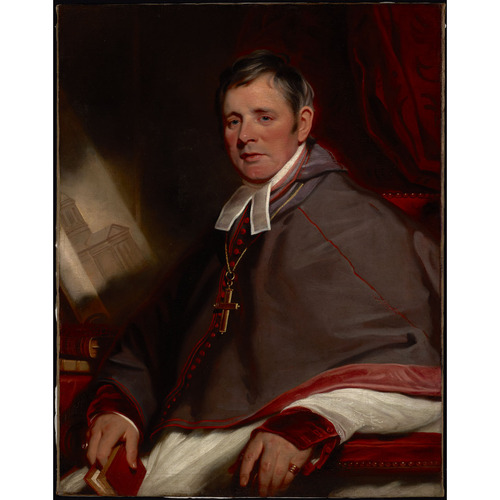

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

McDONELL, ALEXANDER (from 1838 he signed Macdonell), Roman Catholic priest and bishop, office holder, and politician; b. 17 July 1762 in Glengarry, Scotland; d. 14 Jan. 1840 in Dumfries, Scotland.

Alexander McDonell, to whom Thomas D’Arcy McGee* would refer as the “greatest Tory in Canada,” belonged to a Highland clan which had supported Prince Charles, the Young Pretender, in 1745, and had suffered the consequences of his failure. Despite harsh government measures to repress Highland culture after the rebellion, the Macdonells and many other Jacobites were quick to enter British military service when the occasion offered. Perhaps their attitude showed simply an acceptance of the inevitable or, more likely, it reflected the conviction of the Catholic clergy that only loyal submission would bring relief. Because of the penal laws the young Alexander McDonell, as other Catholics, received only a sketchy education at home and had to go abroad for formal religious training. After entering the Scots College in Paris, he went on to the Royal Scots College at Valladolid, Spain, in 1778 to complete his studies for the priesthood. Moulded by the theology and morality taught there at the time, McDonell emerged strictly orthodox and deeply conservative. On 16 Feb. 1787 he was ordained and he returned to the Highlands as a missionary priest that year. A huge man who would always have a problem with his weight, Big Sandy or Mr Alistair as he was known served first in Badenoch and then in Lochaber, ministering to his flock of Gaelic-speaking crofters.

But the clan system, with its reciprocal rights and obligations, was collapsing. McDonell sought employment for his parishioners in Glasgow and succeeded in placing them in the expanding cotton industry. Early in 1792 it was decided that he should be given charge of the Glasgow mission. Economic respite for the Highlanders was short-lived, since the outbreak of war with revolutionary France in 1793 disrupted trade with Europe and they were once again in desperate straits.

Some time that year, Father McDonell made contact with the young and Protestant clan chieftain, Alexander Ranaldson Macdonell of Glengarry, to whom he swiftly attached himself. Either singly or together, they concocted a scheme of offering the unemployed Highlanders to the British government as a fencible regiment, willing to serve outside England or Scotland, unlike the other fencibles who claimed to be home defence units. After a trip to London to seek acceptance of the plan, McDonell returned briefly to Glasgow and the displeasure of his bishop, who was distressed by the priest’s neglect of his mission. Although appearing contrite, McDonell was determined to follow Glengarry, perhaps aspiring to bring him back to the Catholic fold, more likely hoping to find some alternative employment for his people.

In any event, the offer of service was accepted by the British government. The Glengarry Fencibles were embodied with Glengarry as colonel; Alexander McDonell was appointed chaplain on 14 Aug. 1794, the first Catholic chaplain in the British army since the Reformation. The regiment went to Guernsey in 1795, to remain in relative idleness guarding against a French invasion which never came. When rebellion broke out in Ireland in 1798, the fencibles were hastily transferred there. During the four years that his regiment served in Ireland, McDonell lost few opportunities to reinforce the reputation of the Catholic Highlanders for devoted loyalty. He was determined to make himself as useful as possible to the British authorities, never questioning the extent to which influence and patronage affected the success of people or policies.

The brief Peace of Amiens in 1802 brought the disbanding of many non-regular regiments and McDonell’s people were once again without support. Even worse, McDonell himself was betrayed by Glengarry, being unfairly left responsible for the chieftain’s debts, and had to endure the humiliation of a stay in prison. Prospects in Scotland were still gloomy after his release in January 1803, and he resolved to persuade the government to acknowledge the regiment’s service by making grants of land in Upper Canada to its former members. His conservative sympathies would have made the United States an unacceptable refuge and he resisted proposals that he lead his flock to the Caribbean. The positive inducement which drew him to Upper Canada was that many Glengarry Macdonells who had fought as loyalists in the American revolution had relocated in the eastern end of this remote province, where a county had been named Glengarry. Moreover the military service of McDonell’s group had earned them influential friends such as Lieutenant Governor Peter Hunter*, who had been their commander in Ireland and who had said he would welcome them to Upper Canada.

McDonell left Scotland in early September 1804. He was on his way to a province where Catholics were few and where he would be the only priest. On his way through Lower Canada he called on the coadjutor bishop, Joseph-Octave Plessis*, and on 1 Nov. 1804 received ecclesiastical jurisdiction from the bishop, Pierre Denaut*. Plessis, who succeeded Denaut early in 1806, was the only member of the French Canadian hierarchy with whom McDonell ever developed a warm relationship. The two became firm friends and Plessis saw in McDonell a useful ally in his plan to divide the enormous diocese of Quebec, which included all of British North America. As a first step, he appointed McDonell his vicar general and informed him privately that he would be named bishop of Upper Canada, in partibus, as soon as the division took place.

Meanwhile McDonell had established himself at St Raphaels, in Glengarry County, but his field of action was all of the province. He worked to secure the promised land grants for the former fencibles, saw to it that friends and relatives received appointment as surveyors and sheriffs, and acquired sites in Kingston and York (Toronto) for future churches. His own salary was paid in Montreal by the governor-in-chief, an arrangement McDonell believed implied official recognition, besides making him somewhat independent of the local government at York. He immediately began a long campaign to have the government of Upper Canada provide salaries for Catholic priests and teachers. In his view there were many advantages to such an arrangement, both for the church and for the authorities. Dependence on government, he argued, would ensure steady loyalty, and the state in return would be committed to the continuing support of the church. In addition, the Catholic clergy, freed of reliance upon their congregations for maintenance, could exercise a greater influence over them. Although the early response to this scheme was encouraging, a number of years would pass before it was achieved, and part of the cost would be a rupture with John Strachan*, the leading figure of the Church of England in the province.

In the mean time, the deterioration of relations between Britain and the United States presented McDonell with a challenge rife with opportunity and eventually brought him to provincial prominence. In 1807 he had urged that the Glengarry men be enrolled in the militia and Colonel Isaac Brock*, for one, familiar with the priest’s past military exertions, was enthusiastic. Governor Sir James Henry Craig* decided, however, that McDonell’s enthusiasm was greater than his ability to raise a regiment, and the proposal was shelved. Just prior to war’s outbreak, Brock was administrator of Upper Canada and commander of the forces there. He welcomed a hurried visit by McDonell to York and quickly approved the raising of a Glengarry regiment, happy to have men of proven loyalty amid a population he viewed with considerable suspicion. Governor Sir George Prevost* agreed and, without waiting for the assent of the home authorities, on 24 March 1812 ordered formation of the regiment. Father McDonell, of course, was chaplain.

But there were other ways in which the priest would serve. He took an active and effective role in the provincial election of 1812, made more exciting by the dangers of war. Glengarry was no problem. It was not only solidly tory, but solidly Macdonell. According to writer John Graham Harkness, the clan “seems to have had a monopoly of Parliamentary honours . . . of the members elected to the Assembly . . . from 1792 to 1840, all [but two] were connected by blood or marriage with the Macdonells.” With Glengarry well in hand, Father McDonell, at the urging of the future chief justice, Archibald McLean*, intervened in Stormont and Russell in support of John Beikie, the government candidate, who succeeded in turning out the incumbent, Abraham Marsh, a sharp critic of the administration. McDonell’s timely message to the Catholic community contributed to the desired result.

Altogether, McDonell’s fortunes prospered during the war. Brock’s most acute strategic problem was his line of communications to Lower Canada and its vulnerability to American attack along the waterways. With the approval of Prevost, in 1813 McDonell was appointed commissioner to oversee the cutting of a road to link the two provinces. Such recognition greatly enhanced his prestige, not least on account of the substantial patronage he thus acquired for the Eastern District. The Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles acquitted themselves admirably in the war and writer William Foster Coffin* would later liken McDonell to “a medieval churchman, half bishop, half baron, [who] fought and prayed, with equal zeal, by the side of men he had come to regard as his hereditary followers.” His salary was doubled and he won the warm support of the new administrator of Upper Canada, Gordon Drummond*, in his renewed attempt to get Catholic priests on the government payroll. The loyal support of the war effort by Upper Canadian Catholics, McDonell argued to Prevost, made clear the beneficial effect that would flow from firm and steady leadership.

McDonell was soon to have the opportunity to make his case at a higher level. In June 1816 Plessis joined him in Kingston to consecrate the first Catholic church there and begin McDonell’s long association with what would become his episcopal see. Plessis had decided that the aftermath of the war provided the opportune time to forward his plan for dividing the diocese of Quebec, and McDonell was to be his chosen instrument. This role would require a journey to London and allow McDonell to seek the approval and the intervention of the British authorities in support of government salaries for Catholic priests and teachers in Upper Canada. He set off from Halifax in the autumn of 1816 on his twofold mission.

Upon his arrival in London, McDonell began a virtual year-long siege of the Colonial Office. Lord Bathurst, the colonial secretary, seemed willing enough to satisfy Plessis’s wishes but, as McDonell well knew, the matter would have to be handled very delicately. He proposed to Bathurst that the diocese be divided into vicariates apostolic rather than independent sees, which would have carried territorial designations and alarmed the Church of England. Taking a curiously gallican line, he argued that since the vicars apostolic would owe their positions and thus their loyalty to the British government, imperial interests would be as well served as the administrative convenience of the Catholic Church in British North America. The colonial secretary was apparently convinced. London informed the Vatican that it would favour such a division of Quebec and recommended those whom it considered suitable as vicars apostolic – names which McDonell had provided and which included his own.

McDonell also sought to persuade Bathurst that government support for Catholic teachers and priests would further the interests of the state. Immigration to Upper Canada quickened after the war and he proposed a seminary to train a Catholic élite which would guard the faithful against the infection of democratic influences from the United States. Such an élite would also assume positions of responsibility in the local government. It was not at all lost on McDonell that John Strachan, recently appointed executive councillor, was introducing his former pupils into important offices; he did not wish the Catholics to be left behind. After much hesitation on Bathurst’s part and importuning on McDonell’s, the colonial secretary partially met the request. On 12 May 1817 he approved the salaries but directed that they be paid out of Upper Canadian revenues. McDonell would have greatly preferred to have them paid from London and thus be independent of the provincial government, but he had to be content with this limited success.

If not a triumph for McDonell, the journey had clearly been useful, and he returned to Upper Canada late in the autumn of 1817. Some time would pass before his negotiations concerning the division of the diocese bore fruit. It was only in January 1819 that the Vatican made him and Angus Bernard MacEachern* vicars apostolic and titular bishops subordinate to Plessis, who was named archbishop. Plessis had not been consulted and for various reasons was not pleased with the arrangement. As a result the briefs were never executed. New ones were issued in February 1820 and McDonell was made titular bishop of Rhesæna, suffragan, and episcopal vicar general. On 31 Dec. 1820 he was consecrated at Quebec in the chapel of the Ursuline convent.

Meanwhile the rumour that McDonell was to be made bishop and government salaries paid to Catholic priests and teachers had been received with indignation by John Strachan. Jealous of the position of the Church of England and anxious about his own prospects for a mitre, Strachan, as McDonell correctly surmised, used his influence to block the appropriation of the salaries from government revenues. It would be several years before Bathurst’s promise would be redeemed. McDonell had also had to contend with that recurring upset of colonial political life, the appointment of a new lieutenant governor. Francis Gore* was succeeded in 1818 by Sir Peregrine Maitland*, who for ten years was the focus of power relationships in Upper Canada and exercised a determining influence in the complex patronage network which sustained the governing élite. The political arm of this élite was led by Strachan and John Beverley Robinson*, who acquired much control over the lieutenant governor. It was during Maitland’s term of office that this “family compact” reached its zenith. They were never to have the same position with his successors.

McDonell’s demonstrated loyalty, conservative ideology, and power over the people of his district made him of considerable utility to the government. Although he could never be of the family compact, given their determined support of the Church of England as the established church, he was certainly with them in their stout resistance to republican and levelling influences. He equally shared their attachment to Britain, but like Strachan, he was never an uncritical colonial. To the extent that McDonell buttressed the local government and its conservative policies, he was accorded a share in the patronage system, consulted by officials in matters of concern to him, and assured full consideration of his opinions on public affairs. In a real sense, he was an associate member of the governing élite and by the end of the 1820s was perceived by radical critics of the government as a pillar of its support.

In bringing himself to Maitland’s attention, McDonell relied on the useful web of Scottish sympathies in the Canadas. He secured a charter from the Highland Society of London and, in concert with many of the partners and senior officials of the North West Company, formed the Highland Society of Canada. He successfully induced Maitland to accept election as its first president and modestly assumed the office of vice-president himself. His intimacy with the Nor’Westers was due not only to romantic sentiment for the Highlands. They contributed to his building campaigns and covered his bank loans. McDonell, in return, persuaded Plessis to delay the introduction of more missionaries to Red River because a successful colony there would threaten the NWC’s activities. Only after the company’s merger with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821 was McDonell at all encouraging in his advice to Plessis about western expansion of the church.

Maitland saw in McDonell a useful ally and, in recognition of his acceptability, he was named to the land board of the Eastern District, made a member of a committee investigating the purchase of Indian lands, and appointed one of the commissioners to end the long dispute over the boundary of Upper and Lower Canada. Thus encouraged, McDonell prevailed on Maitland to intervene in the matter of the promised salaries. He now strengthened his argument by pointing to the growing influx of Irish Catholics, whose “turbulent disposition and want of control” would require careful handling by additional priests and teachers, preferably from Ireland. Maitland acceded to the request; but although McDonell was gratified that the 1823 appropriations included the long-delayed salaries, he was determined to visit England to collect the arrears he felt were owed by the colonial secretary.

There were other issues as well that McDonell’s presence in London might forward. Plessis still hoped that the division of the diocese of Quebec would be complete; that is, that McDonell and his fellow vicars general MacEachern, Jean-Jacques Lartigue, and Joseph-Norbert Provencher* would be made bishops-in-ordinary with their own diocesan sees and suffragan to himself as metropolitan. The colonial secretary had been reluctant to accept the implications of four more independent Roman Catholic bishops in British North America. With the powerful support of Governor Lord Dalhousie [Ramsay], Plessis and McDonell judged the time appropriate for a personal and private approach to Bathurst.

In addition, McDonell had been taking a hand in the intensifying political debate in 1821–22 over the proposal for a union of Upper and Lower Canada. Claiming that the Eastern District of the upper province was stoutly opposed to such a union, he joined Strachan and Robinson in arguing that all of Upper Canada would be irreparably injured. Louis-Joseph Papineau* tried to recruit McDonell as part of a Lower Canadian delegation bound for London to protest. McDonell declined on the ground that he would not be able to proceed to Britain until the spring of 1823. He did write flattering letters of introduction for Papineau, although he soon changed his opinion. But his concern about the impact of any union upon French Canadians was patent. They must not be provoked into disaffection, he wrote in January 1823 to his old friend Lord Sidmouth. “Both the Canadas are filling fast with Scotch Radicals, Irish rebels and American Republicans.” A combination of these elements could well end the connection with Britain. Though written partly for effect, the letter reveals that his concerns were broader than the interests of Upper Canada alone.

McDonell left Upper Canada in the spring; his journey was to keep him away for over two years but would see the accomplishment of most of his objectives. After fortuitously meeting John Beverley Robinson in London and being reassured that the bruited union was a dead issue, he made a brief visit to the Highlands. He took the occasion to cultivate John Galt, a founder of the Canada Company. In return for much useful information on land matters in Upper Canada, including the most recent report of the Crown Lands Department, McDonell received some stock in the new company and, later on, a beautiful church site in its chief town of Guelph. Upon his return to London, his personal business with the Colonial Office drew his immediate attention. Somewhat to his surprise, Lord Bathurst capitulated readily in the matter of the arrears, and the Treasury, through the timely intervention of the bishop’s cousin Charles Grant, the future Baron Glenelg and colonial secretary, agreed to a payment of £3,400 in full settlement. McDonell’s high standing with the Colonial Office was further witnessed when Bathurst increased his salary to £400, a reward endorsed by Maitland, Dalhousie, and even John Strachan.

The erection of separate dioceses in British North America took considerably more time. Bathurst had given up his former opposition, partly at Dalhousie’s urging. Despite Bathurst’s willingness, however, McDonell finally had to travel to Rome in the spring of 1825 to assure the Vatican that the creation of new Roman Catholic jurisdictions in a non-Catholic land would not cause an unfavourable reaction and, indeed, had the approval of the British government. Formal presentations to the assembled cardinals and the tedious wait for the lumbering Vatican bureaucracy to produce results were eventually followed by papal sanction of three new dioceses, Kingston (1826), Charlottetown (1829), and Nova Scotia (1842).

It was August of 1825 when McDonell returned to London to share his achievement with the colonial secretary. But it became evident that Bathurst was now much preoccupied with the effect of increasing immigration to British North America by the Irish and, in particular, the dangerous prospect that they might coordinate activities with Daniel O’Connell in the United Kingdom. The bishop seized the occasion to seek more funding for Irish priests who could exercise a firm control over their restless flocks. It was a foretaste of the years of anxiety McDonell would be caused by events in the Irish Catholic community of Upper Canada. Soon after his arrival home in the autumn of 1825, he accompanied Maitland on a tour through the recently settled Irish districts in the Ottawa valley and enlisted his support. Although the lieutenant governor was sympathetic, he promised no funds and McDonell eventually received £750 annually from Bathurst. The colonial secretary diverted the funds from the proceeds of the Canada Company to provide salaries for additional Irish priests.

Early in 1826 Upper Canada became the diocese of Kingston and McDonell its bishop (he often used the form Regiopolis). The announcement of his appointment drew the somewhat petulant envy of Strachan, but did not prevent McDonell’s active collaboration with the governing élite in the provincial election of 1828. He even attempted, though unsuccessfully, to induce Attorney General Robinson to stand for election in Glengarry. The riding was safe enough, although to McDonell’s dismay the Catholics were unable to agree on a candidate and a Presbyterian supporter of the government was returned. More appalling, however, was the fact that the new House of Assembly contained a majority of critics and opponents of the executive, marked, if not led, by the increasing radicalism of William Lyon Mackenzie*.

Equally disconcerting that eventful year was the prospect of a new lieutenant governor. Maitland’s replacement, Sir John Colborne*, was an unknown quantity. The bishop would soon be seeking his aid to help him channel the Irish Catholic immigrants into respectable paths. And among those recent immigrants was a priest named William John O’Grady, whose erratic career would challenge the bishop’s influence over his flock and drag him more deeply into the politics of Upper Canada.

McDonell welcomed O’Grady at first, convinced as he was that Irish priests were best suited to Irish Catholic congregations. In January 1829 he gave O’Grady the important, and visible, charge at the provincial capital, since the Catholics in York were overwhelmingly Irish. O’Grady was also entrusted by the bishop to act as intermediary with Lieutenant Governor Colborne. McDonell was pleased enough with his performance to give O’Grady the power of vicar general early in 1830. But disturbing rumours began to circulate in York that O’Grady was neglecting his pastoral obligations, that he was too familiar with a local woman, and, worst of all, that he was meddling in reform politics and was increasingly identified with Mackenzie. In the summer of 1832 McDonell determined to end such scandal by transferring O’Grady to Brockville. When O’Grady refused, the bishop felt that he had no alternative but to suspend him from the priesthood.

O’Grady appealed to Colborne in January 1833 to intervene on his behalf, and the whole affair became distressingly public as Mackenzie’s Colonial Advocate supported O’Grady and the bishop’s authority was warmly endorsed by the Canadian Freeman, edited by Francis Collins*, and Thomas Dalton’s Patriot and Farmer’s Monitor. The public was treated to almost weekly instalments of the controversy in the press. It was a painful and difficult episode for McDonell, not least because he had had such hopes for O’Grady. In the bishop’s view, the reputation of the Catholic population for loyalty and respectability was at stake and hence the future of the church in Upper Canada. It was not so much that O’Grady was meddling in politics that exercised McDonell, but that he was doing so in the wrong cause. The bishop would never concede that supporting the government was anything but one’s proper dutet he could hardly denounce O’Grady for his political activity without being accused of hypocrisy. The rebellious priest had therefore to be censured on ecclesiastical grounds of insubordination to his religious superior.

Colborne was not impressed by O’Grady’s tortured argument that jurisdiction over the church had passed from France to Britain with the conquest, thus giving the lieutenant governor, as the representative of the crown, the right to intervene in the quarrel. After consulting his law officers, Colborne simply passed the matter on to the colonial secretary, who supported the bishop’s authority as well. After an unsuccessful visit to Rome, O’Grady abandoned his challenge and in January 1834 returned to Upper Canada where, as a journalistic ally of Mackenzie, he continued to bedevil the bishop. While McDonell considered himself vindicated, he was deeply scarred by the dispute. He would never again give his trust so fully to another newcomer, and his ecclesiastical authority was exercised far more closely over his clergy thenceforward. Nor would he retreat from open political activity since the reputation of the Catholics of Upper Canada for loyalty had to be redeemed.

His own public position was secure. He was a sincere admirer of Colborne and, for his part, Colborne welcomed McDonell’s support. One of his first objectives in Upper Canada had been to broaden representation in the Legislative Council and the bishop was one of the first appointees recommended to the Colonial Office. The mandamus summoning him to the council was dated 13 Sept. 1830, but because of illness he was not sworn in until 21 Nov. 1831. Although he attended only infrequently, McDonell saw his appointment both as a personal honour and as recognition of the just place of Catholics in the public life of the province. All churches, he hoped, would now be placed on an equal footing, and by churches he meant the churches of England, Scotland, and Rome, since all others were merely sects. Colborne, and also the new governor, Sir James Kempt*, were quite open to him in matters of patronage, providing land for new churches and salaries for additional priests to attend the steady stream of Irish Catholic immigrants

McDonell continued to engage in partisan political activities, and was therefore among the targets of Mackenzie’s frequent diatribes against the provincial executive. After successive expulsions from the assembly, Mackenzie carried his cause to the Colonial Office in the summer of 1832. His wide-ranging strictures included a direct attack on the presence of Strachan and McDonell in the Legislative Council. The response of Colonial Secretary Lord Goderich, a long letter of 8 Nov. 1832 to Colborne which became widely known as the Goderich memorandum, caused a sensation. Although Goderich discounted Mackenzie’s more inflammatory accusations, the colonial secretary apparently concluded that much was awry in the distant colony. He informed Colborne, inter alia, that he had little sympathy with the continuing presence of McDonell and Strachan in the Legislative Council. In February 1833 the tories passed a stinging rebuke in the council, denouncing Mackenzie, rejecting Goderich’s ill-informed intervention, and warmly defending the two clergymen. The independence of the upper house must be maintained, they countered, if its essential role as balance-wheel of the constitution was to be protected. The connection with Britain would only be threatened by such wrong-headed meddling by Colonial Office officials acting on such wicked and malicious testimony as that of Mackenzie. Goderich was shortly replaced by Lord Stanley and the issue subsided, but it made clear that Upper Canadian tories were anything but submissive colonials. In a letter to Sir James Kempt, McDonell drove home the point. The allegiance of Upper Canadians was fragile and could be disrupted as well by the reluctance of the home government to sustain the local executive as by the machinations of the unprincipled Mackenzie, he wrote.

Throughout 1833, the bishop remained at York to re-establish harmony in the distracted congregation and to exploit his friendship with Colborne. But he was now 71 and eager to set up permanent residence in Kingston. He wished also to be free of the routine administration of the diocese. He had begun the laborious process of persuading Quebec, London, and the Vatican to approve the appointment of an acceptable coadjutor. Such was his standing with the authorities, both political and ecclesiastic, that in the end matters went surprisingly swiftly. He avoided potential quarrels between the Scots and Irish in his flock by selecting a priest from Lower Canada, Rémi Gaulin*, who spoke English. It was a happy choice and McDonell could confidently turn over the running of the diocese to his new coadjutor. There would, however, be little leisure and no withdrawal from the public eye. The election of 1834 threw the province once again into political turmoil.

Perhaps it was complacency, but the tories put little effort into the campaign and failed utterly to recognize the rising tide of unrest that swept the reformers into a majority in the assembly. Bishop McDonell took no part in the election in Kingston where Christopher Alexander Hagerman easily turned back the challenge of O’Grady. Elsewhere in the province, including the Eastern District, tory candidates were overwhelmed. In Glengarry, Alexander McMartin*, the tory stalwart, was defeated by the bishop’s radical cousin, Alexander Chisholm. It was hardly McDonell’s fault. Nevertheless, it was clear that even the Highlanders were susceptible to reform agitation and could not be taken for granted. The election produced a fractious assembly with a disunited reform majority, mostly moderates, but with a determined band of radicals led by Mackenzie. McDonell and the tories would pay a high price for their neglect.

The bishop and his colleague in the Legislative Council, Archdeacon John Strachan, were favourite targets of the radicals in the assembly and the experience drew the two churchmen closer together. McDonell even supported Strachan’s continuing crusade for a mitre. He wrote to his cousin Lord Glenelg, who was now colonial secretary, advocating the promotion. Strachan was touched by McDonell’s support and, although unsuccessful at the time, he soon became bishop of Toronto. The two would have need of each other in the future as Mackenzie continued his attacks. Having persuaded the assembly in 1835 to create a special committee to investigate the grievances of the province, with himself as chairman, Mackenzie devoted a surprising amount of time to harassing Strachan and McDonell. Much of his evidence came from private letters of McDonell to O’Grady when the latter was still acting as vicar general. Few of the moderate reformers took the former priest seriously, but McDonell was greatly embarrassed by the affair.

Misreading the special committee’s report as the considered opinion of the assembly, the Colonial Office concluded that matters in Upper Canada were at a sorry pass and decided to replace Colborne as lieutenant governor. McDonell rose to his defence and in a bitter letter to his cousin the colonial secretary in December 1835, denounced Mackenzie and his wicked fulminations. Mackenzie, meanwhile, had launched an inquiry into the funds that the bishop received from the Canada Company and demanded an accounting. McDonell flatly refused and was supported by Glenelg.

Shortly after his arrival in January 1836, the new lieutenant governor, Sir Francis Bond Head*, received a petition from the assembly which demanded, among other things, that McDonell and Strachan be compelled to resign from the Legislative Council. When asked by Head for his comments on the petition, McDonell stoutly refused to give up his post. He had no intention of showing “so much imbecility in my latter days, as to relinquish a mark of honour conferred upon me by my Sovereign to gratify the vindictive malice of a few unprincipled radicals.” He defended Strachan as well, claiming that “I never saw him engaged in any political discussion of any kind”! “Politics” were only indulged in by opponents of the government. Both Head and Glenelg were apparently satisfied by the response.

In any case, the dispute was soon lost sight of as relations between the assembly and Head collapsed completely. In the summer of 1836 the province was plunged into its most violent election campaign ever. McDonell gave his complete attention to the Eastern District. The issue was clear – defence of the constitution against disloyalty. The bishop issued an address “to the Catholic and Protestant Freeholders of the Counties of Stormont and Glengarry.” Accusing the radicals of attempting to sever the connection with Britain and preventing necessary expenditures on roads, canals, and other improvements, he went on to defend Sir Francis as a true reformer. Even the Orange order hailed his performance, cancelling its traditional parade at the capital on 12 July and toasting the bishop’s patriotism. Supporters of the government took 10 of the 11 seats in the district. McDonell and the tories seemed well satisfied with the result, but the electoral defeat would soon drive Mackenzie to more desperate measures.

The bishop used his considerable credit with Head and the executive to secure a bill of incorporation for a seminary early in 1837. He was well aware, however, that the struggling Catholics of Upper Canada were in no position to finance it. He faced the prospect of another journey to Britain to seek funds for an adequate endowment. But he was soon caught up in local events. The Catholic hierarchy still sought the creation of a separate ecclesiastical province in British North America, which would involve the tricky problem of getting the British government to recognize the Catholic bishop of Quebec as metropolitan without provoking anxiety in the Church of England. The Lower Canadian bishops again turned to McDonell for help and he made an extended visit to Montreal and Quebec in the summer of 1837. He persuaded the governor, Lord Gosford [Acheson], to support the initiative in London, but the matter added yet another reason for McDonell to travel to Britain.

He returned to Kingston in the early autumn of 1837 to make preparations for the journey and found the upper province in a state of great excitement. With many of the moderate reform leaders, such as Robert Baldwin* and Marshall Spring Bidwell*, withdrawn from active politics, Mackenzie was lashing out randomly at all his many antagonists. Perhaps equally important, the tories had lost confidence in Head, whose ideas on economic development, especially banking, ran counter to their own. Despite McDonell’s implacable opposition to Mackenzie, the bishop was not blind to the political resentment against oligarchic control. In a letter to Lord Durham [Lambton] after the rebellion, he condemned the radicals but could not refrain from pointing out that many Upper Canadians were angered at seeing “a certain party in and about Toronto assume too much power and exercise what they think too much influence . . . so much so that there is hardly a situation of trust or emolument but what is engaged by themselves and their friends.” When the vexed question of the clergy reserves and the pretensions of the Church of England are added, McDonell was not far from the position of the moderate reformers. But on the question of rebellion, there could be no intermediate position.

During the border excitements of 1838, McDonell fretted about the unreliability of much of the population of the province, saw military ineptitude everywhere, and drew on his past exploits to urge the formation of fencible regiments to defend Upper Canada. As the emergency receded, the bishop turned to the familiar problem of accommodating himself to a new lieutenant governor. He headed an impressive list of local notables who welcomed Sir George Arthur* to Kingston. The two would get on famously. He also made an urgent plea to Lord Durham to resolve the question of the clergy reserves, which the bishop argued was the single most distracting issue in the province. Durham included McDonell’s letter in his Report as evidence for his blistering attack on the reserves. When the rebellion erupted again in Lower Canada after Durham’s departure, McDonell even volunteered, “old and stiff as I am,” to take the field at the head of his clansmen. Arthur declined his offer politely but followed his recommendations for appointments. The bishop’s most effective action was a well-circulated address to the inhabitants of Glengarry in which he rallied support for the government. With Arthur’s encouragement, he also published a similar address to the Irish Catholics of the province.

In the new year, 1839, the threat of invasion receded, and the politically active turned to the debate over Durham’s recommendation for a “responsible” executive. McDonell took no part in the discussions. He was finally preparing for his much delayed return to England and Scotland to raise funds for his seminary, Regiopolis College, the cornerstone for which he hopefully laid in June. Sir George Arthur was as encouraging as possible, even proposing to name the bishop an official emigration agent of the province and defray his expenses. McDonell sailed from Montreal on 20 June 1839.

After 40-odd years, the bishop was well known to Colonial Office officials. But in truth, there was little he could accomplish in seeking to persuade them that he and his church were entitled to a share in the clergy reserves. At that moment, the energetic Charles Edward Poulett Thomson, who would be appointed governor in September, was preparing a scheme for their distribution. So while McDonell received a friendly and sympathetic welcome, his task was impossible. He would have to rely on whatever private funds he could raise for his seminary. He attempted, as well, to meet his obligations to Sir George Arthur. In early October he travelled to Scotland and then Ireland, hoping to induce the local bishops to support his emigration schemes. Pneumonia laid him low in Dublin and, after an apparent recovery, he returned to Scotland. But at Dumfries, on 14 Jan. 1840, he weakened and died.

McDonell’s death coincided almost exactly with the end of the separate existence of Upper Canada. So also would pass from the philosophy of toryism there the values he saw as essential to true liberty – order, stability, deference. His profound social and political conservatism would become as irrelevant as the oligarchy with whom he had quarrelled, cooperated, and struggled to make Upper Canada a British haven for Scots and Irish Catholics.

This work has been drawn almost exclusively from primary sources.

AO, MS 4; MS 35 (mfm. at PAC); MS 78; MS 498; MU 1147; MU 1966–73; MU 3389–90 (photocopies at PAC). Arch. of the Archdiocese of Kingston (Kingston, Ont.), A (Alexander MacDonell papers). Arch. of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto, M (Macdonell papers). Archivio della Propaganda Fide (Rome). PAC, MG 19, A35; MG 24, A27; A40; J1; J13, Alexander McDonell, “The Glengarry Highlanders” (transcript); RG 1, E3; RG 5, A1; C2; RG 7, G1; RG 8, I (C ser.). PRO, CO 42. Scottish Catholic Arch. (Edinburgh), Blairs letters; Preshome letters. SRO, GD45 (mfm. at PAC). Arthur papers (Sanderson). U.C., House of Assembly, Journals; Legislative Council, Journals. Canadian Freeman. Chronicle & Gazette. Colonial Advocate. Kingston Chronicle. Kingston Gazette. Patriot (Toronto). Caron, “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Plessis,” ANQ Rapport, 1927–28, 1928–29, 1932–33. Desrosiers, “Inv. de la corr. de Mgr Lartigue,” ANQ Rapport, 1941–42, 1942–43, 1943–44, 1944–45, 1945–46. Craig, Upper Canada. J. G. Harkness, Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry: a history, 1784–1943 (Oshawa, Ont., 1946). Lemieux, L’établissement de la première prov. eccl. H. J. Somers, The life and times of the Hon. and Rt. Rev. Alexander Macdonell . . . (Washington, 1931). Maurice Taylor, The Scots College in Spain (Valladolid, Spain, 1971). K. M. Toomey, Alexander Macdonell, the Scottish years: 1762–1804 (Toronto, 1985).

Cite This Article

J. E. Rea, “McDONELL (Macdonell), ALEXANDER (1762-1840),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcdonell_alexander_7E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcdonell_alexander_7E.html |

| Author of Article: | J. E. Rea |

| Title of Article: | McDONELL (Macdonell), ALEXANDER (1762-1840) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1988 |

| Access Date: | July 24, 2025 |