester’s directory and soon teamed up with the photographer John H. Kent. But he did not forget his initial aspirations: he improved his knowledge of art by studying the great masters. His favourites were the landscape artists J. M. W. Turner, Camille Corot, and Théodore Rousseau as well as the painter of rural life, Jean-François Millet, who would have a marked influence on his work. Walker took advantage of living in New York State to paint nature subjects in the countryside around Syracuse. In his search for pastoral settings he also visited Quebec, accompanied by one Rochester colleague in particular, James Somerville.

Early artistic career

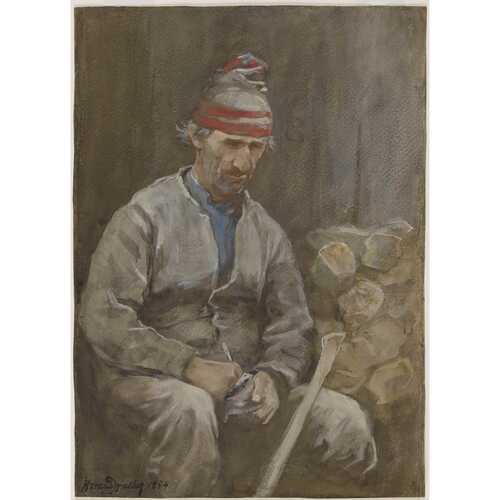

Walker’s career as a painter seems to have blossomed in the late 1870s, when he began to advertise his name along with other portrait and landscape painters in the Rochester business directory. His first known participation in a group exhibition took place in 1880 at the inaugural exposition of the Rochester Art Club, of which he was a founding member. In May of the same year, he travelled to Quebec to undertake a veritable pilgrimage along the length of the St Lawrence valley, starting from L’Épiphanie (not far from Montreal) and reaching Quebec City in November. The journey afforded him an opportunity to paint in the open air and become familiar with the way of life of French Canadian habitants who would provide the inspiration for his work. In 1882 Walker presented the results of his in situ labours – 18 paintings in all – at the annual exhibition of the art club, where he also gave lessons in drawing and watercolour. Several sources report his first trip to Europe during this period; he was said to have spent time in England, Belgium, Spain, France, Ireland, and the Netherlands, visited museums, and met Dutch artists with whom he discovered affinities.

Growing fame in America and awards

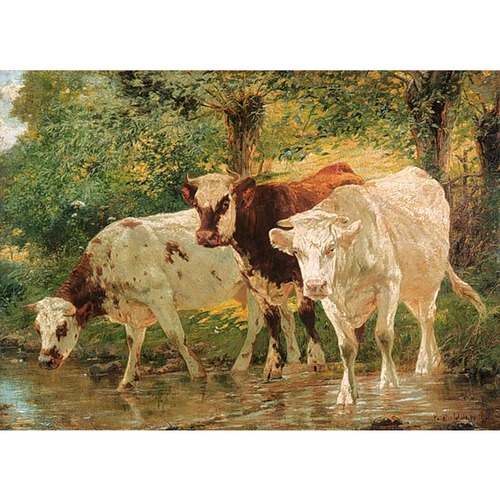

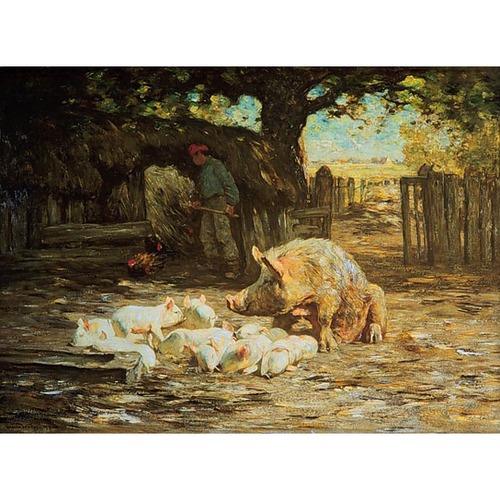

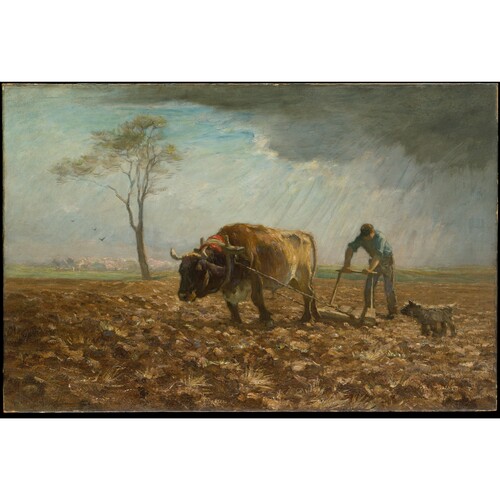

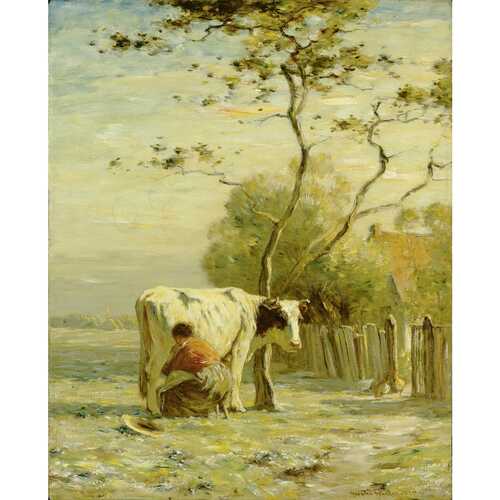

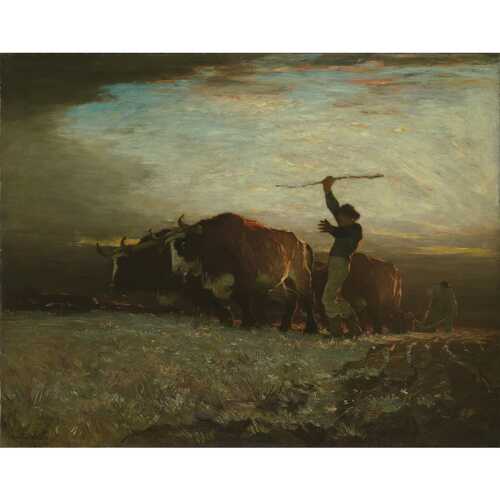

In the United States, Walker increasingly made his mark on the art scene in the 1880s. He participated in several exhibitions in Rochester and New York, notably at the American Society of Painters in Water Colors and at the National Academy of Design. In 1883 he engaged the services of New York gallery owner Newman Emerson Montross, who would remain his commercial representative until 1923: it was he who negotiated Walker’s first sales in the metropolis. His oils and watercolours, executed in a style close to that of Dutch painters and the Barbizon School, mainly featured pigs and cattle as subjects, as illustrated by The batture at Crane Island (1885) and The harrower (c. 1890–95), both very successful. Aware of the urban clientele’s enthusiasm for rural and rustic themes, reminiscent of idyllic bygone days, Walker made increasingly frequent visits to the Quebec City region, which he saw as an Eden. He set up his temporary studio at Russell House and his pied-à-terre at the Hôtel Saint-Louis.

In 1885 Walker left Rochester permanently for New York, where he enjoyed growing fame and achieved true financial security. The following year he became a naturalized American citizen. His years of work bore fruit: he accumulated awards and prizes even in the most prestigious competitions, including those of the universal exposition in Paris (1889) and the Columbian exposition in Chicago (1893), where he received a diploma and a gold medal for his work A stable interior (1887). He was also admitted to major art associations in the United States, including the Society of American Artists (1887) and the National Academy of Design (1890). Despite all his successes, achieved thanks to his portrayals of rural life in Quebec, he remained largely unknown in that province and the rest of the country. The first showing of his work in Montreal took place only in 1900, on the occasion of an exhibition organized by the Art Association of Montreal and devoted to the Maris brothers, Jacobus Hendricus, Matthijs, and Willem. The event allowed the works of the three Dutch painters to be linked to those of the Canadian artist; they all shared an attraction to landscapes and pastoral scenes as well as certain stylistic characteristics, such as using a limited palette.

Dreams of an international career

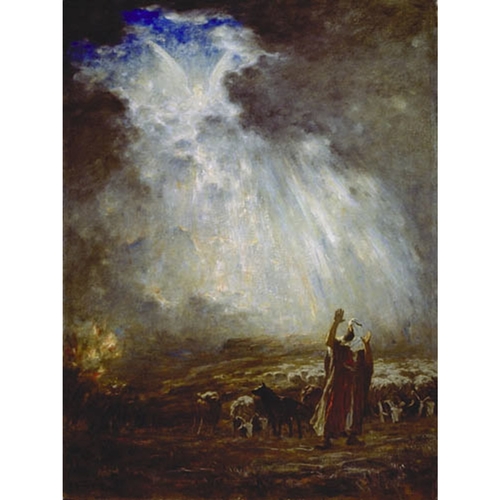

Walker dreamed of an international career. He tried his luck in London, where he settled with his family, probably in 1901. Some works, such as The potato pickers (1890), earned him critical praise and a place in the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours. He pursued work on his favourite themes. The change of environment, however, seemed to encourage him to revisit these subjects, using the new approach he had adopted shortly before his arrival in England. It represented a shift away from the Dutch style. Abandoning watercolours, which had been his preference, he thereafter painted in oils and favoured larger formats. The tight framing around motifs and the chiaroscuro effects he sought from then on lend his rural subjects an “epic” character, a term proposed by the art historian David Karel. The stylistic renewal was favourably received in America but he failed to conquer the European market. After four years in England, Walker abandoned his international ambitions in order to realize another long-cherished dream: to live at the very source of his inspiration, Île d’Orléans, which, as Le Soleil reported on 10 Jan. 1925, he called the “sacred temple of the Muses.”

Île d’Orléans and the Canadian art world

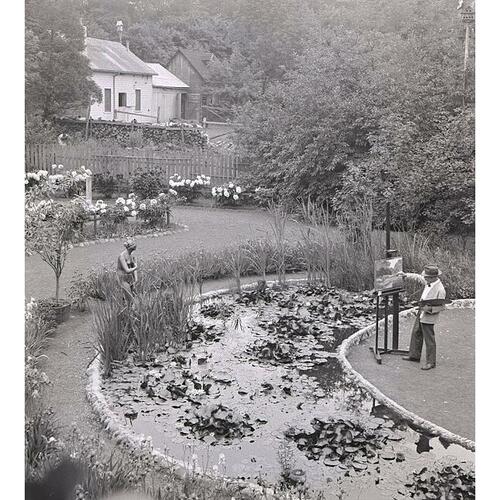

In 1888 Walker had acquired a property in Sainte-Pétronille. He stayed there every summer, probably even during his years in England, and on his return settled there permanently. He retained a residence in New York, however, where he spent the winters. In 1909 he had a studio built adjacent to his Sainte-Pétronille residence, modelling it on those he had seen in England. The pavilion – in which paintings illustrating the allegories of the seasons, dawn, and dusk adorned the main room – would serve him until the end of his life, as much a studio as a reception room for friends and distinguished guests.

Despite his stay in England, Walker’s fortunes had not waned in the United States. On the contrary, his fame had soared thanks to paintings produced in his new style, among which were the famous compositions Oxen drinking (1899) and Ploughing – the first gleam (1900), which earned numerous awards. After winning first prize in 1907 at the Worcester Art Museum’s annual exhibition, Oxen drinking was purchased for a substantial price two years later by the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. As for Ploughing – the first gleam, considered by some his masterpiece, especially because of the chiaroscuro effects that confer an epic character to this scene of daily rural life, it was shown in numerous exhibitions and won several honours before being acquired years later, in 1929, by the provincial government for the future Musée de la Province in Quebec City.

Walker, then at the pinnacle of his career, was henceforth considered a pre-eminent painter, regarded as one of the great masters of American art. He took part in many international exhibitions and sat on juries and selection committees, where he demonstrated his openness to modern art, although his own work looked more to the past.

Once settled on Île d’Orléans, Walker sought, for the first time in his career, to anchor himself in the Canadian art world with the aim of contributing to its development, which, in his opinion, was still in an embryonic state. From 1908 until 1915 he took part in exhibitions of the Canadian Art Club in Toronto and sometimes even travelled to attend its meetings. He befriended some of his fellow artists, including Edmund Montague Morris* and Homer Ransford Watson, who paid more than one visit to Sainte-Pétronille. (Tragically, Morris died following one of these sojourns: he drowned in the Rivière Portneuf at Notre-Dame-de-Portneuf [Portneuf], in August 1913.) In 1915 Walker became president of the Canadian Art Club, but internal conflicts that pitted him against founding member Albert Curtis Williamson*, in particular, drove him to resign in the spring of the following year.

Walker’s influence on the Canadian scene also manifested itself beyond the club’s activities. He was admitted to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1913. An exhibition devoted entirely to his work, organized by his agent at New York’s Montross Gallery, was also held at the Art Museum of Toronto in the spring of 1915. The following year, thanks to the intervention of his friend Professor James Mavor*, Walker was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Toronto. McGill University and the Université Laval bestowed the same honour in 1932 and 1938 respectively.

Last years and assessment

Despite Walker’s success, his career went into decline after the First World War. The themes of his paintings, harking back to the past, no longer seemed to find favour with the American public, which had thus far supported him. When his representative Montross retired in 1923, Walker turned to Frederic Newlin Price and his Ferargil Galleries in New York. Hoping to breathe new life into the painter’s career and open up a market for him, Price, against his client’s advice, mounted an exhibition of his recent work at Montreal’s Watson Art Galleries in November 1925. The venture’s outcome was as Walker had anticipated, leading to the sale of only a single painting, and in 1929 he decided to retire to his island. He signalled the end of his professional activities with a retrospective exhibition, organized without Price’s help, at the School of Fine Arts of Montreal and the Art Gallery of Toronto.

Serious financial problems, which almost bankrupted Walker, shadowed the last years of his life. Medical care for his wife, who had suffered from paranoia since 1914, ate into his savings. His sales, which were already declining in the United States, sank even further during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Yet these setbacks did not completely undermine his morale. He continued to take an active part in artistic life, especially in and around Quebec, where he struck up friendships with several artists, intellectuals, and politicians, among them Clarence Gagnon*, Charles Huot*, Charles-Joseph Simard, and Pierre-Georges Roy*. He made a particular contribution to the illustrations of the latter’s work, L’Île d’Orléans (Quebec City, 1928). He was involved in negotiations intended to influence how art should be taught in the province, and in 1931, following the death of Henry Ivan Neilson on 27 April, he agreed to assume the position of director of the École des Beaux-Arts de Québec on a voluntary, temporary basis. A man of determined, even intransigent, temperament, he subsequently engaged in a fierce struggle with Charles Maillard*, who finally became the school’s director. Walker, who advocated a nationalist approach, accused him of favouring the recruitment of European teachers to the detriment of Canadian candidates. Walker’s later attempts to secure the school’s directorship were fruitless.

Originally from Ontario, Horatio Walker, more than any other Canadian painter of his generation, enjoyed fame and prestige in the United States, achieved thanks to his work celebrating the rural life of his adopted province. Considered the “Millet of the American School” on the New York art scene from 1905 on (according to the periodical Collector and Art Critic), he failed to win commercial success in his native country during his lifetime and had to content himself with accolades. A retrospective exhibition at the Musée du Québec in 1986 would bring him posthumous fame as, in Karel’s words, “[the] herald of Île d’Orléans.”

On the occasion of the Horatio Walker exhibition in 1986, the Musée du Québec published the catalogue Horatio Walker ([Québec]), signed by David Karel. It is the most comprehensive examination of the artist’s life and work. The following year the museum released Les œuvres d’Horatio Walker ([Québec]), compiled by Lyne Gravel, which lists 700 oils, watercolours, drawings, and engravings by the artist.

Some of Walker’s works cannot be located or are in private collections. Others are held by many museums across Canada and the United States. In Canada the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec (the name adopted by the Musée du Québec in 2002) has the most extensive collection. The National Gallery of Can. (Ottawa), the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s Univ. (Kingston, Ont.), the Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ont., and the Art Gallery of Ont. (Toronto), among others, also hold Walker’s works. In the United States they can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, N.Y., and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington).

Ancestry.com, “New York, state and federal naturalization records, 1794–1943”: www.ancestry.ca (consulted 17 Feb. 2020). AO, RG 80-5-0-2, no.357; RG 80-5-0-29, no.13665. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Quebec, non-Catholic parish registers, 1763–1967”: www.familysearch.org (consulted 14 Feb. 2020). LAC, R233-29-7, Canada-West, dist. Perth, subdist. Wallace: 23; R233-34-0, Ont., dist. Perth North (30), subdist. Listowel (h): 2. Le Devoir, 27 sept., 29 oct., 5, 10, 12 nov. 1938. Gazette (Montreal), 22 Nov. 1913. L’Illustration nouvelle (Montréal), 16 déc. 1938. Le Soleil, 10, 12 janv. 1925. Art Assoc. of Montreal, Special loan exhibition of paintings by James Maris, Matthew Maris, William Maris and Horatio Walker, N. A. ([Montreal?, 1900?]). Jean Chauvin, “Horatio Walker,” La Rev. populaire (Montréal), 20 (1927), no.11: 7–9. Directory, Rochester, 1876, 1879. Dorothy Farr, Horatio Walker, 1858–1938 (exhibition catalogue, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 1977). Henri Girard, “Deux peintres de chez nous,” La Rev. moderne (Montréal), 10 (1928–29), no.6: 11, 30. “Horatio Walker,” Collector and Art Critic (New York), 3, March 1905: 35. J. N. Laurvik, “Walker, painter of American peasants,” Arts and Decoration (New York), 1 (1910–11): 63–65, 88. New York Heritage, “Rochester Art Club classes for 1882–3”: nyheritage.org (consulted 14 Feb. 2020). Horatio Walker, Pictures, studies and sketches ([New York], 1915).

Cite This Article

Anne-Élisabeth Vallée, “WALKER, HORATIO (Horatio M. Walker),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walker_horatio_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walker_horatio_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Anne-Élisabeth Vallée |

| Title of Article: | WALKER, HORATIO (Horatio M. Walker) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2022 |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | December 22, 2025 |