Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

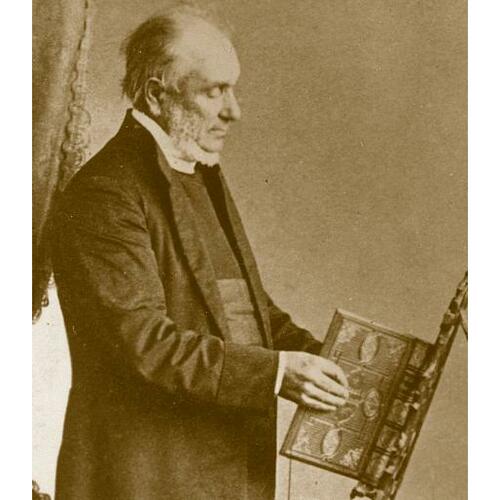

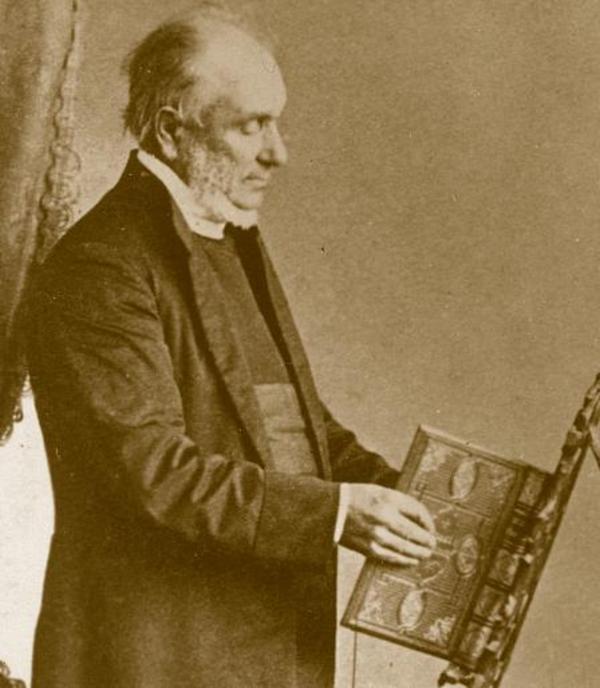

CRONYN, BENJAMIN, Church of England clergyman and first bishop of Huron; b. at Kilkenny, Ireland, 11 July 1802, son of Thomas Cronyn, of Kilkenny, and Margaret Barton; d. at London, Ont., 21 Sept. 1871.

Benjamin Cronyn was educated at Kilkenny College, and at 15 entered Trinity College in Dublin where he received his ba in 1822, ma in 1825, and, later, dd in 1855. He was divinity prizeman in 1824. In 1825 he was ordained deacon and served as curate at Tunstall, Kirkby Lonsdale, in Lancashire, England, until 1827 when he was ordained priest. He was then curate until 1832 of Kilcommock, Longford, in the diocese of Ardagh, Ireland.

In 1832 the archbishop of Dublin wrote to Archdeacon John Strachan* in York (Toronto) inquiring about openings in Canada for Protestant clergymen who “are thinking of emigration from finding themselves destitute thro’ the existing troubles of the Church.” Cronyn and his family were among the many Irish Protestants who decided to emigrate to Upper Canada. They sailed in the summer of 1832 on the Anne of Halifax chartered by a group of friends. Among them were Anne Margaret Hume, widow of the Reverend Dominick Edward Blake of County Wicklow, with her two sons, the Reverend Dominick Edward and William Hume*, and her daughters Frances Mary and Wilhelmina, wife of the Reverend Charles Crosbie Brough.

Cronyn had married in Ireland Margaret Ann Bickerstaff of Lislea, Longford, in December 1826. Of their seven children, Margaret married Edward Blake*, son of William Hume Blake; Verschoyle married Edward’s sister, Sophia; Rebecca married Edward’s brother, Samuel Hume Blake*; Benjamin married Mary G. Goodhue, daughter of George Jervis Goodhue*. Margaret Ann Cronyn died 29 Oct. 1866, and Benjamin was married again at Dublin, Ireland, on 16 March 1868, to Martha Collins; there were no children from this marriage.

Arriving in York, Cronyn met Strachan and Bishop Charles James Stewart* of Quebec, who licensed him to Adelaide. This township was then being settled by many of Cronyn’s Irish friends, and there had apparently been an understanding that Cronyn would minister to them. On their way to Adelaide in November, Cronyn and his family were overtaken by darkness in London. He preached there on the following day, and, so effective was his sermon, he was persuaded to remain. Stewart subsequently authorized the change, appointing Cronyn to London and parts adjacent and Dominick Blake to the Adelaide charge.

London at this time was a settlement six years old. The Reverend Benjamin Lundy, a pioneer abolitionist, visited the village in 1832, and told of the recently finished court house, two houses of public worship being built, three hotels, and six general merchant stores; he enumerated its variety of craftsmen, who were necessary in a new community. He estimated that there were about 130 buildings, nearly all frame, in the village. There were two doctors and two lawyers, and one weekly newspaper, the Sun. By this time there were Methodist, Presbyterian, and Church of England congregations in the community, which had a population of about 300.

One of Cronyn’s first actions was to move and complete, during the winter of 1832–33, the unfinished church building begun by his predecessor, the Reverend E. J. Boswell. This had been erected on an unsatisfactory site and he located St Paul’s Church (which burned in 1844 but was rebuilt in 1846) where St Paul’s Cathedral now stands. Cronyn held services in London and at various stations in London Township. His son, Verschoyle, wrote that he was a “fearless horseman” and “expert swimmer,” necessary attainments for travelling in his extensive field.

Under the terms of the Canada Act of 1791, the British government had power to authorize the erection of rectories in the province endowed with glebe lands. Implementation was delayed until 1836 when Sir John Colborne*, acting on an 1832 dispatch from the colonial secretary, Lord Goderich, ordered the preparation of patents setting up 57 rectories (Colborne actually signed only 44 before leaving the colony). Both London and London Township were among the rectories established. Cronyn thus held and received the income from two rectories, the only clergyman in Upper Canada to do so. He gave up the township rectory (now St John’s, Arva) in 1841. In 1838 he was able to augment his income by taking on the duties of chaplain at London: the War Office had deemed it expedient in 1832 to discontinue the appointment of chaplains to the forces at certain Canadian posts and to employ a resident “Clergyman of the Established Church.” (When Archdeacon Alexander Neil Bethune preached in St Paul’s in 1848, the military constituted most of the congregation.)

Support from overseas for the church in Upper Canada was vital in these years, and in January 1837 Cronyn accompanied William Bettridge to England to solicit aid. They separated in July when Cronyn went to Ireland to deal with family affairs and to carry on there the campaign for men and money.

The population in the western parts of Upper Canada increased rapidly and by 1847 it was clear that the diocese of Toronto should be divided. Legal and financial obstacles stood in the way. Strachan took the lead in overcoming the former, by obtaining an act in 1857 which resolved any doubt as to the right of the Canadian church to meet in synods to elect bishops rather than having appointments made from England. Cronyn took care of finance. With other clergy and laity in the western part of the diocese, he organized an episcopal fund committee which raised the £10,000 endowment stipulated by the crown, and he must be given credit for the success of this campaign. With all barriers removed, the synod of Toronto met on 17 June 1857 to set up the present diocese of Huron (a name chosen and applied by Strachan in May), comprising the 13 counties in the southwestern part of the province.

The choice of a bishop precipitated an unseemly, if not scurrilous and libellous, controversy in the pages of the London Free Press and other newspapers of the region (the documents were reprinted in a pamphlet a few days before the election). The names of A. N. Bethune and Cronyn were put forward, and lines were drawn between high and low church. Bethune, the candidate favoured by Strachan, was challenged for his support of Puseyism and Tractarianism and tenets which led “downward to Rome”; Cronyn was identified with “Calvinistic cliqueism.” The theological arguments degenerated into a personal attack on Cronyn, who was accused of neglect of his duties to his parishioners, to prisoners in the jail, and to the troops when he was chaplain. He was also accused of being a speculator in land and “an appropriator to his own use, of the property of his parish.”

Cronyn had, it is true, taken on many responsibilities in his early days in London. He ministered to those who had been condemned to death for their part in the events of 1837–38, and the troops of the garrison attended his church while stationed in London. How far he carried out the other duties associated with the work of a chaplain cannot be shown. His land transactions were complicated, profitable, and, according to some, devious. In a letter to the London Free Press the churchwardens of St Paul’s discussed the accusations, and strongly claimed that church welfare rather than speculation was his motive in negotiations over land which later became valuable.

On 8 July 1857 the delegates met in St Paul’s Church. There were 42 clergy licensed in the 39 parishes in the new diocese, and two laymen from each parish (with one vote; if they did not agree they would not vote). Bishop Strachan presided over the election, which resulted in 22 of the clergy and 23 of the laity voting for Cronyn, and 20 clergymen and ten laymen for Bethune. Six parishes had not voted, presumably because the two lay delegates could not agree. Thus Cronyn was elected on the first ballot.

Many explanations of the result have been given. The clerical vote was greatly influenced by the number of Irish clergy serving in the new diocese. Of the 42 clergy voting, nine were Trinity College, Dublin, men, and at least another six had been born in Ireland or had an Irish background. The low church Irish clergy had more sympathy for Cronyn’s religious views than those of Bethune. Furthermore, the endowment had been raised locally, and the lay contributors also preferred the churchmanship of Cronyn whom they knew and who had led the campaign for funds.

Cronyn was consecrated at Lambeth on 28 Oct. 1857 by the archbishop of Canterbury acting under Queen Victoria’s mandate, the last Canadian bishop required to go to England for consecration. He also visited Ireland where he recruited Edward Sullivan*, later bishop of Algoma, James Carmichael, later bishop of Montreal, and John Philip DuMoulin, later bishop of Niagara. After his return he was enthroned in St Paul’s Cathedral on 24 March 1858.

In his charge delivered to the clergy of the diocese at his first visitation in June 1859, Cronyn told something of his activities as bishop: “Since April, 1858, I have visited eighty-four congregations in the Diocese, and preached 130 sermons; I have confirmed 1,453 candidates, consecrated five churches and two burial grounds, ordained fifteen Deacons and three Priests, and travelled in the discharge of these duties 2,452 miles.” At the same time he made clear his evangelical views. He emphasized the importance of preaching, saying that “Amongst the many means of grace which God has appointed in the Church . . . the preaching of the word stands pre-eminent. The pulpit is the Ministers’ great battle-field.” He condemned “auricular confession and priestly absolution,” “penances and self-inflicted torments,” and “purgatory, with its thousands of years of torment,” stressing instead the need of conversion. The 39 Articles to him were the “ultima ratio in all questions of doctrine,” and “where any of our formularies are expressed in ambiguous language and appear inconsistent with the plain statements of the articles, we are bound to interpret the former by the latter.”

His evangelical views soon involved him in a serious difference of opinion with Strachan. In 1858 some graduates of Trinity College in Toronto, a college instituted by the bishop, expressed views concerning the character and doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church which disturbed Cronyn. He concluded that these views were traceable to the teaching they had received. In April 1860 he wrote to Strachan expressing his disapproval of the college “in many things” and declined to nominate the five councillors whom he had the right to name. At the June 1860 synod of Huron one of Cronyn’s own clergy, the Reverend Adam Townley of Paris, proposed a resolution which stated in part: “this Synod respectfully requests the Lord Bishop [Cronyn] to adopt such means as in his wisdom he may see good as shall tend to secure the hearty co-operation of all Churchmen in support of Trinity College, Toronto.” A lay representative asked Cronyn to give his opinion on the motion and he replied that he could not approve of it: “I think it dangerous to the young men educated there, more particularly if they are educated for the ministry.” He also said that he would not for any consideration send a son of his to the institution nor could he see any prospect of effecting a change in the teaching there.

In a pastoral letter in July 1860 Cronyn gave his recollection of what he had said at the June synod of that year, and attacked “The Provost’s Catechism” which he claimed was placed in the hands of every student entering Trinity College. The views put forth in the catechism were to him “unsound and un-Protestant” and dangerous in the extreme. This attack launched a lengthy controversy between Cronyn and Provost George Whitaker* of Trinity College, which was fully canvassed by the press and in many pamphlets. The Corporation of Trinity College eventually submitted the documents in the dispute to the bishops of the church in British North America, requesting them to declare whether they found any of the doctrines of the provost “unsound or unscriptural, contrary to the teaching of the Church of England, or dangerous in their tendency, or leading to the Church of Rome.” The judgement of the bishops, with Cronyn dissenting, was that several of the points in the provost’s teaching had reference to matters about which the church is silent, but which a theological professor might well discuss. Such statements, however, were private opinions.

Cronyn’s distrust of Trinity College, as well as the urgent need for more clergy in his diocese, had suggested to him the desirability of establishing his own college in which young men might be trained for the ministry under his eye. In his charge to the synod in 1862 he admitted that he had entertained the idea for some time. In 1863 there were only 76 clergy in the diocese and more than 50 townships were without the ministrations of a clergyman. The need for a theological college was clear.

He had already secured in 1861 the services of Dr Isaac Hellmuth*, a man ideally suited for his purposes, to solicit aid in England for the erection of his projected school of theology. In 1862 Hellmuth persuaded the wealthy Reverend Alfred Peache of Downend, Bristol, to contribute £5,000 as an endowment for a divinity chair in the new college, to be called the “Peache chair.” The appointee, the first being Hellmuth himself, was required to “be a Clergyman of the United Church of England and Ireland of strictly Protestant and Evangelical principles and of approved learning ability piety and holiness of life holding and continuing to hold the same as expressed in the Thirty-nine Articles interpreted in their plain and natural sense.” The Colonial and Continental Church Society, with which Hellmuth had been associated, also proved to be a friend to the college from the first. The accent on “Protestant and Evangelical principles” produced financial support in England which almost certainly would not otherwise have come. Cronyn applied to the legislature for a charter and on 5 May 1863 the act to incorporate Huron College received royal assent. The college opened on 2 December.

Such was the uncompromising theology of Cronyn that when he received an invitation from the archbishop of Canterbury to attend the first Lambeth Conference in September 1867, he viewed it with suspicion. The conference had developed from a suggestion of the provincial synod of Canada, that a “Pan-Anglican Conference of Bishops” be called to discuss common problems [see James Beaven]. One was the privy council decision of 1865 in the case of Bishop Colenso, which had put the validity of all documents appointing the bishops in self-governing colonies in doubt; another was the effect of the publication in 1860 of the theologically controversial Essays and reviews.

Cronyn gave his opinion of the proposed gathering in no uncertain terms in his charge to synod in 1867: “It is evident that his Grace intends that all should understand that the meeting is to be regarded merely as a social gathering. . . . Of course, all shades of opinion, recognised or not recognised in the church, would be represented there, from the almost full-blown Romanism of those who boldly profess to celebrate the mass in our churches, with incense and the idolatrous worship of the consecrated elements, to the feeble, timid and dishonest efforts of incipient innovators, who are endeavoring, bit by bit, to introduce the exploded and condemned ritual of former days, and thus in time to effect the unprotestantizing of our church, by accustoming the people to the ritualism of Rome, and thus undoing the work of the Reformation.” Nor was he alone in his opposition, for the archbishop of York and the dean of Westminster also would not cooperate.

The synod nevertheless requested Cronyn to attend the conference, which he did “with much diffidence and hesitation.” He was not unhappy over the proceedings, and on the invitation of the Colonial and Continental Church Society he preached “in the two English Churches” in Paris. He visited the Paris exhibition of that year and was surprised to find that the “circulation of God’s Holy Word, and of religious publications of various kinds” was being extensively carried on. He was not so happy with what he saw at St Alban’s, Holborn, London. He left that church humiliated and grieved, and more than ever convinced of the necessity of guarding against the introduction “even of the smallest things savouring of those superstitious observances which can hardly be distinguished from the ceremonial of the Church of Rome.”

While in England, Cronyn interviewed the secretary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, who told him that the society had decided to reduce its annual grant to the diocese from £1,200 to £800. The reduction meant that assistance to ten missionaries had been withdrawn. In order to make up the deficiency Cronyn suggested at the 1868 synod that a general appeal should be made throughout the diocese. The synod responded to the proposal by launching a “Sustentation Fund” appeal which by 1869 had reached nearly $30,000. Cronyn advocated making the fund sufficiently large to provide “a moderate endowment in the Diocese for all time to come,” as the voluntary system had never been found sufficient to supply the spiritual wants of the people; by 1871 the fund had reached $68,000. Cronyn had again shown his ability for fund raising, as he had in 1854.

A measure of Cronyn’s contribution to the diocese is provided by his report to his final synod in 1871. At that time there were 88 active clergymen and one superannuated. During the preceding year he had confirmed 1,371 candidates, preached 65 sermons, delivered 43 addresses to candidates, ordained seven priests and six deacons, consecrated six churches, opened two churches for divine worship, visited 67 congregations in ten counties, and travelled 3,355 miles.

Cronyn’s evangelical views, maintained by the early Irish clergy in the diocese and by the many who followed them, were sustained by the teaching at Huron College. They coloured the theology of the diocese of Huron for many years after his death. He must not, however, be judged by his theological views alone. His practical contributions were lasting and incalculable. The number of clergymen in the newly formed diocese had more than doubled by 1871. He had opened no fewer than 101 churches. Parishes in the same period increased in number from 39 to 160. Of the latter 15 were vacant, suggesting a need for perhaps an additional eight clergy. Huron College, the institution which Cronyn had founded on his own initiative, supplied over the years many clergy not only for his own diocese but for the Canadian church at large and the mission field. From Huron College, through the efforts of Hellmuth, grew the present University of Western Ontario, which became non-denominational in 1908.

Cronyn was pre-eminent as a judge and recruiter of men. Six of the clergy he ordained during his episcopate (they numbered at least 83) were destined to become bishops: in addition to the three volunteers he brought from Ireland following his consecration he ordained John McLean*, Maurice Scollard Baldwin*, and William Cyprian Pinkham. He was also a most indefatigable and successful raiser of funds. Philip Carrington was to say: “The new Diocese of Huron, under its energetic and forceful bishop, became a powerhouse for the whole Canadian Church. He was a great fighter, and a great fisher of men.”

[The only collection of Cronyn papers is in the library of Huron College, London, Ontario. It is a small collection of documents and letters dealing with the every-day life and business of four generations of the family. The synod office of the diocese of Huron possesses a Cronyn letter book, covering the period 1858–67, which deals with diocesan matters. The John Strachan papers and letter books at PAO contain material from Cronyn between 1840 and 1865. Cronyn was a prolific pamphleteer, and his addresses to synod, although not always printed, give his views and describe his activities in great detail. j.j.t.]

Benjamin Cronyn, The bishop of Huron to the clerical and lay gentlemen composing the Executive Committee of the Synod of the Diocese of Huron (n.p., 1860); [ ], Bishop of Huron’s objections to the theological teaching of Trinity College, as now set forth in the letters of Provost Whitaker . . . (London, C.W., 1862); A charge delivered to the clergy of the Diocese of Huron, in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, Canada West, at his primary visitation, in June, 1859 (Toronto, 1859).

The bishop of Huron and Trinity College, Toronto ([London, C.W., 1860]). The bishop of Huron’s objections to the theological teaching of Trinity College, with the provost’s reply (Toronto, 1862). James Bovell, Defence of doctrinal statements; addressed to the right rev. the lord bishop of Toronto, the right rev. the lord bishop of Huron, and the Corporation of Trinity College . . . (Toronto, 1860). The episcopal controversy; being a series of letters written by the respective friends of the Ven. Archdeacon Bethune, D.D., and Dr. Cronyn, rector of London; the two candidates for the bishopric of the western diocese (London, C.W., 1857). The gospel in Canada: and its relation to Huron College . . . (London, C.W., [1865?]). The judgments of the Canadian bishops, on the documents submitted to them by the Corporation of Trinity College, in relation to the theological teaching of the college (Toronto, 1863). [J. T. Lewis], A letter to the right rev. the lord bishop of Huron by the lord bishop of Ontario ([n.p., n.d). [A Presbyter], Strictures on the two letters of Provost Whitaker in answer to charges brought by the lord bishop of Huron against the teaching of Trinity College (London, C.W., 1861). The protest of the minority of the Corporation of Trinity College, against the resolution approving of the theological teaching of that institution (London, C.W., 1864). Adam Townley, A letter to the lord bishop of Huron: in personal vindication; and on the expediency of a new diocesan college (Brantford, C.W., 1862). George Whitaker, Two letters to the lord bishop of Toronto, in reply to charges brought by the lord bishop of Huron against the theological teaching of Trinity College, Toronto (Toronto, 1860). Church of England, Synod of the Diocese of Huron, Minutes, 1858–71 (London, Ont., 1862–71). London Free Press, 8–10 July 1857, 23 Sept. 1871. Upper Canada, House of Assembly, Appendix to journal, 1836, app.106, p.60. R. T. Appleyard, “The origins of Huron College in relation to the religious questions of the period,” unpublished ma thesis, University of Western Ontario, 1937. A. H. Crowfoot, Benjamin Cronyn, first bishop of Huron (London, Ont., 1957). C. H. Mockridge, The bishops of the Church of England in Canada and Newfoundland . . . (Toronto, 1896), 150–62. J. J. Talman, Huron College, 1863–1963 (London, Ont., 1963) J. J. and R. D. Talman, “Western” – 1878–1953 (London, Ont., 1953). Verschoyle Cronyn, “The first bishop of Huron,” London and Middlesex Hist. Soc., Trans., III (1911), 53–62. S. W. Horrall, “The clergy and the election of Bishop Cronyn,” Ont. Hist., LVIII (1966), 205–20.

Cite This Article

James J. Talman, “CRONYN, BENJAMIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cronyn_benjamin_10E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cronyn_benjamin_10E.html |

| Author of Article: | James J. Talman |

| Title of Article: | CRONYN, BENJAMIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1972 |

| Year of revision: | 1972 |

| Access Date: | December 13, 2025 |