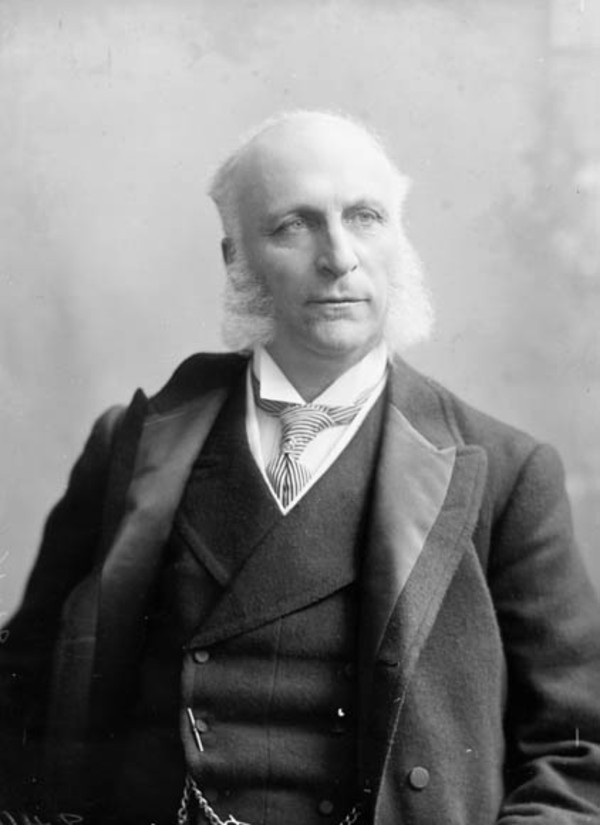

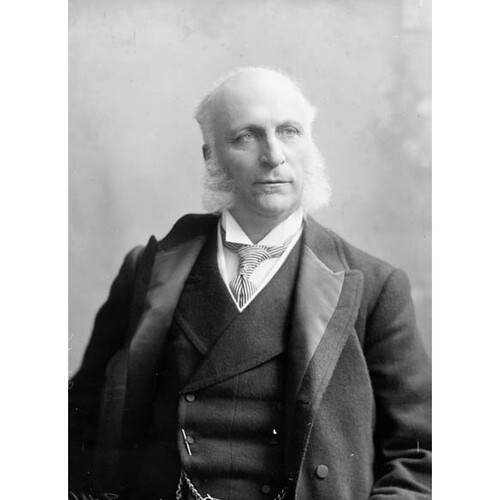

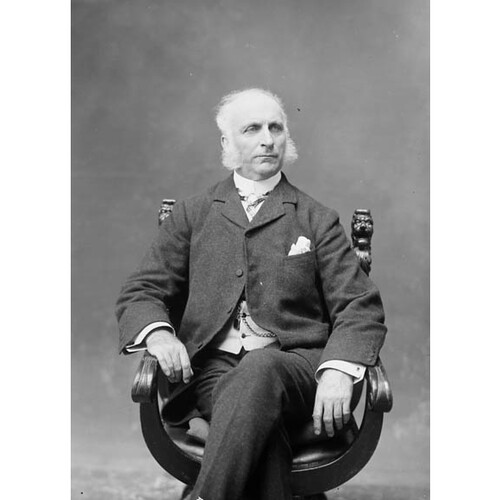

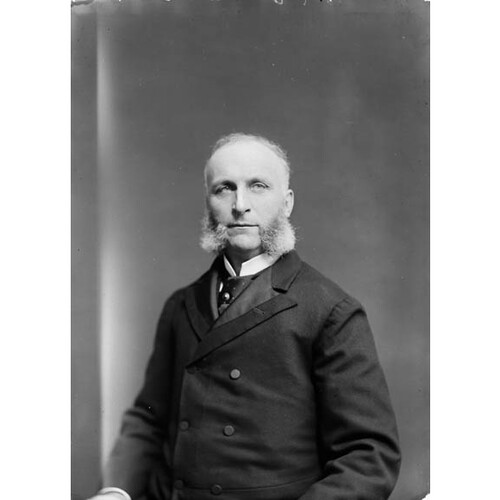

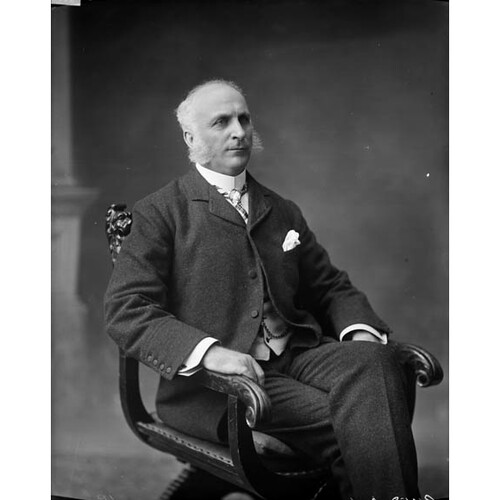

BORDEN, Sir FREDERICK WILLIAM, physician, businessman, militia officer, and politician; b. 14 May 1847 in Upper Canard, N.S., only son of Dr Jonathan Borden and Maria Frances Brown; m. first 1 Oct. 1873 Julia Maude Clarke (d. 1880) in Canning, N.S., and they had two daughters and a son; m. there secondly 12 June 1884 Julia’s sister, Bessie Blanche Clarke; d. there 6 Jan. 1917.

The son of a popular, public-spirited physician of Planter origin, F. W. Borden was educated at Acacia Villa School in Lower Horton, N.S., King’s College in Windsor (ba 1866), and Harvard Medical School in Boston (md 1868). Upon his return to Nova Scotia, he practised medicine in Canning, a thriving inland port and market town of some 600 people. To supplement his income (there were four other physicians in Canning) he invested in ships and local utilities, bought and sold real estate, and served as an agent, first of the Bank of Nova Scotia (1882–91) and then of the Halifax Banking Company (1891–96). By 1897 he owned two 125-to-150-ton vessels and the controlling interest in a third. On the land he planted orchards, grew wheat, hay, potatoes, and cranberries, and established a 150-acre livestock farm at Pereau, a lumbering business at Gaspereau and Blomidon, and general stores in Canning and Blomidon. He also invested in the Cornwallis Valley Railway Company Limited, the Canning Water and Electric Light, Heating and Power Company Limited, the Western Chronicle (Kentville), and other local enterprises.

In October 1895 the greater part of Borden’s assets were incorporated as the F. W. Borden Company Limited, with an initial stock of $50,000, later increased to $250,000. Incorporation gave the company broad powers to own, sell, and develop farm and other properties, lumber operations, and electrical, transportation, and communications facilities. Following his admission to the federal cabinet in 1896, the company’s name was changed to the R. W. Kinsman Company Limited, after its executive director, and then in 1901 to the Nova Scotia Produce and Supply Company Limited, with a capital stock of $500,000. Two years later the firm’s title was reduced to the Supply Company Limited, and its capitalization to $200,000.

While the company’s reduced capitalization may have resulted from a more realistic assessment of assets, it may also have represented a new entrepreneurial strategy, since after 1903 Borden formed several other companies to exploit the more specific powers of the original firm, often to gain entry into larger enterprises, and frequently in tandem with outside entrepreneurs. Although the core of his profitable assets appears to have remained in regional enterprises, he held shares in some 75 or more other companies elsewhere in Canada and in the United States and Cuba, with interests in insurance, banking, mining, farming, real estate, resources, and utilities.

Although at his death Borden’s wealth was estimated at $300,000, for years his annual income had supported an expensive personal and public life. A Liberal Reformer from a prominent political family, he had resided in Canning less than four years when he unseated the parliamentary incumbent in the federal constituency of Kings in 1874. He held this seat for the Liberals until 1911, except for 1882–87. As the economy and people of Kings shifted from the coast, the heart of his political support, inland to its towns, the stronghold of his opponents, Borden adjusted his rhetoric and policies. From the opposition benches he espoused reciprocity, denounced the inefficiency and partisanship of the Intercolonial Railway, championed the Windsor and Annapolis Railway which ran through his constituency, though it was owned and operated by his political opponents, and made every effort to secure public works for Kings, particularly in the county’s growing towns.

Under Wilfrid Laurier, who became the federal Liberal leader in 1887 and with whom Borden developed a close personal friendship, Borden assumed an increasingly important role in the party. In 1890 he was one of the founders of the Nova Scotia Liberal Association, which he served as vice-president, and the following year he became his province’s Liberal spokesman in the House of Commons. In 1893 he helped organize the national Liberal convention, where he presided at the meeting which organized the Maritime Liberal Association; the association named him and William Stevens Fielding*, the premier of Nova Scotia, the province’s representatives on its executive. In the commons in 1894 Borden delivered a stinging arraignment of the crumbling Conservative administration’s manipulation of the 1891 census return for his constituency, an attack that produced a major sensation and led the government to close the files to further investigation. His growing stature in national politics was similarly revealed in his forthright condemnation of the Conservatives’ Manitoba school policy [see Sir Mackenzie Bowell]. Later published in pamphlet form during the 1896 general election, it was dubbed “the Nova Scotian interpretation of the remedial bill.”

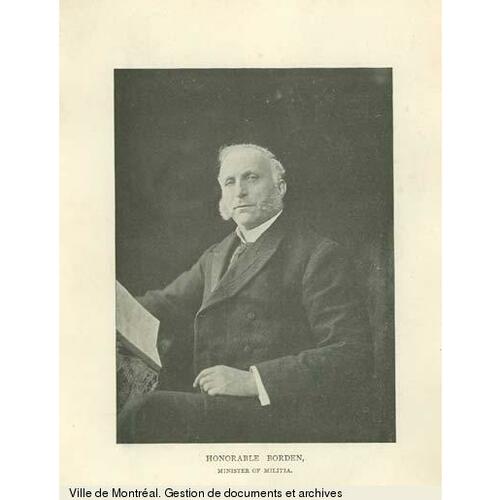

Borden’s political durability, urbanity, geniality, and organizational skills made him an obvious candidate for Laurier’s first cabinet in 1896. His long service in the militia, which he had joined first as a cadet at King’s College and then in 1869 as an assistant surgeon in the 68th (Kings) Battalion of Infantry, his membership in the parliamentary militia lobby, and his continued participation in summer militia camp at Aldershot, N.S., made him an even more logical choice for the Department of Militia and Defence. During his record 15 years in this post Canada sent some 200 troops in 1898 to help the hard-pressed North-West Mounted Police maintain order in the Yukon gold-fields, and between 1899 and 1902 dispatched 7,300 men to assist the British in the South African War. While an active advocate of Canadian participation in this conflict, he insisted that Canadian units be kept together rather than distributed among British units, and he employed the war to test mobilization, organization, and equipment. Subsequently, he used the returned soldiers’ experience and the public’s enthusiasm to assist in the reform of the militia. During his administration, often seen as the end of the long period of “cool indifference” toward the militia, the departmental estimates tripled and the force was reformed, reorganized, and re-equipped.

From the start Borden insisted on an annual drill of the militia, for training had become haphazard and in some years had been dropped altogether. He also began a general housecleaning of the headquarters staff. During his first year and a half he abolished some positions, combined others, and replaced civilians with serving officers. In the next few years examinations were required for promotion to senior posts, schools of instruction were established, the Royal Military College of Canada was reformed, senior officers were sent to Britain for advanced training, and the skeleton of a general staff was created. He increased pay and retirement benefits, established rules regulating tenure of command, decentralized command and administration, and equipped the militia with modern weapons. In 1905 he acquired a large central training base near Petawawa, Ont., and in 1909 it was from this base that John Alexander Douglas McCurdy* undertook, on his authorization, the first military test flight of an airplane in Canada.

Borden’s larger aim was to create a self-contained citizen army and to win a greater degree of autonomy within the imperial defence system. To meet the prevailing criticism that the Canadian militia was little more than a glorified police force, its fighting arms devoid of the service corps necessary to transport, clothe, feed, munition, and care for a field force, Borden created a medical corps, an army service corps, and an ordnance corps, as well as a corps of engineers, a corps of guides, a corps of signals, and a pay corps. After a close look at various national military systems, particularly the Swiss, Borden announced a somewhat grand plan to train a vast army of 100,000 citizen sharpshooters, which would constitute Canada’s low-cost, first line of defence. These sharpshooters would be given a minimal training at summer camps by the small Permanent Force, and during the rest of the year they would hone their skills at government-constructed rifle ranges across the country.

To extend Canadian military autonomy Borden amended the Militia Act in 1904 to permit Canadian officers to accede to the office of general officer commanding the militia, hitherto reserved by Canadian law for an officer in the British army; the same act abolished the provision that the command of the militia in wartime should fall to the officer commanding British troops in Halifax. Earlier he had alarmed British officers serving in the Canadian militia by insisting that their seniority be based on the date of their Canadian rather than their British commission, a reform that was enshrined in the new act. The first colonial statesman invited to participate in the Committee of Imperial Defence, Borden had agreed at a meeting in December 1903 to take control of the British garrisons at Halifax and Esquimalt, B.C., a gesture hailed by one Liberal journal as another “long, though unostentatious step, in the direction of complete Canadian nationhood.” Similarly, he insisted upon creating a Canadian general staff rather than agree to the imperial government’s pleas for an integrated imperial staff. His decision in 1902 to replace the Lee-Enfield rifle with a Canadian weapon, the famous Ross rifle, proved less successful; though it remained an excellent target rifle, it was to fail miserably in the test of battle.

If Borden worked to further Canadian autonomy, he nevertheless remained committed to collaboration in imperial defence. His enthusiasm for Canada’s participation in the South African War, and after the war his support for linking British and Canadian regiments, his dispatch of senior officers for training in Britain, his continued use of selected British officers for training the Canadian militia, and his acceptance of a plan for the dispatch of Canadian troops overseas demonstrate his positive, cooperative rather than integrative, approach to imperial defence.

Several controversies troubled Borden’s public career; two entailed the dismissal of general officers commanding the Canadian militia. In January 1900 the Laurier government demanded the removal of Major-General Edward Thomas Henry Hutton*, with whom Borden had differed on matters of policy and administration, for insubordination. A constitutional crisis was narrowly avoided when the Colonial Office refused to support the resistance of the governor general, Lord Minto [Elliot], and instructed the War Office to recall Hutton immediately. In 1904 when Lord Dundonald [Cochrane*], the general officer commanding, who had failed in his efforts to sabotage the revision of the Militia Act, publicly accused Borden’s temporary deputy, Sydney Arthur Fisher*, the minister of agriculture, of patronage, the Laurier government demanded Dundonald’s removal as well, and the governor general made little effort to resist. The controversy convinced Borden of the need to create a militia council, a proposal borrowed from the War Office’s reconstruction committee and designed to strengthen civilian control over the military. The council, composed of three civilians and four military officers, served as a forum for the exchange of information and opinion, provided continuity, and placed the minister, who chaired it, in full charge of his department.

Another political controversy entailed charges that Borden had knowingly procured a fraudulent concentrated food powder for emergency use by Canada’s second contingent of troops for South Africa, thereby endangering their lives. The product had been developed by the Hatch Protose Company of Montreal and sold to the militia department by the company’s former agent, Dr Francis Eugene Devlin, a friend of the government who had set up his own company to produce the food powder. Although in June 1900 the majority report of a parliamentary committee investigating the charges exonerated both Devlin and the minister, it is clear that Devlin had delivered a faulty product and had deceived John Louis Hubert Neilson, the militia department’s director general of medical services, whom Borden had asked to test the product. The Conservatives had hoped to give this issue a large place in the khaki election of November 1900, but 18 days after the committee’s report news of the death in battle of the minister’s only son, Harold Lothrop*, triggered an outburst of public sympathy which countered much of the opposition’s criticism.

Two other controversies were more personal. The first centred on the New Brunswick Cold Storage Company Limited’s receipt in 1907 of a large subsidy from the Department of Agriculture, and similar subsidies and benefits from the provincial and municipal governments and the Intercolonial Railway. Although the company was administered by one of Borden’s sons-in-law, Borden was its principal shareholder; he was also a close personal friend of the minister of agriculture. As a result of the public exposure he reluctantly divested himself of his interests, at least formally.

The second personal controversy surfaced during the 1908 election in which he was opposed by a coalition of Conservatives and moral reformers operating under the name Union Reformers. They attacked him on patronage and on his alleged marital infidelities and overfondness for alcohol during an electoral contest which received national coverage but which he had no difficulty winning. The highlight of the local campaign came when Borden charged an opponent, William M. Carruthers, with criminal libel for distributing copies of the Calgary Eye Opener recounting his supposed liaison with a Montreal woman, a tale which had circulated privately for 13 years. A lengthy and highly publicized jury trial ended with a unanimous decision and Carruthers was fined. The Nineteenth Century and After (London), which had run a similar article, settled out of court.

By this time Borden had become a prominent public figure in Canada and abroad. Created a kcmg in June 1902, he attended the coronation of Edward VII, dined with the king and queen in 1907, attended the coronation of George V, was made a knight of grace of the Order of St John of Jerusalem in England, was named an honorary surgeon-general of the British army, received a dcl at King’s College and a lld at the University of New Brunswick, served as president of the Strathcona Trust and as vice-president of the British Empire League and the Imperial Commercial Club, and was director of the Home Scholarship Fund. Known as a bon vivant, he belonged to at least 20 private clubs and travelled widely. He also generously supported a large number of religious, educational, patriotic, and charitable organizations. He and Lady Borden (regal, sociable, and active in good works) dispensed their legendary hospitality from two residences, Stadacona Hall in Ottawa, the large stone house formerly occupied by Sir John A. Macdonald* and Lady Macdonald [Bernard], and Borden Place, a spacious wooden home in Canning, constructed in Queen-Anne Revival style and served with a rail spur for the ministerial coach. Twice he was offered the lieutenant governorship of Nova Scotia, but he declined for the promise of the high commissionership in London, an appointment which Laurier announced publicly at a banquet in London on 30 June 1911. Before Lord Strathcona [Smith] could resign, however, a federal election was called, and Borden’s and the Laurier government’s defeat deprived him of that post. Although he was out of office at the time, the Canadian army base created in Ontario in 1916 was named Camp Borden in his honour.

His death in January 1917, after only a few days of illness, while he was still active in politics and ready to enter the next election, ended a long and distinguished career of public service. A versatile regional entrepreneur, a durable and skilful politician, Borden was considered by some of his contemporaries, including members of the opposition, to have been the best minister of militia to date; in the words of the British military magazine the Broad Arrow in 1901: “No Minister of Militia has ever done so much toward making the Canadian forces so thoroughly effective and ready for the field as he,” an assessment with which contemporary historians would concur.

British Library (London), Add.

Cite This Article

Carman Miller, “BORDEN, Sir FREDERICK WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 28, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/borden_frederick_william_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/borden_frederick_william_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carman Miller |

| Title of Article: | BORDEN, Sir FREDERICK WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | February 28, 2026 |