Source: Link

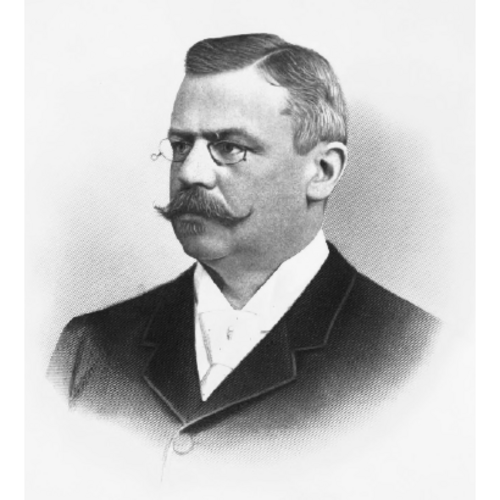

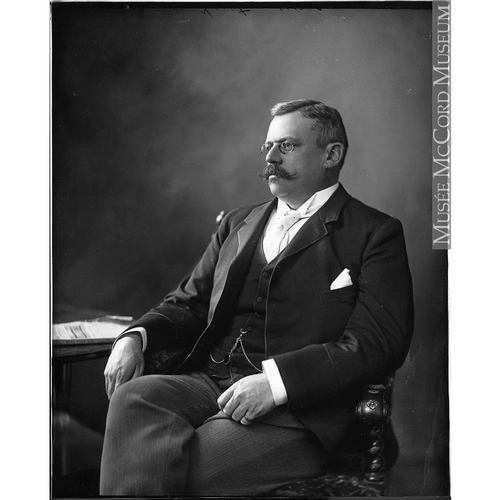

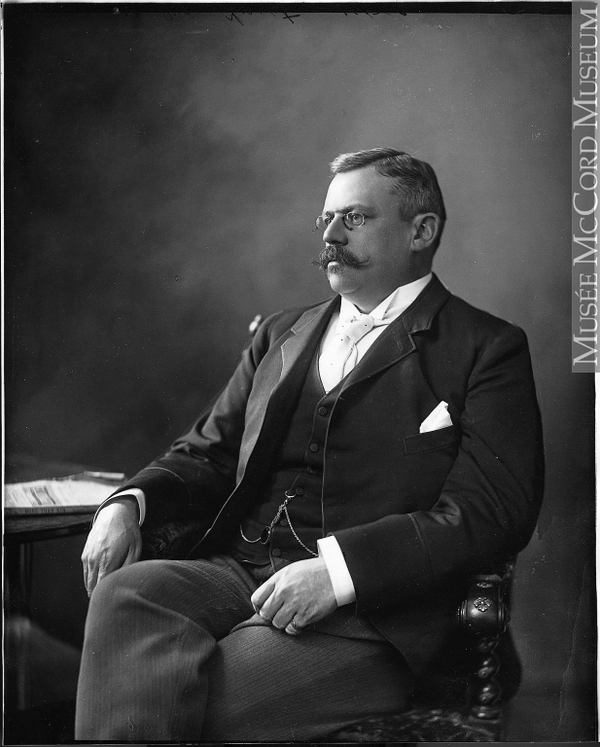

FORGET, LOUIS-JOSEPH, stockbroker, financier, and politician; b. 11 March 1853 in Terrebonne, Lower Canada, son of François Forget, a farmer, and Appoline Ouimet; m. 2 May 1876 Maria Raymond in Montreal, and they had four daughters; d. 7 April 1911 in Nice, France.

A descendant of a family that had arrived in New France from Normandy in the mid 17th century, Louis-Joseph Forget became one of the dominant figures of business and finance in Canada during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was educated at the Collège Masson, Terrebonne, and in 1873 he started working as a clerk in a stockbroker’s firm in Montreal. The following year, at age 21, he raised the necessary funds to purchase a seat on the Montreal Stock Exchange. In 1876 he founded the firm L. J. Forget et Compagnie with his wife, who probably provided the financial backing. Seven years later that assistance was no longer necessary; his wife withdrew from the firm and Forget continued on alone until 1890. L. J. Forget et Compagnie became one of the most important brokerage firms in Montreal and was widely known in financial circles throughout the rest of Canada and abroad. It is said to have been responsible for about 50 per cent of the activity on the exchange. As well as financiers, brokers, and industrialists, its 250 to 300 clients included numerous investors of small sums. By 1892 a Montreal correspondent for the Empire (Toronto) estimated that Forget was one of the 15 wealthiest French Canadians in Montreal, those whose estimated worth was greater than $500,000. In 1895 he was elected chairman of the Montreal Stock Exchange and he was re-elected the following year.

Described by his great-niece Thérèse Casgrain [Forget*] as “calm [and] well-balanced,” Forget was generally considered a cautious speculator who accumulated most of his wealth by initiating mergers of existing enterprises and selling the securities of the newly created or restructured firms. He did not encourage his clients to speculate excessively unless they were prepared to accept risks. In the early years of his brokerage operations, Forget eagerly offered his services to the government of Quebec when it needed to borrow substantial funds. In 1882 he took on half of a loan of about $3,000,000 that was secured by the province. With businessman Louis-Adélard Senécal*, he unsuccessfully attempted to sell the provincial obligations to the financial community in France. Within a year, however, the contract between the Quebec government and Forget’s firm was rescinded and the Bank of Montreal stepped in to assume responsibility for the loan.

In October 1890 Forget took his nephew Rodolphe Forget as a partner in his brokerage business. In marked contrast to his adventurous nephew, Louis-Joseph exercised great prudence in his business ventures. Still, the two men shared a passion for the financial restructuring of companies and, despite their divergent styles, were alleged to have frequently engaged in the overcapitalization of certain enterprises in the hope of realizing quick profits.

Forget would serve on numerous boards of directors, including in 1904 that of the Canadian Pacific Railway, where he was the first French Canadian to be named to the prestigious board. He took his participation in these enterprises seriously and was said to have carefully scrutinized the affairs of the companies over which he presided. He personally prepared meetings of the directors, during which he addressed the members equally well in English or French. That he was so successful in a milieu dominated by Canadians of British descent was a tribute to his skill in transcending linguistic and cultural differences to mobilize effectively his business and political contacts. Where informal networks of politicians and businessmen seemed too difficult for French Canadians to enter, he established his own.

Forget was perhaps best known for his involvement in the development of public utilities at a time when important financial and technological changes were taking place. A director of the Montreal Street Railway Company since 1886, he became its president in 1892. Under his direction the company evolved from horse cars to electric tramways. He and his nephew were said to have conceived the idea of a merger between the tramway, gas, and electrical firms of Montreal. In July 1899 the Forgets, L. J. Forget et Compagnie, and some associates acquired a majority of the shares in the Royal Electric Company, in which the Forgets already had substantial holdings. In assuming control of Royal Electric and an affiliated enterprise, the Chambly Manufacturing Company, the Forgets met with resistance from a group which had interests in both enterprises and was led by a leading financier, Herbert Samuel Holt*. The takeover was perceived as a threat to the cooperative and highly profitable relationship between Royal Electric and Holt’s Montreal Gas Company.

Through the good offices of James Ross, then executive director of the Montreal Street Railway Company, the Forgets invited Holt to participate in the formation of a new firm which would benefit from a monopoly of the various utilities in Montreal. When Holt was offered the presidency of this firm, his conflicts with the Forgets rapidly dissipated. A merger of Royal Electric, Chambly Manufacturing, and Montreal Gas under the name Montreal Light, Heat and Power Company took effect on 25 April 1901. The board of directors included, among others, Ross as first vice-president, Rodolphe Forget (president of Royal Electric) as second vice-president, and Louis-Joseph Forget as a director. The Forgets directed their efforts to the profitable business of selling the securities of Montreal Light in England, Europe, and the United States. With the merging companies exchanging shares in their enterprises for those of Montreal Light, Louis-Joseph Forget emerged as one of the largest single shareholders in the venture. Indeed, in the early part of Montreal Light’s existence, L. J. Forget et Compagnie held the majority of its shares.

Although many contemporary observers credited Rodolphe with the merger, it seems apparent that, without the contribution of his uncle, the varied interests might not have come together. According to numerous financiers, Rodolphe’s ability to realize certain projects was the direct result of the support of his uncle, whose “word is his bond.” Not only was the capital of L. J. Forget et Compagnie a major factor in enacting several such large transactions, but Louis-Joseph’s political contacts were also vital. For example, he played a pivotal role in procuring a charter for Montreal Light. Through his contacts in municipal and provincial politics, he succeeded in obtaining in that charter permission for the company to use Montreal’s streets to install its wires and conduits. With the assistance of Henri-Benjamin Rainville, a former municipal councillor, an mla, and a director of Montreal Light, Forget was able to acquire for the merger a near-monopoly of the public service contracts in Montreal.

The possibility of expanding the supply of electricity had likely led Forget initially to support the development of hydroelectric power at Shawinigan falls. In early 1898 a group of investors formed the Shawinigan Water and Power Company [see John Edward Aldred*]. Forget was a member of the board of directors. In the beginning, the project did not draw sufficient financial support from local banks so Forget contributed $50,000 to help start the firm. It rapidly became apparent, however, that his interest was primarily motivated by the benefits which might accrue to Montreal Light. In March 1902 Montreal Light was prepared to invest significantly in Shawinigan Water and Power, but it was unable to obtain the number of shares it wanted and found Shawinigan’s electricity too costly, so it did not pursue negotiations. Shortly thereafter, Shawinigan Water and Power signed a contract with the Lachine Rapids Hydraulic and Land Company, then a major rival of Montreal Light; Forget resigned immediately from the board of the Shawinigan firm.

Forget’s involvement in mergers was not confined to hydroelectricity; he also organized one in the cotton industry. Large-scale mergers in this sector had already been effected by Andrew Frederick Gault* in 1890 and 1892. At the time of his death in 1903, Gault was working on plans for perhaps the most important merger to date in the industry. In succeeding Gault as president of Dominion Cotton Mills Company Limited, Forget was responsible for finalizing those plans, which resulted in January 1905 in the establishment of the Dominion Textile Company. The new firm included all the holdings of Dominion Cotton, as well as those of the Merchants’ Cotton Company, the Montmorency Cotton Mills Company [see Robert Brodie*], and the Colonial Bleaching and Printing Company, equivalent to over 40 per cent of the total capacity of the cotton sector. In addition, Dominion Textile had close ties to the Montreal Cotton Company.

Yet another achievement was Forget’s management of the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company and its fleet. When he took over the company in 1894, it was in financial difficulty and had not paid dividends to shareholders. On his resignation from the presidency in 1904, it was paying dividends of six percent. His nephew Rodolphe succeeded him as president.

In addition to rivals in business and politics, Forget had some detractors. The Forgets were frequently in conflict with labour unions. Transportation by tramway had certain imperfections. When accidents occurred, the victims were described as having been subjected to “Forget’s crushers.” In February 1903 tramway workers in Montreal went on strike for the first time in order to obtain recognition of their union and increases in wages. They obtained both quickly but three months later, after the company had refused to recognize their affiliation to an international union, they walked out again. The presence of strikebreakers provoked violence; workers at Montreal Light stopped work in sympathy, plunging sections of the city into darkness. Public opinion and the press increasingly denounced the strike, as did church leaders. By 28 May the tramways were running again. Forget would have to face other labour disputes, especially at Dominion Textile in 1906 and 1908 [see Wilfrid Paquette].

Forget maintained important contacts with politicians at all levels of government. Although he was an active member of the Conservative party, his brokerage and commercial operations transcended party lines. Indeed, provincial Liberal premier Lomer Gouin*, Liberal mp Rodolphe Lemieux*, and Liberal prime minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier were all privileged clients of L. J. Forget et Compagnie.

In the early 1890s Forget had been attracted to electoral office. In 1892 Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau* was successful in persuading him to contest the federal election in the riding of Jacques-Cartier. A late intervention by his wife, Maria Raymond, led him to back down. Still, Forget did not abandon his interest in political office. Given his connections with the federal Conservatives, particularly through his fundraising activities, he expected to be named to the Senate. Ultimately, however, it was his business interests that played the dominant role in his appointment. His nomination in 1896 was in large part linked to his contacts in Sorel and notably to his involvement with the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company, based in that city. From 1867 to 1896 the senator for Sorel, Jean-Baptiste Guévremont, had sought and obtained the assistance of Forget to resolve his severe problems of debt. Guévremont retired in June 1896 and the Conservative government moved just in time to name Forget to the Senate before its defeat in the federal election later that month. Forget’s participation in the deliberations of the Senate would be relatively infrequent.

With the federal Conservatives in disarray after their electoral defeat, reorganization of the party was considered essential. Forget played a central role in rebuilding Conservative support, particularly in Quebec. One of his first major initiatives was the creation in 1899 of a new French-language newspaper in Montreal, owned and controlled by a group of important Conservatives, including himself and financier Louis Beaubien. Le Journal was to supplement the lukewarm support offered by La Presse [see Trefflé Berthiaume], but it got off to a difficult start and throughout its brief existence never seemed to get on track. When it folded in March 1905, its losses were estimated at $80,000, the bulk of which was said to have been absorbed by Forget.

Following his election to the House of Commons in 1904, nephew Rodolphe was increasingly uncomfortable working under the tutelage of his uncle and he expressed a growing desire to conduct his own affairs. A dispute between him and Jack Ross, son of Louis-Joseph’s long-time colleague James Ross, had significant repercussions, harming the relationship between the elder Forget and Ross. At the same time, relations between uncle and nephew also eroded to a point where on 1 Aug. 1907 their partnership was dissolved. Louis-Joseph continued L. J. Forget et Compagnie with Thomas W. McAnulty, who had become a partner in the firm eight months earlier. McAnulty would continue the company under the same name for years after Forget’s death. While most of the firm’s clientele were divided between the two Forgets, a certain number of investors placed their holdings elsewhere rather than have to choose between uncle and nephew.

Having lost his partner of 17 years, Forget was rendered all the more vulnerable because of the economic crisis of 1907, which caused major problems for a number of his investments. Some of the larger enterprises, such as the Montreal Street Railway Company, were particularly affected. Forget presided over a reorganization of the company in the light of an attempted take-over by his colleague-turned-rival, James Ross. Although he had been successful in defeating an earlier bid by Ross on his interests in the Dominion Iron and Steel Company Limited, his ability to prevent Ross’s assault on the Montreal Street Railway was hindered by the severe heart problems he experienced that year. For reasons of health, he took his family to Europe in 1908. In England he attended a session of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council on the dispute between the Dominion Iron and Steel Company Limited and the Dominion Coal Company Limited which confirmed his victory over Ross. In the summer of 1908, as his health deteriorated, he decided not to pursue the battle with Ross for control of the Montreal Street Railway. In the fall of 1909 he gave up the presidency of the company and was replaced by Edmund Arthur Robert*.

Although a charitable person, Forget preferred not to receive publicity about his donations. He was respectful of religious authority and gave generously to the Roman Catholic archdiocese of Montreal. One of his main interests was the Montreal branch of the Université Laval. When Archbishop Édouard-Charles Fabre* contemplated the creation of a board of governors to look after the “material” interests of the university, he invited Forget to accept the presidency. Forget was to occupy various positions on the board until his death and would bequeath a chair to the university.

Louis-Joseph Forget died in France at age 58. His estate was valued at more than $4,000,000. He was survived by his wife and four daughters. The day after he died, a Montreal newspaper described him as “one of the colossal figures about whom have surged the tides and currents of Canadian finance.” It emphasized that the senator was known for his “absolute unswerving fidelity to his word,” and concluded that “in all the heat and confusion of the stock market amidst the treacheries which sometimes attend on high financing and the deception and duplicity which beset the path of the successful man everywhere, there was never a question of his own unfaulty veracity.”

AC, Montréal, Cour supérieure, déclarations de sociétés, 7, no.1324 (1876); 10, nos.1138–39 (1883); 15, no.470 (1890); 27, nos.23 (1907), 603 (1907), 616–17 (1907); 32, no.384 (1911). ANQ-M, CE1-51, 2 mai 1876; CE6-24, 11 mars 1853. Claude Bellavance, Shawinigan Water and Power, 1898–1963: formation et déclin d’un groupe industriel au Québec ([Montréal], 1994). The Canadian parliament: biographical sketches and photo-engravures of the senators and members of the House of Commons of Canada (Montreal, 1906). E. A. Collard, Chalk to computers: the story of the Montreal Stock Exchange ([Montreal], 1974). CPG, 1897–1911. J. H. Dales, Hydroelectricity and industrial development: Quebec, 1898–1940 (Cambridge, Mass., 1957). Thérèse F[orget] Casgrain, A woman in a man’s world, trans. Joyce Marshall (Toronto, 1972). [Jacqueline] Francœur, Trente ans rue St-François-Xavier et ailleurs (Montréal, 1928). Clarence Hogue et al., Québec: un siècle d’électricité (Montréal, 1979). A. B. McCullough, The primary textile industry in Canada: history and heritage (Environment Canada, National Historic Sites, Parks Service, Studies in Archaeology, Architecture and Hist., Ottawa, 1992). T. D. Regehr, “A backwoodsman and an engineer in Canadian business: an examination of a divergence of entrepreneurial practices in Canada at the turn of the century,” CHA, Hist. papers, 1977: 158–77. Rumilly, Hist. de la prov. de Québec, vols.3–4, 6–16. Marc Vallières, “Le gouvernement du Québec et les milieux financiers de 1867 à 1920,” L’Actualité économique (Montréal), 59 (1983): 531–50.

Cite This Article

Jack Jedwab, “FORGET, LOUIS-JOSEPH (baptized Louis),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed October 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/forget_louis_joseph_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/forget_louis_joseph_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jack Jedwab |

| Title of Article: | FORGET, LOUIS-JOSEPH (baptized Louis) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | October 21, 2025 |