TEKARIHOGEN (Dekarihokenh, Ahyonwaeghs, Ahyouwaeghs, John Brant), Mohawk chief and Indian Department official; b. 27 Sept. 1794 near present-day Brantford, Ont., a member of the turtle clan and youngest son of Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*] and his wife Catharine [Ohtowaˀkéhson*]; d. there 27 Aug. 1832 and was buried the same day.

John Brant probably received some early education in the school for Indian children at the Mohawk village where he was born. Following his parents’ move in 1802 to the vicinity of Burlington Bay (Hamilton Harbour), his education was completed at nearby Ancaster and then at Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake); one of his teachers was Richard Cockrell, a number of whose pupils went on to prominence in Upper Canadian life. Brant must have learned well, for engineer John Mactaggart remarked after making his acquaintance years later, “I have not met a more polite gentleman or a better scholar in all Canada.”

As the War of 1812 approached, many Mohawks, influenced by Red Jacket [Shakóye:wa:thaˀ] and others as well as by unhappy memories of the American revolution, hesitated to commit themselves to a fray. John Brant betrayed no such hesitation and with John Norton and a party of like-minded Indians helped stop an invading American force at Queenston Heights on 13 Oct. 1812. In April 1813 he was made a lieutenant in the Indian Department and he took part in the defeat of the Americans at Beaver Dams on 24 June, a victory that British officer James FitzGibbon* later credited entirely to the Indian contingent. Brant served in most of the subsequent skirmishes on the Niagara frontier and in the battles of Chippawa, Lundy’s Lane, and Fort Erie. On 9 Jan. 1814, disgusted with those of his compatriots who refused to fight, he joined his uncle Henry Tekarihogen, George Martin*, and others in signing a petition that begged the government to withhold the usual annual presents from such disloyal Indians.

Some time after his father’s death in 1807, Brant’s mother had returned to the Grand River, taking the younger children with her. At the war’s end, Brant and his sister Elizabeth went back to the family house at Burlington Bay, where they lived in the English style. Their mother, who preferred Mohawk ways, remained at the Grand River.

Brant must still have been quite young when it became clear that he had the qualities that would fit him for the position of Tekarihogen, the primary chieftainship of the Six Nations Confederacy, which was hereditary in his mother’s family. He could look forward to considerable influence, since to the prestige of that office he would add the knowledge of white ways that had been a major source of his father’s power. As early as 1819 he was assisting Henry Tekarihogen, who was growing old and blind, in the Six Nations’ dispute with white authorities over the nature and extent of their land grant on the Grand River. Governor Frederick Haldimand* had in 1784 bestowed lands “Six Miles deep from each Side of the River beginning at Lake Erie, & extending in that Proportion to the Head of the said River,” and the Indians had been struggling for years to get the grant confirmed by formal deed in fee simple. They were especially anxious about the northern half of their property which had a flaw in its title, this part of the tract not having been bought from its original Mississauga Ojibwa owners before Governor Haldimand made his grant – an error easily explained by the lack of proper surveys and by the general ignorance of the country in 1784. The Six Nations had always expected and hoped that a legal purchase would eventually be made for them which would set this error straight. But when a purchase was finally made in 1819, Lieutenant Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland* informed the Indians in no uncertain terms that the land had been bought for white settlers, not for them.

In 1821 John Brant and Robert Johnson Kerr finally went to England to lobby on behalf of the Six Nations. The two delegates argued that the transfer of the valley from the Mississaugas to the Six Nations had actually been made by an agreement between those groups prior to Haldimand’s proclamation and that the parties to this agreement had understood that the entire valley was being transferred. Brant and Kerr also remarked that it was absurd to maintain that titles were invalid because the king had not purchased the lands from the original proprietors. “The principle is undoubtedly just towards those proprietors,” they observed, “but Europeans have derived their title to the greatest part of America from other sources.” They proposed that their case be submitted to the law officers of the crown. The Colonial Office countered by suggesting that the Indians relinquish their claim to the disputed lands in return for a deed in a fee simple to the undisputed ones. Brant and Kerr offered to accept the deed and leave compensation for the disputed lands to arbitration, but the Colonial Office insisted on its own suggestion and by the end of April 1822 they had given in.

Once the delegates were back in Upper Canada, further difficulties arose. As in the time of Joseph Brant, the provincial government was opposed to any arrangement that would allow Indians to sell their own lands, and it was announced to the Six Nations at a council in February 1823 that if they were to receive their lands in fee simple, they would no longer be entitled to presents. Despite this threat, at a full council on the Grand River in September Brant managed to get the assent of a majority of chiefs to the agreement made in England, and seven chiefs were named as trustees for the lands. The government countered the following spring, when William Claus, the deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs in Upper Canada, told a council that in the opinion of the attorney general the Indians would, as a consequence of the grant in fee simple, become entirely subject to all the laws in force in Upper Canada. A number of chiefs who had supported Brant in September thereupon withdrew their approval and he was left in a minority. Through John Galt* he protested to the Colonial Office in the autumn of 1825, but the vigorous opposition from Upper Canada had won the day and formal control over the sale of Indian lands remained with the colony’s government until 1841. In that year the problem of the alienation of the Grand River lands was finally settled, when the Indians surrendered them to the crown to be managed on their behalf.

Brant was involved in many other activities aimed at improving the lot of his people. In London he had been in contact with the New England Company, a non-sectarian missionary society, and on his return home he worked closely with that organization, welcoming missionaries of all Protestant faiths and encouraging the construction of schools. In 1829 he received a silver cup from the society in recognition of his work.

On 25 June 1828 Brant was officially appointed resident superintendent of the Six Nations of the Grand River, a position which involved close supervision of their affairs and which he held until his death. In practice, he looked after not only the Six Nations but also other Indian groups who had settled alongside them. One of his first challenges was to fight the damming of the river by the Welland Canal Company. The welfare of Indians counted little with the government when weighed against canals, and despite forceful protests made as soon as he read of the scheme, he lost. “I am very anxious to receive His Excellency’s commands as to the Nature of the Explanation to be made to the Six Nations,” he rather pointedly remarked to Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne* in June 1829. In December he wrote, “I have the honor to report . . . that the dam thrown a cross the Grand River by the Welland Canal Company has overflowed the Indian Corn fields their Crops laid waste and their winters provision destroyed.”

Brant also led the Six Nations in their dispute with John Claus, who on the death of his father, William, in 1826 had become trustee for funds belonging to the Indians. The Indians wanted to invalidate an enormous land grant obtained from them by the elder Claus shortly before his death; in retaliation, John Claus withheld the interest on the money of which he was trustee. In this controversy Brant succeeded to the extent that in 1830 Claus was dismissed.

Either with the death of Henry Tekarihogen in 1830 or perhaps shortly before, Brant officially assumed the ancient office and title. Moreover, he ran for the Upper Canadian House of Assembly in the riding of Haldimand in 1830. He took his seat in January 1831 but his election was challenged on the grounds that some of those who voted for him were leaseholders rather than the freeholders required by law, and in February his opponent John Warren was declared elected. Both men died in the cholera epidemic of 1832. In Brant’s case it is not clear whether he succumbed to the disease itself or to the ministrations of the white doctors who were called in to treat him. He was not yet 38.

Many years later, a resident of the Burlington Bay area remembered John Brant at the time he had lived there. He had been a young man fond of dancing who had regularly attended neighbourhood parties and who had “so entirely given up the manner of the Indians that it would not be discovered that he was of the original inhabitants of the Country unless attention was called to it.” Other evidence suggests that, although Brant had adopted an English gentleman’s style of living, he was capable of Mohawk behaviour when dealing with other Mohawks. Yet in personal terms he paid a price for his accomplishments. He never married, and he is said to have commented rather wistfully on the subject to missionary Richard Phelps: “I might have married a fine English lady. I was thought something of there, even by the nobility. I was considered almost a king. But to . . . bring her here and let her see the degraded state of the people that I ruled, would have broken her heart.” He was proud of his heritage, however, and went out of his way to defend his father’s name, taking indignant exception to an article in John Strachan*’s Christian Recorder that portrayed him in an unfavourable manner. He apparently secured an apology from Strachan. When he was in England he undertook to demonstrate to poet Thomas Campbell, who had maligned the elder Brant as “the Monster” chiefly responsible for the “Wyoming massacre” of 1778, that his father was not even present. Campbell later apologized in print to the memory of Joseph Brant.

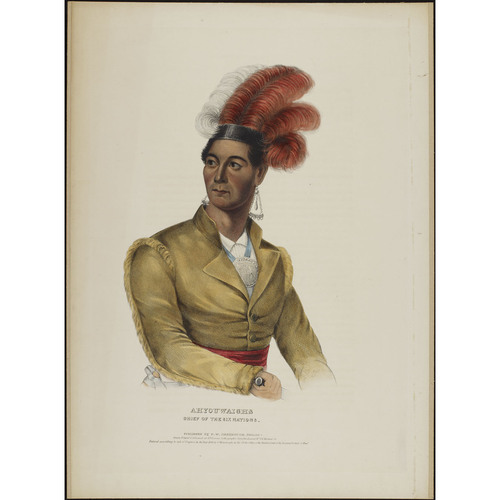

A portrait of John Brant, reproduced in William Leete Stone’s biography of Joseph, reveals an amiable countenance but little of his Indian heritage. He was broad shouldered and about six feet three inches tall – an impressive height for the time. What struck people, however, was his bearing. Jurist Marshall Spring Bidwell* remembered his “dignity and composure,” and Phelps was awed by “the dignity, the authority, the power there was in [his] look, gesture and emphasis.”

AO,

Cite This Article

Isabel T. Kelsay, “TEKARIHOGEN (Dekarihokenh, Ahyonwaeghs, Ahyouwaeghs) (John Brant) (1794-1832),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tekarihogen_1794_1832_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tekarihogen_1794_1832_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Isabel T. Kelsay |

| Title of Article: | TEKARIHOGEN (Dekarihokenh, Ahyonwaeghs, Ahyouwaeghs) (John Brant) (1794-1832) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1987 |

| Access Date: | November 6, 2025 |

![Ahyouwaighs, Chief of the Six Nations [John Brant] Original title: Ahyouwaighs, Chief of the Six Nations [John Brant]](/bioimages/w600.1879.jpg)