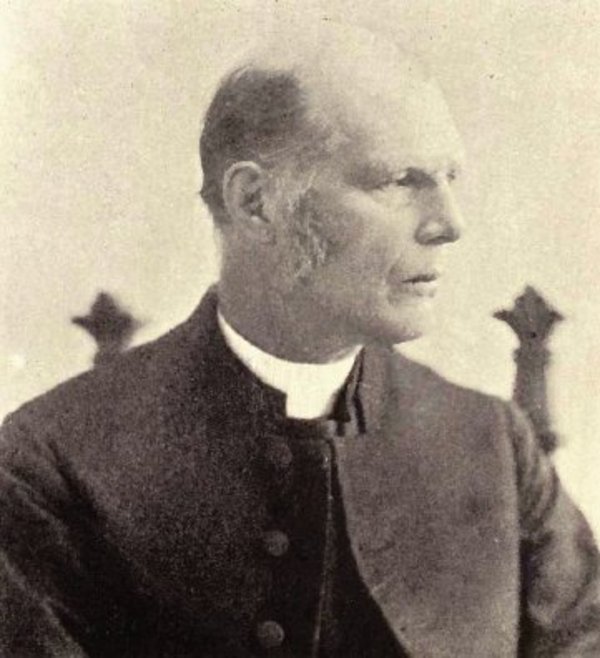

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

BALDWIN, MAURICE SCOLLARD, Church of England clergyman, bishop, and author; b. 21 June 1836 in Toronto, fourth son of John Spread Baldwin and Anne Shaw; m. first 4 Sept. 1861 in St Thomas, Upper Canada, Maria Ermatinger (d. 1863), and they had a daughter; m. secondly 21 April 1870 Sarah Jessie Day, and they had three daughters and a son; d. 19 Oct. 1904 in London, Ont.

Maurice Scollard Baldwin was related to two prominent Toronto families: his maternal grandfather was Æneas Shaw*, William Warren Baldwin* and Augustus Warren Baldwin* were uncles, and Robert Baldwin* was a cousin. He was educated in Toronto at Upper Canada College and at Trinity College (ba 1859, ma 1862, dd 1882), where his predilection for Methodist-style cottage meetings and salvation sermons raised eyebrows. Because of his evangelicalism he was reportedly refused ordination by Bishop John Strachan* of Toronto. Baldwin began his professional ministry instead in the diocese of Huron, in the southwest part of the province, one of the energetic, evangelical clergy with whom Bishop Benjamin Cronyn* surrounded himself. Cronyn ordained him deacon in 1860 and priest in 1861, and appointed him curate of St Thomas’ Church in St Thomas (1860–62). Baldwin served incumbencies at Port Dover (1862–63, 1864–65) and Port Stanley (1863–64) before being called to Montreal. As rector of St Luke’s, Montreal (1865–70), he built a reputation as the city’s greatest anglophone preacher. Next called to Christ Church Cathedral (junior curate 1870–72, rector 1872–83, dean 1882–83), he was at the centre of controversy in 1874 when he resisted Bishop Ashton Oxenden*’s assertion of episcopal rights over the cathedral. In the end, Baldwin helped negotiate the “Montreal agreement,” which defined the boundaries between the jurisdictions of the bishop and the cathedral’s congregation.

When Isaac Hellmuth resigned as bishop of Huron, the diocesan synod elected Baldwin his successor in 1883. He aimed to devote his efforts “first and chiefest of all,” as he told synod five years later, to “the spiritual life of the Diocese.” Contemporaries indeed knew him as “the most spiritually minded” of Canada’s Anglican bishops, in the words of the London Free Press. He routinely preached three times a Sunday, frequently spoke every evening of the week in parish churches, and led numerous retreats for clergy, deaneries, and other groups. Characteristically he attributed most of the problems of the church to insufficient faithfulness. He regretted the tendency to base ecclesiastical decisions on business principles, as if the major question should be “What will make it pay?” Baldwin was a keen advocate of domestic and foreign missions, Sunday schools, and temperance, and a supporter of the contemporary movement for ordaining deaconesses.

Although his heart was not in administration, he was able to identify administrators and make use of them. During his episcopate, Huron, like other dioceses at the time [see Arthur Sweatman], developed modern procedures of governance, fund-raising, and accounting. The deficit that Baldwin had inherited became a surplus, and by 1887 Huron was able to become the first Anglican diocese in Canada to guarantee minimum stipends for clergy. One casualty of the balanced budget was the project begun by Hellmuth for a new diocesan cathedral. Baldwin terminated it in 1887 and restored cathedral status to St Paul’s, London, making the “Montreal agreement” the basis for distinguishing its cathedral from its parish qualities.

Baldwin also gave his synod a greater role in diocesan governance than Hellmuth had allowed it. In 1885 it had adopted rules of order modelled on the House of Commons, perhaps the only Christian deliberative body in Canada ever to do so, and the level of debate was reputed to be the highest in Canadian Anglicanism. Huron was the first synod to pass a resolution, in 1886, calling for the amalgamation of the Church of England in Canada from sea to sea, and in 1902 it organized the first Anglican Young People’s Association, which became a prominent denominational institution.

It was a particular goal of Baldwin to give his diocese a distinctly Canadian character. Himself its first native-born bishop, he preferred to recruit Canadian rather than British clergy. He was stung by experiences such as the resignation in 1890 of a British principal of Huron College, Richard Gooch Fowell, who “does not like Canada or, more correctly speaking, the Canadians.” On that occasion he petitioned the English patron of the college, the Reverend Alfred Peache, to appoint a Canadian to be the next principal, but he was unsuccessful.

Contemporaries knew Baldwin primarily as a preacher, one of the greatest evangelical speakers of his day. His printed sermons reflect the skills of the preacher’s art: clear construction, vivid language, engaging illustrations, humour, topical appeal, and, above all, earnest devotion to Scripture. His delivery was particularly powerful. The Reverend Dyson Hague recalled Baldwin’s “hammer of emphasis,” his intensity, and “a cadence, a musical interest, . . . that held one fascinated to the very climax.” Few contemporary Canadian preachers were in such demand, nationally and internationally.

As president of the council of Huron College, Baldwin wielded considerable influence on the affairs of Western University of London, Ontario. Historians James J. and Ruth Davis Talman have argued that his policies towards Western were “vacillating.” In 1884–85 he diverted the Good Friday collections of the diocese from the college to other purposes, prevented Hellmuth from continuing as chancellor, and withdrew Huron from its affiliation with Western, virtually forcing the university to suspend teaching in the arts. On the other hand, in 1891 he helped raise funds for the university, and in 1895 he restored Huron’s affiliation and revived the faculty of arts. Baldwin’s change of heart may reflect a change in circumstances rather than mood. In 1884 it seemed possible that struggling Huron might be allowed to affiliate with the thriving University of Toronto. When that option was excluded by the university federation act of 1887 and as the diocese improved its financial situation, Baldwin gave his support to the local university. The Talmans have also questioned his interest in education, but Baldwin himself was something of an academic: he read biblical Greek and Hebrew, lectured in theology at Huron, and published an essay on the principles of biblical translation.

Baldwin died in 1904 after suffering a paralytic stroke, and was buried in St James’ Cemetery, Toronto. He had been a mentor and a model when the Canadian Protestant evangelical program was at its height, ecumenically recognized as an inspiring preacher and as an effective evangelistic author. Within Anglicanism, the low-church party promoted him, both before and after his death, as a paradigm of the Protestant pastor. He was noted above all, in the language of the day, for his “earnestness” – his committed faith, spiritual values, personal humility. It is less important to note that his lasting contribution to thought, policy, and administration was a modest one.

Seven of Maurice Scollard Baldwin’s published works have been made available on microfiche by the CIHM and are cited in its Reg., including Correspondence between the Most Rev. the Metropolitan and the Rev. the Rector of the parish of Montreal (Montreal, 1874), which documents his 1874 dispute with Oxenden. Baldwin’s annual reports to synod are printed in Church of England in Canada, Diocese of Huron, Journal of the synod (London, Ont.), 1883–1904; those for 1883–93 have been filmed by the CIHM.

The ACC, Diocese of Huron Arch., located in Huron College (London), holds two letter-books and a few other records of the diocese during Baldwin’s episcopate. A favourable biographical recollection is Dyson Hague, Bishop Baldwin, a brief sketch of one of Canada’s greatest preachers and noblest church leaders (Toronto, 1927).

Some sources give 1879 as the date when Baldwin became dean of Montreal; the correct date is supplied in the Evangelical Churchman (Toronto) of 22 June 1882 and the Journal of the Montreal synod (cited below).

ACC, Diocese of Huron Arch., Bishops’ letter-books, 1890–1917, esp. 8 March, 9 April 1890; Executive committee, minutes. AO, F 980, MU 4952 [includes two brief, unhelpful letters]; RG 22, ser.321, no.8130. NA, RG 31, C1, 1891, London, Ward 2: 16 (mfm. at AO). Daily Mail and Empire, 20 Oct. 1904. Globe, 20 Oct. 1904. London Free Press, 20 Oct. 1904: 6. Toronto Daily Star, 20 Oct. 1904: 9. Canadian Churchman, 27 Oct. 1904: 645–46. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Chadwick, Ontarian families, vol.2. Church of England, Diocese of Montreal, Journal of the synod, 1872–82. Church of England in Canada, Diocese of Huron, Journal of the synod, 1883–1905, esp. 1888: 27; 1897: 22. J. C. Farthing, Recollections of the Right Rev. John Cragg Farthing, bishop of Montreal, 1909–1939 (Toronto, 1945). In memoriam Maurice S. Baldwin, third bishop of Huron ([London, 1904?]; copy at ACC, General Synod Arch., Toronto). A jubilee memorial: the story of the church and first fifty years of the diocese of Huron, 1857–1907 (London, [1907]; copy at ACC, General Synod Arch.). Souvenir of the Right Rev. Maurice S. Baldwin, D.D., bishop of Huron (Montreal, 1884). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). J. J. Talman, Huron College, 1863–1963 (London, 1963). J. J. Talman and Ruth Davis Talman, “Western” – 1878–1953: being the history of the origins and development of the University of Western Ontario during its first seventy-five years (London, 1953).

Cite This Article

Alan L. Hayes, “BALDWIN, MAURICE SCOLLARD,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed July 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baldwin_maurice_scollard_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baldwin_maurice_scollard_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Alan L. Hayes |

| Title of Article: | BALDWIN, MAURICE SCOLLARD |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | July 14, 2025 |