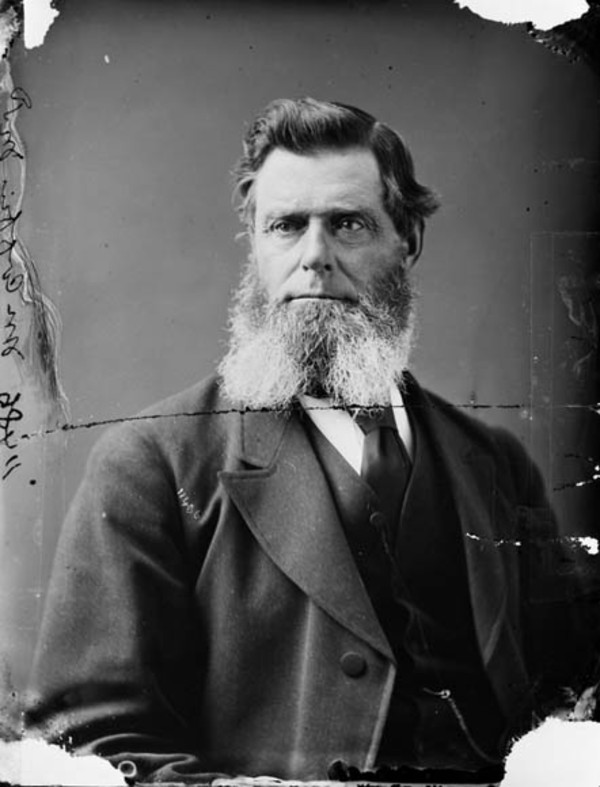

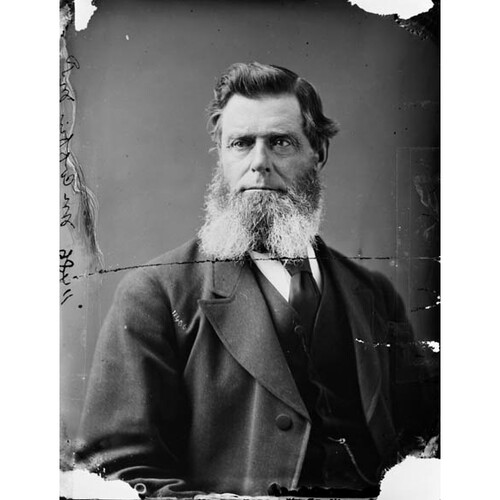

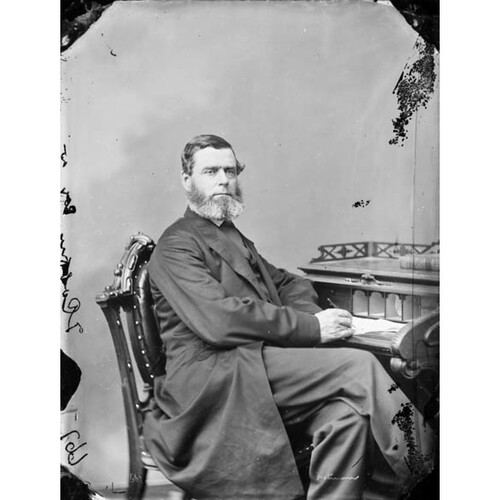

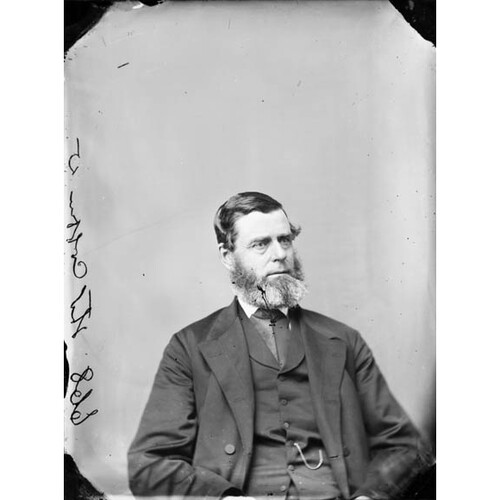

COFFIN, THOMAS, merchant, shipbuilder, and politician; b. 1817 in Barrington, Shelburne County, N.S., son of Thomas Coffin and Margaret Homer; m. first in 1840, Sarah Doane; m. secondly in 1870, Adeline Coffin; several children were born of each marriage; d. 13 July 1890 in Barrington.

Thomas Coffin’s family had been engaged in farming, shipbuilding, fishing, and general trade since its arrival in Shelburne County from Nantucket (Mass.) in the 1760s. His father trained his sons to carry on in these occupations, and when an adult Thomas conducted lengthy trading voyages as captain. He prospered sufficiently to build a large store in 1856 on one of the two wharves his father owned at Shelburne. Like many other merchants in the 1850s Coffin was attracted to shipbuilding, and in 1853 he and his brother James joined with James Sutherland and his sons to acquire timber lands and sawmills on the upper reaches of the Clyde River. From 1854 until the late 1870s they operated a shipyard on the river, producing several barques, brigantines, and schooners, including two ships over 1,000 tons each.

As a member of a well-established family and a prosperous businessman in his own right, Coffin considered it his duty to perform public service. Though his own formal education was apparently limited, he was appointed commissioner of schools for the western district of Shelburne County in 1849, and again from 1854 to 1857; he was also school commissioner for the Barrington district in 1857–58 and 1864. He had been named a justice of the peace in 1855, and despite his lack of any legal training he served on the court of probate from 1861 to 1865.

Coffin’s most prominent public role began in 1851 when he was elected as a Reformer to represent Shelburne County in the House of Assembly. He rarely spoke in the house, did not take an active part on committees, and introduced only a few bills pertaining to shipping or trade. In 1851, in one of his rare speeches, he defended Joseph Howe*’s proposal for constructing a railway from Halifax to Windsor because it would “give to those engaged in the prosecution of the fisheries an increased market.” Coffin’s support was surprising to Howe since the other western county members, particularly Thomas Killam* of Yarmouth, denounced the project as a threat to the fisheries. Coffin usually voted, however, with other merchants to reduce tariffs and oppose the extension of aid to railway construction and manufacturing industries. In the general election of 1855 Coffin lost his seat, but he regained it in 1859. Although frequently absent from the assembly, probably because he was at sea, Coffin supported Howe’s sorely pressed administration when he was present. In the general election of 1863 Coffin was one of only 14 Liberals returned to a house of 55 members. He was soon caught up in the debate over union of the British North American colonies and joined with members from the western counties in opposing the scheme. Coffin apparently saw in union threats of increased tariffs and emphasis on the development of the upper provinces.

Coffin’s opposition to confederation was undiminished by the passage of the British North America Act, and in the federal election in September 1867 he was elected by acclamation to represent Shelburne in the House of Commons. He attempted to remain neutral when in 1868 bitter strife broke out between Howe and the anti-confederate provincial administration of William Annand. Sir John A. Macdonald*, refusing to recognize Annand’s government as the legitimate voice of the province, had chosen instead to deal with Howe and the other federal members of parliament. Howe, who had come to accept union as inevitable, was negotiating with Macdonald to improve the financial terms of Nova Scotia’s entry into confederation. The split between the federal and provincial anti-confederates elected in 1867 was put to political advantage by Coffin: in Ottawa he became identified as a supporter of Macdonald’s government, a position useful for patronage purposes, while at the county level he retained ties with the supporters of the anti-confederate provincial ministry. This tactic helped him win the 1872 general election, again by acclamation.

Coffin and other Nova Scotia members of parliament became dissatisfied, however, with Macdonald’s policy of arbitrarily choosing members of his cabinet, who in turn were expected to direct the votes of the members of their respective provincial caucuses. The Nova Scotians wanted themselves to select and dismiss their cabinet representatives and to be involved in decision making. Howe’s resignation in May 1873 opened up a cabinet post coveted by several members, including Coffin. Disappointed in his pursuit of office, Coffin pledged his support to the leader of the opposition, Alexander Mackenzie*. When the Pacific Scandal forced the resignation of Macdonald’s cabinet in November 1873 and a Liberal government was formed, the ten Nova Scotia supporters of Mackenzie decided that the two members of parliament with the longest records of parliamentary service, Coffin and William Ross, should become ministers. Unable to resist the dictates of the Nova Scotia group, Mackenzie reluctantly appointed Coffin receiver general.

Returned by acclamation in the ensuing by-election and in the general election of February 1874, Coffin soon revealed his deficiencies as a parliamentarian and minister. His position was made secure, however, when Mackenzie dismissed William Ross because he doubted his judgement and honesty. The Nova Scotia caucus denounced Mackenzie’s action as arbitrary; the appointment to the cabinet in September 1874 of William Berrian Vail*, who represented a Halifax faction, was equally resented. In such circumstances, Mackenzie felt he could not afford to remove Coffin, whom he thought had “neither talent, tongue or sense,” but he briefly considered abolishing the office of receiver general as a means of ridding himself of his unsatisfactory colleague. Coffin’s downfall finally came in the federal election of 1878 when he was soundly defeated by Thomas Robertson*, a prominent provincial Liberal. Coffin never again ran for political office and, embittered by what he considered treachery on the part of both provincial and federal Liberals, supported the Conservatives until his death in 1890.

Coffin’s attempts to fulfil his self-conceived ideas of social responsibility required political abilities he did not possess. His insistence on remaining in the cabinet prevented Mackenzie from searching for a Nova Scotian who could have contributed to cabinet decisions and acted as a spokesman for government policies in the province at a time when the Liberals sorely lacked both political leadership and public appeal. It was fortunate for Coffin’s self-esteem that he did not realize that by clinging to office he had betrayed the interests of his own party and helped to cause the Liberal defeat in 1878.

PANS, ms file, Coffin family. Shelburne County Court of Probate (Shelburne, N.S.), Book 3, Will of Thomas Coffin. Acadian Recorder, 8 Sept. 1870. Morning Chronicle (Halifax), 1864–74. Morning Herald (Halifax), 1878, 15 July 1890. Novascotian, 1851–67. Yarmouth Herald (Yarmouth, N.S.), 15 July 1890. CPC, 1876. Edwin Crowell, A history of Barrington Township and vicinity, Shelburne County, Nova Scotia, 1604–1870; with a biographical and genealogical appendix (Yarmouth, [1923]; repr. Belleville, Ont., 1974). K. G. Pryke, Nova Scotia and confederation, 1864–74 (Toronto, 1979). Thomson, Alexander Mackenzie. K. G. Pryke, “The making of a province: Nova Scotia and confederation,” CHA Hist. papers, 1968: 35–48.

Cite This Article

Kenneth G. Pryke, “COFFIN, THOMAS (1817-90),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 6, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/coffin_thomas_1817_90_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/coffin_thomas_1817_90_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Kenneth G. Pryke |

| Title of Article: | COFFIN, THOMAS (1817-90) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | November 6, 2025 |