Source: Link

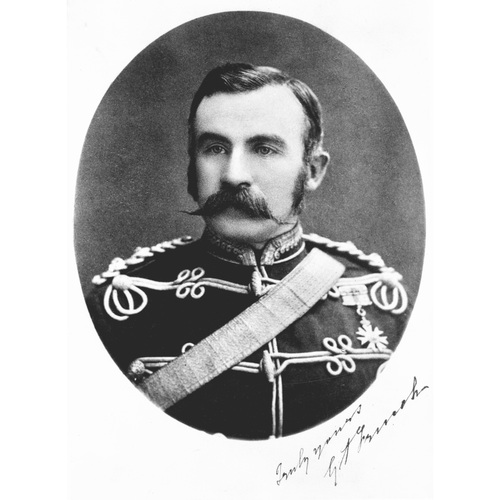

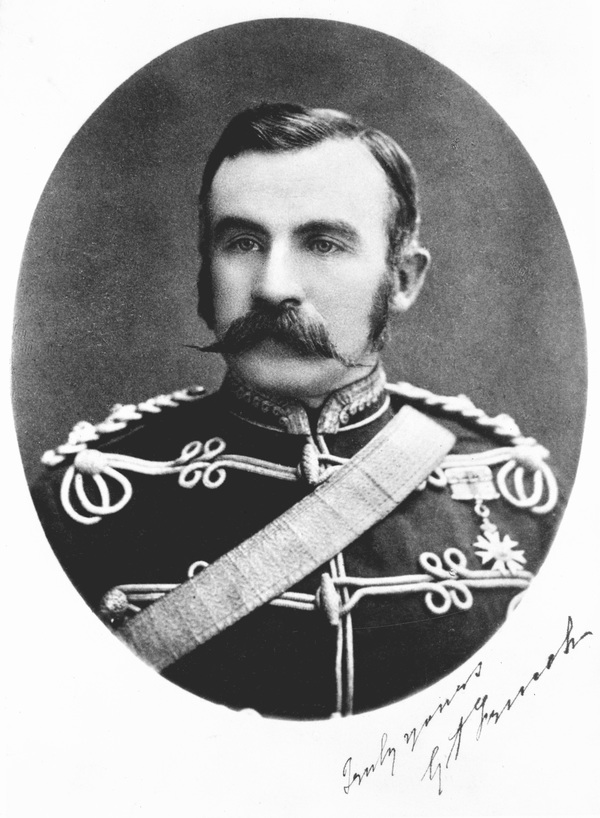

FRENCH, Sir GEORGE ARTHUR, army, militia, and NWMP officer; b. 19 June 1841 in Roscommon (Republic of Ireland), eldest son of John French and Isabella Hamilton; m. 18 Dec. 1862 Janet Clarke Innes (d. 1917) in Kingston, Upper Canada, and they had two sons and three daughters; d. 7 July 1921 in Kensington (London), England.

George Arthur French was Anglo-Irish, like so many other British army officers of the late 19th century. The fact that he started his military education at Sandhurst, but transferred to the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich (London) and became a gunner, suggests that his family was not well-to-do. Commissions in the Royal Artillery were not purchased as were those in infantry and cavalry regiments.

Appointed a lieutenant on 19 June 1860, French served with the RA in Kingston from 1862 to 1866. In 1869 he was seconded to the Canadian militia as inspector of artillery and warlike stores; though promoted lieutenant-colonel, a rank he would not achieve in the army until 1 Oct. 1887, he probably accepted the move as much for monetary as for career considerations. Conscious of the withdrawal of the imperial forces from Canada, French urged on the Department of Militia and Defence, in his report of 1 Jan. 1870, “the absolute necessity of raising, permanently, a few batteries of garrison artillery.” To his recommendation he appended estimates for two batteries. In response the department moved to establish permanent schools of artillery in Kingston and Quebec City for training the militia. While retaining his inspectorship, French was authorized on 20 Oct. 1871 to set up and command Kingston’s School of Gunnery (A Battery, Garrison Artillery).

When the government of Sir John A. Macdonald* created the North-West Mounted Police in 1873, the choice of who would be its first commissioner was of the utmost importance. There was no shortage of applicants, among them Thomas Bland Strange, commandant of the Quebec artillery school, and several senior militia officers. Macdonald’s reasons for choosing French are not on record, but as Kingston’s mp, he could hardly have avoided meeting this competent commander. As well, French had served briefly in the Royal Irish Constabulary before entering the army and since it was an important model for the NWMP, his experience may have influenced Macdonald’s decision.

Although French took over as commissioner on 16 Oct. 1873, his duties in Kingston did not end until after the end of November. By then the NWMP was already partially in existence. News of the massacre in the Cypress Hills (Alta/Sask.) of Hunkajuka* and some of his followers by a band of Canadian and American traders and hunters had forced the government to advance its timetable; 150 recruits and several officers, among them James Farquharson Macleod*, had been sent to Winnipeg, where they had begun training under William Osborne Smith*. After visiting Winnipeg in January 1874 to assess his command, French returned to Toronto to raise a second contingent.

French, 16 officers (including his brother John*), 201 men, and 244 horses boarded special trains on 6 June and travelled west through Chicago to Fargo (N.Dak.). From there they rode north to Dufferin, Man., where they met the group who had wintered in Winnipeg. French’s instructions were to take his force west to what is now southern Alberta and stop the whisky trade being conducted from the Montana Territory. The plan for the journey, which became known as the Long March, was to follow a route just north of the 49th parallel in order to take advantage of the camps and caches established by the international boundary surveyors [see Samuel Anderson*], but reports of fighting near the border between natives and the United States army caused Ottawa to order French to stay well north.

The change created serious difficulties for the NWMP. The only available map of the region, prepared by John Palliser*’s expedition of 1857, turned out to be inaccurate; guides could not be found; and the police were unable to locate feed and water for their horses. At the end of July, nearly a month after the march had begun, French sent a troop and the sickest horses north along the Carlton Trail to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Edmonton (Edmonton). The rest moved on across the trackless prairie; by early September it was apparent to most that French had no idea where they were. He did not lose his nerve, however, and kept pushing his weary men westward until they reached recognizable territory. On 18 September they halted and established a camp in the Sweet Grass Hills (Alta/Mont.).

French took a party south to Fort Benton (Mont.) to obtain horses and supplies and to telegraph Ottawa. He also gathered evidence about the Cypress Hills massacre. The government approved his plan to leave most of his force in the Belly River area while he trekked northeast to establish headquarters at Swan River (Livingstone, Sask.). The site, chosen in Ottawa because of its location on the proposed rail line to the Pacific coast, had little else to recommend it, as French discovered when he arrived on 21 October. It was not close to any major concentration of native people, nor was there any settlement in the area. Moreover, the barren locale had been swept by fire and the contractors had not completed the buildings. Convinced that it would not be possible to get all his men and horses through the winter there, French left about 30 men behind and, though he had no jurisdiction in Manitoba, wisely moved his headquarters south to Dufferin.

When French returned to Swan River in the spring of 1875, he loyally tried to make it habitable. In his correspondence with Ottawa, he nonetheless made no secret of his negative opinion of the post and lobbied strenuously to have his headquarters moved to Fort Macleod (Alta), where most of the force’s actual policing was centred. Unfortunately for French, the political climate as it affected the NWMP had changed following the formation of a Liberal government in late 1873. The new prime minister, Alexander Mackenzie*, was exceedingly parsimonious and he and his cabinet harboured grave doubts about the wisdom of creating the NWMP in the first place. A Conservative appointee, French was unlikely to receive a sympathetic hearing. Moreover, the fact that he had many suggestions for improving the force, all expensive, confirmed the government’s suspicion that he was a profligate.

By early 1876 the situation had become acute. Aware that he no longer had the confidence of the government, French attempted to bring matters to a head. In March he wrote to the minister of justice, Edward Blake*, asking for permission to travel to Ottawa to discuss a host of pressing problems. Permission was refused. In an exchange of telegrams over the next two months, he kept advancing reasons to visit the capital, but his political masters kept denying his requests. When he offered to pay for the trip and still was turned down, he knew his position was untenable. He resigned in July 1876. His officers and men showed a greater appreciation of his work: they gave him a gold watch worth $150 (a large sum for the time) and Mrs French a silver service. The British government also recognized his efforts, with a cmg on 30 May 1877.

French went back to postings with the Royal Artillery in England, interspersed with appointments in Australia and India. He was inspector of warlike stores at Devonport from 1878 until he became commandant of the colonial forces in Queensland in 1883. In 1885 the defence force there was reorganized under legislation drafted by French and based on Canada’s system. On his return to England in 1891, he was put in command of the RA at Dover. From June 1892 to October 1893 he served as a chief instructor at the School of Gunnery in Shoeburyness. He then spent two years as a staff colonel commanding the RA in Bombay. His last appointment was as commandant of the colonial forces in New South Wales. Promoted major-general on 25 May 1900, he retired from the army in September 1902 and was made a kcmg that year. He lived in London until his death.

A moderately distinguished army man, French played an important, if brief, role in the history of Canada. He helped facilitate the creation of a permanent defence force. As the first permanent commissioner of the NWMP, he organized it and got it firmly established in the west, but the difficulties involved and the lack of political support from the Mackenzie government led to his early resignation and departure from Canada.

AO, RG 80-27-2, 10: 4. NA, RG 18. Times (London), 8, 11, 13 July 1921. Australian dictionary of biography, ed. Douglas Pike et al. (14v. and index to date, Melbourne, 1966– ). Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1871, no.7: 123–31; 1872, no.8: 86–95; 1874, no.7: 37–39, 49–51. Canada Gazette, 21 Oct. 1871: 343–46. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Debrett’s peerage, baronetage, knightage, and companionage . . . (London), 1920. G.B., War Office, The official army list (London), 1882, 1910. Hart’s annual army list . . . (London), 1874, 1893–95, 1901. R. C. Macleod, The NWMP and law enforcement, 1873–1905 (Toronto, 1976). G. W. L. Nicholson, The gunners of Canada; the history of the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery (2v., Toronto, 1967–72), 1. H. P. Noble, “The commissioner who almost wasn’t,” RCMP Quarterly (Ottawa), 30 (1964–65), no.2: 9–10. J. P. Turner, The North-West Mounted Police, 1873–1893 . . . (2v., Ottawa, 1950), 1.

Cite This Article

Roderick C. Macleod, “FRENCH, Sir GEORGE ARTHUR,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/french_george_arthur_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/french_george_arthur_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Roderick C. Macleod |

| Title of Article: | FRENCH, Sir GEORGE ARTHUR |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | May 24, 2025 |