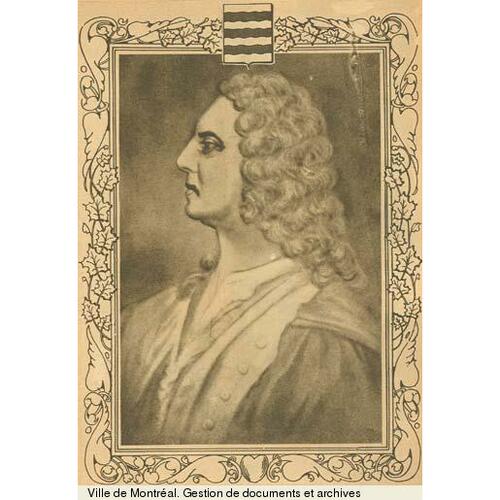

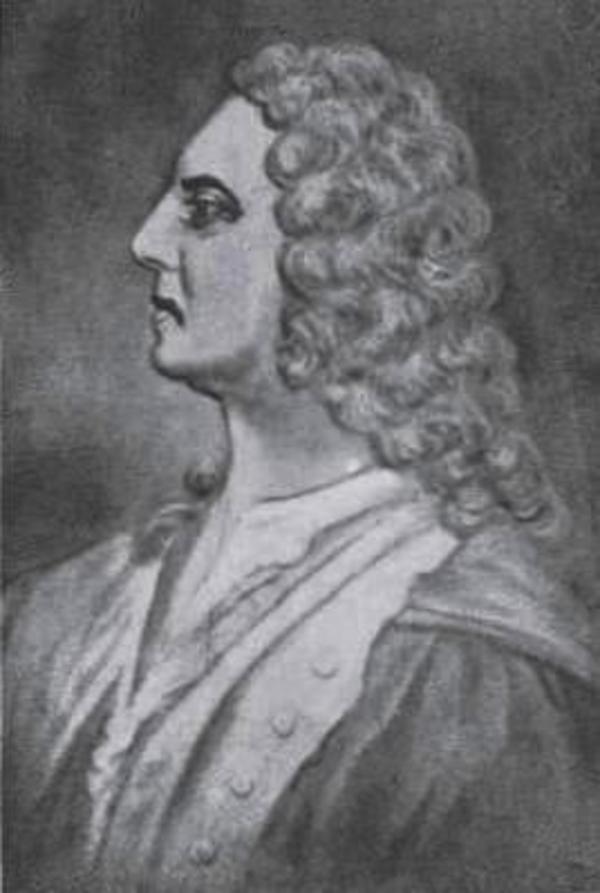

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

SAFFRAY DE MÉZY (or Mésy), AUGUSTIN DE, chevalier, governor of New France 1663–65 (the first to serve directly under Louis XIV, after the king took over the administration of the colony from the Compagnie des Cent-Associés in 1663); died at Quebec in the night of 5–6 May, 1665.

A member of the old Norman nobility, dating back to the mid-14th century, Mézy was reputed to have been very dissolute in his youth. He was major of the town and château at Caen where he came under the influence of M. Jean de Bernières, head of a group of religious devotees at the Hermitage. He then became noted for his great piety. This drew him to the attention of François de Laval*, future bishop of Quebec, who became favourably impressed by Mézy’s character.

In 1663, when Louis XIV and Colbert decided to recall the governor of New France, Baron Davaugour [see Dubois], they delegated to Bishop Laval the task of finding a suitable replacement. The main reason for doing so was not that Bishop Laval wielded such great power but that the king and his ministers were fully occupied with the internal problems of the kingdom. Moreover, it was extremely difficult to find competent officers to serve as governors in the colonies. When Colbert asked the Comte d’Estrades to suggest a man for the Canadian post he refused point blank, declaring, “it is so easy to misjudge men that I must decline to suggest anyone to you for Canada” (BN, Mélanges Colbert, 112 bis, f.573). Bishop Laval was equally reluctant to make the choice but the king insisted and so Laval, remembering the piety and apparent disinterestedness of Mézy, suggested his name. Mézy, however, appeared anything but anxious to accept the appointment, stating that his many heavy debts prevented him from taking up such a post. There being no other candidate available, Louis XIV is reputed to have offered to pay Mézy’s debts if he would accept the appointment for a three-year term and to this Mézy agreed.

On 15 Sept. 1663, Mézy and Laval disembarked at Quebec. With them came 159 indentured labourers and prospective settlers; 60 others had died at sea. Their arrival, and the assurance that much greater aid would be sent from France in the near future, raised the spirits of the 2,500 people in the colony. They could now hope for an early surcease from the constant Iroquois assaults that had bled the colony white. At this time the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy were being hard pressed by their Indian foes, the Hurons, Algonkins, Mahicans and Andastes; in addition they had recently suffered heavy losses from smallpox. When they learned from some of their French captives that reinforcements had arrived in the colony and that more were expected, their attacks on the French settlements slackened and their chiefs began sounding out the Jesuit missionaries on the possibility of a peace settlement. The Jesuit Relation for 1663 reported: “Our enemies, being this year engaged elsewhere, have suffered us to till our fields in safety, and to enjoy a sort of foretaste of the quiet which our incomparable Monarch is about to secure for us. . . . Montreal alone has been stained with the blood of Frenchmen, Iroquois and Hurons.”

The retiring governor, Baron Davaugour, had already left for France when Mézy and Laval arrived and on 18 September the Conseil Souverain was established by virtue of the royal edict of the previous April, which empowered the governor and bishop to select jointly five councillors, an attorney-general, and a recording clerk to serve for a one-year term, renewable if the governor and bishop saw fit. The bishop, or in his absence the senior ecclesiastic in the colony, also had a seat in the council.

In the three days that had elapsed between the arrival of Mézy and the establishment of the Conseil Souverain he certainly had not had sufficient time to assess the merits of those appointed to this body. It is, therefore, more than likely that Bishop Laval selected Louis Rouer de Villeray, Jean Juchereau de La Ferté, Denis-Joseph Ruette d’Auteuil, Charles Legardeur de Tilly and Mathieu Damours De Chauffours as councillors, along with Jean Bourdon as attorney-general and Jean-Baptiste Peuvret Demesnu as recording clerk and secretary. These were men who had played leading roles in the direction of the colony’s affairs under the rule of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés. In fact, in the general administration of the colony and in the method of dispensing justice, the Conseil Souverain took over where the preceding council had left off, serving as a court of appeal and of first instance, and also as the colony’s legislative body. One of the first edicts it issued, on 28 September, forbade anyone to trade liquor, directly or indirectly, with the Indians on pain of heavy fines or banishment. Thus, one of the main causes of conflict between the clergy and previous governors was again removed. To provide funds for the colony’s administration Mézy auctioned off the right to collect the 25 per cent export tax on furs along with a monopoly on the fur trade at Tadoussac; this brought in the sum of 46,500 livres a year for a three-year term.

There was, apparently, a difference of opinion between Mézy and the bishop over his salary and allowances. Some of the clergy later maintained that he had made excessive demands and upon being refused he had “declared war” on the bishop and the Conseil Souverain. There appears to be little truth in these statements. At the meeting of the Conseil Souverain on 28 Nov. 1663 Mézy stated that some “difficulty” had arisen over this matter but he was willing to allow the Conseil Souverain to grant him the same amount as any of the last three governors had received. A week later the council voted to grant him the salary and appointments that had previously been granted to Voyer* d’Argenson. This amounted to 23,303 livres, out of which Mézy had to pay the wages and upkeep of the Quebec garrison.

The following year Mézy had the council remove the 10 per cent tax on all goods entering the colony except on wines, spirits, and tobacco. To protect consumers from overcharging by the merchants, the prices at which all imported goods could be sold was fixed, allowing for a 65 per cent mark-up over the prices paid for similar goods in France. At the same time ocean freight rates were fixed at 80 livres the ton. That these regulations were not to be disregarded was made plain when some merchants were heavily fined for charging more than the tariff allowed.

To encourage the settlers to clear more land and to grow more grain in the face of a large wheat surplus, in 1664 the Conseil Souverain purchased 1,000 bushels, at the generous price of 5 livres the bushel, to be stored for the use of the regular troops expected from France the following year. The wages of indentured labourers were also fixed by law at 60 to 90 livres a year for a three-year term, after which they were free to obtain land of their own. Thus, during the first year of Mézy’s government some worthwhile legislation was enacted. But before that year was out, trouble had arisen between the governor and the bishop.

Mézy, although he represented the king in the colony and had supreme authority, had, in fact, less real power than had the bishop. Mézy had been appointed for only a three-year term and could be recalled by the king at any time. The bishop, on the other hand, was permanently appointed and, in addition to his seat on the council, had the power and prestige of his clerical rank. The clergy had clearly expected Mézy to remain subservient to Bishop Laval, deferring to him in all things, but the governor soon showed he was not prepared to accept a subordinate position.

During the winter of 1663–64 Mézy appears to have become convinced that the bishop, supported by some members of the council, was seeking to undermine his authority. According to the royal edict establishing the Conseil Souverain the governor represented the person of the king; Mézy therefore decided to take steps to assert his prerogatives. On 13 February 1664 he sent the major of his garrison to inform the bishop of his intention to exclude Villeray, d’Auteuil, and Bourdon from the council on the grounds that they had formed a cabal and behaved in a manner contrary to the interests of the king and the people. He also declared that replacements for those now excluded would be chosen by a public assembly. Laval, as was to be expected, refused to entertain this innovation, or to sanction the dismissal of the two council members and the attorney-general. Tilly, La Ferté, and Damours, however, supported Mézy and signed an ordinance suspending Laval’s adherents.

Without an attorney-general justice could not be dispensed and the settlers of the district who had litigation before the court protested vigorously. Mézy therefore asked the bishop to agree to the appointment of a deputy attorney-general. Laval refused to give his sanction but he did declare that he would not openly oppose the governor in any action he took on his own authority. On 10 March the rump council duly appointed Louis-Théandre Chartier de Lotbinière to the vacant attorney-general’s post and the work of the council proceeded. Subsequently, a reconciliation of the disputing factions was effected; Lotbinière gracefully retired and Bourdon was reinstated.

In July, however, trouble again erupted, this time over the election of a syndic for Quebec. The previous November the offices of mayor and alderman had been abolished by the council and it was then decided that the old office of syndic should be reinstituted to represent the interests of the local people before the council. Not until the following August was an election held, when Claude Charron, a merchant of Quebec, was elected in absentia by 23 local residents.

Meanwhile, nearly a year having elapsed since the establishment of the Conseil Souverain, Mézy repeatedly requested Laval to agree to the replacement of some of its members and the confirmation in office of the others. The bishop, obviously knowing which members Mézy wished to exclude, refused to accede to this legitimate request. On 25 August Mézy sent Laval a courteously worded note asking that they should cooperate in good faith to appoint a new council as laid down in the royal edict of April 1663. He proposed that he should draw up a list of 12 men suitable to hold office and that the bishop should select any four; or, the bishop could name 12 candidates and allow the governor to choose four of them. Under the circumstances this was a fair proposal. Laval, however, in a terse note, informed Mézy that he had received word from the minister of marine that Seigneur de Tracy [see Prouville], recently appointed lieutenant-general over all French possessions in America with the powers of a viceroy, would arrive at Quebec the following spring and they should await his arrival before making any changes in the membership of the council. This meant that Mézy would have to face further opposition in the council for the best part of a year. Unfortunately, the terms of the royal edict establishing the Conseil Souverain gave no guidance as to how to cope with an impasse such as this.

After some of the citizens had protested the election of Charron as syndic on the grounds that too few people had voted in the election and that he was more likely to favour the interests of the merchants than those of the consumers, Charron was persuaded to resign and a new election was called. This assembly of voters was also poorly attended and no election was held. Mézy was convinced, rightly or wrongly, that his old foes the clergy and their adherents in the council were responsible for this state of affairs. He therefore sent notes to a large number of townspeople to attend a meeting without stating its purpose. When they had assembled he and Damours held the election and Jean Lemire was duly elected syndic. At the next meeting of the Conseil Souverain, La Ferté, d’Auteuil and the bishop’s deputy, Charles de Lauson de Charny, protested this election and refused to allow Lemire to be installed. By this time Mézy’s patience was exhausted. He regarded this latest move by the bishop’s adherents as chicanery and being, he declared, unaccustomed to such ways, he decided to deal with the situation in the only way he knew how, as would a cavalier defending the king’s interests. On his own authority he dismissed from the council on 19 Sept. 1664 Villeray (who had sailed for France a short time before), d’Auteuil, La Ferté, and Bourdon. As their replacements he appointed Simon Denys de La Trinité, Louis Peronne de Mazé, and Jacques de Cailhault de La Tesserie, with Lotbinière once again to serve as attorney-general and Michel Fillion as clerk. Jean Bourdon, however, unlike the others, refused to accept this dismissal, declaring the governor’s action to be illegal, which it of course was. A violent argument ensued and Mézy lost control of himself. He attacked Bourdon, striking him first with his cane then with the flat of his sword, pursued him out of the chamber and wounded him in the hand. Bishop Laval immediately protested Mézy’s reconstitution of the council, declaring it to be contrary to the king’s edict. The following Sunday he made his views known to the public in a statement read from the pulpit by one of his priests. Mézy, lacking a pulpit, retaliated by posting notices about the town defending his own actions and attacking the bishop, whereupon he was refused absolution by the clergy. The governor’s response was a threat to refuse the authorization of the payment of the semi-annual grant of funds to the clergy.

What the people of the colony thought of this fracas is not known but it certainly could not have enhanced their respect for either the secular or religious authorities. But through it all Mézy’s reconstituted Conseil Souverain continued to function, meting out justice, carrying on the normal processes of the administration, and showing a proper sense of its responsibilities. Then, early in March 1665, Mézy fell seriously ill. When he expressed a desire to be reconciled with the clergy all their earlier rancour was forgotten. Before Mézy expired, during the night of 5–6 May, the bishop said mass for him every day and in his will the governor made bequests to the poor, to charitable institutions, to the church and to five residents of Quebec, one of whom was Villeray.

Shortly before his death Mézy had commissioned Jacques Leneuf de La Poterie to succeed him as his deputy but when the acting attorney general presented the commission to the Conseil Souverain this body refused to register it, maintaining that the governor had no power to appoint his successor – only the king could do this. In France, meanwhile, numerous complaints against Mézy’s conduct had reached the court; Bourdon and Villeray were able to give their version of events at first hand. The minister was thus convinced that Mézy’s conduct could not be condoned. Unaware that the governor was dead, Colbert ordered that the charges against him be investigated and if substantiated he was to be placed under arrest and sent back to France to stand trial.

It is unfortunate that Mézy’s own papers have not survived; were they available to counter-balance the charges levelled at him in the writings of the clergy which have been preserved, he might appear in a better light. At least it can be said that his had been no easy position, sharing power with Bishop Laval. He acted with violence on occasion, it is true; but he did so not without some provocation. Although the clash of personalities played no small part in the conflict, strongly held differences of opinion on what should be done for the better administration of the colony were also involved. In the final analysis the main reason for the eventual impasse was the ill-conceived phrasing of the edict establishing the Conseil Souverain. The governor and the bishop had to share authority and were expected to co-operate in all things. If, for one reason or another, this became impossible, then either the government of the colony was hamstrung or one of them had to over-rule the other and to exercise arbitrary power if the administration were to function. This power the bishop clearly could not wield; but the governor, who was essentially a soldier accustomed to giving orders and being obeyed, readily could and did exercise his authority. In any event, these conflicts should not be allowed to obscure the fact that during Mézy’s brief term as governor, royal government was established in the colony, justice was dispensed equitably and some useful legislation was enacted.

Much of the documentary source material is printed in Jug. et délib., I. The best account to date of Mézy’s administration is that contained in Cahall, The Sovereign Council of New France, 22–36. Faillon, Histoire de la colonie française, III. Gosselin, Vie de Mgr de Laval, I. Lanctot, Histoire du Canada, II. Parkman, The old régime (25th ed.), 145–58.

Cite This Article

W. J. Eccles, “SAFFRAY DE MÉZY (Mésy), AUGUSTIN DE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 11, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/saffray_de_mezy_augustin_de_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/saffray_de_mezy_augustin_de_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | W. J. Eccles |

| Title of Article: | SAFFRAY DE MÉZY (Mésy), AUGUSTIN DE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | March 11, 2026 |