Source: Link

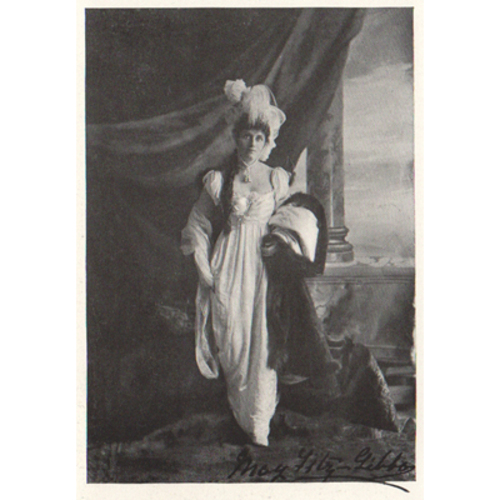

BERNARD, MARY (May) AGNES (FitzGibbon), known as Lally Bernard, journalist and hostel manager; b. probably in 1862 in Barrie, Upper Canada, daughter of Richard Barrett Bernard, a barrister, and Agnes Elizabeth Lally; m. 13 Aug. 1882 Clare Valentine FitzGibbon (1858–1919) in Marblehead, Mass., and they had a daughter; d. 17 July 1933 in Victoria.

Mary Agnes FitzGibbon never intended to become a journalist. She belonged to Canada’s elite: her aunt Susan Agnes Bernard* married Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald*; her uncle Hewitt Bernard* was an important civil servant; and her stepfather, D’Alton McCarthy*, was a lawyer and Liberal-Conservative mp. Mary was privately educated and introduced into high society in Ottawa and London, England. In 1882 she married Clare Valentine FitzGibbon, grandson of the 3rd Earl of Clare, an Irish landlord. Mary reportedly lived abroad with her husband for several years, after which he was confined to an asylum. Biographies of Mary FitzGibbon written in her lifetime do not mention her husband’s situation, perhaps because of the stigma attached to mental illness [see Charles Kirk Clarke*]. In Canadian men and women of the time (1912), Henry James Morgan* states that Mary had “made her permanent home with her step-father” in 1896, but Clare’s institutionalization may have taken place earlier: he does not appear alongside his family in the 1891 census, which shows that Mary and their only child, Agnes Florence Frances Louise, were then living with D’Alton and Agnes McCarthy in Toronto.

After her stepfather died as the result of a carriage accident in 1898, FitzGibbon became the main supporter of her invalid mother and her daughter. Mary thus turned to journalism out of necessity. The following year she wrote landmark articles for John Stephen Willison*’s Toronto Globe on the Doukhobors, a misunderstood immigrant group [see Peter Vasil’evich Verigin*]. She had become part of their community for three months, trailing them from immigration sheds in Winnipeg to settlements where they erected homes that, as she put it, “would have done credit to a skilled master-builder.” By telling readers the story of a people who were seeking refuge in Canada “to prevent their extermination in the hands of the Russian authorities,” she hoped to dispel the myth that the Doukhobors were “taking the land … destined for our grandchildren.” On the contrary, their homesteads were “not more than a mere ‘postage stamp flung on a tablecloth of large dimensions.’” She conceded that their desire to be exempted from serving in the armed forces might be incomprehensible to Canadians, but noted that the term “military service” carried a different meaning for the Doukhobors, who were horrified by the brutality of the Russian army. “That these people did not tolerate the life mapped out for them by the military authorities of Russia,” she argued, “is, perhaps, the greatest of all reasons why they are fit people to become citizens of a country such as ours.”

FitzGibbon’s articles on the Doukhobors, which demonstrated great reporting skill and literary promise, are likely what earned her a permanent position at the Globe, where she wrote a regular column entitled “Driftwood.” Like Kit Coleman [Ferguson*], whose “Woman’s kingdom” was featured in the Toronto Daily Mail and Empire, FitzGibbon was interested in topics beyond those, such as housekeeping and fashion, that filled typical women’s pages. “Driftwood” focused on social and cultural affairs. She took a special interest in the arts, both as a supporter of Canadian talent and as a discerning critic. On 4 March 1902, in a review of the annual exhibition of the Ontario Society of Artists, she wrote, “Truly this is Canada’s ‘growing time’ in matters artistic.… We can hardly boast that we have as yet in this country an art centre.” The void, she noted, must leave most artists with “a sense of intense loneliness” as they laboured in isolation and then, after showing their work, had to “bear the keen criticism of the few trained to detect faults rather than merits.”

Shortly after covering the coronation of King Edward VII in August 1902, FitzGibbon became the London correspondent for the Globe, the Manitoba Free Press, owned by Clifford Sifton* and edited by John Wesley Dafoe*, and the Toronto Evening News, which was edited by Willison from January 1903. While living in England, FitzGibbon, who had been a member of the Imperial Federation League in Toronto [see George Taylor Denison*], gave speeches under the auspices of the Victoria League and the Tariff Reform League, both of which promoted closer relations between Great Britain and its colonies. In 1916 writer Ethel Cody Stoddard would praise her in a Canadian Magazine article for using “platform and pen” to advocate imperial unity.

FitzGibbon was an energetic promoter of women’s causes. She attended the 1903 convention of the National Council of Women of Canada in Victoria, and she was an active member of the Vancouver chapter of the Canadian Women’s Press Club. She was, however, firmly anti-suffrage, a stance that may have been influenced by her editors, who believed that their readers did not want women to have the vote. Her views on the subject appear to have softened over time. In January 1918, while living in Victoria, she was elected the first president of the League for Good Government, an umbrella organization for several women’s groups. That month she was asked why the league was backing First World War veteran Walter Drinnan in a provincial by-election rather than his opponent, Mary Ellen Smith [Spear], the widow of politician Ralph Smith*. FitzGibbon replied, “While the organization is anything but opposed to women having direct representation in the provincial parliament we feel that this is not the psychological moment, that the soldier citizen is the ideal representative at such a period.” Local voters thought otherwise: Smith, whose slogan was “Women and children first,” won with a majority of 3,500.

Throughout her career in journalism, FitzGibbon kept a careful separation of her public and private lives. Scholar Marjory Lang notes that when readers wrote to her seeking personal advice, FitzGibbon preferred not to share her own stories with them or respond directly to their queries, and instead “used their various plights as vehicles for discourse on general social ills.” In her “Driftwood” column of 7 May 1904, for example, she lamented: “We women are brought up in an atmosphere which compels us to suppress any original ideas.… There is so much repression, so much ‘Don’t, dear,’ when we are small, and so many attempts to mould us in exactly the same groove as our ancestresses, that we get little chance of thinking and giving utterance to those thoughts in a manner which would interest the public.” FitzGibbon maintained the persona of a “well-educated, well-to-do gentlewoman,” in Lang’s words, but privately she struggled to make a living and “constantly teetered on the edge of insolvency.” In her column of 7 May 1904 she remarks that London’s women journalists have the “worn, ‘driven’ look that seems to come with the ceaseless work and worry of their occupation.”

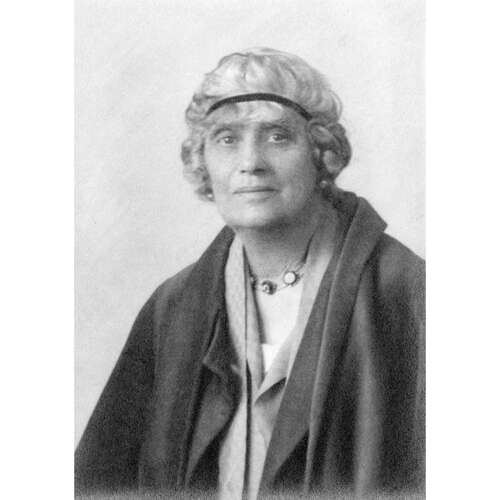

FitzGibbon returned to Canada in 1907 and settled in Victoria, where she occasionally wrote travel pieces on “Canada’s Riviera” for publications in England. She also avidly pursued an idea she had come to cherish as she grew sensitized to the plight of immigrants, about which she had written for her first assignment as a journalist, especially immigrant women. She approached Lord Strathcona [Smith*], a Scottish-born railway titan and legendary philanthropist, with a plan to found a hostel where young British women could, for a small fee, live in a temperate climate and learn to become “competent housewives” who could perform domestic tasks along “good, practical, homespun lines.” Lord Strathcona agreed to underwrite the project, and in 1912 he set up a $100,000 trust fund that was used to purchase a large house at 2412 Alder Street in Vancouver. Lady Minto [Grey] was the patron, and Queen Mary asked that the venture be named in honour of her coronation in 1911. The opening of Queen Mary’s Coronation Hostel in 1913 was the realization of a dream for FitzGibbon. “This hostel,” Stoddard observed, “… is the only one of its kind in the world, a fact which shows that the Lally Bernard individuality has by no means evaporated with the years.”

Mary Agnes FitzGibbon’s strong attachment to Britain, forged from years of living in England and frequent return visits, had imbued her with a fervent desire to strengthen imperial ties through her work with the hostel. She headed its board of management, which oversaw day-to-day operations, until her death in 1933. She handled the selection and admittance of each guest, arranging for the immigration of gentlewomen who possessed, in her view, good breeding, manners, culture, and refinement. By assisting these women, FitzGibbon was able to once again champion newcomers to Canada, as she had done many years earlier with her groundbreaking reports on the Doukhobors.

Mary Agnes Bernard FitzGibbon, writing as Lally Bernard, is the author of newspaper articles that were published as The Canadian Doukhobor settlements: a series of letters (Toronto, 1899), and she wrote frequently for the Toronto Globe and Evening News as well as the Manitoba Free Press. The City of Vancouver Arch. holds a digitized photograph of Bernard (AM54S4-2-CVA 371-1601) at searcharchives.vancouver.ca/mrs-clare-fitz-gibbon-founder-of-queen-mary-coronation-hostel;rad.

Mary Agnes Bernard FitzGibbon is sometimes confused with Mary Agnes FitzGibbon (1815–1915), the author of A trip to Manitoba; or, roughing it on the line (Toronto, 1880) and granddaughter of Susanna Moodie [Strickland*]. Biographies of both can be found in A. I. Dagg, The feminine gaze: a Canadian compendium of non-fiction women authors and their books, 1836–1945 (Waterloo, Ont., 2001).

BCA, GR-2951, no.1933-09-484181. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Massachusetts marriages, 1841–1915”: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NW1N-VRS (consulted 26 Feb. 2020). City of Vancouver Arch., AM55 (Queen Mary’s Coronation Hostel fonds). LAC, R233-36-4, Ont., dist. Toronto (119), subdist. St Patrick Ward (G), div. 3: 17; R233-37-6, Ont., dist. Toronto West (118), subdist. Ward 4 (B), div. 30: 17. Globe, 4 March 1902, 7 May 1904. Vancouver Courier, 22 Jan. 2015. Vancouver Daily World, 17 Jan. 1918. A flannel shirt and liberty: British emigrant gentlewomen in the Canadian west, 1880–1914, ed. Susan Jackel (Vancouver, 1982). M. L. Lang, Women who made the news: female journalists in Canada, 1880–1945 (Montreal and Kingston, Ont., 1999). E. C. Stoddard, “An imperial daughter,” Canadian Magazine, 46 (November 1915–April 1916): 513–15. Types of Canadian women …, ed. H. J. Morgan (Toronto, 1903).

Cite This Article

Linda Kay, “BERNARD, MARY (May) AGNES (FitzGibbon), known as Lally Bernard,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bernard_mary_agnes_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bernard_mary_agnes_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Linda Kay |

| Title of Article: | BERNARD, MARY (May) AGNES (FitzGibbon), known as Lally Bernard |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2023 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | March 1, 2026 |